Association of Depressed Mood and Mortality in Older Adults With and Without Cognitive Impairment in a Prospective Naturalistic Study

Abstract

Objective

The authors examined predictors of mortality in individuals age 50 or older with or without cognitive impairment in a 12-year prospective naturalistic study of subcortical ischemic vascular disease focusing on symptoms of depressed mood, apathy, anhedonia, or anergia.

Method

A total of 498 participants were recruited from the community and from memory clinics into a multicenter longitudinal study of subcortical ischemic vascular disease. For baseline cognitive status, 36% of participants were assessed as cognitively intact, 31% as cognitively impaired, and 33% as demented. All participants underwent a research protocol MRI, and 41% were classified as having subcortical lacunes. Depressed mood, anhedonia, anergia, and apathy were assessed at baseline using a structured behavioral assessment. Cox regression models were used to investigate the associations between neuropsychiatric symptoms and mortality, controlling for age, gender, race, education level, cognitive status, presence of vascular lacunes, and vascular risk factors.

Results

Of 498 participants, 175 (35%) died over the follow-up period, with a median survival time of 5.6 years. In the multivariate analyses, cognitive impairment, age, male gender, depressed mood, and the presence of lacunes predicted higher mortality. Participants with both lacunes and depressed mood had the shortest survival among all cognitive groups. The mortality hazard ratio for participants with depressed mood was 2.2 (95% CI=1.5–3.2) after adjustment for cognitive status, age, gender, education level, race, lacunes, and all vascular conditions.

Conclusions

These findings suggest the importance of detecting depressed mood in individuals with cerebrovascular disease and of developing more aggressive treatment and preventive interventions for this vulnerable population.

Depression in the elderly tends to occur in the context of medical and neurological disorders that may worsen outcomes of medical illness, including mortality rates (1–3). Some studies have linked depressive symptoms and mortality in frail and medically ill elderly persons (4, 5). Other factors associated with mortality include advanced age, gender, socioeconomic status, severity of medical illness, and psychiatric disorders (6). The effects of other neuropsychiatric symptoms on mortality are less well studied (7, 8). A study of a large Japanese community sample (7) found a differential effect of depressive symptoms and symptoms of apathy and anergia on mortality from medical causes (i.e., cerebrovascular versus cardiovascular disease) in older persons. None of these previous studies included direct neuroimaging measures of cerebrovascular disease as predictors of mortality, which is important in understanding whether the presence of cerebrovascular disease mediates depression effects on mortality.

Cerebrovascular and neurodegenerative brain changes commonly accompany late-life neuropsychiatric symptoms and contribute to the underlying pathophysiology and heterogeneity of these disorders. Subcortical ischemic vascular disease characterized by microvascular or small-artery disease is common in cognitively normal older adults and in those with different types of cognitive impairment, including dementia. It is thought to be responsible for a certain pattern of cognitive impairment with predominant executive dysfunction and for the development of depression and other behavioral symptoms (9, 10). MRI can help in early detection of subcortical lacunes and deep white matter changes that might result in cognitive or neuropsychiatric symptoms due to disruption of cortical-subcortical pathways (9, 11, 12) or contribute to mortality because of the extent of cerebrovascular disease.

Geriatric neuropsychiatry has recently experienced a surge of interest in subsyndromal depression and apathy because of their high prevalence, profound effect on health and functional outcomes, and differential management (10, 13–17). Subsyndromal depression is more prevalent than major depression in community-dwelling older adults, with rates estimated at 12%–30%, compared with 2%–5% for major depression (18, 19). Although definitions of subsyndromal depression and apathy have varied among studies, research has repeatedly demonstrated that subsyndromal depressive states are associated with adverse health consequences, including poor quality of life, disability, and mortality (20–22).

The use of MRI may shed light on the neurobiology and neurocircuitry involved in the mediation of mood and motivational impairment in late life (10, 13, 15, 23–25) and may define new endophenotypes of subsyndromal depressive states. It may also enhance our understanding of the relationships among subcortical ischemic vascular disease, depression, and mortality. Neuroanatomical abnormalities that have been consistently identified in patients with late-life major depression, and more recently with late-life apathy, include smaller brain volumes and larger volumes of high-intensity lesions in subcortical gray and white matter (13, 15). Structural atrophy has been reported in the prefrontal cortex (26) and hippocampus (27, 28). Historically, neuroimaging studies of stroke have focused on lesion-behavior relationships (29, 30). We previously reported the association between lacunar volume and the presence of apathy, anhedonia, anergia, and depression (10).

Our objectives in this study were to examine the independent and cumulative effects of the neuropsychiatric symptoms of depressed mood, apathy, anergia, and anhedonia on mortality in a large cohort of older individuals with and without subcortical ischemic vascular disease and with and without cognitive impairment in a prospective naturalistic follow-up study. We chose to focus on these four symptoms because of their higher prevalence in subcortical ischemic disease and their overlapping features, which frequently lead to misdiagnosis and mismanagement. We hypothesized that cognitive status, older age, male gender, depressed mood, lacunes, and cardiovascular disease would independently contribute to mortality risk. No prior studies have attempted to differentiate the predictors of mortality using symptoms of depressed mood, apathy, anergia, and anhedonia as well as MRI-identified lacunes in the same clinical sample, which is important in identifying independent contributions of cerebrovascular disease and behavioral symptoms to mortality.

Method

Participants

Participants were recruited into the Ischemic Vascular Dementia Program Project, a multicenter longitudinal study examining the contributions of subcortical ischemic vascular disease to cognitive impairment and dementia. Recruitment categories were intended to provide a spectrum of cognitive function (cognitively intact, cognitively impaired, and demented), with cognitive impairment due to either Alzheimer's disease or subcortical vascular disease. Four clinical sites from three academic dementia centers participated. Participants were patients who presented at memory clinics seeking evaluation for cognitive problems or were found to have subcortical cerebrovascular disease, or cognitively normal individuals recruited from the community. Exclusion criteria at time of enrollment included age under 50 years, nonfluency in English, cortical strokes, and severe illnesses (other than cerebrovascular disease or dementia) or medications likely to affect cognition. In this study, we analyzed data on 498 participants who were followed for up to 12 years as of April 2008.

Participants received a comprehensive clinical evaluation that included a detailed medical and neurological history and examination, laboratory tests, and neuropsychiatric assessment of behavioral and psychological symptoms. Cognition was evaluated using a battery of neuropsychological tests, which have been described elsewhere (31, 32). Diagnoses were made at a multidisciplinary case conference; dementia was diagnosed by DSM-IV criteria (33). Participants who had cognitive impairment not severe enough to meet criteria for dementia or who evidenced no functional impairment were diagnosed as having cognitive impairment without dementia. Demented participants were further clinically diagnosed using the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association diagnostic criteria for Alzheimer's disease and California Alzheimer's Disease Diagnostic and Treatment Center criteria for ischemic vascular dementia (34). The presence and severity of comorbid cardiovascular conditions (current and past) were assessed using a standard instrument and physical examination. The institutional review boards at all participating institutions approved the study, and all participants or their representatives gave written informed consent to participate in the study.

Neuropsychiatric Assessment

Behavioral ratings were based on clinician ratings using the Psychiatric Evaluation section of the Minimum Uniform Data Set (MUDS) of the California Alzheimer's Disease Centers Program administered at baseline. Central training on uniform administration of the MUDS was provided as part of the Alzheimer's Disease Centers Program (35). Symptom ratings were made separately for depressed mood, apathy, anhedonia, and anergia as follows: 0=not present; 1=questionable; 2=present but mild at subthreshold or subsyndromal level; 3=present and severe at threshold or syndromal level; and 4=not determined. The assessment of each of these symptoms was based on patient and caregiver reports and direct clinical examination. In our analyses, we combined both syndromal and subsyndromal neuropsychiatric symptoms to reflect clinically significant psychopathology with comparable effect on functional impairment (18). The reference group consisted of participants whose symptoms were rated as "not present" or "questionable." Individuals with symptoms rated as "not determined" were excluded from our analyses (the numbers excluded on this basis were 26 for depressed mood, 26 for anhedonia, 24 for anergia, and 25 for apathy). A total of 498 participants had symptom ratings and were included in the analyses.

MRI Methods

The MR image acquisition and segmentation methods used in this study have been previously reported (10, 36, 37). The MRI variable used in this analysis was the presence or absence of lacunes. The presence of lacunes was determined by the expert radiologist and neurologist who reviewed all MRI scans. Subcortical lacunes were defined as small (>2 mm) areas of the brain with increased signal relative to CSF on proton density MRI in subcortical gray and white matter seen in axial slices at the level of the basal ganglia and thalamus. Lacunes were differentiated from perivascular spaces, which can be particularly prominent below the anterior commissure and putamen and at bends in the course of penetrating arterioles. When appearing in white matter, lacunes were differentiated from white-matter hyperintensities by an isointense signal to CSF and lesion size ranging from 3 mm to 15 mm. To differentiate lacunes in the white matter and white-matter hyperintensities, only cystic lacunes were included. In the subcortical gray matter, a more liberal definition was used for lacunes—discrete hyperintensities >2 mm in diameter on proton density images.

Data Analysis

Deceased and surviving participants were initially compared on all demographic and clinical variables using t tests and chi-square tests, as appropriate. Unadjusted and multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to evaluate the association of clinically significant neuropsychiatric symptoms of depressed mood, apathy, anhedonia, and anergia with mortality. For these models, follow-up time for all participants began at entry into the study cohort. Follow-up ended at the last study visit attended for surviving participants and at the date of death for deceased participants. Associations between neuropsychiatric symptoms and other independent variables and mortality were summarized as hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Each neuropsychiatric variable was fitted in the regression models separately. Because overlap between the neuropsychiatric variables averaged about 40%, we also computed a summary global behavioral measure of neuropsychiatric symptoms for each participant. This summary variable was the total number of neuropsychiatric symptoms (depressed mood, apathy, anhedonia, and anergia) rated as present and thus ranged from 0 to 4.

Because our major hypotheses related to the associations of the neuropsychiatric symptoms to mortality, our multivariate Cox regression modeling took the following approach. In multivariate model 1, we adjusted each neuropsychiatric symptom for cognitive group (cognitively intact, cognitively impaired, or demented), age, gender, education level, and ethnicity. The presence of lacunes was added in a subsequent model (adjusted model 2). The reference groups for gender, ethnicity, cognitive group, and lacunes were male, white, cognitively intact, and "no lacunes," respectively. To determine whether the observed associations might be confounded by comorbid vascular disease, we subsequently added vascular conditions (separate indicator variables for a history of stroke, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, arrhythmia, congestive heart failure, myocardial infarction, and coronary artery bypass graft surgery) to adjusted model 3. To take into account the multiple hypothesis testing in light of the fact that this was an exploratory analysis, we used a conservative two-sided alpha level of 0.01 for the main exposure variables (neuropsychiatric symptoms) in the final multivariate models. The assumption of constant proportional hazards over the follow-up period was met for each independent variable.

To graphically illustrate the associations between depressed mood and mortality, we plotted the survival curve estimates from the final proportional hazards model by cognitive group and depressed mood status and by lacunes (present/absent) and depressed mood status.

Results

Of the 498 individuals who participated in the study, 250 (50.2%) were men; 365 (73.3%) were Caucasian, 23 (4.6%) were Hispanic, 30 (6.0%) were African American, 78 (15.7%) were Asian, and 2 (2.4%) were other. The mean age at baseline was 74.5 years (range=52.7–94.7 years). A total of 175 participants (35%) died over the course of follow-up.

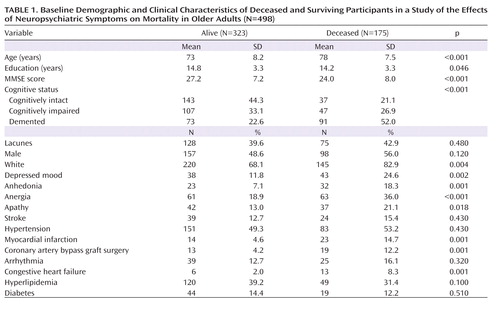

The baseline clinical diagnoses of demented participants (N=164) included possible or probable ischemic vascular dementia (N=36; 22%), mixed Alzheimer's disease and vascular disease (N=33; 20%), possible or probable Alzheimer's disease (N=87; 53%), cerebrovascular disease not meeting criteria for ischemic vascular dementia (N=4; 2%), and other (N=4; 2%). Clinical diagnoses of dementia were not used in the analyses reported here. Demographic characteristics and global cognitive status (measured by the Mini-Mental State Examination) are presented by vital status (alive or deceased during follow-up) in Table 1.

|

Table 1 compares the deceased and surviving participants on variables of interest. Among all participants evaluated at baseline, 180 (36%) were cognitively intact, 154 (31%) were cognitively impaired without dementia, and 164 (33%) were diagnosed with dementia; 203 (41%) participants were determined to have lacunes on MRI. The median follow-up time for all participants was 4.7 years (range=0.01–12.9 years). Among deceased participants, the median follow-up (time to death) was 4.6 years (range: 0.3–12.0).

In the entire sample, 81 participants (16.2%) had clinically significant depressed mood, 55 (11.1%) were considered to have clinically significant (i.e., syndromal and subsyndromal) levels of anhedonia, 124 (24.9%) had anergia, and 79 (15.8%) had apathy. Despite the close clinical characteristics of these symptoms, the overlap between them was moderate, with 39.5% between anergia and depressed mood, 69.1% between depressed mood and anhedonia, and 42% between depressed mood and apathy (all p values <0.0001). Given some overlap among symptoms, we also conducted an analysis with the composite behavioral measure that took into account coexisting symptoms, as explained in the Method section.

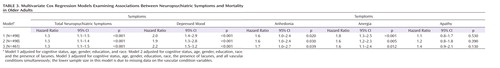

Table 2 presents the results of the unadjusted Cox regression models. The mortality risk was significantly elevated with older age, lower education levels, male gender, and cognitive impairment and dementia. Participants with lacunes noted on baseline MRIs had significantly higher mortality. Vascular conditions associated with higher mortality in this cohort included hypertension, myocardial infarction, coronary artery bypass graft surgery, arrhythmias, and congestive heart failure. The presence of each of the four neuropsychiatric symptoms was significantly associated with elevated mortality in unadjusted analyses, with hazard ratios ranging from 2.3 to 3.1. In addition, the summary score of all neuropsychiatric symptoms combined was associated with a mortality hazard ratio of 1.5 (per symptom present; 95% CI=1.4–1.7).

|

Table 3 presents the results of the multivariate Cox regression models detailing the adjusted associations of neuropsychiatric symptoms with mortality. Each neuropsychiatric symptom was modeled separately (i.e., symptoms were not adjusted for one another). All models were adjusted for cognitive status, age, male gender, education level, and race. Models were successively adjusted for the presence of lacunes and comorbid vascular disorders. The summary measures of total neuropsychiatric symptoms, depressed mood, and anergia each remained significantly associated with mortality after adjustment for cognitive status, age, male gender, education level, and race (adjusted model 1). Except for a decrease in the anergia hazard ratio, further adjustment for the presence of lacunes did not alter these results. Using a 10% rule for the change in hazard ratios to define the presence of a confounder, the comorbid vascular conditions were not meaningful confounders for the association between the summary measure of total neuropsychiatric symptoms and mortality (adjusted model 3). Although anhedonia, anergia, and apathy were associated with an increased risk of mortality after adjustment for demographic and vascular conditions (using α=0.01), these associations fell short of statistical significance.

|

When demographic characteristics, the presence of lacunes, and all comorbid vascular conditions were taken into account, the summary measure of total neuropsychiatric symptoms and depressed mood remained significantly positively associated with mortality (Table 3, model 3). In the fully adjusted depressed mood model, cognition remained independently associated with mortality (cognitive impairment hazard ratio=2.2, 95% CI=1.3–3.8; dementia hazard ratio=4.7, 95% CI=2.9–7.5), while the presence of lacunes was of marginal significance (hazard ratio=1.4, 95% CI=1.0–2.1). We evaluated whether our finding relating depressed mood to mortality was driven by the presence of syndromal versus subsyndromal depressed mood by including separate indicator variables for each in our multivariate model. Both depressed mood indicators yielded elevated hazard ratios (for subsyndromal depressed mood, hazard ratio=1.7; for syndromal depressed mood, hazard ratio=2.2). These hazard ratios did not significantly differ from one another, providing further support for combining the two into one category of depressed mood.

Figures 1 and 2 present the adjusted cumulative survival curves by cognitive group and depressed mood, and the presence of lacunes and depressed mood. Within each cognitive group, survival was lower among participants with depressed mood (Figure 1). Depressed mood was also associated with reduced survival in participants with and without lacunes (Figure 2). The association of depressed mood with mortality did not significantly differ by cognitive group or the presence of lacunes.

Discussion

This study is the first to report the effects of four common neuropsychiatric symptoms, comorbid vascular conditions, and subcortical ischemic vascular disease on mortality in a unique large cohort of individuals over age 50 with and without cognitive impairment. We found that depressed mood was significantly associated with elevated mortality risk after adjustment for age, gender, education level, race, cognitive status, and the presence of lacunes, as well as multiple vascular risk factors. Other significant correlates of mortality included cognitive status, older age, lower education level, male gender, and cerebrovascular lacunes. Hypertension, congestive heart failure, history of myocardial infarction, arrhythmia, and coronary artery bypass graft surgery were significantly associated with mortality in the unadjusted analyses. Race and other comorbid medical conditions did not predict mortality.

Our findings of the detrimental effect of depressed mood on mortality are consistent with previous reports of clinical depression associated with social, occupational, and physical impairment and suicide and non-suicide-related mortality (1, 38). For example, in some studies psychiatric disorders, particularly depression, have been found to predict mortality in various medical conditions (2, 29, 39). Depression and other psychiatric problems were identified as predictors of mortality in the Baltimore Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study (15-year follow-up) (40).

Among depressed patients, anhedonia and hopelessness have been related to mortality (41, 42). Stroke survivors have a greatly elevated risk for clinically significant depressive symptoms even 2 or more years after the index stroke, independent of functional disability, cerebrovascular risk factors, and prior depressive symptoms (43). Poststroke depression has not been accurately diagnosed and treated, particularly when silent subcortical ischemic infarctions are involved. With the advantage of MRI, researchers should focus investigations on the association of specific cerebral regions with depressive manifestations and treatment response. Methodological issues such as previous history of depression and the type of depressive manifestation should be considered in evaluating specific risk factors for depression and mortality (6).

Depression complicates the outcomes of medical and cognitive diseases. It can cause more severe functional impairment, retard the rehabilitation process, complicate outcomes, and increase mortality risk. It has been hypothesized that depression can lead to worse outcomes for several reasons. First, there may be some direct biological effects, as suggested in cardiovascular data, such as exaggerated platelet aggregation and reduced heart rate variability (44, 45). Second, depression-related symptoms may prevent patients from participating in their medical care. The presence of anhedonia, apathy, hopelessness, or anergia also may lead to behaviors that discourage family members and caregivers from providing necessary assistance, causing delay or even preventing these patients from receiving optimal care. Third, cognitive symptoms affect how depressed patients perceive and interpret clinical information, which can contribute to further stress and increase depressive symptoms (46). There are also complex interactions between depression and cognitive impairment in relation to mortality. Depression rates increase with increasing cognitive impairment, and depression and cognitive impairment can have additive effects on mortality (47). Lastly, the individual symptoms may have an additional deleterious effect because depressed, inactive, withdrawn patients may be susceptible to unexpected complications, such as thromboembolic events and infections (45), or poor long-term outcomes of diabetes (48).

Despite growing evidence regarding the negative impact of depression on mortality, data have begun to illuminate the effects of apathy, anergia, or anhedonia on mortality (7). In our sample, the presence of depressed mood increased the risk of dying on average by 90%–120%, while anergia and our global behavioral measure of neuropsychiatric symptoms increased the risk of dying on average by 30%–80%, depending on the multivariate model (Table 3). The presence of apathy or anhedonia also increased the risk of dying by 20%–70% but did not reach statistical significance after adjustment for covariates (Table 3). In older adult populations, the deleterious effect of depressive or other neuropsychiatric symptoms may be obscured by a higher expected mortality rate and multiple competing potential causes of death (46, 49). An alternative explanation is "selective survival," where those susceptible to the adverse outcomes of depression died as young adults (42, 50).

As expected, the presence of cognitive impairment or dementia, older age, and male gender were associated with a greater risk of mortality and shorter survival (Table 1 and Figures 1 and 2). This is consistent with other studies reporting on predictors of mortality (51, 52). We found male gender to be a predictor of mortality, which is consistent with other reports of men having greater mortality rates and shorter life spans than women, attributed in part to a greater prevalence of cardiovascular disease (53). Depression and hopelessness in men are associated with increased risks of all-cause and cause-specific mortality (54).

Similar to other elderly cohorts, our participants had multiple comorbid physical illnesses, particularly cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, which can result in depression as a result of their direct effect on the brain or pathophysiology or of existing disability. In fact, we recruited participants on the basis of subcortical ischemic vascular disease and in the absence of cortical strokes, which is unique to our sample compared with previous prospective naturalistic studies of medically ill participants. Survival was consistently shorter among participants with lacunes and/or with depressed mood in all cognitive groups, with the shortest time to death among participants with both lacunes and depressed mood (Figures 1 and 2). Lacunes were associated with an approximate doubling of the mortality risk (Table 2). Future analyses of predictors of mortality could provide more refined estimates of the associations of lacunes with mortality by including lacunar size, number, and localization as independent variables.

As described in Table 2, hypertension, congestive heart failure, history of myocardial infarction, arrhythmia, and coronary artery bypass graft surgery were significantly associated with mortality. This is consistent with existing data on the effects of serious cardiovascular disease on mortality in medically ill populations (55). However, associations of neuropsychiatric symptoms with mortality in this cohort were not altered by adjustment for these vascular factors. Greater depressive symptoms are associated with elevated risks of all-cause and, more specifically, cardiovascular disease mortality in men (56). A large proportion of older women also report levels of depressive symptoms that are significantly related to elevated risks of cardiovascular disease mortality and all-cause mortality, even after controlling for established cardiovascular disease risk factors. Whether early recognition and treatment of subclinical depression will lower cardiovascular disease risk remains to be determined in clinical trials (57).

There are limitations to our study. First, our analyses are based on the symptoms reported by caregivers of patients with dementia, and not patients' reports. We combined participants with major and minor depression, as well as those with and without cognitive impairment. Forty percent of the sample had evidence of cerebrovascular disease as indicated by the presence of lacunes on MRI, which is not outside of the range in older adults with cognitive impairment or psychiatric symptoms (10, 58). Although given the complexity of the operations of multiple clinics and research programs involved in the study, we are not able to estimate the total number of participants screened and excluded, our sample was probably reflective of the population of older adults with comorbid medical and cognitive conditions with cerebrovascular disease who are seen in tertiary referral memory clinics, a group that tends to have higher rates of depressed mood and related neuropsychiatric symptoms.

Our study suggests that early diagnosis of depressed mood as well as other neuropsychiatric symptoms of anergia, apathy, and anhedonia, especially if these are present together, may lead to identification of groups at high risk for early mortality. If present together, cognitive impairment, depressed mood, and subcortical vascular disease increase the risk of mortality. However, we need to improve our understanding of the impact of neuropsychiatric symptoms on morbidity and mortality in individuals with cerebrovascular disease and cognitive impairment in order to develop approaches to the early diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of these significant mortality risk factors. Successful treatment of depression and vascular risk factors is likely to have a positive effect that also applies to rehabilitation, quality of life, and cardiovascular mortality (59). Identifying and modifying key risk factors are crucial to reducing the morbidity and mortality of cerebrovascular disease. Future studies should evaluate the potential use of MRI for early detection of groups at high risk for depression, cognitive impairment, and mortality. Potential intervention targets should include treatment of depression and dementia as well as reduction of vascular risk factors in order to reduce mortality in this vulnerable population.

1 : Clinical and neuroradiologic features associated with chronicity in late-life depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 1999; 7:309–316 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2 : First-incidence anxiety in the Lundby study: course and predictors of outcome. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1998; 98:14–22 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3 : Depression and excess mortality: evidence for a dose response relation in community living elderly. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2009; 24:169–176 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4 : Depressive symptoms and 3-year mortality in older hospitalized medical patients. Ann Intern Med 1999; 130:563–569 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5 : Depressive symptoms and risk of mortality in frail, community-living elderly persons. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2003; 11:561–567 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6 : [Poststroke depression: risk factors and antidepressant treatment]. Rev Assoc Med Bras 2003; 49:450–459 (Portuguese) Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7 : The differential influence of distinct clusters of psychiatric symptoms, as assessed by the General Health Questionnaire, on cause of death in older persons living in a rural community of Japan. J Am Geriatr Soc 2002; 50:313–320 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8 : Self-reported lack of energy (anergia) among elders in a multiethnic community. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2008; 63:707–714 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9 : Neuropathology lessons in vascular dementia. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2005; 19:45–52 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10 : The MRI brain correlates of depressed mood, anhedonia, apathy, and anergia in older adults with and without cognitive impairment or dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2008; 23:1040–1050 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11 : Subcortical ischaemic vascular dementia. Lancet Neurol 2002; 1:426–436 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12 : Antidepressant exposure may protect against decrement in frontal gray matter volumes in geriatric depression. J Clin Psychiatry 2005; 66:964–967 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13 : Neuroanatomical characteristics of geriatric apathy and depression: a magnetic resonance imaging study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2007; 15:386–394 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14 : A SPECT study of apathy in Alzheimer's disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2007; 24:65–72 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15 : Vascular disease and apathy in old age: the Leiden 85-plus study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2008; 23:266–271 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16 : Depressive symptoms in late life: associations with apathy, resilience, and disability vary between young-old and old-old. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2008; 23:238–243 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17 : Beyond the "C" in MCI: noncognitive symptoms in amnestic and non-amnestic mild cognitive impairment. CNS Spectr 2008; 13:66–72 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18 : Clinically significant non-major depression: old concepts, new insights. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2002; 10:239–255 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19 : Subsyndromal symptomatic depression: a new mood disorder? J Clin Psychiatry 1994; 55(suppl):18–28 Medline, Google Scholar

20 : Depression, disability days, and days lost from work in a prospective epidemiologic survey. JAMA 1990; 264:2524–2528 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21 : Toward a threshold for subthreshold depression: an analysis of correlates of depression by severity of symptoms using data from an elderly community sample. Gerontologist 2001; 41:357–365 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22 : The DSM-IV "minor depression" disorder in the oldest-old: prevalence rate, sleep patterns, memory function, and quality of life in elderly people of Italian descent in southern Brazil. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2002; 17:107–116 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23 : Clinically defined vascular depression. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:562–565 Link, Google Scholar

24 : Apathy, anhedonia, and psychomotor retardation in elderly psychiatric patients and healthy elderly individuals. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 2001; 14:11–16 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25 : Is apathy in late-life depressive illness related to age-at-onset, cognitive function, or vascular risk? Int Psychogeriatr 2004; 16:481–486 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26 : Neuroimaging studies of mood disorders. Biol Psychiatry 2000; 48:813–829 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27 : Cingulate function in depression: a potential predictor of treatment response. Neuroreport 1997; 8:1057–1061 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28 : Unmasking disease-specific cerebral blood flow abnormalities: mood challenge in patients with remitted unipolar depression. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159:1830–1840 Link, Google Scholar

29 : Poststroke apathy and regional cerebral blood flow. Stroke 1997; 28:2437–2441 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30 : Apathy and depressed mood in acquired brain damage: relationship to lesion localization and psychophysiological reactivity. Psychol Med 1999; 29:447–456 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31 : MRI predictors of cognition in subcortical ischemic vascular disease and Alzheimer's disease. Neurology 2001; 57:2229–2235 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32 : Executive dysfunction in subcortical ischaemic vascular disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2002; 72:217–220 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33 American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed (DSM-IV). Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994 Google Scholar

34 : Clinical criteria for the diagnosis of vascular dementia: a multicenter study of comparability and interrater reliability. Arch Neurol 2000; 57:191–196 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35 : Caregiver and clinician assessment of behavioral disturbances: the California Dementia Behavior Questionnaire. Int Psychogeriatr 1997; 9:155–174 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36 : Hippocampal and cortical atrophy predict dementia in subcortical ischemic vascular disease. Neurology 2000; 55:1626–1635 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37 : White matter lesions are associated with cortical atrophy more than entorhinal and hippocampal atrophy. Neurobiol Aging 2005; 26:553–559 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38 : Depressive disorders and cerebrovascular disease, in Vascular Disease and Affective Disorders. Edited by Chiu HAmes DKatona C. London, Martin Dunitz, 2001, pp 127–147 Google Scholar

39 : Diagnostic groups and depressed mood as predictors of 22-month mortality in medical inpatients. Psychosom Med 1998; 60:570–577 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40 : Psychopathology and attrition in the Baltimore ECA 15-year follow-up, 1981–1996. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1999; 34:91–98 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41 : Anhedonia and death. Psychol Rep 1978; 43(3 pt 2):1120–1122 Crossref, Google Scholar

42 : Association between depressive symptoms and mortality in medical inpatients. Psychosomatics 2000; 41:426–432 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

43 : Depression after stroke: a prospective epidemiological study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2004; 52:774–778 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

44 : Platelet cytosolic calcium responses to serotonin in depressed patients and controls: relationship to symptomatology and medication. Biol Psychiatry 1998; 43:327–334 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

45 : Exaggerated platelet reactivity in major depression. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:1313–1317 Link, Google Scholar

46 : Depressed mood and survival in seriously ill hospitalized adults: the SUPPORT investigators. Arch Intern Med 1998; 158:397–404 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

47 : Additive effects of cognitive function and depressive symptoms on mortality in elderly community-living adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2003; 58:M461–M467 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

48 : Depression predicts increased incidence of adverse health outcomes in older Mexican Americans with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2003; 26:2822–2828 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

49 : Mortality, symptoms, and functional impairment in late-life depression. J Gen Intern Med 1998; 13:746–752 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

50 : The association between depressive symptoms and mortality among older participants in the Epidemiologic Catchment Area-Piedmont health survey. J Gerontol 1989; 44:S149–S156 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

51 : APOE-related mortality: effect of dementia, cardiovascular disease, and gender. Neurobiol Aging 2009; 30:1545–1551 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

52 : Depression predicts mortality in the young old, but not in the oldest old: results from the Berlin Aging Study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2008; 16:844–852 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

53 : Gender differences in the management and prognosis of myocardial infarction among patients > or = 65 years of age. Am J Cardiol 2008; 101:1531–1536 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

54 : Hopelessness and risk of mortality and incidence of myocardial infarction and cancer. Psychosom Med 1996; 58:113–121 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

55 : Depressed affect, hopelessness, and the risk of ischemic heart disease in a cohort of US adults. Epidemiology 1993; 4:285–294 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

56 : Depressive symptoms and mortality in men: results from the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial. Stroke 2005; 36:98–102 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

57 : Depression and cardiovascular sequelae in postmenopausal women: the Women's Health Initiative (WHI). Arch Intern Med 2004; 164:289–298 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

58 : Effect of infarcts on dementia in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Ann Neurol 2008; 64:168–176 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

59 : [Emotional reactions common sequelae of stroke]. Lakartidningen 2004; 101:2108–2110, 2112–2113, 2115 (Swedish) Medline, Google Scholar