Two-Year Prevalence and Stability of Individual DSM-IV Criteria for Schizotypal, Borderline, Avoidant, and Obsessive-Compulsive Personality Disorders: Toward a Hybrid Model of Axis II Disorders

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study tracked the individual criteria of four DSM-IV personality disorders—borderline, schizotypal, avoidant, and obsessive-compulsive personality disorders—and how they change over 2 years. METHOD: This clinical sample of patients with personality disorders was derived from the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study and included all participants with borderline, schizotypal, avoidant, or obsessive-compulsive personality disorder for whom complete 24-month blind follow-up assessments were obtained (N=474). The authors identified and rank-ordered criteria for each of the four personality disorders by their variation in prevalence and changeability (remission) over time. RESULTS: The most prevalent and least changeable criteria over 2 years were paranoid ideation and unusual experiences for schizotypal personality disorder, affective instability and anger for borderline personality disorder, feeling inadequate and feeling socially inept for avoidant personality disorder, and rigidity and problems delegating for obsessive-compulsive personality disorder. The least prevalent and most changeable criteria were odd behavior and constricted affect for schizotypal personality disorder, self-injury and behaviors defending against abandonment for borderline personality disorder, avoiding jobs that are interpersonal and avoiding potentially embarrassing situations for avoidant personality disorder, and miserly behaviors and strict moral behaviors for obsessive-compulsive personality disorder. CONCLUSIONS: These patterns highlight that within personality disorders the relatively fixed criteria are more trait-like and attitudinal, whereas the relatively intermittent criteria are more behavioral and reactive. These patterns suggest that personality disorders are hybrids of traits and symptomatic behaviors and that the interaction of these elements over time helps determine diagnostic stability. These patterns may also inform criterion selection for DSM-V.

This article examines the individual criteria of four DSM-IV personality disorders: schizotypal, borderline, avoidant, and obsessive-compulsive. For each disorder we track how each criterion varies over a 2-year period, compared with every other criterion. We do this to rank-order them in terms of their prevalence and changeability or variance within their personality disorder categories, thus providing clues as to the presence and character of underlying dimensions or phenotypes as well as providing data about the centrality and importance of each criterion for future iterations of personality disorder nosology.

The individual criteria for the DSM-IV axis II personality disorders were first articulated in DSM-III. The criteria for borderline personality disorder largely emerged from a burgeoning clinical literature on the disorder (1–5) and from a discriminant function analysis of data from patients judged by clinicians to have borderline personality disorder, compared with samples of patients with other disorders, including schizophrenia and dysthymia (6). The criteria for schizotypal personality disorder were based on descriptions of first-degree relatives of probands with schizophrenia in Danish adoption studies (7). The criteria for most of the personality disorders, however, were proposed by clinicians on the DSM-III Task Force (8).

The selection process of criteria for the DSM-IV personality disorders was built on a database of comorbidity and criterion diagnostic efficiency studies generated by using DSM-III and DSM-III-R personality disorder categories of criteria. Data were available on the sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive power, and phi coefficients of every personality disorder criterion for its own personality disorder category and for other personality disorder categories (summarized in Widiger [9]). Many of the DSM-III and DSM-III-R personality disorder criteria were retained with some revisions but were rank-ordered for DSM-IV on the basis of their importance as measured by their diagnostic efficiency credentials and expert clinician consensus (10).

The DSM-IV personality disorder criteria have often been described as heterogeneous entities. For example, Parker et al. (11) considered personality disorders to be an amalgam of two constructs, personality style and/or disorder. Rating personality styles and manifestations of disorder in a clinical sample of depressed patients, they found that the personality disorder criteria judged to most closely describe personality style often acted as “proxy criteria for assessing disorder because they are, in and of themselves, descriptors of pathological functions.” The only exception was obsessive-compulsive personality disorder, where the criteria seemed independent of disordered functioning. In a review of the treatment of personality disorders, Sanislow and McGlashan (12) noted that clinicians regard some personality disorder criteria as symptoms or symptomatic behaviors and as such as legitimate targets of treatment (e.g., stress-related paranoia, suicidal behavior). In contrast, other criteria are reflections of personality traits or style and are considered irrelevant (or resistant) to intervention (e.g., perfectionism, irritability, proclivity to shame). Similarly, Zanarini et al. (13) considered the criteria for borderline personality disorder to be a mélange of acute symptoms, temperamental traits, or amalgams of both.

Although personality disorder criteria are considered heterogeneous and are often criticized because of this feature, taxonomic investigations of schizotypal personality disorder, borderline personality disorder, avoidant personality disorder, and obsessive-compulsive personality disorder highlight the homogeneity of within-category criteria sets. Previous studies have investigated the internal consistency of personality disorder criteria cross-sectionally and over time and the stability of the criteria longitudinally.

In an earlier study from our research group, Grilo et al. (14) evaluated cross-sectionally the performance characteristics of the DSM-IV personality disorder criteria for schizotypal personality disorder, borderline personality disorder, avoidant personality disorder, and obsessive- compulsive personality disorder in a clinical sample of 668 adults recruited for the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study (15, 16). The personality disorder criteria sets for all four personality disorders demonstrated convergent validity. The criteria for the individual personality disorders correlated better with each other than with criteria for other personality disorders, i.e., the criteria for all four personality disorders were internally consistent to comparable degrees. Two smaller studies with homogeneous patient study groups (17, 18) also reported findings generally consistent with the baseline Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study (14). In a small nonclinical sample evaluated for all DSM-IV personality disorders, however, internal consistency of the criteria sets varied considerably by disorder (19). For the four personality disorders in question, internal consistency of criterion sets was highest for avoidant personality disorder, intermediate for borderline personality disorder and schizotypal personality disorder, and lowest for obsessive-compulsive personality disorder, suggesting more heterogeneity of expression of criteria for the latter in non-treatment-seeking samples.

The temporal coherence of criterion change over 2 years for the four personality disorders investigated in the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study was also evaluated (20). The observed change in each criterion over 2 years was correlated with the observed change in every other criterion over 2 years to determine if there was within-syndrome consistency in the changes. The observed criterion change correlates were consistent within each syndrome (median alpha=0.72 across the four personality disorders) and reasonably specific to that syndrome relative to other disorders. The results supported the validity of these personality disorder criterion sets as representing coherent syndromes.

Two studies of the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study sample have provided information about the longitudinal stability of these criteria. Shea et al. (21) and Grilo et al. (22) reported on the 1-year and 2-year stability, respectively, of schizotypal personality disorder, borderline personality disorder, avoidant personality disorder, and obsessive-compulsive personality disorder as diagnostic categories. Focusing on the 2-year follow-up, significant improvement in the form of diagnostic remission occurred, at rates ranging from 25% in the schizotypal personality disorder sample to 41% in the obsessive-compulsive personality disorder sample. In conjunction with these diagnostic changes, the mean proportion of the criteria met for each of the four personality disorder groups decreased significantly, although a continuous measure of the proportion of the criteria met was significantly correlated. That is, while the number of criteria of each personality disorder decreased over time, the rank-order frequency of the criteria within each personality disorder remained stable. This finding strongly suggests that the criteria constituting specific personality disorders demonstrate a structure as a group that has longitudinal stability.

The generic diagnostic criterion for a personality disorder in DSM-IV is an enduring pattern of inner experience and behavior that is pervasive, inflexible, and of long duration. The study reported here examined the criteria of each of these personality disorders over 2 years to characterize and rank-order them on a hierarchy of prevalence or presence (most to least) and of remission or changeability (least to most). The aim of this study was to identify the criteria that are the most and least enduring for each personality disorder.

Method

Subjects

Study participants were evaluated as part of the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study, a prospective project to examine the longitudinal course of borderline, schizotypal, avoidant, and obsessive-compulsive personality disorders (15). An axis I comparison group meeting the criteria for major depressive disorder but with no personality disorder was also included in the study for contrast. Participants ages 18–45 years were recruited primarily among patients seeking treatment at clinical services affiliated with each of the four recruitment sites in the study; patients with active psychosis, acute substance intoxication or withdrawal, a history of schizophrenia spectrum psychosis, or organicity were excluded. At baseline, the study group comprised 668 participants, 571 of whom met the Diagnostic Interview for Personality Disorders (23) criteria for at least one of the four study personality disorders and 97 of whom displayed major depressive disorder with no personality disorder (for complete demographic, diagnostic, and comorbidity information, see McGlashan et al. [16]). The current report is based on data for 474 personality disorder patients (83% of the initial study group) for whom complete data through 24 months of follow-up were obtained. No significant baseline differences in diagnostic assignments were observed between retained subjects and those not assessed at the 24-month evaluation (χ2=5.77, df=1, n.s.).

Procedures

Potential participants were screened by using a self-report questionnaire consisting of items pertaining to the four targeted personality disorders. Eligible participants from whom we obtained informed consent were interviewed in person by experienced and trained interviewers who were monitored and who received regular ongoing supervision. Individual DSM-IV criteria were assessed with the Diagnostic Interview for Personality Disorders (23), a semistructured interview with assessment criteria on a 3-point scale (0=not present, 1=present but of uncertain clinical significance, 2=present and clinically significant). Interrater reliability (based on 84 pairs of raters) kappa coefficients for the four study personality disorders ranged from 0.68 (borderline personality disorder) to 0.73 (avoidant personality disorder); test-retest kappas (based on 52 cases) ranged from 0.63 (schizotypal personality disorder) to 0.74 (obsessive-compulsive personality disorder); median reliability correlations for criteria scores ranged from 0.79 to 0.91 (interrater) and 0.65 to 0.84 (test-retest) (24). Participants were reinterviewed with the Diagnostic Interview for Personality Disorders at 24 months by an interviewer who was blind to all results from the baseline and repeated assessments. The data are presented descriptively.

Results

Criterion Prevalence and Remission

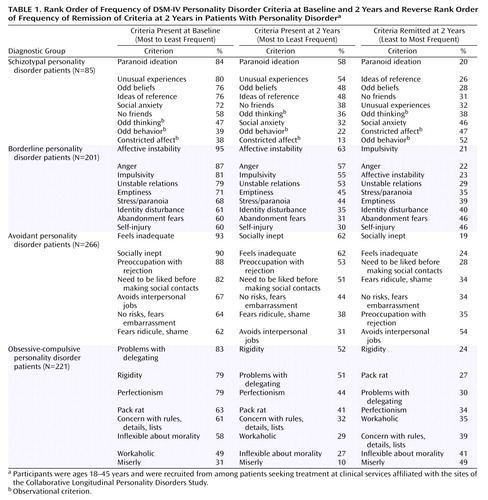

Table 1 details the frequency (percent) of personality disorder criteria with a score of 2 (present and significant) at baseline (column 1) and at 2-year blind follow-up (column 2). Column 3 details the frequency (percent) with which criteria present at baseline (scoring 2) were remitted at 2 years, i.e., had a score of 0 (not present). The values in column 3 do not represent the difference between the values in columns 1 and 2 because column 2 includes criteria that have become newly present and significant between baseline and 2 years. The frequencies are listed by personality disorder diagnostic category, i.e., for patients who met the Diagnostic Interview for Personality Disorders criteria for schizotypal personality disorder (N=85), borderline personality disorder (N=201), avoidant personality disorder (N=266), and obsessive-compulsive personality disorder (N=221). The sum is greater than 474 because many patients had more than one personality disorder.

Table 1 also presents criteria ranked by their presence in each disorder at baseline and 2-year follow-up (most to least) and criteria present at baseline ranked by their rate of remission by 2 years (least to most). The rank ordering highlights the criteria that are both the most prevalent and least changeable over time in each disorder.

Criterion Findings by Disorder

For schizotypal personality disorder, the first six criteria in Table 1 ranked high in frequency at baseline (mean=74%), in contrast to the three observational criteria, which ranked lower (mean=40%). The latter were present considerably less frequently at 2 years (mean=24%), and many that were present at baseline had remitted (mean=46%). In contrast, the (reported) schizotypal personality disorder criteria of paranoid ideation, ideas of reference, odd beliefs, and unusual experiences were among the most prevalent and least changeable criteria.

For borderline personality disorder, all criteria were highly prevalent at baseline. Affective instability, anger, and impulsivity were the most frequent, and identity disturbance, abandonment fears, and self-injury were the least frequent, although still with a frequency of at least 60%. By 2 years the prevalence of the criteria decreased approximately 25%–30%, but the rank ordering of prevalence was exactly the same as at baseline. The rank ordering of criteria that remitted (least to most) was almost the same. For borderline personality disorder, impulsivity, anger, and affective instability were the most frequent and stable criteria, and identity disturbance, abandonment fears, and self-injurious behavior were the least frequent and most changeable.

For avoidant personality disorder all criteria were well represented at baseline (all with frequencies of more than 60%), and they tended to keep the same rank order over time vis à vis prevalence and resistance to remission. Feelings of inadequacy, social ineptness, and a need to be certain of being liked before making social contacts were the most prevalent and stable, and worries about shame and risks of exposure (especially at jobs) were the least prevalent and stable.

For obsessive-compulsive personality disorder the criteria were more variably represented at baseline (31%–83% frequency), but they too tended to retain their rank order of prevalence over time. Rigidity, problems delegating, and perfectionism were the most prevalent and stable criteria. Miserliness was the least represented and most variable.

Discussion

The criteria for schizotypal personality disorder, borderline personality disorder, avoidant personality disorder, and obsessive-compulsive personality disorder, despite limitations in available empirical evidence for their development, have undergone only minor revisions since their introduction in DSM-III. Despite the phenomenological heterogeneity of the DSM-IV personality disorder criteria sets—with criteria representing a variety of traits and symptomatic behaviors and reflecting sometimes normal and sometimes pathological dimensions of personality in clinical samples—these sets demonstrate high internal consistency by disorder both cross-sectionally and over time. The criteria also retain their rank order of prevalence over time within the personality disorder category, despite personality disorder syndromal and criterion improvement (remission).

A key strength of the study was the inclusion of a large number of subjects with clinically significant personality disorders who were assessed with operational criteria by raters trained to reliable standards (24) and followed up by raters blind to prior diagnostic data. The shortcomings were that not all DSM-IV personality disorders were represented and that the results may not generalize to non-treatment-seeking personality disorder populations. With these strengths and limitations in mind, we present some implications that follow from the data.

The polythetic nature of the DSM-IV criteria for these disorders has often been criticized for its lack of a cohesive, prototypic hierarchy of characteristics and the fact that the system gives equal weight to criteria that may be less central to the personality disorder category they define. Indeed, we found differences among the criteria within each personality disorder—differences in prevalence and stability (or resistance to change) that reflect differences in the nature of the criteria that make up personality disorders. The criteria that are more frequent and enduring over time may reflect elements of personality or personality disorder that are closer to temperament and trait (constitutional proclivities to perceiving and acting/reacting). In contrast, those that are less pervasive and more changeable may be closer to symptomatic behaviors that are stress responsive and habitual (i.e., learned). The former relate more to nature, i.e., genetics and biology; the latter relate more to nurture and learning. The former may be prime targets for biological treatments; the latter, better targets for psychosocial interventions.

Hyman (25) has called for classifying personality disorders on the basis of dimensions that cut across existing categories within axis II and between axis II and axis I. Furthermore, Hyman suggested that the selection of particular dimensions should be based on “empirical factors such as heritability.” Our effort here was an attempt to identify potential core dimensions based on longitudinal prevalence and resistance to change as the parameters of external validity.

Based on these parameters, the criteria to emerge in borderline personality disorder were affective instability, anger, and impulsivity. These criteria reflect what others regard as core trait distortions or endophenotypes of borderline personality disorder, such as affective dysregulation/instability (26–32) or impulsive aggression (26, 32, 33). They reflect two dimensions that emerge recurrently in factor analyses of borderline personality disorder—dysregulated affect and dysregulated behavior (34, 35). They also reflect the time-varying course of the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study borderline personality disorder subjects, with affective dysregulation/instability associated with axis I major depressive disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder (36). It may be that these trait criteria are closer to the core of borderline personality disorder’s biogenetic structures. Furthermore, the less pervasive and more changeable criteria such as self-injury or frantic efforts to avoid abandonment may be seen as secondary or reactive, insofar as such behaviors represent attempts to adapt to, defend against, or cope with pathological affective dysregulation and impulsive aggression (37).

The trait-like criteria that emerged for avoidant personality disorder were regarding oneself as socially inept, feeling inadequate compared to others, and wanting evidence of being liked first before making social contacts. The common theme appears compatible with the internalizing dimension of anxious-misery identified by Kendler et al. (38), a dimension resulting largely from the effects of genetic risk factors. The criteria perhaps reflect the early temperaments of shyness and behavioral inhibition, temperaments that intermittently find symptomatic behavioral expression in a variety of avoidant behaviors (39).

The criteria that emerge as most common and trait-like for schizotypal personality disorder were paranoid ideation, ideas of reference, odd beliefs, and unusual experiences. These criteria probably represent milder variants of the cognitive distortion of reality that is central to the schizophrenia spectrum (40–42). In schizotypal personality disorder this distortion exists in attenuated form and only intermittently becomes expressed behaviorally as oddness or coldness.

Less is known or hypothesized concerning underlying trait dimensions for obsessive-compulsive personality disorder. In fact, our longitudinal criterion data may provide the first clues of the existence and nature of such dimensions. The most prevalent/least changeable obsessive-compulsive personality disorder criteria were rigidity, perfectionism, and problems delegating; these criteria highlight elements of withholding, resistance to change, and the need to control. Do they, perhaps, suggest traits relating to the neurobiology of aggressive control that are intermittently expressed behaviorally as miserliness and/or strict morality?

Our findings carry implications for criterion selection for borderline personality disorder, schizotypal personality disorder, avoidant personality disorder, and obsessive-compulsive personality disorder in DSM-V. Insofar as the concept of stability and resistance to change remains central to the generic definition of axis II, the criteria emerging as most prevalent and least changeable over time are prime candidates for retention. Criteria that are less common and more changeable may require more scrutiny, or they may need to offer other advantages in order to be retained. For example, self-injury is one of the least prevalent and most remitting criteria of borderline personality disorder, yet as a symptomatic behavior it has high visibility and substantial diagnostic efficiency (positive predictive power) cross-sectionally (10, 14), over time (unpublished 2004 study by C. M. Grilo et al.), and across ethnically diverse samples (17). Similarly, the criteria with the highest cross-sectional diagnostic positive predictive power are the symptomatic behaviors such as (observed) odd thinking for schizotypal personality disorder, avoids interpersonal situations for avoidant personality disorder, and concern with rules, details, and lists for obsessive-compulsive personality disorder (14). Clearly, the criteria for these disorders vary in their utility as they do in their source.

Our findings may also shed light on the longitudinal instability of these personality disorders as diagnostic entities (21, 22), that is, the symptomatic behavioral criteria “remit” more quickly and more frequently than trait criteria and are largely responsible for dips below the DSM diagnostic threshold for personality disorder. Such criteria may be good markers of disorder (e.g., the high diagnostic efficiency of self-injury for borderline personality disorder) but not good criteria for the assessment of stability of personality disorder pathology.

In conclusion, the DSM-IV criteria for schizotypal personality disorder, borderline personality disorder, avoidant personality disorder, and obsessive-compulsive personality disorder vary in their longitudinal prevalence and stability within disorder. This variation suggests that these DSM-IV personality disorders are hybrids of more stable traits and less stable symptomatic behaviors. The variation also suggests that both sets of criteria are key to defining personality disorders—one set highlighting personality, the other set highlighting disorder.

|

Received March 15, 2004; revision received May 17, 2004; accepted May 20, 2004. From the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study, Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior, Brown University, Providence, R.I.; the Department of Psychiatry, Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons and New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York; the Department of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School and McLean Hospital, Belmont, Mass.; and the Department of Psychiatry, Yale University School of Medicine and Yale Psychiatric Institute. Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. McGlashan, Yale University School of Medicine, 301 Cedar St., New Haven, CT 06519; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by NIMH grants MH-50837, MH-50838, MH-50839, MH-50840, and MH-50850, and by Senior Scientist Award MH-01654 to Dr. McGlashan.

1. Kernberg O: Borderline personality organization. J Psychoanal Assoc 1967; 15:641–685Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Grinker RR, Werble B, Drye R: The Borderline Syndrome. New York, Basic Books, 1968Google Scholar

3. Perry JC, Klerman GL: The borderline patient: a comparative analysis of four sets of diagnostic criteria. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1978; 35:141–152Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Klein D: Psychopharmacology and the borderline patients, in Borderline States in Psychiatry. Edited by Mack JE. New York, Grune & Stratton, 1975, pp 75–91Google Scholar

5. Stone MH: The Borderline Syndrome: Constitution, Coping, and Character. New York, Jason Aronson, 1978Google Scholar

6. Gunderson JG, Kolb JE: Discriminating features of borderline patients. Am J Psychiatry 1978; 135:792–796Link, Google Scholar

7. Spitzer RL, Endicott J, Gibbon M: Crossing the border into borderline personality and borderline schizophrenia: development of criteria. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1979; 36:17–24Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Millon T: Disorders of Personality: DSM-III, Axis II. New York, John Wiley, 1981Google Scholar

9. Widiger TA: DSM-IV reviews of the personality disorders: introduction to special series. J Personal Disord 1991; 5:122–134Crossref, Google Scholar

10. Gunderson J: DSM-IV personality disorders: final overview, in DSM-IV Sourcebook, Vol 4. Edited by Widiger TA, Frances AJ, Pincus HA, First MB, Davis W, Kline M. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1998, pp 1123–1140Google Scholar

11. Parker G, Roussos J, Wilhelm K, Mitchell P, Austin M-P, Hadzi-Pavlovic D: On modeling personality disorders: are personality style and disordered functioning independent or interdependent constructs? J Nerv Ment Dis 1998; 186:709–715Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Sanislow CA, McGlashan TH: Treatment outcome of personality disorders. Can J Psychiatry 1998; 43:237–250Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Hennen J, Silk KR: The longitudinal course of borderline psychopathology: 6-year prospective follow-up of the phenomenology of borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2003; 160:274–283Link, Google Scholar

14. Grilo CM, McGlashan TH, Morey LC, Gunderson JG, Skodol AE, Shea MT, Sanislow CA, Zanarini MC, Bender D, Oldham JM, Dyck I, Stout RL: Internal consistency, inter-criterion overlap and diagnostic efficiency of criteria sets for DSM-IV schizotypal, borderline, avoidant and obsessive-compulsive personality disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2001; 104:264–272Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Gunderson JG, Shea MT, Skodol AE, McGlashan TH, Morey LC, Stout RL, Zanarini MC, Grilo CM, Oldham JM, Keller M: The Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study, I: development, aims, design, and sample characteristics. J Personal Disord 2000; 14:300–315Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. McGlashan TH, Grilo CM, Skodol AE, Gunderson JG, Shea MT, Morey LC, Zanarini MC, Stout RL: The Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study: baseline axis I/II and II/II diagnostic co-occurrence. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2000; 102:256–264Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Grilo CM, Anez LM, McGlashan TH: The Spanish-language version of the Diagnostic Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders: development and initial psychometric evaluation of diagnoses and criteria. Compr Psychiatry 2003; 44:154–161Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Grilo CM., McGlashan TH: Convergent and discriminant validity of DSM-IV personality disorder criteria in adult outpatients with binge eating disorder. Compr Psychiatry 2000; 41:163–166Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Farmer RF, Chapman AL: Evaluation of DSM-IV personality disorder criteria as assessed by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders. Compr Psychiatry 2002; 43:285–300Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Morey LC, Skodol AE, Grilo CM, Sanislow CA, Zanarini MC, Shea MT, Gunderson JG, McGlashan TH: Temporal coherence of criteria for four personality disorders. J Personal Disord 2004; 18:394–398Crossref, Google Scholar

21. Shea MT, Stout R, Gunderson J, Morey LC, Grilo CM, McGlashan T, Skodol AE, Dolan-Sewell R, Dyck I, Zanarini MC, Keller MB: Short-term diagnostic stability of schizotypal, borderline, avoidant, and obsessive-compulsive personality disorders. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159:2036–2041Link, Google Scholar

22. Grilo CM, Sanislow CA, Gunderson JG, Pagano ME, Yen S, Zanarini MC, Shea MT, Skodol AE, Stout RL, Morey LC, McGlashan TH: Two-year stability and change in schizotypal, borderline, avoidant, and obsessive-compulsive personality disorders. J Consult Clin Psychol 2004; 72:767–775Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Chauncey DL, Gunderson JG: The Diagnostic Interview for Personality Disorders: interrater and test-retest reliability. Compr Psychiatry 1987; 28:467–480Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Zanarini MC, Skodol AE, Bender D, Dolan R, Sanislow C, Schaefer E, Morey LC, Grilo CM, Shea MT, McGlashan TH, Gunderson JG: The Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study: reliability of axis I and II diagnoses. J Personal Disord 2000; 14:291–299Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Hyman S: A new beginning for research on borderline personality disorder. Biol Psychiatry 2002; 51:933–935Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Siever LJ, Davis KL: A psychobiological perspective on the personality disorders. Am J Psychiatry 1991; 148:1647–1658Link, Google Scholar

27. Linehan MM: Understanding Borderline Personality Disorder. New York, Guilford, 1995Google Scholar

28. Livesley WJ, Jang KL, Vernon PA: Phenotypic and genetic structure of traits delineating personality disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998; 55:941–948Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Siever LJ, Torgersen S, Gunderson JG, Livesley WJ, Kendler KS: The borderline diagnosis, III: identifying endophenotypes for genetic studies. Biol Psychiatry 2002; 51:964–968Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Koenigsberg HW, Harvey PD, Mitropoulou V, Schmeidler J, New AS, Goodman M, Silverman JM, Serby M, Schopick F, Siever LJ: Characterizing affective instability in borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159:784–788Link, Google Scholar

31. Donegan NH, Sanislow CA, Blumberg HP, Fulbright RK, Lacadie C, Skudlarski P, Gore JC, Olson IR, McGlashan TH, Wexler BE: Amygdala hyperreactivity in borderline personality disorder: implications for emotional dysregulation. Biol Psychiatry 2002; 54:1284–1293Crossref, Google Scholar

32. Links PS, Heslegrave R, van Reekum R: Impulsivity: core aspect of borderline personality disorder. J Personal Disord 1999; 13:1–9Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Coccaro EF: Impulsive aggressive: a behavior in search of clinical definition. Harv Rev Psychiatry 1998; 5:336–339Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Sanislow CA, Grilo CM, McGlashan TH: Factor analysis of the DSM-III-R borderline personality disorder criteria in psychiatric inpatients. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:1629–1633Link, Google Scholar

35. Sanislow CA, Grilo CM, Morey LC, Bender DS, Skodol AE, Gunderson JG, Shea MT, Stout RL, Zanarini MC, McGlashan TH: Confirmatory factor analysis of DSM-IV criteria for borderline personality disorder: findings from the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159:284–290Link, Google Scholar

36. Shea MT, Stout RL, Yen S, Pagano ME, Skodol AE, Morey LC, Gunderson JG, McGlashan TH, Grilo CM, Sanislow CA, Bender DS, Zanarini MC: Associations in the course of personality disorders and axis I disorders over time. J Abnorm Psychol 2004; 113:499–508Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Links PS, Boggild A, Sarin N: Modeling the relationship between affective lability, impulsivity, and suicidal behavior. J Psychiatr Pract 2000; 6:247–255Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Kendler KS, Prescott CA, Myers J, Neale MC: The structure of genetic and environmental risk factors for common psychiatric and substance use disorders in men and women. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003; 60:929–937Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Schwartz CE, Wright CI, Shin LM, Kagan J, Rauch SL: Inhibited and uninhibited infants “grown up”: adult amygdalar response to novelty. Science 2003; 20:1952–1953Crossref, Google Scholar

40. Liddle PF, Barnes TR: Syndromes of chronic schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry 1990; 157:558–561Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41. Fenton WS, McGlashan TH: Natural history of schizophrenia subtypes. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48:978–986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

42. McGlashan TH: The schizophrenia spectrum concept. Advances in Neuropsychiatry and Psychopharmacology 1991; 1:193–200Google Scholar