Reducing Suicidal Ideation and Depression in Older Primary Care Patients: 24-Month Outcomes of the PROSPECT Study

Abstract

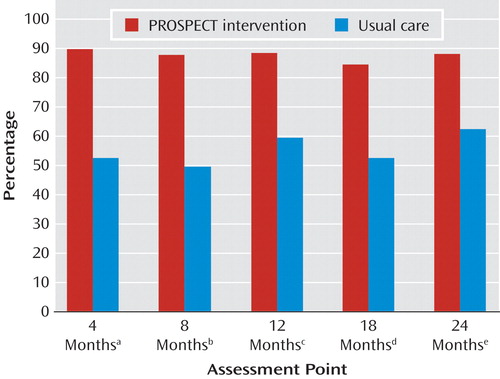

Objective: The Prevention of Suicide in Primary Care Elderly: Collaborative Trial (PROSPECT) evaluated the impact of a care management intervention on suicidal ideation and depression in older primary care patients. This is the first report of outcomes over a 2-year period. Method: Study participants were patients 60 years of age or older (N=599) with major or minor depression selected after screening 9,072 randomly identified patients of 20 primary care practices randomly assigned to provide either the PROSPECT intervention or usual care. The intervention consisted of services of 15 trained care managers, who offered algorithm-based recommendations to physicians and helped patients with treatment adherence over 24 months. Results: Compared with patients receiving usual care, those receiving the intervention had a higher likelihood of receiving antidepressants and/or psychotherapy (84.9%–89% versus 49%–62%) and had a 2.2 times greater decline in suicidal ideation over 24 months. Treatment response occurred earlier on average in the intervention group and increased from months 18 to 24, while no appreciable increase in treatment response occurred in the usual care group during the same period. Among patients with major depression, a greater number achieved remission in the intervention group than in the usual-care group at 4 months (26.6% versus 15.2%), 8 months (36% versus 22.5%), and 24 months (45.4% versus 31.5%). Patients with minor depression had favorable outcomes regardless of treatment assignment. Conclusions: Sustained collaborative care maintains high utilization of depression treatment, reduces suicidal ideation, and improves the outcomes of major depression over 2 years.

The Institute of Medicine has identified prevention of suicide as a national imperative (1) . Despite a recent decline in suicides among persons over age 64, the suicide rate of older adults (14.3 per 100,000) remains higher than that of the general population (2) . Suicidal ideation and depression are two major risk factors for late-life suicide and are targets for prevention (3) .

Primary care is a strategic setting for treating geriatric depression and for preventing suicide. Some 6%–9% of primary care patients have major depression, and more than 17% have less severe depressive symptoms (4) . Among primary care patients with major depression, 18% have suicidal ideation (5) .

Care management models offered over 1 year have been shown to increase utilization of treatment for depression and to improve outcomes of depression in primary care patients (6 , 7) . Depression in old age is a chronic, relapsing illness, and 1-year data alone are insufficient for understanding the impact of care management.

In this report, we present outcomes of a 2-year intervention by the Prevention of Suicide in Primary Care Elderly: Collaborative Trial (PROSPECT). An early analysis (6) showed greater declines in suicidal ideation and depressive symptoms and higher rates of response and remission in depressed patients receiving the PROSPECT intervention than in those receiving usual care. However, by 12 months, the advantages of intervention were no longer retained.

This article focuses on PROSPECT’s primary outcomes during the second year of treatment. We test the hypotheses that depressed patients treated in practices offering the PROSPECT intervention have a greater reduction in suicidal ideation and that they have better depression outcomes—that is, a greater decline in depressive symptoms and higher rates of treatment response and remission—than patients treated in practices delivering usual care over 2 years.

Method

The study was conducted in 20 primary care practices in urban, suburban, and rural areas. Its procedures were approved by the institutional review boards of participating centers (Cornell University, University of Pennsylvania, and University of Pittsburgh). The study used a two-stage random sampling design to produce an age-stratified (60–74 years, >74 years) sample of patients with pending appointments with their physicians (6) .

Randomization

Practices were organized into 10 pairs that were each similar in academic affiliation, size, setting, patient population, and region. The practices of each pair were randomly assigned to use the PROSPECT intervention or to provide usual care. Randomization was done by practice in order to minimize contamination of usual care by intervention procedures.

Intervention

The intervention was offered for 24 months to patients who presented at baseline with a major depression, defined according to DSM-IV criteria, or a minor depression, defined as three to four depressive symptoms, a score of 10 or higher on the 24-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) (8) , and a duration of at least 1 month. The intervention, which has been described in detail elsewhere (6) , was a composite intervention implemented by 15 practice-based care managers guided by a treatment algorithm. The care managers were social workers, nurses, and psychologists trained in PROSPECT procedures. They helped physicians recognize depression, offered algorithm-based recommendations, monitored depressive symptoms and medication side effects, and provided follow-up over 24 months. They also offered interpersonal psychotherapy to patients who declined medication. They saw patients at the practices’ offices but made house calls to patients who were unable to travel, and they addressed patient concerns related to treatment adherence.

The algorithm was based on Agency for Health Care Policy and Research Practice Guidelines, modified for use in elderly patients (9) . The first step of the algorithm was use of citalopram at the target daily dose of 30 mg to avoid undertreatment. Physicians had the option of prescribing other antidepressants or referring patients for psychotherapy other than interpersonal psychotherapy. Research funds covered the cost of citalopram and interpersonal psychotherapy only. Psychiatrist investigators provided weekly group supervision to care managers and were available by telephone.

Usual Care

Physicians in the usual-care practices had no assistance but received videotaped and printed material on geriatric depression and its treatment. They were also informed by letter of the patients’ depression diagnosis and, when present, suicidal ideation.

Systematic Assessment

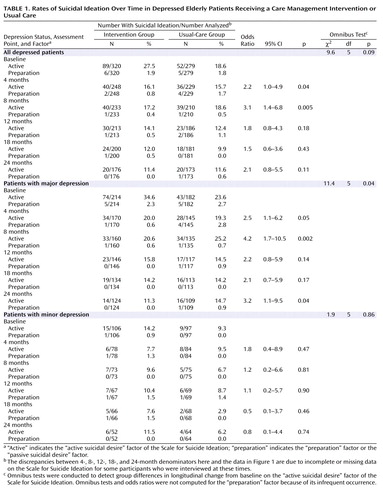

Diagnoses were based on the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (10) . Severity of depression was assessed with the HAM-D and cognitive impairment with the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) (11) . Suicidal ideation was rated with the Scale for Suicide Ideation (12) , which has sound psychometric properties in younger psychiatric outpatients and has yielded a factor structure for older adults similar to that for younger adults (13) . Because scores on the Scale for Suicide Ideation were skewed, with 80%–90% of patients having a score of 0 (indicating no suicidal ideation) at any assessment point, the score on this instrument was treated as a dichotomous variable. We also created dichotomous variables of the three factors of the Scale for Suicide Ideation (12) . The “passive suicidal desire” factor consists of items reflecting precautions to save life, self-confidence in ability to commit suicide, and hesitance to reveal suicidal thoughts. The “active suicidal desire” factor consists of the following items: wish to live, wish to die, reasons for living/dying, wish to make suicide attempt, duration of suicide ideation/wish, frequency of suicide wish, attitude toward suicidal ideation/wish, deterrents to active attempt, reason for contemplating attempt, and expectancy/anticipation of actual attempt. The “preparation” factor consists of items reflecting consideration of method, availability of method, and actualization of attempt. Each participant was assigned to one of the scale’s factors according to severity as follows: participants who endorsed a preparation item were assigned to the preparation factor regardless of whether they endorsed items of other factors. Those who endorsed an active suicidal desire item but not a preparation item were assigned to the active suicidal desire factor. Finally, those who endorsed a passive suicidal desire item but not a preparation or active suicidal desire item were assigned to the passive suicidal desire factor.

Randomization by practice prevented blinded assessment. Nonetheless, raters did not participate in the patients’ treatment and were held to high standards of interrater reliability, as has been reported elsewhere (6) . Assessment data were not made available to care managers or clinicians except as required for safety. Patients had in-person interviews at 12 and 24 months and telephone assessments at 4, 8, and 18 months.

Data Analysis

Tests and estimates of differences in intent-to-treat outcomes were based on longitudinal models with random effects for clustering by patient, practice, and practice pairs. The intent-to-treat sample included all patients who had a baseline assessment regardless of treatment and dropout status during the follow-up period. Clustering by practice and pairs of practices was negligible and did not affect the analysis. The longitudinal random-effects models included main effect and interaction terms that represented intent-to-treat contrasts at each of the 4-, 8-, 12-, 18-, and 24-month assessment points. The “omnibus” statistic is used to test for significant intent-to-treat contrasts at any one follow-up assessment and is a time-by-group interaction (14) . For continuous outcomes, analyses were based on SAS PROC MIXED. Both PROC NLMIXED and the GLIMMIX macro in SAS were used to employ two- and three-level random-effects models, respectively, for binary outcomes. Given a group difference in baseline suicidal ideation (20% versus 31%, p=0.02), this variable was controlled for in all intent-to-treat analyses. Such adjustment is appropriate under the random-effects models. Moreover, all intent-to-treat analyses, except that of the longitudinal suicidal ideation outcome, were robust to such an adjustment. Results were also robust with respect to random-effects assumptions (15) . Additional robustness existed in intervention differences in missed assessments and dropout, without making imputation assumptions, such as last observation carried forward (16) .

Results

Participant Characteristics, Dropout, and Missed Assessments

The participants’ demographic and clinical characteristics have been reported in more detail elsewhere (6) . Overall, 71.6% of participants were women, 30.1% were age 75 or older, 32.4% belonged to minority groups, 3.8% met poverty status, 36.9% were married, and 56.5% lived alone. Their mean HAM-D score was 18.1, and their mean MMSE score was 27.4. There were no significant differences in demographic or clinical characteristics between the intervention and usual-care patient groups except in suicidal ideation.

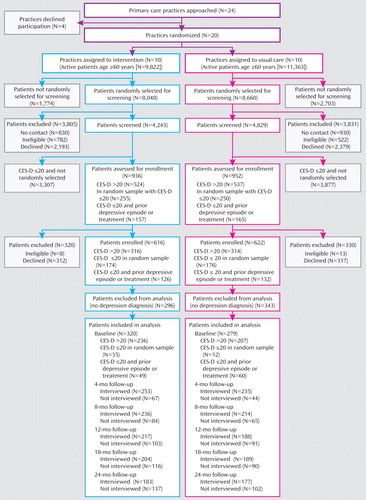

At the 24-month follow-up, 43% (137/320) of patients in the intervention group and 37% (102/279) of those in the usual-care group did not have a research assessment ( Figure 1 ). The influence of differences in dropout was assessed by comparing results from our analysis with results under the shared-parameter model, which adjusts for such differences. Group assignment did not differ by more than 5%, and differences were not statistically significant. The proportion of missed assessments in the usual-care group exceeded that in the intervention group for all assessments, with the difference not exceeding 6 percentage points for any assessment. There were no statistically significant differences between those in the intervention and usual-care groups who had the 24-month assessment.

a CES-D=Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale.

Treatment

More patients in the intervention group (84.9%–89%) than in the usual-care group (49%–62%) received treatment for depression at 4, 8, 12, 18, and 24 months ( Figure 2 ), including antidepressants (p<0.001) and psychotherapy (p<0.001). There were no significant group differences in combination therapy received at 4, 8, 18, and 24 months, but fewer patients in the intervention group received combined treatment at 12 months (odds ratio=0.25, 95% CI=0.07–0.89; χ 2 =4.62, p<0.03).

a Odds ratio=7.8, 95% CI=4.9–12.6, χ 2 =72.3, p<0.0001.

b Odds ratio=7.1, 95% CI=4.0–12.6, χ 2 =45.4, p<0.0001.

c Odds ratio=8.5, 95% CI=4.7–15.4, χ 2 =51.0, p<0.0001.

d Odds ratio=6.8, 95% CI=3.7–12.6, χ 2 =37.8, p<0.0001.

e Odds ratio=8.2, 95% CI=4.5–15.2, χ 2 =45.9, p<0.0001.

Suicidal Ideation, Suicide Attempts, Suicide, and Mortality

At baseline, patients in the intervention group were more likely than those in the usual-care group to report suicidal ideation, that is, to endorse any item on the Scale for Suicide Ideation (29.7% [95/320], compared with 20.4% [57/279], respectively; p<0.01). By month 4, the overall rate of suicidal ideation declined more among patients in the intervention group than in the usual-care group (a decline of 12.8%, to a rate of 16.9% [42/248], compared with a decline of 3.0%, to a rate of 17.4% [40/229], respectively; p=0.02). By month 24, the decline from baseline in the overall rate of suicidal ideation was 2.2 times greater in the intervention group than in the usual-care group (a decline of 18.3%, to a rate of 11.4% [20/176], compared with a decline of 8.3%, to a rate of 12.1% [21/173], respectively), although the difference was not statistically significant.

Ninety percent of patients with a positive score on the Scale for Suicide Ideation at any point over the 24-month follow-up period endorsed only items in the “active suicide desire” factor of the scale. Therefore, further analysis was focused on this factor ( Table 1 ). Adjusting for baseline difference, the omnibus trend testing intent-to-treat differences in change of “active suicidal desire” over time showed a nonsignificant trend favoring the intervention in the whole depressed group (p=0.09) and a significant difference among patients with major depression (p=0.04). Patients with major depression in the intervention group had a lower level of “active suicidal desire” than those in the usual-care group at 4, 8, and 24 months. The differences among patients with minor depression were not significant. Because of low frequencies, combined rates are presented for the other two factors of the Scale for Suicide Ideation (preparation and passive suicidal desire) ( Table 1 ). Meaningful statistical analysis could not be conducted because of insufficient numbers of participants with either of these two factors.

Of all patients with positive responses on the Scale for Suicide Ideation, the most frequently endorsed items were wish to die (item 2, 31%), reasons for living/dying (item 3, 29%), and wish to live (item 1, 15%). While these items fall within the “active suicidal desire” factor, clinicians may classify them as “passive suicidal ideation.” The next most frequently endorsed items were reason for contemplating attempt (item 11, 3.2%), frequency of suicide wish (item 7, 3%), wish to make suicide attempt (item 4, 2.7%), and consideration of method (item 12, 2.4%). For each remaining item, endorsement did not exceed 2%.

During the study, two patients in the intervention arm and three in the usual-care arm attempted suicide. One of the attempted suicides in the intervention arm resulted in death. Further information on mortality was obtained through death certificates over a period of 5 years after study entry. During this time, 60 patients (44.7/1000 person-years) from the intervention arm and 55 (49.7/1000 person-years) from the usual-care arm died (17) . It is possible that some of the deaths after the 24-month follow-up period were due to suicide that was not recorded in death certificates.

Course of Depression

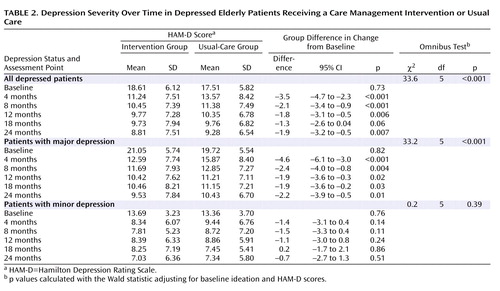

Severity of depression

The decrease in HAM-D score from baseline was greater in the intervention group than in the usual-care group at all assessment points, and the overall omnibus test indicated significance ( Table 2 ). A greater decline in HAM-D score was also observed in patients with major depression at each assessment point and overall. There were no significant differences in decline in HAM-D score between patients in the intervention and usual-care groups with minor depression.

Treatment response

Response was defined as a reduction of baseline HAM-D score by 50% or more. Patients in the intervention group had higher response rates than those in the usual-care group overall (omnibus trend χ 2 =17.3, df=5, p<0.004) as well as at 4, 8, 12, and 24 months. From month 18 to month 24, 7.3 times more patients in the intervention group (9.4%, from 52.9% to 62.3%) responded to treatment than in the usual-care group (1.3%, from 45% to 46.3%). At month 24, 35% more patients in the intervention group had met criteria for response than in the usual-care group. The number needed to treat for response rates at 24 months was six patients; that is, the intervention yielded one additional response for every sixth patient. In the subgroup with major depression, patients in the intervention group had higher response rates than those in the usual-care group overall (omnibus trend χ 2 =17.3, df=5, p<0.004) and at month 4 (odds ratio=3.8, 95% CI=1.8–8.2, p<0.001), month 8 (odds ratio=2.9, 95% CI=1.4–6.2, p<0.005), and month 24 (odds ratio=4.9, 95% CI=2.2–11.2, p<0.001). There was a 9.4% increase in response rate from month 18 to month 24 in patients with major depression in the intervention group (from 54.4% to 63.8%) but a 3.2% decline (from 42.4% to 39.6%) in patients in the usual-care group. The number needed to treat for response rates at 24 months was four patients. There were no significant differences in response rates between patients in the intervention and usual-care groups with minor depression.

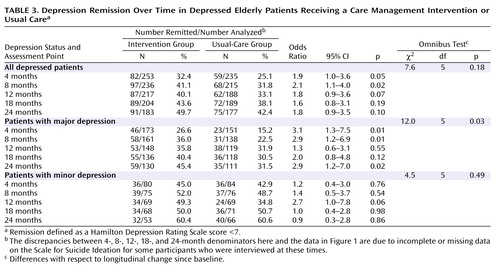

Remission

Remission was defined as a HAM-D score below 7. Among all depressed patients, those in the intervention group had higher remission rates than those in the usual-care group at 4 and 8 months ( Table 3 ). Remission rates among patients in the usual-care group approximated those of patients in the intervention group at 12, 18, and 24 months. Among patients with major depression, those in the intervention group had higher remission rates at 4, 8, and 24 months, but there were no significant differences between groups at 12 and 18 months. At 24 months, 1.44 times more patients in the intervention group had achieved remission than in the usual-care group (45.4% versus 31.5%). The number needed to treat indicated that the intervention yielded one additional remission for every seventh patient. There were no differences in remission rates between patients with minor depression in the intervention and usual-care groups.

Discussion

The principal finding of this study is that depressed patients in the practices that were randomly assigned to use the PROSPECT intervention had a higher likelihood of receiving treatment for depression, a greater decline in suicidal ideation, lower severity of depressive symptoms, and a higher response rate over 24 months than patients in practices providing usual care. At any assessment point, 84.9%–89% of patients in the intervention group received antidepressants and/or psychotherapy, while only 49%–62% of patients in the usual-care group were treated for depression. The intervention was most effective in reducing suicidal ideation among patients with major depression. The decline was sharpest in the first 4 months, and suicidal ideation remained low up to 24 months. Similarly, severity of depression remained lower in patients in the intervention group than in the usual-care group throughout the 24 months. Among patients with major depression, a greater number achieved remission in the intervention than the usual-care group at 4, 8, and 24 months. The intervention had no advantages among patients with minor depression.

To our knowledge, this is the first study of depression care management focusing on suicidal ideation and depressive psychopathology in older primary care patients over a 24-month period. Its findings are consistent with observations in mixed-aged primary care patients (18) , including an intervention of 24 months duration (19) . In geriatric patients, the Improving Mood–Promoting Access to Collaborative Treatment (IMPACT) study provided access to a depression care manager for up to 12 months (20) . Primary care patients receiving the IMPACT intervention were more likely to receive treatment for depression than patients receiving usual care and had better depression outcomes. The advantage over usual care was retained 12 months after the end of the intervention, although there was a decline in response and remission rates from month 12 to month 24 (21) . In contrast, with continuing depression care management the response and remission rates in the intervention arm of the PROSPECT study remained high or increased.

In most participants, suicidal ideation was passive, as is often the case in depressed primary care patients (22) . Even passive suicidal ideation requires attention and treatment. Depressed elders with passive suicidal ideation are more likely to have a history of suicide attempts, higher scores on hopelessness (23) , slower treatment response, and lower rates of response than nonsuicidal elders with major depression (24) . Passive suicidal ideation has a stronger association with medical comorbidity and service utilization than active suicidal ideation or no suicidal ideation (5) . Finally, 35% of patients with suicidal ideation change ideation status during the index episode; patients with passive ideation develop active ideation, and patients with active ideation shift to passive ideation (23) . Change over time in passive suicidal ideation requires further research to identify treatment-responsive and treatment-resistant components that may further focus suicide prevention interventions for depressed older primary care patients.

There were two suicide attempts in the intervention group (one of them completed) and three in the usual-care group. These numbers do not allow statistical study of the relationship of suicidal ideation to suicide or attempts, but they underscore the challenge of reducing the risk of suicide in primary care settings. The relationship of reduction in the rate of suicidal ideation, and especially passive or death ideation, to suicide remains to be determined.

Over the 24-month study period, 49.7% of depressed patients in the intervention group achieved remission (HAM-D score <7). Remission, defined as an almost asymptomatic state, is the optimal outcome because it is associated with a low relapse rate and high functioning (25) . Randomized acute antidepressant trials have shown that 30%–40% of patients achieve remission (26) . A controlled maintenance treatment trial found that 65% of elderly patients with major depression remained in remission over 24 months while treated with paroxetine and monthly psychotherapy (27) . The remission rate of the PROSPECT intervention was somewhat lower than this figure. Nonetheless, demonstrating that a care management intervention can maintain almost half of depressed primary care patients in remission is evidence of a meaningful level of effectiveness.

While antidepressant prescriptions have been rising, many depressed primary care patients receive no treatment for depression (19) . Poor treatment adherence further compromises their care (28) . In this study, more than 84% of patients in the intervention group received antidepressants or psychotherapy throughout the study, while only 49%–62% of those in the usual-care group received any treatment for depression.

Depression almost doubles the risk of death in community samples (29) . Patients with major depression who received the PROSPECT intervention had a lower mortality rate than those who received usual care (adjusted hazard ratio=0.55, 95% CI=0.36–0.84) over a median follow-up period of 52.8 months (17) , but there were no differences in mortality among patients with minor depression. This observation is consistent with reduced all-cause mortality reported in patients receiving antidepressants over 40 months in the Enhancing Recovery in Coronary Heart Disease Patients (ENRICHD) study (30) .

The benefits of the PROSPECT intervention on suicidal ideation and on depression were limited to patients with major depression. Patients with minor depression had overall favorable outcomes regardless of treatment assignment. At 24 months, only 6.2% of patients in the usual-care group had any suicidal ideation and 60.6% had achieved remission of minor depression. Given limited resources, patients with major depression should be the target of a care management intervention.

Limitations of the study include the use of Scale for Suicide Ideation as the sole method for ascertaining suicidal ideation, the lack of information on participants’ discrete medical problems, and the lack of information on specific treatments for depression received by each group. Randomization at the practice level compromised the ability to using blind rating. Covering the cost of citalopram and interpersonal psychotherapy limits the study of cost as a barrier to treatment. Finally, attrition was relatively high, perhaps because the study enrolled a probability sample consisting of patients less interested in study participation than in help-seeking. Nonetheless, probability sampling permits safer generalization of findings. Moreover, the baseline clinical characteristics of those assessed at 24 months were similar to those of the sample assessed at baseline. Finally, taking dropout into consideration did not affect differences between treatment groups significantly. Another limitation is that suicidal ideation was assessed at single points in time, whereas suicidal thoughts wax and wane.

Strengths of this study include its random sampling and a sensitive screening approach designed to identify most patients with depression. These procedures allow generalization of findings to whole practices. Furthermore, the practices were heterogeneous, consisting of small, large, inner-city, rural, academic, and privately owned practices. Finally, patients with suicidal ideation, cognitive impairment, and medical burden were included in the sample. Therefore, these findings may be relevant to real-world practices.

The primary care setting is a strategic point from which to fight suicidality and depression since most elderly patients suffering from these syndromes are treated by primary care physicians. Sustained collaborative care maintains high utilization of depression treatment, reduces suicidal ideation, and increases response and remission rates in major depression over a period of 2 years. Rising response and remission rates between months 18 and 24 underscore the value of long-term care. These observations suggest that sustained collaborative care increases depression-free days and perhaps longevity.

1. Goldsmith SK: Reducing Suicide: A National Imperative. Washington, DC, National Academies Press, 2002Google Scholar

2. Conwell Y, Thompson C: Suicidal behavior in elders. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2008; 31:333–356Google Scholar

3. Conwell Y, Duberstein PR, Cox C, Herrmann JH, Forbes NT, Caine ED: Relationships of age and axis I diagnoses in victims of completed suicide: a psychological autopsy study. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:1001–1008Google Scholar

4. Lyness JM, Caine ED, King DA, Cox C, Yoediono Z: Psychiatric disorders in older primary care patients. J Gen Intern Med 1999; 14:249–254Google Scholar

5. Bartels SJ, Coakley E, Oxman TE, Constantino G, Oslin D, Chen H, Zubritsky C, Cheal K, Durai UN, Gallo JJ, Llorente M, Sanchez H: Suicidal and death ideation in older primary care patients with depression, anxiety, and at-risk alcohol use. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2002; 10:417–427Google Scholar

6. Bruce ML, Ten Have TR, Reynolds CF 3rd, Katz II, Schulberg HC, Mulsant BH, Brown GK, McAvay GJ, Pearson JL, Alexopoulos GS: Reducing suicidal ideation and depressive symptoms in depressed older primary care patients: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2004; 291:1081–1091Google Scholar

7. Unutzer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, Williams JW Jr, Hunkeler E, Harpole L, Hoffing M, Della Penna RD, Noël PH, Lin EH, Areán PA, Hegel MT, Tang L, Belin TR, Oishi S, Langston C; IMPACT Investigators (Improving Mood-Promoting Access to Collaborative Treatment): Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2002; 288:2836–2845Google Scholar

8. Hamilton M: A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1960; 23:56–62Google Scholar

9. Mulsant BH, Alexopoulos GS, Reynolds CF 3rd, Katz IR, Abrams R, Oslin D, Schulberg HC; PROSPECT Study Group: Pharmacological Treatment of Depression in Older Primary Care Patients: the PROSPECT algorithm. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2001; 16:585–592Google Scholar

10. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID). Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1995Google Scholar

11. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR: “Mini-Mental State”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975; 12:189–198Google Scholar

12. Beck AT, Kovacs M, Weissman A: Assessment of suicidal intention: the Scale for Suicide Ideation. J Consult Clin Psychol 1979; 47:343–352Google Scholar

13. Witte TK, Joiner TE Jr, Brown GK, Beck AT, Beckman A, Duberstein P, Conwell Y: Factors of suicide ideation and their relation to clinical and other indicators in older adults. J Affect Disord 2006; 94:165–172Google Scholar

14. Ten Have TR, Kunselman AR, Pulkstenis EP, Landis JR: Mixed effects logistic regression models for longitudinal binary response data with informative drop-out. Biometrics 1998; 54:367–383Google Scholar

15. Litiere S, Alonso A, Molenberghs G: Type I and type II error under random-effects misspecification in generalized linear mixed models. Biometrics 2007; 63:1038–1044Google Scholar

16. Little R, Yau L: Intent-to-treat analysis for longitudinal studies with drop-outs. Biometrics 1996; 52:1324–1333Google Scholar

17. Gallo JJ, Bogner HR, Morales KH, Post EP, Lin JY, Bruce ML: The effect on mortality of a practice-based depression intervention program for older adults in primary care: a cluster randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2007; 146:689–698Google Scholar

18. Katon WJ, Schoenbaum M, Fan MY, Callahan CM, Williams J Jr, Hunkeler E, Harpole L, Zhou XH, Langston C, Unützer J: Cost-effectiveness of improving primary care treatment of late-life depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005; 62:1313–1320Google Scholar

19. Rost K, Nutting P, Smith JL, Elliott CE, Dickinson M: Managing depression as a chronic disease: a randomised trial of ongoing treatment in primary care. BMJ 2002; 325:934Google Scholar

20. Unutzer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, Williams JW Jr, Hunkeler E, Harpole L, Hoffing M, Della Penna RD, Noel PH, Lin EH, Tang L, Oishi S: Depression treatment in a sample of 1,801 depressed older adults in primary care. J Am Geriatr Soc 2003; 51:505–514Google Scholar

21. Hunkeler EM, Katon W, Tang L, Williams JW Jr, Kroenke K, Lin EH, Harpole LH, Arean P, Levine S, Grypma LM, Hargreaves WA, Unützer J: Long term outcomes from the IMPACT randomised trial for depressed elderly patients in primary care. BMJ 2006; 332:259–263Google Scholar

22. Schulberg HC, Lee PW, Bruce ML, Raue PJ, Lefever JJ, Williams JW Jr, Dietrich AJ, Nutting PA: Suicidal ideation and risk levels among primary care patients with uncomplicated depression. Ann Fam Med 2005; 3:523–528Google Scholar

23. Szanto K, Reynolds CF 3rd, Conwell Y, Begley AE, Houck P: High levels of hopelessness persist in geriatric patients with remitted depression and a history of attempted suicide. J Am Geriatr Soc 1998; 46:1401–1406Google Scholar

24. Szanto K, Mulsant BH, Houck P, Dew MA, Reynolds CF 3rd: Occurrence and course of suicidality during short-term treatment of late-life depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003; 60:610–617Google Scholar

25. Lecrubier Y: How do you define remission? Acta Psychiatr Scand 2002; 106:7–11Google Scholar

26. Thase ME, Entsuah AR, Rudolph RL: Remission rates during treatment with venlafaxine or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Br J Psychiatry 2001; 178:234–241Google Scholar

27. Reynolds CF 3rd, Dew MA, Pollock BG, Mulsant BH, Frank E, Miller MD, Houck PR, Mazumdar S, Butters MA, Stack JA, Schlernitzauer MA, Whyte EM, Gildengers A, Karp J, Lenze E, Szanto K, Bensasi S, Kupfer DJ: Maintenance treatment of major depression in old age. N Engl J Med 2006; 354:1130–1138Google Scholar

28. Gilbody S, Whitty P, Grimshaw J, Thomas R: Educational and organizational interventions to improve the management of depression in primary care: a systematic review. JAMA 2003; 289:3145–3151Google Scholar

29. Bruce ML, Leaf PJ, Rozal GP, Florio L, Hoff RA: Psychiatric status and 9-year mortality data in the New Haven Epidemiologic Catchment Area study. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:716–721Google Scholar

30. Berkman LF, Blumenthal J, Burg M, Carney RM, Catellier D, Cowan MJ, Czajkowski SM, DeBusk R, Hosking J, Jaffe A, Kaufmann PG, Mitchell P, Norman J, Powell LH, Raczynski JM, Schneiderman N; Enhancing Recovery in Coronary Heart Disease Patients Investigators (ENRICHD): Effects of treating depression and low perceived social support on clinical events after myocardial infarction: the Enhancing Recovery in Coronary Heart Disease Patients (ENRICHD) Randomized Trial. JAMA 2003; 289:3106–3116Google Scholar