Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor Use and Risk of Gestational Hypertension

Abstract

Objective: The purpose of this study was to assess the effects of treatment with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) on the risks of gestational hypertension and preeclampsia. Method: The authors analyzed data from 5,731 women with nonmalformed infants and no underlying hypertension who participated in the Slone Epidemiology Center Birth Defects Study from 1998 to 2007. Gestational hypertension was defined as incident hypertension diagnosed after 20 weeks of pregnancy, with and without proteinuria (i.e., with and without preeclampsia). The risks of gestational hypertension and preeclampsia were compared between women who did and did not receive SSRI treatment during pregnancy. Relative risks and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated using the Cox proportional hazards model, adjusting for prepregnancy sociodemographic, lifestyle, reproductive, and medical factors. Results: Gestational hypertension was present in 9.0% of the 5,532 women who were not treated with SSRIs and 19.1% of the 199 women who were treated with SSRIs. Among women who received treatment, gestational hypertension was present in 13.1% of the 107 women who received treatment only during the first trimester and in 26.1% of the 92 women who continued treatment beyond the first trimester. The occurrence of preeclampsia was 2.4% among women who were not treated with SSRIs, 3.7% among women who were exposed to SSRIs only during the first trimester, and 15.2% among women who continued SSRI treatment beyond the first trimester. Relative to women who did not receive treatment, the adjusted relative risk of preeclampsia was 1.4 for women who discontinued treatment and 4.9 for women who continued treatment. Conclusion: SSRI exposure during late pregnancy—whether a causal factor or not—might identify women who are at an increased risk for gestational hypertension and preeclampsia. Further investigation is needed in order to separate the effects of treatment with SSRIs from those of underlying mood disorders.

Studies have suggested that 12%–25% of all pregnant women display some signs of depression (1 , 2) and 2%–13% are treated with antidepressants (3 , 4) . The most commonly used antidepressants among pregnant women are selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs [ 3 , 4 ]). Antidepressants can control mood effectively and reduce the risks of serious consequences associated with untreated depression for both the mother and her offspring (5 , 6) . However, the use of antidepressants during pregnancy could be potentially associated with adverse effects on the fetus. Although findings have not been consistent for some outcomes (7 – 12) , first trimester exposure to certain SSRIs has been associated with specific birth defects (13 – 16) , and SSRI use during late pregnancy has been associated with pulmonary hypertension of the newborn (17) , prematurity (18 – 21) , low birth weight (20 , 21) , small weight for gestational age (22) , and various other neonatal complications (18 – 20 , 23) . Very few studies have focused on the potential medical and obstetrical adverse effects of antidepressants on the mothers themselves. A leading cause of morbidity and mortality during pregnancy is preeclampsia, clinically recognized by gestational hypertension and proteinuria (24 , 25) . It has been suggested that psychological conditions, such as stress (26) , anxiety, and depression (27 , 28) , may trigger the pathogenic vascular processes that lead to this condition. Serotonin may play an important role in the etiology of preeclampsia through its vascular and hemostatic effects (29) , and SSRIs have been shown to affect circulating serotonin levels (30) . The few studies that have suggested an elevated risk of preeclampsia among pregnant women with depression did not assess the potential independent effect of medications (27 , 28) . If an association between pregnant women with depression and an increased risk for preeclampsia exists, it would still be unclear whether this association is a result of biological or behavioral factors intrinsic to women with mood disorders, medications used to treat the disorders, or a combination of both. Women who are treated with medications for depression and are pregnant or planning a pregnancy often struggle, along with their doctors, with the decision about treatment options, and a critical clinical question is whether to continue or discontinue antidepressant treatment during pregnancy. To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the risk of gestational hypertension and preeclampsia associated with the continuation and discontinuation of antidepressant use beyond the first trimester.

Method

Study Population

Data from the Slone Epidemiology Center Birth Defects Study, a multicenter case control surveillance program of birth defects in relation to environmental exposures (particularly medications [ 13 , 17 ]), were analyzed. More than 35,000 mothers of babies with and without birth defects from the greater metropolitan areas of Philadelphia, San Diego, and Toronto as well as selected regions in Iowa, Massachusetts, and New York State have been interviewed via the study program since 1976. Participants are identified through review of admissions and discharges at major birth hospitals and pediatric referral hospitals and clinics, logbooks at perinatal intensive care units, weekly telephone contact with collaborators at newborn nurseries at community hospitals, and collaborations with state birth defects registries. Since 1998, the study has also included a random sample of births in Massachusetts. The mothers of nonmalformed infants are recruited independently from any exposure and therefore provide an estimate of the distribution of exposures (including the use of medications) within the study population. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained from each of the participating institutions, and mothers provide informed consent before participation in the study.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

We restricted our analyses to a retrospective cohort of women who gave birth to nonmalformed live-born babies between 1998 and 2007 and were ascertained either at the hospital-based centers or through the Massachusetts birth registry (N=5,912). Women with elective terminations, miscarriages, or stillbirths were not included, since most of these women were not at risk for the outcomes of interest, which occurred after 20 weeks of gestation.

Exposure Ascertainment and Definitions

Within 6 months of delivery, trained nurses who were unaware of the study hypotheses conducted a 45- to 60-minute telephone interview with the participating mothers. The purpose of the interview was to collect data on demographic, reproductive, and medical factors as well as cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption, occupational exposures, and dietary intake. Additionally, the interview included a series of increasingly detailed questions designed to collect data regarding medications (prescription, over-the-counter, vitamins/minerals, and herbal products) taken any time from 2 months prior to conception throughout pregnancy (31) . Interview questions were standardized and included a list of indications and specific conditions (e.g., depression) and specific drugs (e.g., fluoxetine). Whenever possible, reported medications were verified by asking the subject to read information from the medication container. Identification of the timing of drug exposure was facilitated using a 12-month calendar covering periods before and after pregnancy. Significant dates (e.g., last menstrual period, holidays) were marked to help enhance recall. Data on medication were collected for starting and discontinuation dates, duration, frequency, indication, form, and number of pills per day. The interview also elicited information regarding subjects’ last menstrual period, based on either maternal recall or ultrasound exam. The last menstrual period allows for an estimation of the due date, approximate conception date, and gestational age at birth. We identified women who were receiving SSRI treatment 2 months before pregnancy and then categorized them into the following two groups: 1) those women who discontinued their treatment before the end of the first trimester and 2) those women who continued treatment after the first trimester. Since very few women initiated SSRI treatment during pregnancy (N=36), assessing the effect of starting treatment during pregnancy would have been less clinically relevant and statistically underpowered, and these women were not analyzed separately (no cases of preeclampsia were observed among these women). Treatment with non-SSRI antidepressants was classified in a similar manner.

Outcome Ascertainment and Definition

Women were specifically asked whether a healthcare provider had diagnosed them with high blood pressure or preeclampsia/toxemia during their pregnancy, and if so, the dates when the condition started and ended and whether medication was used to treat the condition. Given the potential misclassification of pregnancy-induced hypertension with and without preeclampsia, we combined the two diagnoses in our main analyses. Thus, gestational hypertension was defined as incident hypertension during pregnancy with and without proteinuria (i.e., with and without preeclampsia/toxemia). To exclude underlying hypertension as a potential source of both confounding and outcome misclassification bias, we restricted the definition of gestational hypertension to that first diagnosed after week 20 of pregnancy. Consequently, we excluded 145 women with an early diagnosis of hypertension from all analyses. For each woman with gestational hypertension, the onset date was defined as the gestational day when gestational hypertension was first diagnosed.

Statistical Analysis

We consider our study to be a retrospective cohort design. Using women who did not receive SSRI treatment during pregnancy as the reference group, we estimated the relative risk of gestational hypertension for those women who discontinued SSRI treatment before the end of the first trimester and those women who continued treatment beyond the first trimester. Characteristics of the two latter groups were compared using chi-square analyses and Fisher’s exact tests. Relative risks and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated for each outcome using Cox proportional hazards model, with time measured in days since week 20 of gestation. The following potential confounders were considered: region, birth year, maternal age, race/ethnicity, education, family income, gravidity, number of fetuses, prepregnancy body mass index (kg/m 2 ), age at menarche, diabetes mellitus, infertility treatment, cigarette smoking, coffee and alcohol intake, and use of illicit drugs or other psychotherapeutic medications during pregnancy (24 , 32 – 36) . In the Cox proportional hazards model, we retained those factors associated with the outcome in our study population (even if the association was not statistically significant). The analyses were repeated separately for preeclampsia and gestational hypertension without preeclampsia. Several secondary analyses were also conducted. Because of the different heritability, clinical manifestations, and prognosis of early- and late-onset gestational hypertension, these conditions were distinguished according to the timing of onset (33 , 34 , 37 , 38) . Gestational hypertension was considered early-onset when it began between 20 and 32 weeks after the last menstrual period, and gestational hypertension that began after 32 weeks following the last menstrual period was considered late-onset. We analyzed primigravidae women separately from multigravidae women and women who smoked cigarettes separately from women who did not smoke cigarettes. In addition, our analyses were restricted to singleton births (39) . Effect measure modification on a multiplicative scale was formally tested using the Wald test comparing whether two stratum-specific relative risks were equivalent. We also verified the proportional hazards assumption by including in the models an interaction term for time and treatment with SSRIs.

Results

Of the 5,731 women without pregestational hypertension, 538 (9.4%) reported being diagnosed with gestational hypertension. Among these, 153 (28.4%) developed preeclampsia (2.7% of all subjects). A total of 199 women (3.5%) were being treated with SSRIs 2 months before conception (191 used these medications for mood disorders). Among this group of women, 107 discontinued SSRI treatment before the end of the first trimester, and 92 continued treatment beyond the first trimester ( Figure 1 ). Most women maintained their exposure status during the later trimesters. However, twelve of the women (11.2%) who discontinued treatment restarted their treatment, and six women (6.5%) in the continuing treatment group discontinued treatment later in pregnancy.

a Non-SSRI antidepressants include tricyclic antidepressants and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors.

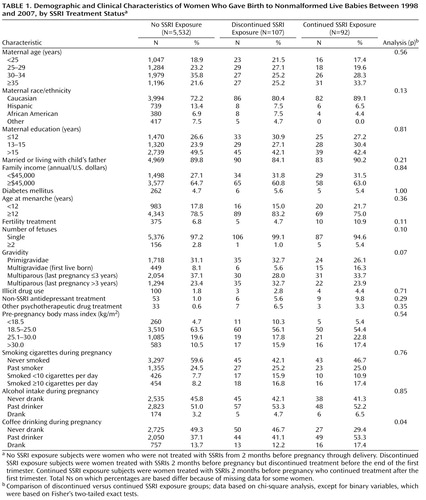

Maternal characteristics based on SSRI treatment status are shown in Table 1 . Women who discontinued and continued treatment did not differ substantially in their baseline characteristics. The risk of gestational hypertension and/or preeclampsia was associated with the following variables: region, younger maternal age, Caucasian ethnic background, unmarried or not living with the child’s father, lower family income, younger age at menarche, cigarette smoking, diabetes mellitus, higher prepregnancy body mass index, multiple gestations (twins or more), primigravidae, and history of fertility treatment. These variables were included in our final models.

Sixty-eight women were being treated with non-SSRI antidepressants 2 months before pregnancy (16 women were treated with serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors [SNRIs]). Among this group of women, 13 (19.1% [three women were treated with SNRIs]) developed gestational hypertension and four (5.9% [one woman was treated with SNRIs]) developed preeclampsia. Compared with women who did not receive these antidepressants, the adjusted relative risk for women who were treated with non-SSRI antidepressants immediately before or during pregnancy was 1.58 (95% CI=0.90–2.80) for gestational hypertension and 1.55 (95% CI=0.55–4.38) for preeclampsia. As a result of these small numbers, non-SSRI antidepressant use was not analyzed further, except as a potential confounder.

Figure 2 shows the cumulative occurrences of gestational hypertension and preeclampsia according to SSRI exposure status. Women who were treated with SSRIs had a higher risk for gestational hypertension compared with women who were not exposed to SSRIs. This risk was greater for women who continued treatment relative to women who discontinued treatment ( Table 2 ). The increased risk for gestational hypertension observed among women who continued treatment appeared to be largely attributable to preeclampsia, although there was also an indication of an elevated risk for gestational hypertension without preeclampsia. The results were similar when women who discontinued treatment before the end of the first trimester and did not restart their treatment were compared with women who continued treatment after the first trimester and did not discontinue their treatment during later trimesters. Relative risks did not vary greatly by gravidity or smoking status. In addition, restricting our analyses to singleton births or evaluating women who were exposed to SSRIs only (and not to non-SSRI antidepressants concomitantly) did not significantly alter the results. We did not have the power to evaluate specific SSRIs. There were 146 and 35 early-onset cases of gestational hypertension and preeclampsia, respectively. Compared with women who did not receive treatment with SSRIs, the relative risks among women who continued and discontinued treatment with SSRIs were similar for early- and late-onset gestational hypertension. However, when we compared women who continued treatment with women who did not receive treatment, the relative risk for early onset preeclampsia among women who continued treatment was 16.4 (95% CI=6.2–43.7 [based on six cases among women who continued treatment]), and the relative risk for late-onset preeclampsia among women who continued treatment was 3.5 (95% CI=1.6–7.5 [based on eight cases among women who continued treatment]). There was no indication of violation of the proportional hazards assumption in any of the analyses.

a No SSRI exposure subjects were women who were not treated with SSRIs from 2 months before pregnancy through delivery. Discontinued SSRI exposure subjects were women treated with SSRIs 2 months before pregnancy but discontinued treatment before the end of the first trimester. Continued SSRI exposure subjects were women treated with SSRIs 2 months before pregnancy who continued treatment after the first trimester.

Discussion

In the present study, we found that periconceptional SSRI treatment among pregnant women was associated with a higher risk for gestational hypertension and, particularly, preeclampsia. Further, the risk for preeclampsia was greater among women who continued SSRI treatment after the first trimester (15.2%) compared with women who did not receive treatment with SSRIs (2.4%) and women who discontinued treatment with SSRIs (3.7%). The following four possible factors might explain these findings: 1) these outcomes are a result of treatment with SSRIs; 2) underlying mood disorders are associated with an increased risk for these outcomes; 3) methodological limitations create a spurious association between SSRIs and these outcomes; or 4) a combination of all three factors.

Causal Effect of SSRIs

Treatment with SSRIs exclusively during early pregnancy, when placentation occurs, was not associated with a higher risk for preeclampsia. Thus, if real, the effect of SSRIs on preeclampsia might not be mediated via placentation but rather through hypertension or vascular effects later during pregnancy. Serotonin may play a role in the pathophysiology of preeclampsia through its effects on hemostasis and vascular tone in uteroplacental tissues (29 , 40 , 41) . In addition, SSRIs inhibit synthesis of nitric oxide, a vasodilator that appears to play a role in vascular tone and reactivity both in utero and during postnatal life (42 – 44) . The more recently introduced SNRIs can cause elevations of diastolic blood pressure, probably as a result of their noradrenergic effects (45) , but we did not have sufficient numbers of exposed women to examine the outcomes associated with these medications.

Confounding by Depression or Other Mood Disorders

The association between SSRIs and preeclampsia might stem from underlying mood disorders (e.g., depression, anxiety), which could reflect both the indication for treatment and the ultimate cause of preeclampsia, or it could represent a marker for a higher risk (e.g., a genetic-linked predisposition for both depression or anxiety and preeclampsia). For example, depression or anxiety could induce vasoconstriction and uterine artery resistance through an altered excretion of vasoactive hormones and other neuroendocrine transmitters (5) . In a Finnish study (27) , anxiety and depression during pregnancy were associated with a threefold increased risk for preeclampsia, and a similar association was found in a recent case-control study (28) . However, these studies did not examine the effects of these conditions independent of treatment. In the present study, the greater occurrences of gestational hypertension and preeclampsia found among women who were treated with non-SSRI antidepressants (e.g., SNRIs, tricyclic antidepressants) relative to women who were not treated with non-SSRIs, albeit nonstatistically significant, suggest that women who need antidepressive agents might be at an increased risk for these outcomes and that the increased risk might not be related to SSRIs themselves. The small number of outcomes among women who received treatment with non-SSRI antidepressants limited our ability to examine the effect of these medications compared with the effect of SSRIs. Unfortunately, among women with depression, we were unable to compare those who received SSRI treatment with those who did not receive treatment, since we did not identify mood disorders among those women who did not report drug treatment. However, although it might appear that such comparisons would have been ideal in order to adjust for confounding by the underlying condition, depression severity and other potential risk factors for preeclampsia among women with depression may differ between individuals who are and are not treated with specific antidepressants. For example, it has been observed that among pregnant women with a diagnosis of depression, those who receive treatment with SSRIs have clinical indicators suggesting that they have a greater severity of depression when compared with women who do not receive SSRI treatment (22) .

Therefore, in addition to comparing women who received antidepressant treatment with women who did not receive antidepressant treatment, we compared those women who discontinued SSRI treatment before the end of the first trimester with those who continued SSRI treatment after the first trimester. Although the latter two groups did not differ significantly in most baseline variables ( Table 1 ), these women might differ in other unmeasured characteristics that could potentially explain our findings. In particular, we did not have a measure of depression severity for women who discontinued or continued SSRI treatment. Those women who continued to receive SSRI treatment might have had better control of their symptoms than those who discontinued their treatment, or they might have had a more severe condition that required pharmacological treatment. Thus, the higher risk for preeclampsia associated with continuation of treatment after the first trimester might simply reflect a more severe mood disorder. In the absence of treatment randomization, comparing these two groups might have reduced, but not eliminated, the possibility of confounding by depression severity.

Confounding by Other Factors

Characteristics such as high prepregnancy body mass index are positively associated with both SSRI treatment and preeclampsia (46) . Failure to adjust for these confounders could overestimate the risks associated with drug treatment. In our analyses, estimates adjusted for these confounders did not differ substantially from the unadjusted estimates. Other important socioeconomic and lifestyle factors, such as family income and maternal education level, were also considered but did not appear to be major confounders in our study population. For an unmeasured confounder to have an appreciable impact, it would have had to be reasonably prevalent and strongly associated with both SSRI use during pregnancy and the risk for gestational hypertension.

Information Bias

A potential limitation to the study lies in the outcome data, which were based on self-report, since we did not have routine access to obstetric notes in the mothers’ medical records. Thus, under- and overreporting of events, misclassification of the exact date of onset, and cross-classification of preeclampsia and transient hypertension during pregnancy were possible. Underdiagnosis is unlikely, since more than 99% of the mothers in our study population had prenatal care, in which screening for gestational hypertension and proteinuria is standard practice. Data errors are likely to have been minimized by the use of a carefully designed questionnaire, with specific questions pertaining to hypertension onset and preeclampsia, as diagnosed by a healthcare provider, administered within 6 months of delivery by trained nurses. Further, the data offer evidence of the general validity of the outcome classification. First, the reported occurrences of gestational hypertension among primiparous women (12.6%) and the overall occurrences of preeclampsia (2.7%) in our study population are similar to those found in population-based studies (47 , 48) . Second, the frequency and effect of other known risk factors (e.g., gravidity, number of fetuses, and maternal weight) are similar to those consistently reported in the literature (24 , 32 – 36) . Other previously suggested risk factors, such as advanced maternal age, were not associated with a higher frequency of gestational hypertension in our study, most likely because we excluded women with pregestational hypertension (i.e., these factors were associated with hypertension diagnosed before 20 weeks of gestation). Our failure to find the previously suggested protective effect of smoking (49) might be a result of various factors, including differences among characteristics of women who smoked over time and methodological factors. In addition, if the reported outcomes were misclassified similarly for women who were and were not treated with SSRIs, the effect would then be to bias our results toward a null effect of SSRIs. Of greater concern would be a differential misclassification of outcome among women who were and were not treated with SSRIs. For example, if women who received treatments, such as antidepressant therapy, were diagnosed with gestational hypertension or preeclampsia more readily, this situation would indeed tend to bias the association between SSRIs and gestational hypertension/preeclampsia toward an increased risk among women who were treated with SSRIs and for women who continued versus discontinued their treatment. However, although more intensive monitoring and diagnosis would likely produce stronger associations for gestational hypertension, which may be variably detected, such monitoring and diagnosis would be less likely to do so for preeclampsia, which is a clinically significant event that is difficult to overlook.

Studies that collect medication prescribing or dispensing data might not capture actual use and time-of-use during pregnancy, leading to potential misclassification of exposure (50) . Our study collected data on medications actually taken by the mother, and timing-of-use was systematically collected. Although data based on maternal recall might be subject to misclassification, we do not feel that recall bias was a major concern in the present study, since SSRIs are regularly used for treatment—and for nontrivial reasons—and the study interviewers specifically probed for the use of antidepressants and were unaware of the study hypothesis. Although underreporting of antidepressant use is possible, since women might be reluctant to disclose such information, it is reassuring that the prevalence of SSRI use in our study population was consistent with that reported by prospective studies (4 , 22) . Further, if women with the study outcomes were less likely to report their treatment with SSRIs, such underreporting would lead to an underestimation of the true risk.

SSRI, Preeclampsia, and Prematurity/Fetal Growth Restriction

Several (18 – 22) , but not all (8 – 12) , studies have suggested that SSRIs may be associated with a greater risk for prematurity and/or fetal growth restriction. Since preeclampsia is a known risk factor for these outcomes (51) , it is possible that the suggested associations between SSRIs and prematurity or fetal growth restriction may be mediated through an elevated risk of preeclampsia among women who are treated with SSRIs.

Conclusion

The benefits of treating depression during pregnancy (52) and the risk of relapse associated with treatment discontinuation (6) are well described. The present study can only inform the risk component of the risk-benefit assessment. Our data suggest that SSRI exposure during pregnancy might identify women who are at an increased risk for gestational hypertension and preeclampsia. Continuation of SSRI treatment beyond the first trimester might be associated with a higher risk when compared with discontinuation of SSRI treatment soon after pregnancy awareness. However, we were unable to disentangle whether the risk is attributable to the drug treatment, to the underlying mood disorder, or a combination of both. In addition, we were limited by potential differential misclassification of the outcomes. Thus, future efforts, including well-designed and powered prospective cohort studies, are needed to confirm or refute the present findings. Independent of a causal link or mechanism, if the present findings are confirmed, women who are exposed to SSRIs during pregnancy should be carefully monitored for the occurrence of gestational hypertension and preeclampsia.

1. Evans J, Heron J, Francomb H, Oke S, Golding J: Cohort study of depressed mood during pregnancy and after childbirth. BMJ 2001; 323:257–260Google Scholar

2. Gotlib IH, Whiffen VE, Mount JH, Milne K, Cordy NI: Prevalence rates and demographic characteristics associated with depression in pregnancy and the postpartum. J Consult Clin Psychol 1989; 57:269–274Google Scholar

3. Cooper WO, Willy ME, Pont SJ, Ray WA: Increasing use of antidepressants in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2007; 196:544e1–e5Google Scholar

4. Andrade SE, Raebel MA, Brown J, Lane K, Livingston J, Boudreau D, Rolnick SJ, Roblin D, Smith DH, Willy ME, Staffa JA, Platt R: Use of antidepressant medications during pregnancy: a multisite study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2008; 198:194e1–e5Google Scholar

5. Bonari L, Pinto N, Ahn E, Einarson A, Steiner M, Koren G: Perinatal risks of untreated depression during pregnancy. Can J Psychiatry 2004; 49:726–735Google Scholar

6. Cohen LS, Altshuler LL, Harlow BL, Nonacs R, Newport DJ, Viguera AC, Suri R, Burt VK, Hendrick V, Reminick AM, Loughead A, Vitonis AF, Stowe ZN: Relapse of major depression during pregnancy in women who maintain or discontinue antidepressant treatment. JAMA 2006; 295:499–507Google Scholar

7. Hallberg P, Sjoblom V: The use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors during pregnancy and breast-feeding: a review and clinical aspects. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2005; 25:59–73Google Scholar

8. Malm H, Klaukka T, Neuvonen PJ: Risks associated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2005; 106:1289–1296Google Scholar

9. Pastuszak A, Schick-Boschetto B, Zuber C, Feldkamp M, Pinelli M, Sihn S, Donnenfeld A, McCormack M, Leen-Mitchell M, Woodland C, Gardner A, Hom M, Koren G: Pregnancy outcome following first-trimester exposure to fluoxetine. JAMA 1993; 269:2246–2248Google Scholar

10. Nulman I, Rovet J, Stewart DE, Wolpin J, Gardner HA, Theis JG, Kulin N, Koren G: Neurodevelopment of children exposed in utero to antidepressant drugs. N Engl J Med 1997; 336:258–262Google Scholar

11. Kulin NA, Pastuszak A, Sage SR, Schick-Boschetto B, Spivey G, Feldkamp M, Ormond K, Matsui D, Stein-Schechman AK, Cook L, Brochu J, Rieder M, Koren G: Pregnancy outcome following maternal use of the new selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: a prospective controlled multicenter study. JAMA 1998; 279:609–610Google Scholar

12. Suri R, Altshuler L, Hendrick V, Rasgon N, Lee E, Mintz J: The impact of depression and fluoxetine treatment on obstetrical outcome. Arch Womens Ment Health 2004; 7:193–200Google Scholar

13. Louik C, Lin AE, Werler MM, Hernandez-Diaz S, Mitchell AA: First-trimester use of selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors and the risk of birth defects. N Engl J Med 2007; 356:2675–2683Google Scholar

14. Alwan S, Reefhuis J, Rasmussen SA, Olney RS, Friedman JM: Use of selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors in pregnancy and the risk of birth defects. N Engl J Med 2007; 356:2684–2692Google Scholar

15. Cole JA, Ephross SA, Cosmatos IS, Walker AM: Paroxetine in the first trimester and the prevalence of congenital malformations. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2007; 16:1075–1085Google Scholar

16. Wogelius P, Norgaard M, Gislum M, Pedersen L, Munk E, Mortensen PB, Lipworth L, Sorensen HT: Maternal use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and risk of congenital malformations. Epidemiology 2006; 17:701–704Google Scholar

17. Chambers CD, Hernández-Díaz S, Van Marter LJ, Werler MM, Louik C, Jones KL, Mitchell AA: Selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors and risk of persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn. N Engl J Med 2006; 354:579–587Google Scholar

18. Chambers CD, Johnson KA, Dick LM, Felix RJ, Jones KL: Birth outcomes in pregnant women taking fluoxetine. N Engl J Med 1996; 335:1010–1015Google Scholar

19. Davis RL, Rubanowice D, McPhillips H, Raebel MA, Andrade SE, Smith D, Yood MU, Platt R: Risks of congenital malformations and perinatal events among infants exposed to antidepressant medications during pregnancy. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2007; 16:1086–1094Google Scholar

20. Kallen B: Neonate characteristics after maternal use of antidepressants in late pregnancy. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2004; 158:312–316Google Scholar

21. Wen SW, Yang Q, Garner P, Fraser W, Olatunbosun O, Nimrod C, Walker M: Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2006; 194:961–966Google Scholar

22. Oberlander TF, Warburton W, Misri S, Aghajanian J, Hertzman C: Neonatal outcomes after prenatal exposure to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressants and maternal depression using population-based linked health data. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006; 63:898–906Google Scholar

23. Costei AM, Kozer E, Ho T, Ito S, Koren G: Perinatal outcome following third trimester exposure to paroxetine. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2002; 156:1129–1132Google Scholar

24. Roberts JM: Endothelial dysfunction in preeclampsia. Semin Reprod Endocrinol 1998; 16:5–15Google Scholar

25. MacKay AP, Berg CJ, Atrash HK: Pregnancy-related mortality from preeclampsia and eclampsia. Obstet Gynecol 2001; 97:533–538Google Scholar

26. Klonoff-Cohen HS, Cross JL, Pieper CF: Job stress and preeclampsia. Epidemiology 1996; 7:245–249Google Scholar

27. Kurki T, Hiilesmaa V, Raitasalo R, Mattila H, Ylikorkala O: Depression and anxiety in early pregnancy and risk for preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol 2000; 95:487–490Google Scholar

28. Qiu C, Sanchez SE, Lam N, Garcia P, Williams MA: Associations of depression and depressive symptoms with preeclampsia: results from a Peruvian case-control study. BMC Womens Health 2007; 7:15Google Scholar

29. Bolte AC, van Geijn HP, Dekker GA: Pathophysiology of preeclampsia and the role of serotonin. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2001; 95:12–21Google Scholar

30. Skop BP, Brown TM: Potential vascular and bleeding complications of treatment with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Psychosomatics 1996; 37:12–16Google Scholar

31. Mitchell AA, Cottler LB, Shapiro S: Effect of questionnaire design on recall of drug exposure in pregnancy. Am J Epidemiol 1986; 123:670–676Google Scholar

32. Walker JJ: Pre-eclampsia. Lancet 2000; 356:1260–1265Google Scholar

33. Myatt L, Miodovnik M: Prediction of preeclampsia. Semin Perinatol 1999; 23:45–57Google Scholar

34. Odegard RA, Vatten LJ, Nilsen ST, Salvesen KA, Austgulen R: Risk factors and clinical manifestations of pre-eclampsia. BJOG 2000; 107:1410–1416Google Scholar

35. Ness RB, Roberts JM: Heterogeneous causes constituting the single syndrome of preeclampsia: a hypothesis and its implications. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1996; 175:1365–1370Google Scholar

36. Mills JL, DerSimonian R, Raymond E, Morrow JD, Roberts LJ 2nd, Clemens JD, Hauth JC, Catalano P, Sibai B, Curet LB, Levine RJ: Prostacyclin and thromboxane changes predating clinical onset of preeclampsia: a multicenter prospective study. JAMA 1999; 282:356–362Google Scholar

37. CLASP (Collaborative Low-Dose Aspirin Study in Pregnancy) Collaborative Group: CLASP: a randomised trial of low-dose aspirin for the prevention and treatment of pre-eclampsia among 9,364 pregnant women. Lancet 1994; 343:619–629Google Scholar

38. Sibai BM, Mercer B, Sarinoglu C: Severe preeclampsia in the second trimester: recurrence risk and long-term prognosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1991; 165(5 pt 1):1408–1412Google Scholar

39. Higgins JR, de Swiet M: Blood-pressure measurement and classification in pregnancy. Lancet 2001; 357:131–135Google Scholar

40. Bjoro K, Stray-Pedersen S: In vitro perfusion studies on human umbilical arteries, I: vasoactive effects of serotonin, PGF2 alpha and PGE2. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 1986; 65:351–355Google Scholar

41. Haugen G, Bjoro K, Stray-Pedersen S: Vasoactive effects of intra- and extravascular serotonin, PGE2 and PGF2 alpha in human umbilical arteries. Gynecol Obstet Invest 1991; 31:208–212Google Scholar

42. Abman SH: New developments in the pathogenesis and treatment of neonatal pulmonary hypertension. Pediatr Pulmonol Suppl 1999; 18:201–204Google Scholar

43. Yaron I, Shirazi I, Judovich R, Levartovsky D, Caspi D, Yaron M: Fluoxetine and amitriptyline inhibit nitric oxide, prostaglandin E2, and hyaluronic acid production in human synovial cells and synovial tissue cultures. Arthritis Rheum 1999; 42:2561–2568Google Scholar

44. Finkel MS, Laghrissi-Thode F, Pollock BG, Rong J: Paroxetine is a novel nitric oxide synthase inhibitor. Psychopharmacol Bull 1996; 32:653–658Google Scholar

45. Thase ME: Effects of venlafaxine on blood pressure: a meta-analysis of original data from 3,744 depressed patients. J Clin Psychiatry 1998; 59:502–508Google Scholar

46. Hernandez-Diaz S, Werler MM, Mitchell AA: Gestational hypertension in pregnancies supported by infertility treatments: role of infertility, treatments, and multiple gestations. Fertil Steril 2007; 88:438–445Google Scholar

47. Wallis AB, Saftlas AF, Hsia J, Atrash HK: Secular trends in the rates of preeclampsia, eclampsia, and gestational hypertension, United States, 1987–2004. Am J Hypertens 2008; 21:521–526Google Scholar

48. Vollset SE, Refsum H, Irgens LM, Emblem BM, Tverdal A, Gjessing HK, Monsen AL, Ueland PM: Plasma total homocysteine, pregnancy complications, and adverse pregnancy outcomes: the Hordaland Homocysteine Study. Am J Clin Nutr 2000; 71:962–968Google Scholar

49. Conde-Agudelo A, Althabe F, Belizan JM, Kafury-Goeta AC: Cigarette smoking during pregnancy and risk of preeclampsia: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1999; 181:1026–1035Google Scholar

50. Toh S, Mitchell AA, Werler MM, Hernandez-Diaz S: Sensitivity and specificity of computerized algorithms to classify gestational periods in the absence of information on date of conception. Am J Epidemiol 2008; 167:633–640Google Scholar

51. Sibai B, Marcel Dekker G, Kupferminc M: Pre-eclampsia. Lancet 2005; 365:785–799Google Scholar

52. Cohen LS, Rosenbaum JF: Psychotropic drug use during pregnancy: weighing the risks. J Clin Psychiatry 1998; 59(suppl 2):18–28Google Scholar