Genetic and Environmental Sources of Covariation Between Generalized Anxiety Disorder and Neuroticism

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The authors examined the sources of covariation between generalized anxiety disorder and the personality trait of neuroticism. Because women have higher levels of neuroticism and twice the risk of lifetime generalized anxiety disorder of men, gender-specific effects were also explored. METHOD: Lifetime generalized anxiety disorder and neuroticism were assessed in more than 8,000 twins from male-male, female-female, and opposite-sex pairs through structured diagnostic interviews. Sex-limited Cholesky structural equation models were used to decompose the correlations between generalized anxiety disorder and neuroticism into genetic and environmental components, including sex-specific factors. RESULTS: Genetic correlations between generalized anxiety disorder and neuroticism were high and differed (nonsignificantly) between men and women (1.00 and 0.58, respectively). When nonsignificant gender differences were removed from the models, correlations between generalized anxiety disorder and neuroticism were estimated at 0.80 (95% confidence interval=0.52–1.00). The individual-specific environmental correlation between generalized anxiety disorder and neuroticism was estimated at 0.20 for both genders. CONCLUSIONS: There is substantial overlap between the genetic factors that influence individual variation in neuroticism and those that increase liability for generalized anxiety disorder, irrespective of gender. The life experiences that increase vulnerability to generalized anxiety disorder, however, have only modest overlap with those that contribute to an individual’s level of neuroticism.

Free-floating generalized anxiety was a prominent feature in Freud’s psychoanalytic theories and the central feature of his “anxiety neurosis” (1). DSM-I, the foundation of which was largely based on psychoanalytic thinking, characterized anxiety as the “hallmark” of neurotic disorders. Generalized anxiety disorder first made its appearance as a syndrome separate from panic disorder in the Research Diagnostic Criteria (2) as a refinement of the earlier concept of “anxiety neurosis” and was subsequently included in DSM-III. Research into generalized anxiety disorder as a distinct entity suggested revisions in the diagnostic criteria that were incorporated into DSM-III-R and DSM-IV, which have improved the nosological status of generalized anxiety disorder. However, its diagnosis remains controversial since some authors contend that generalized anxiety disorder may not represent an autonomous syndrome but rather a nonspecific cluster of “residual” anxiety symptoms stemming from other disorders (3), although others believe it is better characterized as an anxious temperament type (4) or a vulnerability to developing other anxiety or mood disorders (5).

Neuroticism, on the other hand, has enjoyed a well-accepted role in the characterization of personality traits. Reflecting a tendency toward states of negative affect (6), it, together with extroversion and psychoticism, constituted the three key dimensions of personality, according to Eysenck and Eysenck (7), and has been included in nearly all theories of personality since its introduction. It possesses good psychometric properties of item and construct validity, stability, and cross-cultural validation. Gray and McNaughton (8) contended that anxiety proneness is primarily captured by measures of neuroticism, together with smaller contributions from the dimension of extraversion.

Generalized anxiety disorder and neuroticism have considerable overlap in their descriptive features. Generalized anxiety disorder is a clinical disorder characterized by excessive, chronic worry regarding multiple areas of life as the central feature distinguishing it from other anxiety and mood disorders. DSM-IV requires at least three of six associated symptoms of restlessness, fatigue, concentration difficulty, irritability, muscle tension, and sleep disturbance for a minimal duration of 6 months, while DSM-III-R also included other somatic symptoms related to motor tension or autonomic hyperactivity. Also required is a hierarchical diagnostic exclusion from mood, psychotic, and pervasive developmental disorders, exclusion of an “organic” etiology (substance use or a medical condition), and the occurrence of clinically significant distress or impairment because of the anxiety (DSM-IV only). Neuroticism, as assessed with the short form of the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire (9), contains 12 items that overlap with some of the diagnostic criteria for generalized anxiety disorder, such as irritability, nervousness, worrying, and feeling tense. A total score (range=0–12) is obtained by adding the number of items endorsed by the subject. It does not have duration or impairment requirements.

What is the relationship between generalized anxiety disorder and neuroticism? High levels of neuroticism have been observed in patients with depressive and anxiety disorders. Most studies find higher than average neuroticism in women than men, and the lifetime prevalence of generalized anxiety disorder in women is about twice that of men. Twin and family studies of generalized anxiety disorder have found significant familial aggregation that is largely accounted for by genetic factors of moderate effect (10), while several twin studies have estimated the heritability of neuroticism ranging from 0.3 to 0.6, with little or no role for the family environment (11–13). One large population-based twin study that examined neuroticism and self-report symptoms of anxiety and depression (14) concluded that genetic variation in these symptoms is largely dependent on the same factors as those that affect neuroticism.

In this study, we sought to determine the sources of individual covariation between the semiquantitative personality trait of neuroticism and the psychiatric illness of generalized anxiety disorder. Specifically, we examined to what extent neuroticism and generalized anxiety disorder share the same genetic risk factors, environmental risk factors, or both. In addition, we explored the potential sources of sex differences in these shared risk factors.

Method

Subjects

The twins in this report derive from two interrelated projects using the population-based Virginia Twin Registry—formed from a systematic review of all birth certificates in the Commonwealth of Virginia—that now constitutes part of the Mid-Atlantic Twin Registry. The details of the samples in these two projects are described elsewhere (15). This study results from the fourth interview wave with the sample of twins from white female-female pairs and the second interview wave with the sample of white male-male and male-female pairs. In the fourth interview with female-female pairs, we assessed, through telephone interviews, both members of 832 pairs, 505 of whom were monozygotic and 327 of whom were dizygotic. The mean age of the participating twins in this interview was 36.3 years (SD=8.2) and ranged from 21 to 62. From the second interview with the male-male and male-female pairs sample, we interviewed both members of 708 male-male monozygotic pairs, 491 male-male dizygotic twins, and 1,070 opposite-sex male-female dizygotic pairs. Face-to-face interviews were conducted in 80% of this sample, with the remaining interviews conducted by telephone. At the time of the interviews, subjects ranged in age from 20 to 58 years, with a mean of 36.9 years (SD=9.1). This project was approved by the Committee for the Conduct of Human Research at Virginia Commonwealth University. Written informed consent was obtained before face-to-face interviews, and verbal consent was obtained before phone interviews.

As outlined previously (16), in the female-female sample, zygosity was initially determined by a blind review of two experienced twin researchers that used standard questions (11) and photographs. Blood samples were obtained from both members of 119 pairs of uncertain zygosity and analyzed by using eight restriction fragment length polymorphism markers (17). More recently, we have performed polymerase chain reaction (PCR) zygosity tests on an additional 269 twin pairs, oversampling those for whom our prior zygosity assignment was questionable. On the basis of these tests (where the mean number of markers tested per pair was 17.5, SD=8.4), zygosity was changed for 12 pairs (4.5% of those tested). In the male-male and male-female sample, zygosity was initially determined by an algorithm based on standard questions and validated against the zygosity diagnoses in the female-female sample. Application of the algorithm to this male sample was validated by an analysis of PCR polymorphisms (mean of 11.5 markers per pair, SD=11.9) in a random sample of 196 twin pairs with an error rate of 5.1%.

Measures

Neuroticism was assessed with the 12 items from the short form of the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire by means of a self-report questionnaire. It was analyzed as an ordinal variable with scores from 0 to 12. Lifetime generalized anxiety disorder was assessed through telephone and face-to-face structured psychiatric interviews based on the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (18). However, we assessed the last-year history of generalized anxiety disorder and a lifetime history of generalized anxiety disorder before the last year in two separate sections, combining these to estimate lifetime generalized anxiety disorder. DSM-IV hierarchy rules with major depression differentiated those affected with a full overlap of generalized anxiety disorder and major depressive episodes (i.e., the two syndromes always occurred contemporaneously) from those with no or only partial overlap. Interviewers, who were carefully trained and supervised, had at least a master’s degree in a mental-health-related field or a bachelor’s degree in such a field and 2 years of clinical experience. Two senior staff reviewed each interview for completeness and consistency. Data were entered twice to minimize data-entry errors. Members of a twin pair were interviewed by different interviewers who were blind to clinical information about the co-twin. For a subset of the subjects chosen at random (about 400 in total), we performed a second identical diagnostic assessment 2 to 6 weeks after the base interview by an independent interviewer who was blind to information from the first interview. This provided an estimate of reliability for generalized anxiety disorder.

Due to the relatively low prevalence of strictly defined generalized anxiety disorder (1%–3%), the statistical power necessary to perform model fitting was poor (19). In particular, the use of a 6-month minimal duration resulted in unstable estimates of twin resemblance, especially for the male-male pairs. To overcome this, we instead used a previously defined (broad generalized anxiety disorder) phenotype that requires the core aspects of chronic worry and anxiety, the requisite minimum three of six DSM-IV-associated symptoms, and hierarchical exclusion rules with major depression but with a minimum duration of 1 month instead of 6. This increased the lifetime prevalence rates to 12% for the men and 18% for the women. Our prior analyses indicated that within the limits of our statistical power, the overall pattern of results for the narrow and broad definitions of generalized anxiety disorder did not differ (20). We retained hierarchy rules with major depression to ensure that the covariation we were studying was primarily between neuroticism and generalized anxiety disorder and not major depression.

Statistical Analysis

For neuroticism, we examined the internal consistency of the 12 items that make up the short form of Eysenck Personality Questionnaire by means of Cronbach’s alpha. Gender differences in mean neuroticism were tested with the t statistic. We estimated the reliability of generalized anxiety disorder diagnoses by using the kappa coefficient.

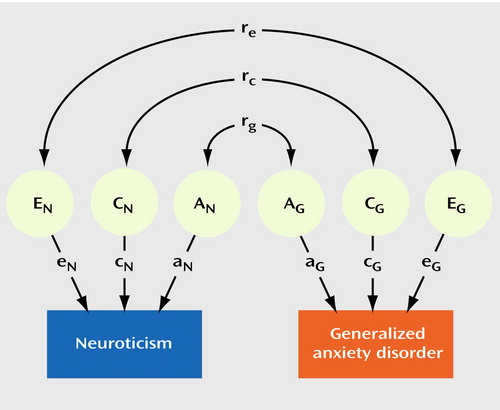

We applied a sex-limited bivariate Cholesky structural equation model to the twin data to assess genetic and environmental liabilities shared between neuroticism and generalized anxiety disorder (21). The bivariate Cholesky model imposed a stratified structure on the latent factors hypothesized to determine the measured phenotypes, with one set of factors (additive genetic A1, common familial environmental C1, and individual-specific environmental E1) influencing both neuroticism and generalized anxiety disorder and the second set (A2, C2, and E2) accounting for residual influences specific to generalized anxiety disorder (i.e., not shared with neuroticism). This choice of ordering was based upon the a priori hypothesis that generalized anxiety disorder may have specific risk factors over and above those shared with neuroticism. Sex-limitation models tested for two types of gender differences: 1) differences in the magnitude of effects of the same underlying latent (genetic and environmental) factors and 2) different sources of effects not shared between men and women (e.g., sex-specific genes). A reparameterization of the model in terms of correlations is schematically depicted in Figure 1. (For simplicity, only one twin is represented, and sex-specific effects are not illustrated.) In this model, the phenotypic correlation between neuroticism and generalized anxiety disorder in an individual was decomposed into the additive genetic (rg), common familial environmental (rc), and individual-specific environmental (re) correlations between those latent factors.

We fit models to the raw data by using the Mx statistical modeling program (22). Model testing began with the full (additive genetic, common environmental, and individual-specific environmental) model that included all of the sources of variance indicated in Figure 1. Model parameters and indices that characterized the fit of the model were calculated, and then this model was compared with nested submodels created by eliminating or constraining parameters in a stepwise fashion. The goal was to seek the most parsimonious genetic architecture that sufficiently described the data while allowing for sources of gender differences that were tested by means of restricted submodels. The fit of nested submodels was compared by taking the difference between –2 times the log likelihood (–2LL) for the full model and submodel, which is distributed as a chi-square distribution with degrees of freedom equal to the difference of degrees of freedom of the two models. Model fit was evaluated according to the principle of parsimony. More parsimonious models with fewer parameters are considered preferable if they do not provide a significantly worse fit. We operationalized parsimony by using the Akaike information criterion statistic (23), calculated as the model chi-square minus two times the degrees of freedom, with lower values of Akaike information criterion providing an improved balance of model fit and complexity.

Results

In our sample, the mean neuroticism score for women (3.289) was significantly higher than for men (3.046) (pooled t statistic=3.34, df=7206, p=0.0009). The 12 items from the short form of the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire that make up the total score exhibited good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha=0.84). The reliability of our broad, 1-month generalized anxiety disorder diagnosis was quite low (kappa=0.34) but comparable to the 6-month DSM-based definition (kappa=0.25).

Table 1 depicts the polychoric correlation matrices for neuroticism and generalized anxiety disorder in male and female same-sex monozygotic and same- and opposite-sex dizygotic twins. Monozygotic correlations are listed above and dizygotic below each shaded diagonal, respectively. There was substantial within-twin correlation between neuroticism and generalized anxiety disorder (0.2–0.4), corresponding to the often-observed covariation of neuroticism and generalized anxiety disorder within subjects. A higher overall monozygotic than dizygotic cross-twin correlation between neuroticism and generalized anxiety disorder suggested that genetic factors play a role in their covariation, just as higher monozygotic than dizygotic resemblance for a single trait occurs because monozygotic twins share 100% of their genes in common compared to only an average 50% for dizygotic twins. Also, this effect appears slightly larger in men, indicating that the genes accounting for the covariation of neuroticism and generalized anxiety disorder may have a greater impact on men. In addition, smaller cross-twin dizygotic correlations between neuroticism and generalized anxiety disorder and between the opposite sex and the same sex suggest a possible role for sex-specific factors.

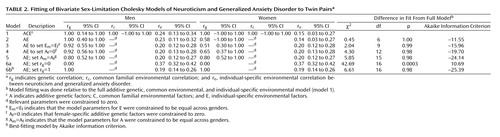

Table 2 illustrates the results of our model-fitting procedure. The full model (model 1) included additive genetic, common environmental, and individual-specific environmental sources of variance and covariance for neuroticism and generalized anxiety disorder, with both male-female shared and sex-specific genetic factors. Estimates for rg, rc, and re were 1.00, 1.00, and 0.24 for the men and 1.00, 1.00, and 0.15 for the women, respectively, with wide confidence intervals. Model 2 constrained the common environmental sources of variance to zero since these are estimated to be zero or almost zero for both neuroticism and generalized anxiety disorder in both sexes, as had been observed in univariate analyses for these variables previously. This model was essentially identical in goodness of fit but with a lower (i.e., more negative) Akaike information criterion. This also produced nearly the same estimates for the correlations except for a reduction in the female genetic correlation (0.58) and a smaller confidence interval for the male genetic correlation. We constrained the magnitude of the individual specific environment to be equal across genders in model 3 without significant difference in model fit, as suggested by the similarity of their point estimates. This produced minor fluctuations in the point estimates of the correlations. Model 4 tested the significance of evidence for sex-specific genes by setting their path loadings to zero. This resulted in a nonsignificant deterioration in fit and a more negative Akaike information criterion compared to model 3 and was, thus, more preferable. Model 5 then tested whether the magnitude of the additive genetic sources of covariation between neuroticism and generalized anxiety disorder differed between men and women by constraining male and female model parameters to be equal, again resulting in a model with a more negative Akaike information criterion. Models 6a and 6b tested the alternative hypotheses that neuroticism and generalized anxiety disorder share none (rg=0) or all (rg=1) of their genes in common. Model 6a had a significantly poorer fit to the data compared to model 5 (Δχ2=36.84, df=1, p<0.0001), while model 6b fit the data almost as well as model 5 but with slightly more negative Akaike information criterion, making it the overall best-fitting model by that criterion.

Discussion

This study used bivariate modeling of twin data to examine the genetic and environmental risk factors shared by the personality trait of neuroticism and the psychiatric illness generalized anxiety disorder. Our results suggest that the genetic factors underlying neuroticism are nearly indistinguishable from those that influence liability to generalized anxiety disorder. Environmental risk factors, on the other hand, are only modestly correlated between neuroticism and generalized anxiety disorder. By applying the sex-limitation structure to these models in both same-sex and opposite-sex twin pairs, we attempted to determine whether this was dependent on gender. While the genetic correlation between neuroticism and generalized anxiety disorder was estimated to be (nonsignificantly) smaller in women than in men, our findings apply equally to men and women.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the factors underlying the relationship between neuroticism and generalized anxiety disorder. Previous analyses have examined the effects of genes and the environment for neuroticism and generalized anxiety disorder separately. The most detailed findings for neuroticism came from two large-scale twin/family studies. They reported both additive and nonadditive genetic factors for neuroticism, no significant contribution from shared environment, and sex differences in the magnitude but not the source of genetic effects (i.e., the same genes are expressed differently in men and women). Our sample did not possess the statistical power to significantly detect nonadditive genetic factors or sex differences, although the latter were suggested. In a prior analysis in our sample, we did not detect gender differences in genetic or environmental factors for generalized anxiety disorder (20). A large, population-based study of Australian twins that examined the covariation between neuroticism and current depression and anxiety symptom scores reported genetic correlations between neuroticism and anxiety scores of about 0.8 in both sexes (14).

Our group had previously performed a similar analysis of neuroticism and major depressive disorder in this sample (24). In that study, the within-sex genetic correlations between neuroticism and major depression were estimated at 0.68 for men and 0.49 for women, with this model fitting only slightly better than one with a correlation between neuroticism and major depression of 0.55 for both sexes. In addition, the correlations between neuroticism and major depression were significantly different from 1.00. This suggests that although major depression and generalized anxiety disorder have a genetic correlation near unity (25), some differences in their correlation with neuroticism may exist. This is not inconsistent since a study that uses a semiquantitative variable such as neuroticism has greater statistical power to detect differences than one that uses only dichotomous variables such as major depression and generalized anxiety disorder (19).

There are several potentially important implications of our findings. First, neuroticism and generalized anxiety disorder share a significant proportion of their liability genes in common but only a modest proportion of individual environmental risk factors. Such a high correlation with the genes for neuroticism may have implications regarding generalized anxiety disorder’s place in psychiatric nosology. Is generalized anxiety disorder better characterized as an anxious personality type that belongs on axis II, as some have speculated (4), or rather, is generalized anxiety disorder an axis I syndrome that develops from the same liability genes as those for neuroticism but with different predisposing life events? Given the shorter, modified duration criteria for generalized anxiety disorder used in these analyses and the design of this study, we are unable to adequately address the hypotheses herein. Second, our findings of the same or a higher genetic correlation between neuroticism and generalized anxiety disorder in men do not support the hypothesis that the relationship between higher levels of neuroticism and rates of generalized anxiety disorder in women may be explained by a greater sharing of genetic risk factors in women. Finally, several groups have proposed using neuroticism as a quantitative intermediate or “endo” phenotype in molecular genetic investigations of depressive and anxiety disorders (26) based upon either phenotypic studies of the overlap between levels of neuroticism and these disorders or twin study findings of high genetic correlation between neuroticism and symptom scores. While this study was not designed to test the endophenotypic hypothesis directly, our findings suggest that neuroticism may serve as a useful target in identifying liability genes for generalized anxiety disorder. This has increasing relevance because both association (27) and linkage studies (28) have identified putative genetic regions that influence individual variation in neuroticism.

The results of this analysis should be interpreted in the context of several potential limitations. First, we used a broadened DSM-IV definition of generalized anxiety disorder with a 1-month minimum duration in order to increase the prevalence and maximize our power to estimate model parameters. Although we have previously shown that this modification does not substantively change genetic modeling for generalized anxiety disorder as long as the diagnostic hierarchy with major depression is preserved (20), we felt it prudent to examine the effects of these changes on the present analyses. Neither increasing the minimal duration to the usual 6 months nor using the narrow DSM-IV criteria produced significantly different results from those presented here. Estimates for rg and re varied somewhat from one analysis to another because of the lower statistical power, but the overall findings remained the same. The same was true when DSM-III-R-associated symptom criteria were substituted for those from DSM-IV. Thus, our findings do not strongly depend upon the definition we chose to use in our analyses.

Second, although the genetic correlation between neuroticism and generalized anxiety disorder may be higher in men than women, our sample did not possess the statistical power to confirm this. Thus, despite the size of our sample, we were limited in our ability to detect sex differences in the factors underlying the covariation of neuroticism and generalized anxiety disorder. The finding of gender differences in the genetic correlation, if replicated, may have important implications for identifying genes for generalized anxiety disorder in the two sexes when using neuroticism as an endophenotype.

Third, the findings of this analysis are predicated on the assumptions of the method used, that is, the structural equation modeling of twins. These assumptions include the independence and additivity of the latent variables, the absence of assortative mating, and equal correlation in monozygotic and dizygotic twins for environmental experiences of relevance to the trait under study (21). If the latter, known as the equal environment assumption, is violated, higher monozygotic similarity could potentially result from increased monozygotic environmental similarity instead of higher genetic similarity. While we have not detected such violations for generalized anxiety disorder in this sample (20), this cannot be ruled out for neuroticism. Differences in heritability estimates of neuroticism from twin and adoption studies have in the past been attributed to either violations of the equal environment assumption or nonadditive genetic effects (29), with the latter seeming more likely, given their unambiguous detection in the large twin/family studies cited.

Fourth, neuroticism and lifetime history of generalized anxiety disorder were assessed at one time point, which potentially confounds the effects of individual-specific environment and measurement error, reducing the corresponding estimates of genetic effects. For example, we have found, for major depression in our female-female sample, that improving the diagnostic reliability by reducing error by means of multiple sequential assessments increased the heritability estimate substantially (30). This measurement “noise” may also have the effect of reducing the correlations between neuroticism and generalized anxiety disorder—in particular, the individual-specific environmental correlation, re. Given the low reliability we found for generalized anxiety disorder, this may have a substantial effect on our results. If this is the case, our analysis may have underestimated re.

Fifth, because the sample was made up entirely of Caucasians, these results may not generalize to other ethnic groups.

|

|

Received March 27, 2003; revision received Oct. 28, 2003; accepted Nov. 4, 2003. From the Department of Psychiatry, Virginia Institute for Psychiatric and Behavioral Genetics, Virginia Commonwealth University. Address reprint requests to Dr. Hettema, Department of Psychiatry, Virginia Institute for Psychiatric and Behavioral Genetics, P.O. Box 980126, Richmond, VA 23298-0126; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by an NIMH Mentored Clinical Scientist Development Award (1-K08-MH-66277-1) to Dr. Hettema and grants (MH-40828, AA-09095, DA-11287, and MH/AA/DA-49492) to Dr. Kendler. The authors acknowledge the contribution of the Virginia Twin Registry, now part of the Mid-Atlantic Twin Registry, to the ascertainment of subjects for this study. The Mid-Atlantic Twin Registry, directed by Drs. L. Corey and L. Eaves, has received support from the National Institutes of Health, the Carman Trust, and the W.M. Keck, John Templeton, and Robert Wood Johnson Foundations. The authors thank Michael C. Neale, Ph.D., for assistance in model construction and interpretation.

Figure 1. Bivariate Twin Model for Neuroticism and Generalized Anxiety Disordera

aThe phenotypic correlation is decomposed into the additive genetic correlation (rg) between additive genetic factors (AN and AG), the common environmental correlation (rc) between common familial environmental factors (CN and CG), and the individual-specific environmental correlation (re) between individual-specific environmental factors (EN and EG) for neuroticism and generalized anxiety disorder, respectively.

1. Freud S: The justification for detaching from neurasthenia a particular syndrome: the anxiety-neurosis (1894), in Collected Papers, vol 1. Edited by Jones E, translated by Riviere J. New York, Basic Books, 1959, pp 76–106Google Scholar

2. Spitzer RL, Endicott J, Robins E: Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC) for a Selected Group of Functional Disorders, 2nd ed. New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1975Google Scholar

3. Breier A, Charney DS, Heninger GR: The diagnostic validity of anxiety disorders and their relationship to depressive illness. Am J Psychiatry 1985; 142:787–797Link, Google Scholar

4. Akiskal HS: Toward a definition of generalized anxiety disorder as an anxious temperament type. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 1998; 393:66–73Medline, Google Scholar

5. Brown TA, Barlow DH, Liebowitz MR: The empirical basis of generalized anxiety disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:1272–1280Link, Google Scholar

6. Costa PT Jr, McCrae RR: Influence of extraversion and neuroticism on subjective well-being: happy and unhappy people. J Pers Soc Psychol 1980; 38:668–678Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Eysenck HJ, Eysenck MJ: Personality and Individual Differences: A Natural Science Approach. New York, Plenum, 1985Google Scholar

8. Gray JA, McNaughton N: The Neuropsychology of Anxiety, 2nd ed. Oxford, UK, Oxford University Press, 2000Google Scholar

9. Eysenck HJ, Eysenck SBG: Eysenck Personality Questionnaire Manual. London, Hodder and Stoughton, 1975Google Scholar

10. Hettema JM, Neale MC, Kendler KS: A review and meta-analysis of the genetic epidemiology of anxiety disorders. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:1568–1578Link, Google Scholar

11. Eaves LJ, Eysenck HJ, Martin NG: Genes, Culture and Personality: An Empirical Approach. Oxford, UK, Oxford University Press, 1989Google Scholar

12. Eaves LJ, Heath AC, Neale MC, Hewitt JK, Martin NG: Sex differences and non-additivity in the effects of genes on personality. Twin Res 1998; 1:131–137Medline, Google Scholar

13. Lake RI, Eaves LJ, Maes HH, Heath AC, Martin NG: Further evidence against the environmental transmission of individual differences in neuroticism from a collaborative study of 45,850 twins and relatives on two continents. Behav Genet 2000; 30:223–233Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Jardine R, Martin NG, Henderson AS: Genetic covariation between neuroticism and the symptoms of anxiety and depression. Genet Epidemiol 1984; 1:89–107Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Kendler KS, Prescott CA: A population-based twin study of lifetime major depression in men and women. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999; 56:39–44Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Kendler KS, Neale MC, Kessler RC, Heath AC, Eaves LJ: A population-based twin study of major depression in women: the impact of varying definitions of illness. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49:257–266Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Spence JE, Corey LA, Nance WE, Marazita ML, Kendler KS, Schieken RM: Molecular analysis of twin zygosity using VNTR DNA probes (abstract). Am J Hum Genet 1988; 43:A159Google Scholar

18. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID). New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1985Google Scholar

19. Neale MC, Eaves LJ, Kendler KS: The power of the classical twin study to resolve variation in threshold traits. Behav Genet 1994; 24:239–258Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Hettema JM, Prescott CA, Kendler KS: A population-based twin study of generalized anxiety disorder in men and women. J Nerv Ment Dis 2001; 189:413–420Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Neale MC, Cardon LR: Methodology for Genetic Studies of Twins and Families. Dordrecht, the Netherlands, Kluwer Academic, 1992Google Scholar

22. Neale MC, Boker SM, Xie G, Maes HH: Mx: Statistical Modeling, 5th ed. Richmond, Medical College of Virginia of Virginia Commonwealth University, Department of Psychiatry, 1999Google Scholar

23. Akaike H: Factor analysis and AIC. Psychometrika 1987; 52:317–332Crossref, Google Scholar

24. Fanous A, Gardner CO, Prescott CA, Cancro R, Kendler KS: Neuroticism, major depression and gender: a population-based twin study. Psychol Med 2002; 32:719–728Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Kendler KS, Neale MC, Kessler RC, Heath AC, Eaves LJ: Major depression and generalized anxiety disorder: same genes, (partly) different environments? Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49:716–722Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Kirk KM, Birley AJ, Statham DJ, Haddon B, Lake RI, Andrews JG, Martin NG: Anxiety and depression in twin and sib pairs extremely discordant and concordant for neuroticism: prodromus to a linkage study. Twin Res 2000; 3:299–309Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Lesch KP, Bengel D, Heils A, Sabol SZ, Greenberg BD, Petri S, Benjamin J, Muller CR, Hamer DH, Murphy DL: Association of anxiety-related traits with a polymorphism in the serotonin transporter gene regulatory region. Science 1996; 274:1527–1531Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Fullerton J, Cubin M, Tiwari H, Wang C, Bomhra A, Davidson S, Miller S, Fairburn C, Goodwin G, Neale MC, Fiddy S, Mott R, Allison DB, Flint J: Linkage analysis of extremely discordant and concordant sibling pairs identifies quantitative-trait loci that influence variation in the human personality trait neuroticism. Am J Hum Genet 2003; 72:879–890Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Loehlin JC: Genes and Environment in Personality Development. Newbury Park, Calif, Sage Publications, 1992Google Scholar

30. Foley DL, Neale MC, Kendler KS: Reliability of a lifetime history of major depression: implications for heritability and comorbidity. Psychol Med 1998; 28:857–870Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar