An Adoption Study of Parental Depression as an Environmental Liability for Adolescent Depression and Childhood Disruptive Disorders

Abstract

Objective: The authors used an adoption study design to investigate environmental influences on risk for psychopathology in adolescents with depressed parents. Method: Participants were 568 adopted adolescents ascertained through large adoption agencies, 416 nonadopted adolescents ascertained through birth records, and their parents. Clinical interviews with parents and adolescents were used to determine lifetime DSM-IV-TR diagnoses of major depressive disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and substance use disorders in adolescents and major depression in mothers and fathers. Effects of parental depression (either parent with major depression, maternal major depression, and paternal major depression) on adolescent psychopathology were tested in nonadopted and adopted adolescents separately, and interactive effects of parental depression and adoption status were tested. Results: Either parent having major depression and a mother having major depression were associated with a significantly greater risk for major depression and disruptive behavior disorders in both nonadopted and adopted adolescents. Paternal depression did not have a main effect on any psychiatric disorder in adolescents and, with one exception (ADHD in adopted adolescents), did not predict significantly greater likelihoods of disorders in either nonadopted or adopted adolescents. Conclusions: Maternal depression was an environmental liability for lifetime diagnoses of major depression and disruptive disorders in adolescents. Paternal depression was not associated with an increased risk for psychopathology in adolescents.

Compared with children of nondepressed parents, children of depressed parents have a higher risk for depression (1) as well as for attention problems, behavior management problems, and conduct disorder (2 – 5) . While there has been considerable research on mechanisms of risk in these families, no study has provided a direct test of the extent to which there is an environmental effect of parental major depressive disorder (that is, separate from genetic influences) on psychopathology in children. In this study, we investigated the influence of environmental factors on risk for psychopathology in adopted and nonadopted adolescents of depressed parents.

Most empirically supported models of risk in families of depressed parents include factors that are conceptualized as environmental variables, such as harsh parenting and family conflict (6) . Many of these family “environment” variables, however, are genetically influenced (7 , 8) and share common genetic influences with psychopathology in adolescents (9 , 10) ). For example, family conflict is characteristic of families with depressed parents (11) and is associated with adolescent depression (12 , 13) . Rice and colleagues (14) found that family conflict has a stronger association with depression in youths who have an elevated genetic risk for depression. In other words, these findings suggest that associations between family conflict (an environmental risk variable) and psychopathology in youths are at least partially mediated by genetic influences. This raises questions about the extent to which depressed parents create a rearing environment that increases risk for psychopathology in their children.

Most research on the risk for psychopathology in children of depressed parents includes only biological offspring and thus cannot isolate the influence of environmental factors. Some of these studies clearly support environmental mediation. Kim-Cohen and colleagues (15) showed that maternal depression occurring after but not before their child’s birth had a dose-response relationship with child antisocial behavior, and Weissman and colleagues (16) reported associations between remission in maternal depressive symptoms following pharmacological treatment and improvements in child diagnoses and symptoms. These studies, however, do not provide a direct test of environmental mediation that is unambiguously separate from genetic effects. For example, the possibility that the associations are explained by genetic influences on chronicity of maternal depression cannot be ruled out.

Adoption studies provide a method for studying the environmental effect, disentangled from genetic influences, of having a depressed parent. Parent-child adoption designs typically compare risk conferred by biological parents who were not involved in rearing their children and risk conferred by adoptive, rearing parents. The design of the Sibling Interaction and Behavior Study (SIBS), whose sample we used in this investigation, provides a unique opportunity to compare the effect on adolescents of depression in rearing biological parents and in rearing adoptive parents. One methodological concern in adoption designs is the possibility that adopted individuals are exposed to a more restrictive range of home environments than nonadopted individuals as a result of self-selection by adoptive parents and screening of parents during the adoption process (17) . Using the SIBS sample, McGue and colleagues (18) showed that while there is evidence of range restriction in adoptive families on parental disinhibitory psychopathology and socioeconomic status, adoptive families did not differ significantly from nonadoptive families in parental depression and family functioning, which are key variables in our study. In addition, while we cannot rule out the possibility of selective placement, it seems unlikely that biological risk for psychopathology differs in the adolescents of depressed and nondepressed adoptive parents. Information about the mental health of birth parents was not available.

In this article, we report the first parent-child adoption study to investigate the environmental effect of parental major depression, including both maternal and paternal depression, on risk for DSM-IV-TR psychiatric disorders during adolescence. Adolescence is a developmental period when rates of depression and other disorders are rising (19) , and adolescents are exposed daily to environmental influences associated with parental depression. Studying the effects of maternal and paternal depression separately is important. While a large literature has documented the effect of maternal depression on child psychopathology (6) , until recently the effect of paternal depression had largely been ignored. The emerging research shows inconsistent support for the effect of paternal depression on psychopathology in adolescents. Brennan and colleagues (20) found a paternal depression effect on externalizing disorders but not on major depression in 15-year-olds, but their study included only fathers who had substantial contact with the children, whether they were biological fathers or stepfathers. Klein and colleagues (1) found that paternal depression did not predict depression in adolescents and young adults unless the offspring’s depressive episodes were at least moderate in severity. Lieb and colleagues (4) found a significant effect of paternal depression on offspring depression but not substance use disorder by late adolescence or young adulthood. However, their study had the significant limitation of using offspring reports for depression diagnoses for both offspring and fathers. These contradictory findings suggest that paternal depression is in need of further study.

We hypothesized that, consistent with psychosocial models of the transmission of risk in families with a depressed parent, environmental influences contribute to an increased risk in families with a depressed mother. In light of the inconsistent evidence for an effect of paternal depression, we made no a priori prediction about risk in families with a depressed father. To the extent that parental depression has an effect, we predicted that it would be associated with an elevated risk for psychopathology both in adolescents with depressed biological parents and in adolescents with depressed adoptive parents, thus providing support for an environmental liability of parental depression.

Method

Participants

Participants were study subjects in the Sibling Interaction and Behavior Study, a longitudinal, community-based study of adoptive (N=409) and nonadoptive (N=208) families. Adoptive families were systematically ascertained from infant placements by three large private adoption agencies and are representative of this type of placement in the state of Minnesota. Nonadoptive families were ascertained from state birth records and are representative of the population of Minnesota. All families had two participating adolescent siblings who were no more than 5 years apart in age and between the ages of 11 and 20 years. Adoptive families had either a pair of participating adopted siblings who were not biologically related to each other or to either rearing parent or one participating adopted adolescent who was not related to either rearing parent. In nonadoptive families, participating adolescents were full biological siblings and the biological offspring of one or both rearing parents. Nonbiological rearing parents in the nonadoptive families (i.e., stepparents) were not included in this study. Two adopted adolescents were ruled ineligible after participation. The final sample consisted of 692 adopted and 416 nonadopted adolescents, each with at least one participating parent (586 mothers and 528 fathers).

The adopted and nonadopted adolescents did not differ significantly in mean age (overall mean=14.31 years [SD=1.90]) or percentage female (53.8% female overall), but they did differ significantly in ethnicity. Two-thirds (66.7%) of the adoptive adolescents were Asian, 21.1% were Caucasian, and 12.2% were of other ethnicities; these proportions are representative of the ethnicity of infants adopted in Minnesota during the years that would have made them eligible for SIBS. The ethnicity of the nonadopted sample was representative of the population of Minnesota, with 95.2% Caucasian and the remaining 4.8% having ethnicities other than Asian. Adopted adolescents had been placed in their rearing homes at a mean age of 4.7 months (SD=3.4). A complete description of recruitment and sampling methods can be found elsewhere (18) .

Procedure

Participants were given a description of the study at the research laboratories. All participants provided written informed consent or assent as appropriate. Adolescent lifetime diagnoses of major depressive disorder, conduct disorder, oppositional defiant disorder (regardless of the presence of conduct disorder), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), substance use disorders (abuse of or dependence on alcohol or illicit drugs), and any externalizing disorder (the presence of oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder, ADHD, and/or substance use disorder) were assessed according to DSM-IV-TR criteria. Structured interviews were administered to adolescents and parents in separate rooms by different trained interviewers. The Structured Interview for DSM-III-R (21) was used to assess depression in parents and in adolescents age 16 and older, including assessment of the number of months since their most recent depressive symptoms. The Diagnostic Interview for Children and Adolescents (22 , 23) was used to assess all disorders in adolescents age 15 and younger and all disorders except major depressive disorder in those 16 or older. Additional probes were used to ensure complete coverage of DSM-IV-TR symptomatology.

Symptoms endorsed by either the parent or the adolescent were combined to create diagnoses in adolescents. Diagnoses based on reports by multiple informants have been shown to have greater construct validity (24 , 25) . We demonstrated this in our sample by predicting criterion variables (negative affectivity for major depression and teacher ratings of behavior problems for externalizing disorders) from diagnoses based on mothers’ reports and diagnoses based on adolescents’ reports. Regardless of which reporter was entered first, the second reporter added significantly to the prediction of the criterion variables (see Table S1 in the data supplement that accompanies the online edition of this article). Another concern about using reports from mothers is the potential for negatively biased reports of child psychopathology by currently depressed mothers, which could inflate associations between maternal depression and child psychopathology. We used lifetime diagnoses of major depression, and thus many women were not currently depressed. In addition, we found that diagnoses based on maternal reports significantly predicted the criterion variables in both mothers with and those without major depression, and the effects were not significantly different in these groups (see Table S2 in the online data supplement).

Disorders were considered present if full criteria or full criteria with the exception of one symptom were present. This method was introduced as part of the Research Diagnostic Criteria (26) and has been used in other studies (27) when participants have not completed the period of risk for disorders or when psychopathology is episodic and requires currently asymptomatic reporters to recall symptoms from previous episodes. Diagnoses have good interrater reliability, with Cohen’s kappa values ranging from 0.73 to 0.86.

No data were missing for adolescent disorders. Data on maternal depression were available for 99.0% of the families, and on paternal depression, for 88.9% of the families. For the variable “either parent with major depressive disorder,” cases with missing data for either the mother or the father were included if the parent with available data had a diagnosis of major depression, resulting in data for 91.1% of the families. Families with and without maternal depression data, with and without paternal depression data, and with and without data for “either parent with major depressive disorder” did not differ significantly in mothers’ or fathers’ mean age, educational level, or occupational status, in adolescents’ age or gender, or in rates of any of the adolescent psychiatric disorders. Parents were significantly more likely to be divorced in the small number of families for which parental depression data were missing. Parents were divorced in all (N=6) cases with missing maternal depression data, compared with 9.1% of the cases with complete maternal depression data. Parents were divorced in 48.4% (N=29) of the cases with missing paternal depression data, compared with 4.8% of cases with complete paternal depression data.

Statistical Analyses

A series of binary logistic regressions were used to test the effects of parental depression (i.e., either parent with major depression, maternal major depression, and paternal major depression) in the adopted and nonadopted groups separately and to test the interactions between parental depression and adolescent adoption status. Age and gender were used as covariates in all analyses, and the opposite parent’s depression status was included in analyses with maternal depression and paternal depression. The correlated nature of the sibling data was accounted for using generalized estimating equations (GEE; 28 ) in PROC GENMOD and PROC MIXED, procedures in the SAS software package (SAS Institute, Cary, N.C.). The GEE method clusters data within families, adjusting standard errors for nonindependence.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

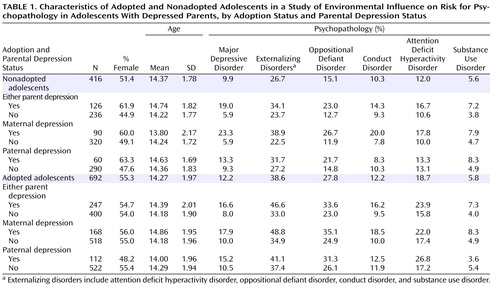

Table 1 presents the sample characteristics and rates of psychopathology by parental depression status and adoption status. Adopted adolescents had higher rates of oppositional defiant disorder (odds ratio=2.44, p<0.001) and ADHD (odds ratio=1.77, p<0.01). These findings are consistent with results from a meta-analysis showing a small but significant elevation in behavior problems in adoptees of all ages compared with nonadopted individuals (29) . More information on differences in rates of DSM-IV-TR disorders between adopted and nonadopted adolescents in the SIBS sample can be found elsewhere (30) . Our rates of DSM-IV-TR disorders in the nonadopted sample are also comparable to rates published in other epidemiological studies (31 , 32) .

Rates of parental major depression (maternal, paternal, or either parent) did not differ significantly by adolescent ethnicity or gender. Notably, they also did not differ significantly for adoptive and nonadoptive parents (either parent was depressed in 34% and 38% of nonadoptive and adoptive families, respectively), demonstrating that screening of parents during the adoption process did not result in lower rates of major depression in adoptive parents compared with nonadoptive parents. Given that the ethnicity of the adolescents varied by adoption status, we tested the interaction between adolescent ethnicity and parental depression (maternal, paternal, and either parent, separately) predicting adolescent psychopathology and found that none of the parental depression variables predicted adolescent psychopathology differently by adolescent ethnicity.

Effects of Parental Depression on Adolescent Psychopathology

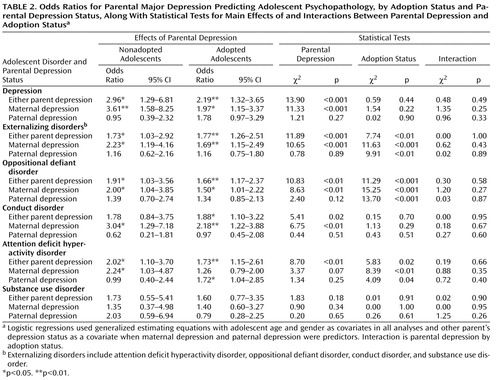

Table 2 presents odds ratios for parental major depression (maternal, paternal, and either parent) predicting the likelihood of psychopathology in adolescents by adoption status, along with statistical tests for main effects and interactions of parental depression and adoption status. Either parent with major depression and maternal major depression were associated with greater likelihoods of most disorders in both adopted and nonadopted adolescents. A notable exception was that the parental depression variables did not significantly predict the likelihood of substance use disorders, which may reflect the expected low rates of substance use disorders in this sample of youths who have not passed the period of risk for substance use disorder. With one exception (ADHD in adopted adolescents), paternal depression was not associated with risk for psychopathology as a main effect or within the nonadopted and adopted adolescents.

The significant odds ratios for adoptive parents’ major depression, specifically adoptive mothers’ major depression, predicting adolescent psychopathology are supportive of environmental influences contributing to risk in families with depressed mothers. In addition, none of the interactions between parental major depression, maternal major depression, or paternal major depression and adoption status were significant, indicating that the associations between parental depression and adolescent psychopathology did not differ significantly for nonadopted and adopted adolescents. Although the odds ratios did not differ significantly by adoption status, the effects were consistently larger in the nonadopted sample. For instance, for every child outcome where the effect of maternal depression was significant, the odds ratio was at least 32% larger in the nonadoption families. This trend is consistent with the expectation that genetic influences, in addition to environmental mediation, account for some of the mother-child association in nonadoption families.

Of the children of depressed parents, 87.4% were exposed to symptoms of their mothers’ major depression during their lifetimes, and 88.2% were exposed to symptoms of their fathers’ major depression during their lifetimes. We tested the extent to which the findings were similar if we included as depressed only parents who had lifetime major depression diagnoses and reported experiencing depressive symptoms during their child’s lifetime. We found that for both the adopted and nonadopted adolescents, the odds ratios that were significant using either parent’s lifetime depression remained significant when we included only parents who reported experiencing symptoms during their child’s lifetime, with one exception: the odds ratio for adolescent oppositional defiant disorder in nonadopted adolescents dropped slightly and became nonsignificant (odds ratio=1.78, 95% confidence interval=0.96–3.28, p=0.07).

Discussion

We found that risk for psychopathology during adolescence was elevated in families with depressed mothers, though not in families with depressed fathers. Factors within the families with a depressed mother, including characteristics of the family environment and genes passed from depressed mothers to offspring, likely contribute to risk. However, the environmental nature of these mechanisms is called into question by research showing that genetic factors influence characteristics of the family environment (7 , 8) as well as associations between family environment and adolescent psychopathology (14) . Since typical parent-child studies include biologically related parents and offspring, they are not able to separate the effect of the environment from genetic effects. Our unique parent-child adoption study allowed us to isolate environmental mechanisms of risk and show that the association between maternal depression and risk for adolescent psychopathology is present in families in which the parent and child have a nonbiological relationship (i.e., do not share genes). In other words, risk conferred by depressed mothers has a significant environmental component. This finding supports psychosocial models for the transmission of risk in families with depressed mothers and is consistent with findings from an adoption study that showed modest environmental influences of maternal neuroticism, as a proxy for maternal depression, on maternal ratings of preadolescents’ internalizing symptoms (33) .

As discussed by Rutter et al. (34) and others, there are many ways in which the effects of genes and the environment are not separate, such as epigenetic mechanisms, gene-environment correlations, and interactions between genes and environment. Our findings do not contradict the role of genetic factors or suggest that gene-environment interplay is unimportant. The isolation of the environmental effect from the genetic effect in our study design provided the opportunity to show that there is an environmental liability of maternal depression that cannot be accounted for by genetic factors but that may (and almost certainly does) interact with genetic factors to create risk in children.

The lack of a significant effect of paternal depression on adolescent psychopathology is not surprising in light of the contradictory findings in the literature. The nature of the effect of fathers’ depression appears to be complicated. For example, studies have shown that paternal depression predicts child depression with onsets by early adolescence (20) and depression of at least moderate severity (1) , which may indicate a strong genetic component in the transmission of risk from depressed fathers to offspring. Further research on the effect of paternal depression that uses genetically informative designs and diverse measures of offspring psychopathology at different developmental stages may help clarify the nature of risk in families with depressed fathers.

This study had several strengths, including a large sample of adopted and nonadopted adolescents, participation of mothers and fathers, a design that enabled evaluation of environmental mediation, and diagnostic assessments of DSM-IV-TR disorders with parents and adolescents.

Several limitations of this study should also be addressed. First, while it is particularly important to study environmental effects of parental depression during adolescence when children live with their parents, the power to detect genetic effects of parental depression may be limited in research on adolescents. Adolescents have experienced only a portion of the risk period for the onset of many of the studied disorders, especially substance use disorders, and we can expect many incident cases of mental health problems in this cohort as it ages into adulthood. Previous research on twins suggests that genetic influences increase while the importance of the family environment diminishes during the transition from adolescence to early adulthood (35) . Consequently, it will be especially important to follow the SIBS participants into early adulthood not only to characterize the emergence of genetic effects but also to determine whether parental depression has an enduring environmentally mediated effect on adult children’s mental health.

Second, the samples of adopted and nonadopted adolescents are representative of the populations from which they are drawn. The nonadopted adolescents are primarily Caucasian, which reflects the population of Minnesota but not the ethnic diversity of the United States. The adopted adolescents are largely Asian, which is representative of adoptions through large adoption agencies in Minnesota at the time of recruitment but, again, does not reflect the ethnic composition of the United States. In addition, findings obtained from samples of adopted adolescents may not generalize to other populations because of the effect of adoption on mental health outcomes (30 , 36) . Third, research on evocative effects of youth psychopathology on parental psychopathology (37) suggests that the relationship between depression in parents and psychopathology in children is to some extent reciprocal. While it is unlikely that child psychopathology evokes diagnosable depression in parents (which had average initial onset around the time the child was born for mothers and a year before the child was born for fathers), characteristics of the children may have contributed to subsequent depressive episodes in parents.

In summary, environmental factors contribute to the transmission of risk in families with depressed mothers. Given that psychopathology during childhood and adolescence predicts continued and future psychopathology (38) , understanding the mechanisms underlying risk during adolescence has important implications for prevention and treatment. Our evidence of an environmental liability suggests that risk to children may be reduced with successful treatment of mothers’ depression and associated maladaptive family environment factors (e.g., family stress and parent-adolescent conflict). This is consistent with findings that remission in mothers’ depressive symptoms following pharmacological treatment is associated with improvement in child psychopathology (16) and with preventive interventions that address environmental mechanisms in families with depressed parents (39) . Our findings also suggest the importance of including not only offspring with high genetic risk but also nonbiological children of depressed mothers (adopted children and stepchildren) in these preventive interventions.

1. Klein DN, Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, Seeley JR, Olino TM: Psychopathology in the adolescent and young adult offspring of a community sample of mothers and fathers with major depression. Psychol Med 2005; 35:353–365Google Scholar

2. Beardslee WR, Versage EM, Gladstone TR: Children of affectively ill parents: a review of the past 10 years. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1998; 37:1134–1141Google Scholar

3. Weissman MM, Wickramaratne P, Nomura Y, Warner V, Pilowsky D, Verdeli H: Offspring of depressed parents: 20 years later. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163:1001–1008Google Scholar

4. Lieb R, Isensee B, Hofler M, Pfister H, Wittchen HU: Parental major depression and the risk of depression and other mental disorders in offspring: a prospective-longitudinal community study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2002; 59:365–374Google Scholar

5. Fergusson DM, Lynskey MT: The effects of maternal depression on child conduct disorder and attention deficit behaviours. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1993; 28:116–123Google Scholar

6. Goodman SH, Gotlib IH: Risk for psychopathology in the children of depressed mothers: a developmental model for understanding mechanisms of transmission. Psychol Rev 1999; 106:458–490Google Scholar

7. McGue M, Elkins I, Walden B, Iacono WG: Perceptions of the parent-adolescent relationship: a longitudinal investigation. Dev Psychol 2005; 41:971–984Google Scholar

8. Plomin R, Bergeman CS: The nature of nurture: genetic influence on “environmental” measures. Behav Brain Sci 1991; 14:373–427Google Scholar

9. Burt S, Krueger RF, McGue M, Iacono W: Parent-child conflict and the comorbidity among childhood externalizing disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003; 60:505–513Google Scholar

10. Neiderhiser JM, Reiss D, Hetherington EM: The Nonshared Environment in Adolescent Development (NEAD) project: a longitudinal family study of twins and siblings from adolescence to young adulthood. Twin Res Hum Genet 2007; 10:74–83Google Scholar

11. Fendrich M, Warner V, Weissman MM: Family risk factors, parental depression, and psychopathology in offspring. Dev Psychol 1990; 26:40–50Google Scholar

12. Hammen C, Brennan PA, Shih JH: Family discord and stress predictors of depression and other disorders in adolescent children of depressed and nondepressed women. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2004; 43:994–1002Google Scholar

13. Sheeber L, Hops H, Alpert A, Davis B, Andrews J: Family support and conflict: prospective relations to adolescent depression. J Abnorm Child Psychol 1997; 25:333–344Google Scholar

14. Rice F, Harold GT, Shelton KH, Thapar A: Family conflict interacts with genetic liability in predicting childhood and adolescent depression. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2006; 45:841–848Google Scholar

15. Kim-Cohen J, Moffitt TE, Taylor A, Pawlby SJ, Caspi A: Maternal depression and children’s antisocial behavior: nature and nurture effects. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005; 62:173–181Google Scholar

16. Weissman MM, Pilowsky DJ, Wickramaratne PJ, Talati A, Wisniewski SR, Fava M, Hughes CW, Garber J, Malloy E, King CA, Cerda G, Sood A, Alpert JE, Trivedi MH, Rush A: Remissions in maternal depression and child psychopathology: a STAR*D-Child report. JAMA 2006; 295:1389–1398Google Scholar

17. Stoolmiller M: Implications of restricted range of family environments for estimates of heritability and nonshared environment in behavior-genetic adoption studies. Psychol Bull 1999; 125:392–409Google Scholar

18. McGue M, Keyes M, Sharma A, Elkins I, Legrand L, Johnson W, Iacono WG: The environments of adopted and non-adopted youth: evidence on range restriction from the Sibling Interaction and Behavior Study (SIBS). Behav Genet 2007; 37:449–462Google Scholar

19. Lewinsohn PM, Hops H, Roberts RE, Seeley JR, Andrews JA: Adolescent psychopathology, I: prevalence and incidence of depression and other DSM-III-R disorders in high school students. J Abnorm Psychol 1993; 102:133–144Google Scholar

20. Brennan PA, Hammen C, Katz AR, Le Brocque RM: Maternal depression, paternal psychopathology, and adolescent diagnostic outcomes. J Consult Clin Psychol 2002; 70:1075–1085Google Scholar

21. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID). New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1987Google Scholar

22. Reich W: Diagnostic Interview for Children and Adolescents (DICA). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2000; 39:59–66Google Scholar

23. Welner Z, Reich W, Herjanic B, Jung KG, Amado H: Reliability, validity, and parent-child agreement studies of the Diagnostic Interview for Children and Adolescents (DICA). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1987; 26:649–653Google Scholar

24. Burt SA, Krueger RF, McGue MI, William G: Sources of covariation among attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, and conduct disorder: the importance of shared environment. J Abnorm Psychol 2001; 110:516–525Google Scholar

25. Achenbach TM, McConaughy SH, Howell CT: Child/adolescent behavioral and emotional problems: implications of cross-informant correlations for situational specificity. Psychol Bull 1987; 101:213–232Google Scholar

26. Spitzer RL, Endicott J, Robins E: Research diagnostic criteria: rationale and reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1978; 35:773–782Google Scholar

27. Iacono WG, Carlson SR, Taylor JT, Elkins IJ, McGue M: Behavioral disinhibition and the development of substance use disorders: findings from the Minnesota Twin Family Study. Dev Psychopathol 1999; 11:869–900Google Scholar

28. Liang KY, Zeger SL: Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika 1986; 79:13–22Google Scholar

29. Juffer F, van Ijzendoorn MH: Behavior problems and mental health referrals of international adoptees: a meta-analysis. JAMA 2005; 293:2501–2515Google Scholar

30. Keyes M, Sharma A, Elkins I, Iacono WG, McGue M: The mental health of US adolescents adopted in infancy. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med (in press)Google Scholar

31. Costello EJ, Foley DL, Angold A: 10-year research update review: the epidemiology of child and adolescent psychiatric disorders, II: developmental epidemiology. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2006; 45:8–25Google Scholar

32. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Walters EE: Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005; 62:593–602Google Scholar

33. Eley TC, Deater-Deckard K, Fombone E, Fulker DW, Plomin R: An adoption study of depressive symptoms in middle childhood. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1998; 39:337–345Google Scholar

34. Rutter M, Moffitt TE, Caspi A: Gene-environment interplay and psychopathology: multiple varieties but real effects. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2006; 47:226–261Google Scholar

35. Rice F, Harold GT, Thaper A: Assessing the effects of age, sex, and shared environment on the genetic aetiology of depression in childhood and adolescence. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2002; 43:1039–1051Google Scholar

36. Nickman SL, Rosenfeld AA, Fine P, Macintyre JC, Pilowsky DJ, Howe R-A, Derdeyn A, Gonzales MB, Forsythe L, Sveda SA: Children in adoptive families: overview and update. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2005; 44:987–995Google Scholar

37. Finley GE, Aguiar LJ: The effects of children on parents: adoptee genetic dispositions and adoptive parent psychopathology. J Genet Psychol 2002; 163:503–506Google Scholar

38. Harrington R, Fudge H, Rutter M, Pickles A, Hill J: Adult outcomes of childhood and adolescent depression, I: psychiatric status. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1990; 47:465–473Google Scholar

39. Clarke GN, Hornbrook M, Lynch F, Polen M, Gale J, Beardslee W, O’Connor E, Seeley J: A randomized trial of a group cognitive intervention for preventing depression in adolescent offspring of depressed parents. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001; 58:1127–1134Google Scholar