Atypical Antipsychotic Augmentation in Major Depressive Disorder: A Meta-Analysis of Placebo-Controlled Randomized Trials

Abstract

Objective: The authors sought to determine by meta-analysis the efficacy and tolerability of adjunctive atypical antipsychotic agents in major depressive disorder. Method: Searches were conducted of MEDLINE/PubMed (1966 to January 2009), the Cochrane database, abstracts of major psychiatric meetings since 2000, and online trial registries. Manufacturers of atypical antipsychotic agents without online registries were contacted. Trials selected were acute-phase, parallel-group, double-blind controlled trials with random assignment to adjunctive atypical antipsychotic or placebo. Patients had nonpsychotic unipolar major depressive disorder that was resistant to prior antidepressant treatment. Response, remission, and discontinuation rates were either reported or obtained. Data were extracted by one author and checked by the second. Data included study design, number of patients, patient characteristics, methods of establishing treatment resistance, drug doses, duration of the adjunctive trial, depression scale used, response and remission rates, and discontinuation rates for any reason or for adverse events. Results: Sixteen trials with 3,480 patients were pooled using a fixed-effects meta-analysis. Adjunctive atypical antipsychotics were significantly more effective than placebo (response: odds ratio=1.69, 95% CI=1.46–1.95, z=7.00, N=16, p<0.00001; remission: odds ratio=2.00, 95% CI=1.69–2.37, z=8.03, N=16, p<0.00001). Mean odds ratios did not differ among the atypical agents and were not affected by trial duration or method of establishing treatment resistance. Discontinuation rates for adverse events were higher for atypical agents than for placebo (odds ratio=3.91, 95% CI=2.68–5.72, z=7.05, N=15, p<0.00001). Conclusions: Atypical antipsychotics are effective augmentation agents in major depressive disorder but are associated with an increased risk of discontinuation due to adverse events.

Depression is among the most common medical disorders. In the United States approximately 1 in 6 individuals will suffer from major depressive disorder during their lifetime (1) . Even though numerous treatments are available, only about one-third of patients receiving initial antidepressant treatment achieve remission (2) . As a consequence, several treatment strategies have evolved for difficult-to-treat depression. One approach has been to augment antidepressants with an agent not approved for use as monotherapy in major depressive disorder.

Augmentation strategies have a long history. Use of stimulants and T 3 to augment tricyclic antidepressants was described four decades ago (3) . Subsequently, use of several other agents for augmentation was described, but the evidence base comprised a limited number of controlled trials with small samples. Until recently lithium augmentation was the best studied augmentation strategy. Ten placebo-controlled trials were performed, but nine of them included no more than 35 patients (4) . In 10 controlled lithium studies, the total number of patients was only 269 (4) , and in the majority of these studies lithium was used to augment tricyclic antidepressants, which are not currently in widespread use.

The use of antipsychotic agents in depression has a long history (5) , but recognition of the extrapyramidal side effects and the risk of tardive dyskinesia discouraged the use of the conventional antipsychotics. However, the advent of a newer generation of antipsychotic agents, which for the most part appeared to differ from conventional agents in their side effect and neuropharmacologic profile, rekindled interest in the use of this class of drugs in mood and anxiety disorders, including as adjunctive therapy. The first report of the use of an atypical antipsychotic for augmentation in major depressive disorder appeared in 1999. Ostroff and Nelson (6) described eight patients whose depression had failed to respond to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). Rapid effects were noted when low doses of risperidone were added. This observation was soon followed by the first placebo-controlled study. Shelton et al. (7) noted that the combination of olanzapine and fluoxetine was more effective than either drug alone in a sample of 30 patients with fluoxetine-resistant major depression. Since those initial reports, the number and size of studies of augmentation with atypical antipsychotics has grown rapidly, and in 2008 aripiprazole became the first atypical agent and the first pharmacologic treatment of any type to be approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use as an augmentation agent in major depressive disorder.

With the growth of the adjunctive use of atypical antipsychotics, interest in their efficacy and tolerability has increased. In 2007 Papakostas et al. (8) conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of 10 placebo-controlled augmentation trials of atypical antipsychotics for major depressive disorder (N=1,500). The meta-analysis confirmed the efficacy of this strategy. Since that meta-analysis was published, however, six new trials with 2,007 subjects have been published or presented at major scientific meetings; these include three large trials of aripiprazole (9 – 11) , as well as two large trials of extended-release quetiapine (12 , 13) , that increase the number of subjects treated with quetiapine from 109 to 1,028. Because the growth of evidence for the use of atypicals has been so rapid, an updated review and meta-analysis of the efficacy and tolerability of these agents is in order.

Given differences in the neuropharmacology of atypical antipsychotics (14 – 16) , it is not clear that these agents would have similar efficacy in depression or that they would be effective in the same patients. Moreover, the dosages used in the adjunctive treatment of depression are often lower than those used in the treatment of psychotic disorders, and the prominent pharmacologic effects may differ between these dosage levels. All of the atypical antipsychotics display 5-HT 2 receptor antagonism, although their relative potency varies. Aripiprazole and ziprasidone also display 5-HT 1A partial agonism (15) . All of the atypical agents possess dopamine D 2 receptor affinity; aripiprazole acts as a partial agonist at this receptor (17) , and the others have antagonist properties. The metabolite of quetiapine, N -desalkylquetiapine, has recently been shown to have moderate affinity for the norepinephrine reuptake transporter (18) , but it is not clear that the metabolite achieves appreciable plasma concentrations in human subjects. Ziprasidone is associated with notable potency at the transporters for dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin (19) . The olanzapine-fluoxetine combination is reported to produce a greater increase in extracellular levels of dopamine and norepinephrine in rat prefrontal cortex than either agent alone or other combinations of antipsychotics and SSRIs (20) . Each of these effects might contribute to clinical efficacy in depression. Alternatively, these effects as well as varying levels of a 1 adrenergic, antihistaminic, and antimuscarinic activity of these agents may produce differences in side effects.

In our meta-analysis, we hypothesized that adjunctive treatment with atypical antipsychotics would result in higher rates of response and remission than placebo but that this effect would be offset to some extent by an increase in discontinuation due to adverse events. We further hypothesized that sensitivity analyses would reveal that adjunctive trials of longer duration would be associated with larger drug-placebo differences and that studies using a prospective trial to confirm treatment resistance would have lower response rates but greater drug-placebo differences.

Method

We searched MEDLINE/PubMed (1966 to January 2009) for randomized placebo-controlled trials of atypical antipsychotic agents approved by the FDA for any indication. Search terms were “major depression” and “aripiprazole or olanzapine or paliperidone or quetiapine or risperidone or ziprasidone.” The Cochrane Clinical Trials register was searched using identical terms. Poster presentations at major psychiatric meetings since 2000 were searched, and the manufacturers of atypical antipsychotic medications were asked for all published and unpublished reports of adjunctive trials in nonpsychotic major depressive disorder. Reports from different sources were then compared to identify nonduplicative trials.

Trial Selection

Trials were included if they were acute-phase, parallel-group, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials with random assignment to adjunctive treatment with an atypical antipsychotic or placebo. Patients had to have nonpsychotic major depressive disorder that was considered treatment resistant either by history or determined by a prospective trial. Response, remission, and discontinuation rates either were reported in published articles or poster presentations or were obtained from the sponsor or investigator.

Data Extraction

Data were extracted by one of the authors and checked for accuracy by the other. Data extracted included study design, number of patients, patient characteristics, methods used to establish treatment resistance, drug dosages, duration of the prospective adjunctive trial, response and remission rates, and rates of discontinuation for any reason and for adverse events. Response was defined as an improvement of ≥50% from baseline to endpoint on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (21) or the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (22) in the intent-to-treat sample using the last-observation-carried-forward method. Remission was defined according to each individual trial in the intent-to-treat/last-observation-carried-forward sample.

Statistical Analysis

Across studies, the numbers of patients who responded, remitted, and dropped out and the number randomly assigned to each treatment group were statistically combined, using a fixed-effects meta-analytic model. Effects were expressed as odds ratios with their 95% confidence intervals (CIs), test of significance (Wald’s z), number (N) of contrasts, and p values. Effects were calculated for each drug-placebo contrast, for each group of trials using the same drug, and as meta-analytic summaries for all drugs combined. A funnel plot in which the standard error of the log odds ratio against the log of the odds ratio was used to evaluate potential publication or retrieval bias.

Chi-square tests and the I 2 statistic derived from the chi-square values were used to test for heterogeneity among the studies. I 2 approximates the proportion of total variation in the effect size estimates that is due to heterogeneity rather than sampling error (23) . An alpha error <0.20 and an I 2 of at least 50% were taken as indicators of heterogeneity. In the Results section, the chi-square test and I 2 statistics for heterogeneity follow the 95% CI, z score, N, and p value for the odds ratio unless these values are provided in a figure.

In sensitivity analyses, we compared subgroups on potential differences between the different agents, duration of the adjunctive trial, and definition of treatment resistance (historical or prospective). Differences between two or more subgroups were investigated by subtracting the sum of the heterogeneity chi-square statistics of the subgroups from the overall chi-square statistic and comparing the result with a chi-square distribution with the value for degrees of freedom 1 less than the number of subgroups (24) . Review Manager, version 4.2 (Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, England), was used for statistical calculations.

Results

Figure 1 illustrates the search flow. The MEDLINE and Cochrane searches each found 10 nonduplicative reports of 11 randomized, double-blind controlled trials of acute-phase treatment with atypical antipsychotic augmentation in patients with nonpsychotic major depressive disorder patients who had not responded to prior antidepressant treatment (either by history or in a prospective trial). The search of meeting abstracts and information provided by the manufacturers of atypical antipsychotics provided another five unpublished reports that were presented as posters. We excluded five trials of patients with psychotic depression, one relapse prevention trial, one secondary analysis, three open-label trials, two acceleration trials, and four other studies that did not investigate efficacy (focusing instead, for example, on effects on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis).

The 15 reports of 16 trials included five trials with olanzapine (7 , 25 – 27) , three with risperidone (28 – 30) , five with quetiapine (12 , 13 , 31 – 33) , and three with aripiprazole (9 – 11) . No acute-phase, double-blind trials of adjunctive ziprasidone or paliperidone in major depressive disorder were found. The 16 trials included a total of 3,480 patients, of whom 2,014 were randomly assigned to adjunctive treatment with an atypical antipsychotic and 1,466 to placebo. Other descriptive features of the trials are listed in Table 1 . In one report for olanzapine (27) , discontinuation rates were presented as combined data from two individual trials, so the two trials were presented as a single trial in the meta-analysis of discontinuation rates.

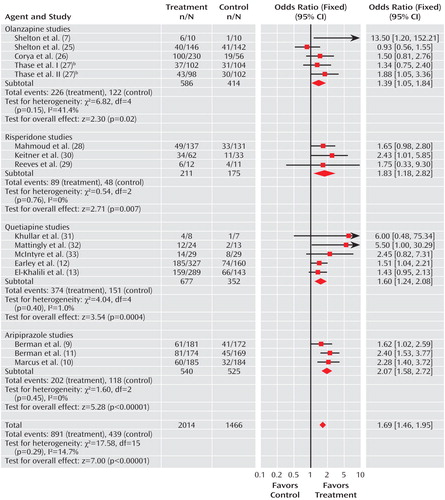

Response and Remission

The meta-analyses for response and remission are summarized in Figures 2 and 3 . The odds ratio for response with drug versus placebo was 1.69 (95% CI=1.46–1.95, z=7.00, N=16, p<0.00001). The risk difference by meta-analysis was 0.12 (95% CI=0.08–0.15, z=7.14, N=16, p<0.00001). The risk difference translates into a number needed to treat of nine. The test for heterogeneity indicated a lack of heterogeneity (χ 2 =17.58, df=15, p=0.29, I 2 =14.7%). The overall pooled response rate for treatment with an atypical agent was 44.2%, compared with 29.9% for placebo.

a Odds ratios for response on drug and placebo are grouped by atypical agent.

b This report included two separate trials of identical design.

a Odds ratios for remission on drug and placebo are grouped by atypical agent.

b This report included two separate trials of identical design.

Odds ratios for the trials grouped by atypical agent varied from 1.39 (95% CI=1.05–1.84) to 2.07 (95% CI=1.58–2.72), with considerable overlap among the confidence intervals. Testing the difference between the atypical subgroups indicated no significant differences (χ 2 =4.58, df=3, p=0.21).

The odds ratio for remission was 2.00 (95% CI=1.69–2.37, z=8.03, N=16, p<0.00001). The risk difference for remission was 0.12 (95% CI=0.09–0.15), indicating a number needed to treat of nine. The test for heterogeneity was not significant (χ 2 =8.16, df=15, p=0.92, I 2 =0%). The pooled remission rates were 30.7% for atypical antipsychotics, compared with 17.2% for placebo.

The odds ratios for remission varied from 1.83 to 2.63 among the drug subgroups, with overlapping confidence intervals. Testing the difference between the atypical subgroups indicated no significant differences (χ 2 =1.50, df=3, p=0.68).

Discontinuation Rates

The odds ratio comparing drug and placebo groups for rates of discontinuation for any reason was 1.30 (95% CI=1.09–1.57, z=2.85, p=0.004) ( Figure 4 ). The test for heterogeneity was not significant (χ 2 =13.04, df=14, p=0.52, I 2 =0%). The odds ratios for rates of discontinuation for any reason did not differ significantly among the drug subgroups (χ 2 =1.60, df=3, p=0.66). The pooled actual rates of discontinuation for any reason were 19.6% in the atypical treatment group and 15.5% in the placebo group.

a Odds ratios for rates of discontinuation for any reason on drug and placebo are grouped by atypical agent.

The odds ratio for the rate of discontinuation for adverse events with drug and placebo was 3.91 (95% CI=2.68–5.72, z=7.05, N=15, p<0.00001) ( Figure 5 ). The test for heterogeneity was not significant (χ 2 =8.73, df=10, p=0.56, I 2 =0%). The risk difference was 0.06 (95% CI=0.05–0.08), resulting in a number needed to harm of 17. The pooled adverse event discontinuation rates were 9.1% in the atypical antipsychotic group and 2.3% in the placebo group. The odds ratios for the subgroups varied from 2.68 to 5.52. Testing the difference between the atypical subgroups indicated no significant differences (χ 2 =0.66, df=3, p=0.88).

a Odds ratios for discontinuation rates due to adverse events on drug and placebo are grouped by atypical agent.

Trial duration varied from 4 to 12 weeks. Duration of the trial did not significantly affect the odds ratio for response to drug and placebo ( Figure 6 ). The odds ratios for trials of 4, 6, 8, and 12 weeks were 2.43 (95% CI=1.01–5.85), 1.83 (95% CI=1.50–2.25), 1.50 (95% CI=1.19–1.89), and 1.50 (0.81–2.76), respectively, and did not differ significantly (χ 2 =2.63, df=3, p=0.45). This analysis, however, was limited because only one trial had a duration of 4 weeks and only one of 12 weeks.

a This report included two separate trials of identical design.

We also examined whether the odds ratios for response differed in trials using history of drug failure rather than a prospective trial to establish treatment resistance ( Figure 7 ). Ten of the trials required that patients have failed to respond in one prospective trial, and six required that patients have a history of nonresponse or failed to respond in the current trial. The odds ratio of the 10 trials requiring a failed prospective trial was 1.73 (95% CI=1.45–2.06), which did not differ from the trials using only historical data, in which the odds ratio was 1.61 (95% CI=1.24–2.08). The magnitude of the drug-placebo difference, estimated by the risk difference from the meta-analysis, was identical using the two methods, at 0.12. However, the pooled response rates in trials requiring a failed prospective trial (38.6% [511/1,325] and 25.8% [284/1,103] for drug and placebo, respectively) were considerably lower than response rates in trials using historical data (55.2% [380/689] and 42.7% [155/363], respectively), suggesting that patients who did not respond in prospective treatment were more treatment resistant. All but two of the trials continued with the original antidepressant during the adjunctive trials. Two of the olanzapine trials switched to olanzapine plus fluoxetine after using a different antidepressant during the prospective trial. When these two trials were excluded from the analysis, the odds ratio for trials requiring nonresponse in a prospective trial was slightly higher at 1.93 (95% CI=1.58–2.36) but still not significantly different from that in the trials requiring historical nonresponse.

a This report included two separate trials of identical design.

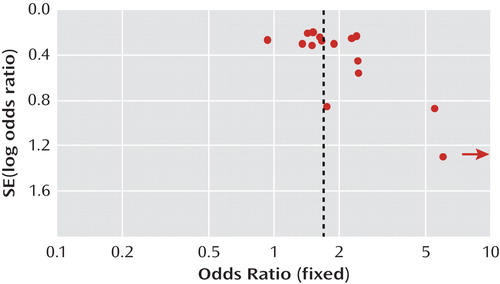

A funnel plot of the odds ratios for response plotted against standard error (log odds ratio) was asymmetric, with three of four small studies (N<25 per arm) showing high odds ratios ( Figure 8 ). When these four trials were excluded, however, the odds ratio for response was relatively unaffected (1.64 [95% CI=1.42–191] compared with 1.69 [95% CI=1.46–196]).

Discussion

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, 15 reports of 16 adjunctive trials were pooled. Augmentation with atypical antipsychotic agents was significantly more effective than placebo for response and remission. The odds ratio for remission was 2.00, with a number needed to treat of nine. No significant differences in efficacy were noted among the different atypical agents (olanzapine, risperidone, quetiapine, and aripiprazole). The relative efficacy of the atypical agents compared with placebo in augmentation did not appear to be influenced by the duration of the adjunctive trial or by whether treatment resistance was determined using a prospective trial or historical nonresponse.

At present, this body of evidence is considerably larger than that for any other augmentation strategy in the treatment of major depressive disorder. For example, the 10 controlled trials of lithium cited earlier (4) included only 269 patients, whereas these 16 trials of atypical antipsychotics included 3,480 patients. In addition, the early trials of lithium and T 3 augmentation often required minimal evidence of treatment resistance, for example, 4 weeks of failure to respond to the initial antidepressant. The only placebo-controlled lithium augmentation trial to retrospectively and prospectively establish treatment resistance (34) failed to find lithium effective. All of the trials of atypicals required evidence of treatment resistance, and for several of the trials, patients had failed to respond to more than one antidepressant.

Although the funnel plot of the odds ratios was asymmetric for the smaller studies and thus suggestive of publication or retrieval bias, exclusion of the smaller studies from the meta-analysis had essentially no effect on the odds ratio. After a thorough literature search as well as contact with the manufacturers of all the atypical agents approved for use in the United States, we are reasonably confident that we have included all of the larger studies that have been completed. An asymmetric funnel plot is only suggestive of bias. It might be argued that smaller studies with a limited number of sites and careful patient selection may produce more valid results.

We used a fixed-effects model for the meta-analysis because the patient samples were reasonably homogeneous, the study designs were similar, and all studies used either the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale or the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale to rate response. Tests for heterogeneity were not statistically significant. Had we employed a random-effects model, the results for response (odds ratio=1.69, 95% CI=1.43–2.00, z=6.21, p<0.00001) and remission (odds ratio=1.99, 95 CI=1.68–2.36, z=7.95, p<0.00001) would have been nearly identical to those obtained using a fixed-effects model.

While the efficacy of the atypical agents for adjunctive therapy in major depressive disorder appears fairly well established, there are other considerations. The rate of discontinuation due to adverse events was significantly higher for the atypical group (9.1%) than the placebo group (2.3%). The risk difference by meta-analysis was 0.06, with a number needed to harm of 17. While the discontinuation rates did not differ significantly among the agents, rates of specific side effects may be quite different. In addition, during continuing treatment there may be other secondary effects that in the aggregate affect tolerability and patient acceptance. The atypical agents also are associated with a variety of relatively serious adverse effects, such as metabolic syndrome, extrapyramidal symptoms, and rare but serious symptoms such as tardive dyskinesia and neuroleptic malignant syndrome. As a consequence the risk-benefit ratio appears to be different from that of several alternative treatments for major depressive disorder. Because of these risks, the Texas Algorithm Group (M.H. Trivedi et al., unpublished 2007 data) placed the atypical antipsychotics below some other augmentation agents (e.g., lithium and thyroid) even though the efficacy data are stronger for the atypicals. Finally, little is known about efficacy and safety of the atypicals during continuation and maintenance treatment in major depression.

There are limitations to this analysis. There may be other studies with different results that were not published or presented and thus were not included in our analysis. Definitions of treatment resistance are still evolving, and there is no standard for studies such as these. Yet the methods used to define treatment resistance in these trials of augmentation with atypical agents were more rigorous than those of previous augmentation trials. While the total number of patients included in these trials (N=3,480) is fairly large, the number of trials on which this trial-level data analysis is based is limited. This limitation is even more important when comparing subgroups. While risperidone was studied in three trials, the samples of two of the trials, 23 and 95, were relatively small, and the total number studied was 386. The other three agents were studied in at least 1,000 patients. While adjunctive olanzapine appears to be effective, the trials all examined adjunctive treatment with fluoxetine. The efficacy of olanzapine combined with other antidepressants has not been well studied.

In addition to factors limiting this analysis, there are several limitations to the existing clinical literature regarding the use of atypicals in depression. For each of these agents, limited data are available for establishing an effective dosage range during adjunctive treatment of depression. Even if efficacy in groups of patients is similar among these agents, it is not clear that patients of the same profile are responding. This would seem unlikely given the differences in neuropharmacology among these agents. Individual patients may respond better to one agent than to another; yet methods to tailor treatment to the patient have not been established. Given the cost and safety issues for the atypical agents, it will be important to compare their efficacy and safety with those of other, less expensive augmentation and combination strategies in depression. Finally, all of the trials we reviewed were of short duration. Long-term efficacy and safety data are sorely needed. In addition, even if continuing adjunctive treatment is shown to reduce relapse rates, because of the increased side effect burden and cost of continuing two agents, there will be additional questions. For example, if a patient remits with adjunctive treatment, can the initial antidepressant be discontinued? If so, when and in which patients? Alternatively, can individuals be identified who will remain in remission if the atypical agent is withdrawn? These questions deserve study.

1. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Koretz D, Merikangas KR, Rush AJ, Walters EE, Wang PS: The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey replication (NCS-R). JAMA 2003; 289:3095–3105Google Scholar

2. Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, Nierenberg AA, Stewart JW, Warden D, Niederehe G, Thase ME, Lavori PW, Lebowitz BD, McGrath PJ, Rosenbaum JF, Sackeim HA, Kupfer DJ, Luther J, Fava M: Acute and longer-term outcomes in depressed outpatients requiring one or several treatment steps: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163:1905–1917Google Scholar

3. Nelson JC: Augmentation strategies for treatment of unipolar major depression, in Mood Disorders: Systematic Medication Management, vol 25, Modern Problems of Pharmacopsychiatry. Edited by Rush AJ. Basel, Karger, 1997, pp 34–55Google Scholar

4. Crossley NA, Bauer M: Acceleration and augmentation of antidepressants with lithium for depressive disorders: two meta-analyses of randomized, placebo-controlled trials. J Clin Psychiatry 2007; 68:935–940Google Scholar

5. Nelson JC: The use of antipsychotic drugs in the treatment of depression, in Treating Resistant Depression. Edited by Zohar J, Belmaker RH. New York, PMA Publishing, 1987, pp 131–146Google Scholar

6. Ostroff RB, Nelson JC: Risperidone augmentation of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in major depression. J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 60:256–259Google Scholar

7. Shelton RC, Tollefson GD, Tohen M, Stahl S, Gannon KS, Jacobs TG, Buras WR, Bymaster FP, Zhang W, Spencer KA, Feldman PD, Meltzer HY: A novel augmentation strategy for treating resistant major depression. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:131–134Google Scholar

8. Papakostas GI, Shelton RC, Smith J, Fava M: Augmentation of antidepressants with atypical antipsychotic medications for treatment-resistant major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry 2007; 68:826–831Google Scholar

9. Berman RM, Marcus RN, Swanink R, McQuade RD, Carson WH, Corey-Lisle PK, Khan A: The efficacy and safety of aripiprazole as adjunctive therapy in major depressive disorder: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry 2007; 68:843–853Google Scholar

10. Marcus R, McQuade R, Carson W, Hennicken D, Fava M, Simon J, Trivedi M, Thase M, Berman R: The efficacy and safety of aripiprazole as adjunctive therapy in major depressive disorder: a second multicenter, randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2008; 28:156–165Google Scholar

11. Berman RB, Fava M, Thase ME, Trivedi MH, Swanink R, McQuade RD, Carson WH, Adson D, Taylor L, Hazel J, Marcus RN: The third consecutive, positive, double-blind, placebo controlled trial of aripiprazole augmentation in the treatment of major depression, in American College of Neuropsychopharmacology 2008 Annual Meeting Abstracts (Scottsdale, Ariz, Dec 7–11, 2008). Nashville, Tenn, ACNP, 2008Google Scholar

12. Earley W, McIntyre A, Bauer M, Pretorius HW, Shelton R, Lindgren P, Brecher M: Efficacy and tolerability of extended release quetiapine fumarate (quetiapine extended release) as add-on to antidepressants in patients with major depressive disorder (MDD): results from a double-blind, randomized, phase III study, in American College of Neuropsychopharmacology 2007 Annual Meeting Abstracts (Boca Raton, Fla, Dec 9–13, 2007). Nashville, TN, ACNP, 2007Google Scholar

13. El-Khalili N, Joyce M, Atkinson S, Buynak R, Datto C, Lindgren P, Eriksson H, Brecher M: Adjunctive extended-release quetiapine fumarate (quetiapine-extended release) in patients with major depressive disorder and inadequate antidepressant response, in American Psychiatric Association 2008 Annual Meeting: New Research Abstracts (Washington, DC, May 3–8, 2008). Washington, DC, APA, 2008Google Scholar

14. Reynolds GP: Receptor mechanisms in the treatment of schizophrenia. J Psychopharmacology 2004; 18:340–345Google Scholar

15. Stahl SM, Shayegan DK: The psychopharmacology of ziprasidone: receptor-binding properties and real-world psychiatric practice. J Clin Psychiatry 2003; 64(suppl 19):6–12Google Scholar

16. Farah A: Atypicality of atypical antipsychotics. Prim Care Companion. J Clin Psychiatry 2005; 7:268–274Google Scholar

17. Tadori Y, Forbes RA, McQuade RD, Kikuchi T: Characterization of aripiprazole partial agonist activity at human dopamine D(3) receptors. Eur J Pharmacol 2008; 597:27–33Google Scholar

18. Jensen NH, Rodriguiz RM, Caron MG, Wetsel WC, Rothman RB, Roth BL: N-desalkylquetiapine, a potent norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor and partial 5-HT 1A agonist, as a putative mediator of quetiapine’s antidepressant activity. Neuropsychopharmacology 2008; 33:2303–2312 Google Scholar

19. Tatsumi M, Jansen K, Blakely RD, Richelson E: Pharmacologic profile of neuroleptics at human monoamine transporters. Eur J Pharmacol 1999; 368:277–283Google Scholar

20. Zhang W, Perry KW, Wong DT, Potts BD, Bao J, Tollefson GD, Bymaster FP: Synergistic effects of olanzapine and other antipsychotic agents in combination with fluoxetine on norepinephrine and dopamine release in rat prefrontal cortex. Neuropsychopharmacology 2000; 23:250–262Google Scholar

21. Hamilton M: A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1960; 23:56–61Google Scholar

22. Montgomery SA, Åsberg M: A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry 1979; 134:382–389Google Scholar

23. Higgins JP, Thompson SG: Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med 2002; 21:1539–1558Google Scholar

24. Deeks J, Altman D, Bradburn M: Statistical methods for examining heterogeneity and combining results from several studies in meta-analysis, in Systematic Reviews in Health Care: Meta-Analysis in Context, 2nd ed. Edited by Egger M, Davey-Smith G, Altman D. London, BMJ Publishing Group, 2001, pp 285–312Google Scholar

25. Shelton RC, Williamson DJ, Corya SA, Sanger TM, Van Campen LE, Case M, Briggs SD, Tollefson GD: Olanzapine/fluoxetine combination for treatment-resistant depression: a controlled study of SSRI and nortriptyline resistance. J Clin Psychiatry 2005; 66:1289–1297Google Scholar

26. Corya SA, Williamson DJ, Sanger TM, Briggs SD, Case M, Tollefson GD: A randomized, double-blind comparison of olanzapine/fluoxetine combination, olanzapine, fluoxetine, and venlafaxine in treatment-resistant depression. Depress Anxiety 2006; 23:364–372Google Scholar

27. Thase M, Corya SA, Osuntokun O, Case M, Henley DB, Sanger TM, Watson SB, Dube S: A randomized, double-blind comparison of olanzapine/fluoxetine combination, olanzapine, and fluoxetine in treatment-resistant major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2007; 68:224–236Google Scholar

28. Mahmoud RA, Pandina G, Turkoz I, Kosik-Gonzalez C, Canuso CM, Kujawa MJ, Gharabawi-Garibaldi GM: Risperdione for treatment-refractory major depressive disorder. Ann Intern Med 2007; 147:593–602Google Scholar

29. Reeves H, Batra S, May RS, Zhang R, Dahl DC, Li X: Efficacy of risperidone augmentation to antidepressant in the management of suicidality in major depressive disorder: a randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled pilot study. J Clin Psychiatry 2008; 69:1228–1336Google Scholar

30. Keitner GI, Garlow SJ, Ryan CE, Ninan PT, Solomon DA, Nemeroff CB, Keller MB: A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of risperidone augmentation for patients with difficult-to-treat unipolar, non-psychotic major depression. J Psychiatr Res 2009; 43:205–214Google Scholar

31. Khullar A, Chokka P, Fullerton D, McKenna S, Blackamn A: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study of quetiapine as augmentation therapy to SSRI/SNRI agents in the treatment of non-psychotic unipolar depression with residual symptoms, in American Psychiatric Association 2006 Annual Meeting: New Research Abstracts (Toronto, Canada, May 20–25, 2006). Washington, DC, APA, 2006Google Scholar

32. Mattingly G, Ilivicky H, Canale J, Anderson R: Quetiapine combination for treatment-resistant depression, in American Psychiatric Association 2006 Annual Meeting: New Research Abstracts (Toronto, Canada, May 20–25, 2006). Washington, DC, APA, 2006Google Scholar

33. McIntyre A, Gendron A, McIntyre A: Quetiapine adjunct to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors or venlafaxine in patients with major depression, comorbid anxiety, and residual depressive symptoms: a randomized, placebo-controlled pilot study. Depress Anxiety 2007; 24:487–494Google Scholar

34. Nierenberg AA, Papakostas GI, Petersen T, Montoya HD, Worthington JJ, Tedlow J, Alpert JE, Fava M: Lithium augmentation of nortriptyline for subjects resistant to multiple antidepressants. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2003; 23:92–95Google Scholar