Is Combination Olanzapine and Antidepressant Medication Associated With a More Rapid Response Trajectory Than Antidepressant Alone?

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The authors’ goal was to determine if prescription of antidepressant medication plus olanzapine initiates a more rapid response than prescription of antidepressant alone. METHOD: Twenty patients with major depression were studied. For 2 weeks the patients were blindly assigned to receive antidepressant plus olanzapine or antidepressant plus placebo. After 2 weeks, olanzapine augmentation was initiated for patients who did not improve with placebo augmentation. Response to medication was measured primarily by Hamilton Depression Rating Scale score. Other measures were the CORE, Clinical Global Impression, Beck Depression Inventory, and Daily Rating Schedule. RESULTS: Hamilton depression scores improved nonsignificantly in response to olanzapine combination therapy, but that trend was not evident on any secondary measure. Four patients who did not improve while receiving antidepressant and placebo showed rapid remission following late olanzapine augmentation. CONCLUSIONS: Failure to demonstrate any benefit from initial combination therapy may reflect an underpowered rather than a negative study. The distinct impact of late olanzapine augmentation suggests that pretreatment with an antidepressant may be required to facilitate a rapid antidepressant response to combined treatment.

The addition of an augmenting atypical antipsychotic drug to an antidepressant drug is an increasingly observed clinical practice. Rapid remission has been described in relation to olanzapine (1) and risperidone (2) augmentation. In a controlled study (3), subjects with treatment-resistant depression received olanzapine alone, fluoxetine alone, or a combination of both; the combination was associated with significantly greater and faster improvement than was either drug alone.

Such data encouraged the current study, which tests the hypothesis that prescription of olanzapine with antidepressant medication is associated with a more rapid remission of depression than prescription of an antidepressant alone. Because there is evidence suggesting that, when antidepressants “work,” clinical improvement is present in the first 10 days (4), the controlled study component was restricted to 2 weeks.

Method

The study was conducted in an outpatient practice (G.P.); the inclusion criterion was that the patient be experiencing a first or new episode of DSM-IV nonpsychotic major depression warranting prescription of antidepressant medication. Patients could not have received any antidepressant medication in the preceding 2 weeks or ECT in the previous month. If a patient had previously responded well to a particular antidepressant, that antidepressant was likely to be prescribed again (or the converse). If the patient had never received medication, dual-action antidepressants were favored for melancholic depression and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) were favored for nonmelancholic depression.

The active augmentor contained 2.5 mg of olanzapine, initially one tablet at night but allowed to be raised to two tablets at night if there was no significant improvement or side effects over the first week. At 2 weeks, the blind could be broken. If the patient was then in complete remission, the augmentor was ceased. If the patient showed minimal or no improvement to identified placebo augmentation, olanzapine augmentation could then be initiated.

At baseline, depression severity was rated on the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (5) (the primary outcome measure) and psychomotor severity was rated on the CORE (6). At weekly intervals, these measures were repeated and Clinical Global Impression (CGI) estimates of improvement (% change from baseline) undertaken. Patients completed the Beck Depression Inventory (7) at baseline and weekly as well as a Daily Rating Schedule (8) assessing depression severity nightly.

Of 24 subjects approached, three declined and one dropped out after 1 week. The remaining 20 subjects form the study group; 10 were assigned blindly (by means of random numbering) to receive antidepressant plus olanzapine, and 10 were assigned to receive antidepressant plus placebo. The antidepressants prescribed were extended release venlafaxine in the morning (N=10), citalopram in the morning (N=5), mirtazapine at night (N=4), and sertraline in the morning (N=1). Patients’ antidepressant medication regimens were maintained for 4 weeks without initiation of any other psychotropic medication. When the blind was broken at 2 weeks, the four recipients of placebo augmentation judged clinically to be nonimprovers received late olanzapine augmentation (at a dose of 2.5–5.0 mg).

Analyses were conducted on an intent-to-treat basis, and the last observation carried forward strategy was employed.

Results

Seven of the patients were men and 13 were women; their mean age was 49.5 years (SD=14.5). Respective 2-week and 4-week improvement rates were 50% and 73% (Hamilton depression scale), 49% and 67% (Beck Depression Inventory), 41% and 71% (CORE), 44% and 68% (total Daily Rating Schedule), and 44% and 73% (CGI improvement).

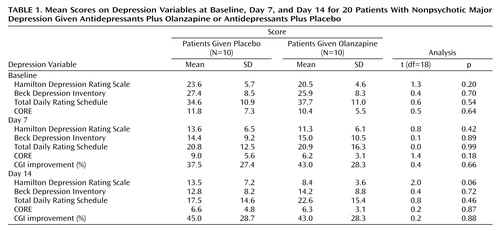

Table 1 reports baseline, day 7, and day 14 data for the patients receiving either olanzapine or placebo augmentation over the first 2 weeks. Over that fortnight, the former improved by 59.0% on the Hamilton depression scale (compared with 42.8% for those receiving placebo augmentation), a nonsignificant (t=2.0) difference. In addition, we defined primary responders as having at least 50% improvement in Hamilton depression scale scores over that fortnight. Of the 12 primary responders, eight were in the olanzapine and four in the placebo augmentation group, a nonsignificant (t=3.3, p=0.07) difference favoring olanzapine augmentation. However, because analyses failed to identify any significant impact of olanzapine augmentation on any other outcome study variable at that 2-week review, we analyzed percentage improvement on each Hamilton depression scale item to determine if the primary measure trends might merely be an artifact of olanzapine acting on selective constructs such as sleep. No such selectivity was evident: patients receiving olanzapine augmentation tended to show greater improvement on 13 of the 17 items, without any suggested superior impact on sleep.

For the four subjects receiving initial placebo and late olanzapine augmentation following minimal response at 2 weeks, improvement (from baseline) was distinctive by day 21 (i.e., 79.7% on the Hamilton depression scale, 86.4% on the Beck Depression Inventory, 82.1% on the total Daily Rating Schedule, and 83.3% improvement on CGI) and extended by day 28. Specifically, their mean weekly Hamilton depression scale scores were 25.2, 17.7, 18.0, 4.7, and 3.0, and their respective mean Beck Depression Inventory scores were 21.2, 17.7, 14.0, 3.0, and 1.7, with the trend breaks between weeks 2 and 3 following late olanzapine augmentation.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study examining whether initial prescription of an atypical antipsychotic and an antidepressant together is associated with a more rapid antidepressant effect. In the light of the small number of subjects, it remains a pilot study but should assist combination and augmentation therapy study designs.

Improvement of some 50% over the first 2 weeks was so high as to risk reducing the probability of any true olanzapine augmentation benefit being revealed. The nonsignificant findings that patients receiving concomitant olanzapine and antidepressant were more likely to achieve responder status (i.e., 80% versus 40%) and have lower Hamilton depression scale scores at day 14 were not mirrored in the other observer-rated measures (CORE and CGI improvement) and are therefore unlikely to reflect rater bias. The findings may reflect nuances of the Hamilton depression scale detecting a true effect in an underpowered study.

Again conceding the small number of subjects, we highlight the suggestion of a distinct and rapid olanzapine augmenting effect in the patients who initially received antidepressant alone without benefit and, compatible with earlier observations (1–3), in treatment-resistant patients. Thus, any distinct olanzapine augmentation effect may depend on the antidepressant drug being in place—a mechanism postulated to explain lithium augmentation of antidepressant drugs in unipolar depression. De Montigny et al. (9), describing a case series of eight patients who, having failed to respond to a tricyclic, then responded rapidly to lithium introduction, suggested that tricyclic pretreatment sensitized the serotonin (5-HT) receptor to create an antidepressant effect, with lithium increasing the efficacy of the central 5-HT system. Such a model may account for the substantive antidepressant responses reported when atypical antipsychotic drugs are added to antidepressant drugs in patients not responding to the antidepressant drug alone.

Such results argue for further refined studies examining the impact of both simultaneous prescription and prescription sequencing studies involving differing antidepressant classes, because the broader action of atypical antipsychotic drugs like olanzapine (with effects on noradrenergic, dopaminergic and serotonergic neurotransmission) may produce quite different results when combined with narrow-action SSRIs than when combined with broader-action antidepressants.

|

Received April 20, 2004; revision received June 17, 2004; accepted July 7, 2004. From the School of Psychiatry, University of New South Wales. Address reprint requests and correspondence to Professor Parker, Black Dog Institute, Prince of Wales Hospital, Randwick, Australia 2031; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by National Health and Medical Research Council Program Grant 2223208 and by an Investigator Initiated Grant from Eli Lilly, Australia.

1. Parker G: Olanzapine augmentation in the treatment of melancholia: the trajectory of improvement in rapid responders. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2002; 17:87–89Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Ostroff RB, Nelson JC: Risperidone augmentation of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in major depression. J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 60:256–259Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Shelton RC, Tollefson GD, Tohen M, Stahl S, Gannon KS, Jacobs TG, Buras WR, Bymaster FP, Zhang W, Spencer KA, Feldman PD, Meltzer HY: A novel augmentation strategy for treating resistant major depression. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:131–134Link, Google Scholar

4. Parker G: On brightening up: triggers and trajectories to recovery from depression (editorial). Br J Psychiatry 1996; 168:263–264Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Hamilton M: A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1960; 23:56–62Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Parker G, Hadzi-Pavlovic D (eds): Melancholia: A Disorder of Movement and Mood. New York, Cambridge University Press, 1996Google Scholar

7. Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J: An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1961; 4:561–571Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Parker G, Roy K: The development of a six-item daily self-report measure assessing identified depressive domains. J Affect Disord 2003; 73:289–294Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. De Montigny C, Grunberg F, Mayer A, Deschenes JP: Lithium induces rapid relief of depression in tricyclic antidepressant drug non-responders. Br J Psychiatry 1981; 138:252–256Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar