Treatment of Resistant Depression in Adolescents (TORDIA): Week 24 Outcomes

Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this study was to report on the outcome of participants in the Treatment of Resistant Depression in Adolescents (TORDIA) trial after 24 weeks of treatment, including remission and relapse rates and predictors of treatment outcome.

Method

Adolescents (ages 12–18 years) with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI)-resistant depression were randomly assigned to either a medication switch alone (alternate SSRI or venlafaxine) or a medication switch plus cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT). At week 12, responders could continue in their assigned treatment arm and nonresponders received open treatment (medication and/or CBT) for 12 more weeks (24 weeks total). The primary outcomes were remission and relapse, defined by the Adolescent Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation as rated by an independent evaluator.

Results

Of 334 adolescents enrolled in the study, 38.9% achieved remission by 24 weeks, and initial treatment assignment did not affect rates of remission. Likelihood of remission was much higher (61.6% versus 18.3%) and time to remission was much faster among those who had already demonstrated clinical response by week 12. Remission was also higher among those with lower baseline depression, hopelessness, and self-reported anxiety. At week 12, lower depression, hopelessness, anxiety, suicidal ideation, family conflict, and absence of comorbid dysthymia, anxiety, and drug/alcohol use and impairment also predicted remission. Of those who responded by week 12, 19.6% had a relapse of depression by week 24.

Conclusions

Continued treatment for depression among treatment-resistant adolescents results in remission in approximately one-third of patients, similar to adults. Eventual remission is evident within the first 6 weeks in many, suggesting that earlier intervention among nonresponders could be important.

Approximately 60% of adolescents with major depressive disorder will respond to initial treatment with either an antidepressant medication or an empirically validated method of psychotherapy, and a similar proportion of treatment-naive depressed adolescents will attain symptomatic remission after 6 months of treatment (1, 2). Less is known about the longer-term outcomes of adolescents with treatment-resistant depression.

The Treatment of Resistant Depression in Adolescents (TORDIA) study (3) was a six-site study designed to examine second-step interventions in adolescents with depression who had not responded to an initial selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) trial. Participants were randomly assigned to one of the following four treatments: 1) switch to another SSRI; 2) switch to venlafaxine; 3) switch to another SSRI plus cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT); or 4) switch to venlafaxine plus CBT. As reported previously, during the first 12-week acute phase of the study, 47.6% of participants responded to treatment, with greater response to medication switch plus CBT (54.8%) than to medication switch alone (40.5%) but no difference in the response rate between the two medication switch strategies (3). The longer-term goal of the treatment of depression is not just response but the achievement of the absence of symptoms, or remission. Therefore, in the present study we report on the outcome of participants in the TORDIA study after 24 weeks of treatment and address the following hypotheses:

1. Remission will be more likely among those treated with CBT and among those who received venlafaxine, rather than an SSRI;

2. Among those who responded at 12 weeks, relapse will be less likely to occur among those treated with CBT or venlafaxine;

3. Remission will be more likely in those who responded by 12 weeks; and

4. Both remission and relapse will be predicted by baseline and week-12 levels of depression, suicidal ideation, hopelessness, drug and alcohol use, anxiety, and family conflict.

We also examine the impact of the most common open treatments (e.g., addition of psychotherapy, augmentation with a mood stabilizer, and switch to another antidepressant) on those who did not respond to their assigned treatment.

Method

The TORDIA study was a six-site randomized, controlled trial using a 2×2 balanced factorial design. We have previously reported on methods, treatment efficacy, predictors and moderators of response, and suicidal events for the first 12 weeks of treatment (3–5).

Participants

Participants were 334 adolescents (ages 12–18 years) with DSM-IV major depressive disorder or dysthymia (6) that persisted despite treatment with an SSRI for at least 8 weeks, the last four of which were at a dosage equivalent of at least 40 mg of fluoxetine. Participants were of mid-adolescent age (mean age=15.9 years [SD=1.6]), mostly girls (N=233 [69.8%]), and mostly Caucasian (N=277 [82.9%]).

Individuals were excluded if they had two or more adequate trials of an SSRI or a history of nonresponse to venlafaxine (≥4 weeks at a dosage of ≥150 mg) or CBT (≥7 sessions). Those taking antipsychotics, mood stabilizers, or non-SSRI antidepressants were excluded, with the exception of individuals receiving stable doses (≥12 weeks duration) of stimulants, hypnotics (trazodone, zolpidem, zaleplon), or anti-anxiety agents (clonazepam, lorazepam). Diagnoses of bipolar spectrum disorder, psychosis, pervasive developmental disorder or autism, eating disorders, substance abuse or dependence, or hypertension (diastolic blood pressure ≥90) were also exclusionary (3).

The study was approved by each site's local institutional review board. All participants and their parents gave written informed assent and consent in accordance with local institutional review board regulations.

Study Design

Participants were initially randomly assigned to one of the four aforementioned treatment groups. Randomization was balanced within and across sites on comorbid anxiety, depression duration ≥2 years, and suicidal ideation. CBT consisted of 12 weekly sessions followed by up to six booster sessions over the next 12 weeks, using techniques of behavior activation, cognitive restructuring, problem solving, and emotion regulation (3, 7). Participants, clinicians, and independent evaluators were blind to medication type. Independent evaluators were also blind to CBT assignment. For the first 181 participants, the SSRI options were fluoxetine and paroxetine. As a result of concerns about the safety and efficacy of paroxetine, citalopram was substituted for the remaining 153 individuals. Individuals who had previously failed a trial of fluoxetine were randomly assigned to receive paroxetine/citalopram or venlafaxine. Participants who had failed a trial of paroxetine/citalopram were randomly assigned to receive fluoxetine or venlafaxine. Those who had failed a trial of sertraline or fluvoxamine were randomly assigned to receive either of the two SSRIs (fluoxetine or paroxetine/citalopram) or venlafaxine.

Acute treatment

The dosage schedule for SSRIs was 10 mg at week 1 and 20 mg for weeks 2–6. The doses for venlafaxine at weeks 1, 2, 3, and 4–6 were 37.5 mg, 75 mg, 112.5 mg, and 150 mg, respectively. At week 6, the dosage for nonresponders (defined as a Clinical Global Impression (CGI) improvement rating ≥3) could be increased to 40 mg and 225 mg in the SSRI and venlafaxine cells, respectively. Dosing could be decreased if intolerable side effects were experienced. By week 12, the mean SSRI dose was 33.8 mg (SD=9.3), with no differences among the three SSRIs. The mean dose of venlafaxine was 205.4 mg (SD=33.1).

Treatment during weeks 13–24. Following the initial 12 weeks, responders remained in the same blinded treatment arm for an additional 12 weeks. Medication visits were monthly. CBT visits were every other week for 2 months and monthly thereafter. Those assigned to CBT received a mean of 2.8 sessions (SD=2.8 [range=0–10]). At week 12, nonresponders (CGI improvement rating ≥3 at week 12) and responders requiring additional nonstudy interventions (e.g., therapy, additional medications) were unblinded and entered into open treatment. Open treatment was not controlled and could consist of a switch to another antidepressant, augmentation, or the addition of CBT or other psychotherapy. Participants who were not already receiving the maximum dose could have the antidepressant dose increased during open treatment, although a dose increase alone was not cause for unblinding during weeks 12–24.

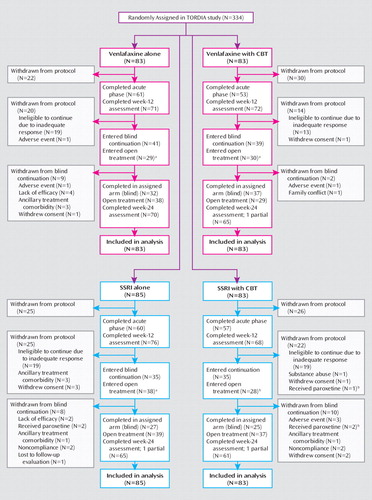

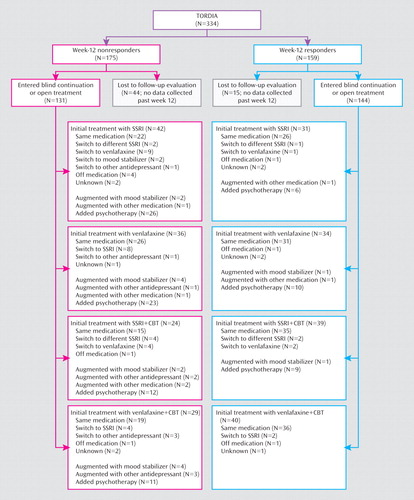

Of the 334 individuals enrolled in the trial, 78.1% (N=261) completed the week-24 assessment (an additional three individuals had partial week-24 assessments), with similar proportions in each treatment group (Figure 1). Those who were retained for the 24-week assessment were more likely to have been responders at week 12 (N=140/261 [53.6%] versus N=19/73 [26.0%], χ2=–17.44, df=1, p<0.001), but otherwise those who were lost to follow-up assessment and those who were retained were similar. More than one-half of the participants continued to receive their initial study medication throughout the 24 weeks (venlafaxine: N=112/166 [67.5%]; SSRI: N=99/168 [58.9%]), but because some received auxiliary treatments, only 41.6% (N=69/166) of those treated with venlafaxine and 31.0% (N=52/168) of those treated with an SSRI remained blinded. Because of the concerns about paroxetine, our Data Safety Monitoring Board directed us to unblind and remove from the study the eight participants in the SSRI cells assigned to receive paroxetine. Figure 2 describes the treatments received by participants during the course of the study by initial assigned treatment. Of those who were initially randomly assigned to receive medication without CBT, a total of 68/168 (40.5%) subsequently received psychotherapy (usually CBT), and 40/166 (24.1%) of those assigned to receive CBT also received some other form of therapy (e.g., family therapy).

aData include participants withdrawn from the study either before or after the end of the acute phase.

bData indicate that participants were taking paroxetine at the time of the 2003 United Kingdom report concerning paroxetine use, were unblinded, and were tapered off the medication.

Assessments

Clinical assessment

All participants, regardless of treatment status, were evaluated by an independent evaluator who was blind to treatment assignment at weeks 0, 6, 12, and 24. Initial and week-12 diagnoses were based on the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children–Present and Lifetime version criteria (8). Severity of depression at baseline and weeks 6, 12, and 24 was assessed using the Children's Depression Rating Scale–Revised (9). Clinical severity and improvement were assessed using CGI ratings (10). The Children's Depression Rating Scale–Revised and CGI assessments encompassed the previous 2-week period. Functional status was rated using the Children's Global Assessment Scale (11). At weeks 12 and 24, the independent evaluator also rated the week-by-week severity of depressive disorder for the previous 3-month period with the Adolescent Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation (12), using a 4-point scale (1=not present; 2=possible; 3=probable; 4=definite).

At baseline, and every 6 weeks thereafter, self-reported depression, hopelessness, and suicide-related symptoms were assessed using the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) (13), Beck Hopelessness Scale (14), and Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire–Junior High School version (15), respectively. Anxiety symptoms and drug/alcohol use were assessed using the self-reported Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (16) and Drug Use Screening Inventory (17), respectively. Family conflict was assessed using the parent- and adolescent-reported Conflict Behavior Questionnaire (18).

Safety assessment

Safety assessments were completed during all pharmacotherapy visits and included a review of possible drug adverse effects, screening for symptoms of mania, and evaluation of suicidal thoughts and behavior as well as nonsuicidal self-injury (19).

After concerns about the safety of antidepressants were raised, safety assessments were increased to occur weekly, either in person or via telephone. Treatment-emergent adverse events were defined as new-onset or worsening of symptoms and were reviewed during weekly conference calls. Serious adverse events were those that resulted in significant disability, threat to life, or emergency care.

Outcomes

Response at 12 weeks was defined as a CGI improvement rating of ≤2 (much or very much improved) and a ≥50% decrease from baseline of the Children's Depression Rating Scale–Revised score. Remission was defined as at least 3 consecutive weeks without clinically significant depressive symptoms, corresponding to a score of 1 on the Adolescent Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation. Participants who responded by week 12 were assessed for relapse, indicating at least 2 consecutive weeks with probable or definite depressive disorder (score of 3 or 4 on the Adolescent Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation).

Data Analysis

The rates of and times to remission and relapse were compared across the initially assigned treatment groups using chi-square tests and Kaplan-Meier procedure, respectively. The baseline and week-12 demographic, clinical, and treatment characteristics of those individuals who attained remission and those who did not were compared using standard univariate statistics. The most parsimonious set of predictors of remission and time to remission was identified through backward stepwise logistic and Cox regressions. Because of similarities in the findings, only the results of the logistic regression are reported in the present study. With respect to the effect of open treatment on nonresponders, characteristics of individuals who received open treatment were coded for each 12-week interval, and the frequency of receipt of a given class of interventions was compared between the group of individuals who did remit and the group of those who did not remit using chi-square tests or Fisher's exact test. Data were analyzed using last observation carried forward. Analyses were repeated only for those participants who completed the assessments, and multiple imputation was performed with the missing at random assumption (20). The results from these analyses were very similar to the results from the last observation carried forward approach, and thus the last observation carried forward is reported. Analyses were conducted using SPSS 16.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago) and STATA 9.2 (StataCorp, LP, College Station, Tex.).

Results

Initial Treatment Assignment and Remission

The rate of and time to remission for individuals assigned to receive CBT plus medication were similar to the rate and time for those assigned to receive medication alone (rate of remission: N=61/166 [36.7%] versus N=69/168 [41.1%], χ2=0.66, df=1, p=0.42; time to remission: 12 weeks [interquartile range=9] versus 13 weeks [interquartile range=7]; hazard ratio=0.97, z=–0.16, p=0.87). Similar rate of and time to remission were also found between those individuals assigned to receive venlafaxine and those assigned to receive an SSRI (rate of remission: N=64/168 [38.1%] versus N=66/166 [39.8%], χ2=0.10, df=1, p=0.76; time to remission: 13 weeks [interquartile range=7] versus 13 weeks [interquartile range=8.5]; hazard ratio=1.06, z=0.31, p=0.76).

Initial Treatment Assignment and Relapse

Of 159 participants who responded at week 12 (3), six did not receive assessments beyond week 12 and could therefore not be assessed for relapse. Among the remaining 153 week-12 responders, the rate of and time to relapse for those assigned to receive CBT were similar to the rate and time for those assigned to receive medication alone (rate of relapse: N=20/86 [23.3%] versus N=10/67 [14.9%], χ2=1.66, df=1, p=0.20; time to relapse: 17 weeks [interquartile range=9] versus 14.5 weeks [interquartile range=7.5]; hazard ratio=1.64, z=1.28, p=0.20). The rate and time were also similar between those assigned to receive venlafaxine and those assigned to receive an SSRI (rate of relapse: N=16/77 [20.8%] versus N=14/76 [18.4%], χ2=0.05, df=1, p=0.82; time to relapse: 16.5 weeks [interquartile range=7.5] versus 18 weeks [interquartile range=8], hazard ratio=1.03, z=0.09, p=0.93).

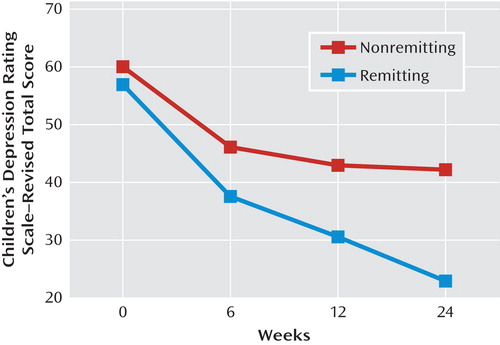

Clinical Predictors of Remission

The likelihood of remission was much higher and time to remission was faster among those individuals who showed clinical response by week 12 relative to those individuals who did not show response by week 12 (rate of remission: N=98/159 [61.6%] versus N=32/175 [18.3%], χ2=65.9, df=1, p<0.0001; time to remission: 12 weeks [interquartile range=7] versus 17.5 weeks [interquartile range=8], hazard ratio=4.43, z=7.27, p<0.001). In fact, the Children's Depression Rating Scale–Revised scores among individuals who did and did not remit began to diverge by week 6 (Figure 3). At 6 weeks, those participants who went on to remit showed a 47.5% (SD=29.6%) reduction in their scores on the scale from baseline, whereas those who did not remit showed a much lower rate of reduction in symptoms (27.5% [SD=30.4%]; t=–5.92, df=332, p<0.001).

aLog time: p<0.001; remission: p=0.07; remission-by-log time: p<0.001.

Among all participants, failure to achieve remission at 24 weeks was associated with high baseline and 12-week interviewer-rated and self-rated depression, hopelessness, anxiety, and family conflict. Additionally, at week 12, lower self-reported drug and alcohol use, suicidal ideation, interview-rated functioning and clinical severity, and diagnoses of anxiety and dysthymia all predicted a lack of remission (Table 1).

|

Backward stepwise logistic regression with the outcome of 24-week nonremission, including baseline predictors, identified higher baseline BDI scores as the single best predictor of failure to remit (odds ratio=1.03, 95% confidence interval [CI]=1.01–1.05, p=0.002). Similarly, the most parsimonious set of week-12 predictors of nonremission were Children's Depression Rating Scale–Revised scores (odds ratio=1.06, 95% CI=1.02–1.10, p=0.002), CGI severity ratings (odds ratio=1.48, 95% CI=1.01–2.17, p=0.04), dysthymia (odds ratio=2.70, 95% CI=1.00–7.30, p=0.05), and higher drug/alcohol use (odds ratio=2.07, 95% CI=1.22–3.52, p=0.007).

Predictors of Relapse Among Those Who Responded at Week 12

Of the 159 participants who responded by week 12, 30 (19.6%) relapsed by week 24. Predictors of relapse were similar to variables that predicted lack of eventual remission, which were baseline interview and self-reported depression, poorer functioning, and presence of dysthymia. Logistic regression selected self-reported depression as the single best predictor of relapse (odds ratio=1.06, 95% CI=1.01–1.10, p=0.003). Similar week-12 variables were associated with relapse, with the addition of a diagnosis of an anxiety disorder. Backward stepwise logistic regression identified week-12 interviewer-rated depression as the single best predictor of relapse (odds ratio=1.14, 95% CI=1.06–1.21, p<0.001).

Additional Treatment Strategies and Remission Among Nonresponders

Among nonresponders, those whose treatment was augmented with a mood stabilizer (atypical antipsychotic [N=6], lithium [N=2], divalproex [N=1], topiramate [N=1]) during the first 12 weeks of treatment were more likely to remit relative to nonresponders whose treatment was not augmented with a mood stabilizer (N=5/10 [50%] versus N=27/153 [17%]; Fisher's exact test: p=0.03) but not if the augmentation took place during the second 12 weeks (N=5/14 [35.7%] versus N=25/116 [21.6%], p=0.31). While not statistically significant, those who were switched from their randomly assigned SSRI to venlafaxine (i.e., venlafaxine was the third antidepressant trial) were more likely to remit relative to the remainder of the group (odds ratio=1.53, 95% CI=0.40–5.81), whereas those who were switched from venlafaxine to an SSRI were less likely to respond to treatment relative to the remainder of nonresponders in the venlafaxine group (odds ratio=0.22, 95% CI=0.03–1.84). The test of the homogeneity of the odds ratios favored switching from an SSRI to venlafaxine, although it escaped statistical significance (Breslow-Day test: χ2=2.57, df=1, p=0.11). Among nonresponders, participants who received an antidepressant that was neither an SSRI nor a serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, either as a switch medication or as an augmentation agent in the second 12 weeks, showed a nearly significant difference toward lower rates of remission relative to the remaining nonresponders (N=0/11 [0.0%] versus N=30/119 [25.2%]; Fisher's exact test: p=0.07).

Among nonresponders who had not initially been assigned to receive CBT, the receipt of additional psychotherapy during the first 12 weeks was associated with a higher rate of remission (N=11/29 [37.9%] versus N=11/71 [15.5%], χ2=6.04, df=1, p=0.01). However, this association with remission was not found when the receipt of additional psychotherapy occurred during the second 12 weeks (N=15/52 [28.8%] versus N=7/31 [22.6%], χ2=0.39, df=1, p=0.53).

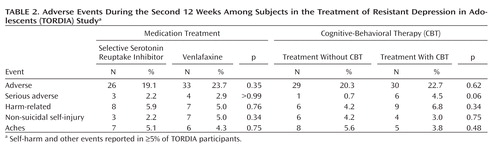

Safety Findings

Table 2 reports the side effects and adverse events that occurred in more than 5% of the sample. These results must be interpreted cautiously because only one-third of individuals in the sample were in their initially assigned treatment group by the end of the study. There were no statistically significant treatment differences, although there was a nearly significant difference toward a higher rate of serious adverse events in the CBT assigned groups.

|

Discussion

In a sample of chronically depressed adolescents who had already failed to respond to an adequate trial of SSRI treatment, nearly 40% achieved remission after 6 months of randomly assigned treatment in the TORDIA study. Initial treatment assignment did not affect the rates of remission, but greater clinical severity of depression predicted both failure to remit and, among responders, greater likelihood of relapse. By week 6, the rate of decrease of depressive symptoms among those who remitted had already begun to diverge from the rate among those who did not remit.

The rate of remission in the TORDIA study at 24 weeks was lower than the reported rate of 60% in the Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS), despite similar lengths of treatment (21). Treatment-resistant depressed samples show lower rates of remission with each subsequent treatment step (22). The TORDIA study sample had greater chronicity and higher levels of suicidal ideation than the TADS sample, both of which have been shown to predict a less robust treatment response (23, 24).

Our findings point to the importance of the early trajectory of treatment response in determining remission after 6 months. Initial response at 12 weeks predicted a greater than threefold increased likelihood of remission. Moreover, the clinical course of those who eventually remitted already began to diverge by 6 weeks of treatment, with individuals who remitted showing a rate of decline in symptoms that was nearly twice the rate found among those who did not remit after 6 months, which is consistent with a previous report (25).

In addition, among nonresponders, augmentation with either a mood stabilizer or psychotherapy offered during the first 12 weeks of treatment resulted in eventual remission. These augmentation findings parallel those in controlled trials of adolescents and adults (22, 26–28). The same interventions offered during the second 12 weeks of treatment did not affect the remission rates among nonresponders.

We found no enduring effects of initial treatment assignment to CBT with respect to remission, protection from relapse, and protection from adverse events. Other studies have also shown that the effects of various initial treatments converge over time (21, 29, 30), and while one study found protective effects of CBT against adverse events, another did not (31, 32). A greater number of sessions of CBT might be required to prevent relapse (27, 33). The open treatment provided in the TORDIA study, such as offering CBT to nonresponders who initially did not receive it, also contributed to the convergence of outcomes among the different treatment arms.

Counter to hypotheses and some reports on depressed adults, we did not find that treatment with venlafaxine was superior to treatment with SSRIs in achieving remission, although the TORDIA study was not powered to detect risk differences of 5%–10% (34, 35). We did find a nearly significant difference for a switch from an SSRI to venlafaxine in a third treatment step, which showed a relatively better remission rate than vice versa.

In addition to clinical severity, we also identified other clinical variables that predicted a failure to remit, namely family conflict, drug and alcohol use, and anxiety disorder, consistent with our initial predictors of response and other studies (4, 24, 30, 36, 37). These clinical variables, assessed after acute treatment, frame treatment strategies that could substantially increase the rate of remission.

There are several limitations to be considered when evaluating the results of this study. Many participants were in open treatment by week 24, making it difficult to evaluate the relationship between initial treatment assignment and outcome, especially because open treatment was not assigned randomly and there were small numbers of each type of open treatment. In addition, there was no placebo-comparison group, making it impossible to compare the outcomes obtained with study interventions with the natural history of the disorder. While up to 80% of depressed youth eventually remit, the expected rate is lower among those with more chronic depression (38). Finally, approximately 20% of participants did not complete the week-24 assessment or had unknown medication status, and these individuals had a lower rate of initial response and most likely would have been less likely to remit as well had they been retained.

These findings suggest that current clinical guidelines, which recommend pursuing a given treatment strategy for at least 8–12 weeks, may need to be revisited. Instead, our data support more vigorous intervention earlier in the course of treatment for nonresponding patients. Clinicians may consider incorporating potentially promising strategies such as augmentation of antidepressants with psychotherapy or mood stabilizers, recognizing that clinical trials have only been conducted among adults for these treatments. In addition, when indicated, broadening treatment targets to include comorbid anxiety, alcohol and substance use, and family conflict may be important in achieving remission and preventing relapse. Further research is recommended to identify both promising intervention strategies and the optimal time for their implementation when a depressed adolescent is not responding to current treatment.

1 : Clinical response and risk for reported suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in pediatric antidepressant treatment: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAMA 2007; 297:1683–1696 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2 : Effects of psychotherapy for depression in children and adolescents: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull 2006; 132:132–149 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3 : Switching to another SSRI or to venlafaxine with or without cognitive behavioral therapy for adolescents with SSRI-resistant depression: the TORDIA randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2008; 299:901–913 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4 : Treatment of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor-resistant depression in adolescents: predictors and moderators of treatment response. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2009; 48:330–339 Medline, Google Scholar

5 : Predictors of spontaneous and systematically assessed suicidal adverse events in the Treatment of SSRI-Resistant Depression in Adolescents (TORDIA) study. Am J Psychiatry 2009; 166:418–426 Link, Google Scholar

6 American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed (DSM–IV). Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Publishing, 1994 Google Scholar

7 : Effective components of TORDIA cognitive behavioral therapy or adolescent depression. J Consult Clin Psychol 2009; 77:1033–1041 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8 : Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children–Present and Lifetime version (K–SADS–PL): initial reliability and validity data. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997; 36:980–988 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9 : Children's Depression Rating Scale–Revised (CDRS–R). Los Angeles, Western Psychological Services, 1996 Google Scholar

10 : ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology, 2nd ed. Rockville, Md, National Institute of Health, 1976, pp 76–338 Google Scholar

11 : A Children's Global Assessment Scale (CGAS). Arch Gen Psychiatry 1983; 40:1228–1231 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12 : The Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation: a comprehensive method for assessing outcome in prospective longitudinal studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1987; 44:540–548 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13 : Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: twenty-five years of evaluation. Clin Psychol Rev 1988; 8:77–100 Crossref, Google Scholar

14 : The measurement of pessimism: the Hopelessness Scale. J Consult Clin Psychol 1974; 42:861–865 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15 : Assessment of suicidal ideation in inner-city children and young adolescents: reliability and validity of the Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire–JR. School Psychol Rev 1999; 28:17–30 Google Scholar

16 : Psychometric properties of the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED): a replication study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1999; 38:1230–1236 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17 : Norms and sensitivity of the adolescent version of the Drug Use Screening Inventory. Addict Behav 1995; 20:149–157 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18 : Negotiating Parent-Adolescent Conflict: A Behavioral Family Systems Approach. New York, Guilford Press, 1989 Google Scholar

19 : Measuring mood and complex behavior in natural environments: use of ecological momentary assessment in pediatric affective disorders. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2003; 13:253–266 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20 : Statistical Analysis With Missing Data, 2nd ed. New York, John Wiley and Sons, 2002 Crossref, Google Scholar

21 : Remission and recovery in the Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS): acute and long-term outcomes. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2009; 48:186–195 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22 : Acute and longer-term outcomes in depressed outpatients requiring one or several treatment steps: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163:1905–1917 Link, Google Scholar

23 : Treatment of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor-resistant depression in adolescents: predictors and moderators of treatment response. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2009; 48:330–339 Medline, Google Scholar

24 : Predictors and moderators of acute outcome in the Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2006; 45:1427–1439 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25 : Early prediction of acute antidepressant treatment response and remission in pediatric major depressive disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2009; 48:71–78 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26 : Augmentation strategies to increase antidepressant efficacy. J Clin Psychiatry 2007; 68(suppl 10):18–22 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27 : Cognitive-behavioral therapy to prevent relapse in pediatric responders to pharmacotherapy for major depressive disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2008; 47:1395–1404 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28 : Atypical antipsychotic augmentation in major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of placebo-controlled randomized trials. Am J Psychiatry 2009; 166:980–991 Link, Google Scholar

29 : Controlled trial of a brief cognitive-behavioral intervention in adolescent patients with depressive disorders. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1996; 37:737–746 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30 : Clinical outcome after short-term psychotherapy for adolescents with major depressive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000; 57:29–36 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31 : Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS): safety results. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2006; 45:1440–1455 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32 : Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and routine specialist care with and without cognitive behaviour therapy in adolescents with major depression: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2007; 335:142 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33 : Pilot study of continuation cognitive-behavioral therapy for major depression in adolescent psychiatric patients. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1996; 35:1156–1161 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34 : The effect of venlafaxine compared with other antidepressants and placebo in the treatment of major depression: a meta-analysis. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2009; 259:172–185 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35 : Are SNRIs more effective than SSRIs?: a review of the current state of the controversy. Psychopharmacol Bull 2008; 41:58–85 Medline, Google Scholar

36 : Concurrent anxiety and substance use disorders among outpatients with major depression: clinical features and effect on treatment outcome. Drug Alcohol Depend 2009; 99:248–260 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37 : Substance use and the treatment of resistant depression in adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry (Epub ahead of print, Oct 23, 2009) Crossref, Google Scholar

38 : Course and outcome of child and adolescent major depressive disorder. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am 2002; 11:619–637 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar