Panic Attack as a Risk Factor for Severe Psychopathology

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The purpose of the study was to examine the relationship between panic attack and the onset of specific mental disorders and severe psychopathology across the diagnostic spectrum among adolescents and young adults. METHOD: Data were drawn from the Early Developmental Stages of Psychopathology Study (N=3,021), a 5-year prospective longitudinal study of psychopathology among youths ages 14–24 years at baseline in the community. Multiple logistic regression analyses were used to examine the associations between panic attacks at baseline, comorbid mental disorders in adolescence, and the risk of mental disorders across the diagnostic spectrum at follow-up. RESULTS: The large majority of subjects with panic attacks at baseline developed at least one DSM-IV mental disorder at baseline (89.4% versus 52.8% of subjects without panic attacks). Subjects with panic attacks at baseline had significantly higher baseline levels of any anxiety disorder (54.6% versus 25.0%), any mood disorder (42.7% versus 15.5%), and any substance use disorder (60.4% versus 27.5%), compared to subjects without panic attacks at baseline. Preexisting panic attacks significantly increased the risk of onset of any anxiety disorder, social phobia, specific phobia, generalized anxiety disorder, any substance use disorder, and any alcohol use disorder at follow-up in young adulthood, and these associations persisted after adjustment for all comorbid mental disorders assessed at baseline. More than one-third (37.6% versus 9.8%) of the subjects with panic attack at baseline met the criteria for at least three mental disorders at follow-up during young adulthood. CONCLUSIONS: Panic attacks are associated with significantly increased odds of mental disorders across the diagnostic spectrum among young persons and appear to be a risk factor for the onset of specific anxiety and substance use disorders. Investigation of key family, environmental, and individual factors associated with the onset of panic attacks, especially in youth, may be an important direction for future research.

The prognostic significance of panic attacks has been a topic of renewed interest in recent years. Research efforts to examine the predictive strength of panic attacks with regard to psychopathology have included numerous studies that have documented associations between panic attacks and higher than expected rates of comorbid mental disorders (1–21). This evidence comes mainly from two sources. First, data from clinical samples have shown consistent links between panic attacks and the range of mental disorders (17–21). Second, epidemiologic studies have shown that panic attacks are common and highly comorbid among adults with depressive (9, 10, 14–16), bipolar (2, 14), anxiety (7, 8, 11, 12, 14), substance use (6), and psychotic disorders(4, 5).

Although evidence cumulatively suggests a link between panic attacks and the range of mental disorders, there are several methodological features of previous research that limit the generalizability of these findings. First, previous studies have included adults, therefore these findings may not apply to adolescents or young adults. Second, studies to date have used cross-sectional designs. Third, previous studies from both clinical and epidemiologic samples have suggested that panic attacks are associated with a range of mental disorders, yet prior investigations have not measured the relationship between panic attacks and the severity of psychopathology in the community.

The goal of the current study was to address these questions by examining: 1) the relation between panic attack and mental disorders across the diagnostic spectrum among young persons and 2) the association between panic attack during adolescence and the risk of specific mental disorders and severity of psychopathology at follow-up during young adulthood by using prospective assessment of panic attacks and mental disorders within an epidemiologic study design. On the basis of previous findings among adults in the community (5–8), it was hypothesized that a history of panic attack would be associated with higher risk of mental disorders across the diagnostic spectrum. We also predicted that panic attack would be associated with severe psychopathology, reflected by multimorbidity, compared to a lack of panic attacks, among young adults in the community, based on previous evidence of the extensive comorbidity and psychosocial morbidity associated with panic attacks among adults (12–22).

Method

Sample

Data were collected as part of the Early Developmental Stages of Psychopathology Study, a prospective, longitudinal study designed to collect data on the prevalence, risk factors, comorbidity, and course of mental and substance use disorders in a representative community sample, which consisted of 3,021 subjects ages 14–24 years at baseline in Munich, Germany. The study consists of a baseline (time 0) survey, two follow-up surveys (time 1 and time 2), and a family history component (data not included in this report).

The baseline sample was drawn in 1994 from government registries in metropolitan Munich, Germany, of registrants expected to be ages 14–24 years at the time of the baseline interview in 1995. Because the study was designed as a longitudinal panel with specific emphasis on early developmental stages of psychopathology, 14–15-year-olds were sampled at twice the probability of people ages 16–21 years, and 22–24-year-olds were sampled at half this probability. At baseline, a total of 3,021 interviews were completed, resulting in a response rate of 71%. Two follow-up assessments were completed after the initial baseline investigation, covering an overall period of 3–4 years. The first follow-up survey was conducted only with subjects ages 14–17 years at baseline, whereas the second follow-up survey was conducted with all subjects. At the first follow-up survey 14–25 months after baseline (mean interval=20 months, SD=3), a total of 1,228 interviews were completed, resulting in a response rate of 88%. From the 3,021 subjects of the baseline survey, a total of 2,548 interviews were completed at the second follow-up survey 34–50 months after baseline (mean interval=42 months, SD=2), resulting in a response rate of 84%. A more detailed description of the study is presented elsewhere (23, 24).

Diagnostic Assessment

The survey staff throughout the entire study period (including the family history component of the study) consisted of 57 clinical interviewers, most of whom were clinical psychologists with extensive experience in diagnostic interviewing, including experience with the Munich Composite International Diagnostic Interview (25). At baseline, 25 professional health research interviewers recruited from a survey company were also involved. Formal training with the Munich Composite International Diagnostic Interview took place for 2 weeks, followed by at least 10 closely monitored practice interviews and additional 1-day booster sessions throughout the study. (See references 23 and 24 for more specific information on the assessment procedure.)

Diagnostic findings reported in this article were obtained by using the Munich Composite International Diagnostic Interview/DSM-IV diagnostic algorithms, which allow for the assessment of symptoms, syndromes, and diagnoses of 48 mental disorders. Test-retest reliability and validity for the full Munich Composite International Diagnostic Interview have been reported elsewhere, along with descriptions of the interview format and coding conventions (26–28). Panic attacks were defined by using DSM-IV criteria. Data for subjects with panic attacks and for those with panic disorder were collapsed, as previous data have failed to show an empirical basis for this distinction (29).

Statistical Analyses

Data were weighted to consider different sampling probabilities as well as systematic nonresponse at baseline according to age, gender, and geographic distribution (24). The Stata Software package (30) was used to compute robust confidence intervals (CIs) by applying the Huber-White sandwich matrix (31), which is required when basing analyses on weighted sample sizes. Lifetime prevalence at baseline denotes the rate of the disorder under consideration in the total sample or subsample and covers the respondents’ lifetime period before the baseline assessment. Incidence was defined as new outcomes during the follow-up period (time 0 to time 2) among subjects who were nonaffected at baseline. Cumulative lifetime incidence was calculated by adding the numbers of baseline, time 1, and time 2 incident cases. Logistic regressions with odds ratios were used to describe associations with baseline, incident onset, and cumulative lifetime incidence of mental disorders, with adjustment for the confounders age and sex. In further analyses, the relationship between panic attack at baseline and the risk of each incident mental disorder was also adjusted for differences in all comorbid disorders at baseline. We also examined the severity of psychopathology at each time point, using the same method, to describe the association between panic attack status at baseline and the number of mental disorders at baseline, the number of mental disorders at incident follow-up, and the cumulative lifetime incidence of mental disorders. These analyses were rerun to examine the baseline, follow-up, and cumulative lifetime incidence of anxiety disorders, mood disorders, and substance use disorders. Additional parallel sets of analyses were conducted to investigate the relationship of major depressive episode, specific phobia, and any eating disorder at baseline with the risk of subsequent psychopathology. These analyses were conducted to investigate the extent to which the relationship between panic attacks and risk of subsequent psychopathology is specific, compared to that associated with other common mental disorders.

Analytic Sample

Youths with panic attacks (or panic disorder) at baseline (weighted N=131) were included in the analysis of comorbid disorders at baseline and compared on the presence of each mental disorder and number of mental disorders at baseline and follow-up with youths without panic attacks at baseline (weighted N=2,890). For the analyses of the relationship between panic attacks and cumulative lifetime incidence of each mental disorder and between panic attacks and the number of mental disorders, subjects with panic attacks (or panic disorder) (weighted N=186) at any of the three waves (time 0, time 1, or time 2) were compared with those without panic attacks or panic disorder (lifetime) (weighted N=2,361). These groups were derived from the follow-up sample of 2,548 subjects.

Results

Baseline Prevalence of Mental Disorders

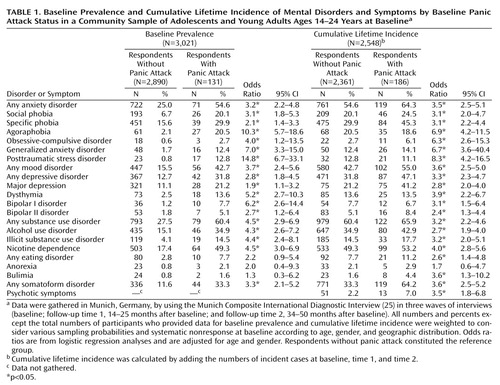

Panic attacks at baseline were associated with a higher likelihood of any disorder at baseline (89.4% versus 52.8%) (odds ratio=8.5, CI=4.0–17.8) and with a higher likelihood of each mental disorder assessed at baseline, compared to a lack of panic attacks, although the associations with any eating disorder, anorexia, or bulimia failed to reach statistical significance (Table 1). The strongest associations at baseline were between panic attacks and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (12.8% versus 0.8%) (odds ratio=14.8, CI=6.7–33.1), agoraphobia (20.5% versus 2.1%) (odds ratio=10.3, CI=5.7–18.6), generalized anxiety disorder (12.4% versus 1.7%) (odds ratio=7.0, CI=3.3–15.0), obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) (2.7% versus 1.7%) (odds ratio=4.0, CI=1.2–13.5), and bipolar I disorder (7.7% versus 1.2%) (odds ratio=6.2, CI=2.6–14.4). These associations were adjusted for age and gender.

The presence of panic attacks at any of the three waves (time 0, time 1, or time 2) was associated with a significantly increased cumulative lifetime incidence of any anxiety disorder, any mood disorder, any substance use disorder, any eating disorder, and any somatoform disorder/syndrome (Table 1). Patterns in the strength of associations between panic attacks and specific anxiety, mood, and substance use disorders were similar to those observed among baseline comparisons. An association between panic attacks and a significantly higher cumulative lifetime incidence of psychotic symptoms was also evident (7.0% versus 2.2%) (odds ratio=3.5, CI=1.8–6.8).

Baseline Associations

Among young persons with panic attacks at baseline, 13.6% were free of panic attacks and mental disorders at follow-up (versus 43.2% among subjects without panic attack at baseline) (p<0.0001, odds ratio=4.9, CI=2.6–9.4). Among those with panic attacks at baseline, the odds of having two or more comorbid mental disorders at follow-up (16.5% [N=21] versus 14.5% [N=419]) (odds ratio=5.8, CI=2.6–12.7) were about six times higher, the odds of having three or more mental disorders at follow-up were approximately 20 times higher (37.6% [N=49] versus 9.8% [N=282]) (odds ratio=19.4, CI=9.3–40.5), and the odds of having four or more mental disorders at follow-up were nearly 40 times higher (19.0% [N=25] versus 2.3% [N=66]) (odds ratio=39.9, CI=17.3–92.1), compared with the odds among those who did not have panic attacks at baseline.

Incidence of Mental Disorders at Follow-Up

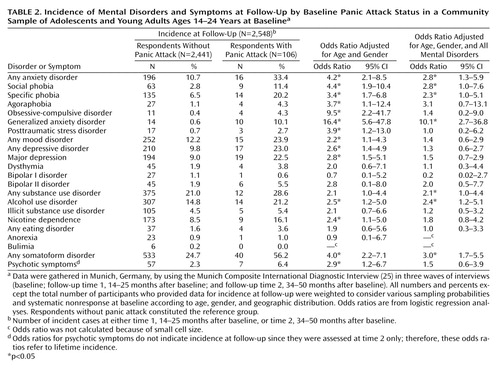

Even after adjustment for all comorbid disorders at baseline, panic attacks at baseline were associated with a higher risk for first onset of any anxiety disorder (odds ratio=2.8, CI=1.3–5.9), social phobia (odds ratio=2.8, CI=1.0–7.6), specific phobia (odds ratio=2.3, CI=1.0–5.1), generalized anxiety disorder (odds ratio=10.1, CI=2.7–36.8), any substance use disorder (odds ratio=2.1, CI=1.0–4.4), any alcohol use disorder (odds ratio=2.4, CI=1.2–5.1), and any somatoform disorder (odds ratio=3.0, CI=1.7–5.5) at follow-up at either time 1 or time 2 (Table 2).

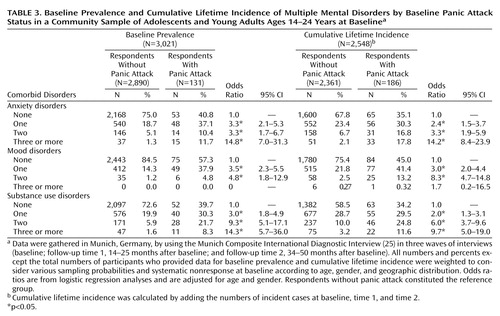

Having panic attacks at baseline was associated with significantly increased odds of having multiple anxiety, mood, and substance use disorders at baseline, compared to lack of panic attacks at baseline (Table 3). It is interesting to note that among those with panic attacks the likelihood of having exactly one anxiety disorder at baseline (37.1%) was very similar to that of having exactly one mood disorder (37.9%) or exactly one substance use disorder (30.3%). Further, the odds of having two versus no substance use disorders (odds ratio=9.3, CI=5.1–17.1) and two versus no mood disorders (odds ratio=4.8, CI=1.8–12.9) exceeded those associated with having two anxiety disorders (odds ratio=3.3, CI=1.7–6.7), while the odds of having at least three substance use disorders (odds ratio=14.3, CI=5.7–36.0) were relatively comparable to those of having three or more anxiety disorders (odds ratio=14.8, CI=7.0–31.3) among those with panic attacks, compared to those without panic attacks.

Similar to the baseline associations, panic attacks at any of the three time points were associated with a significantly higher cumulative lifetime incidence of multiple anxiety, mood, and substance use disorders (Table 3). For instance, panic attacks were associated with a significantly increased likelihood of two anxiety, mood, or substance use disorders and at least three anxiety or substance use disorders.

Incidence of Multiple Mental Disorders

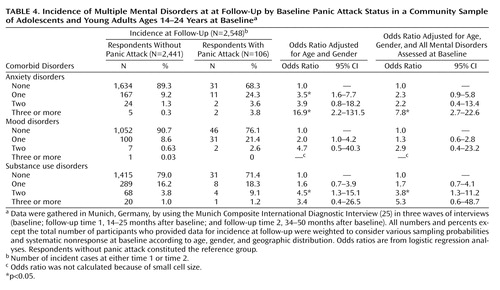

Panic attacks at baseline were associated with higher odds of having at least two incident anxiety disorders (odds ratio=3.9, CI=0.8–18.2), at least two incident mood disorders (odds ratio=4.7, CI=0.5–40.3), and two or more incident substance use disorders (odds ratio=4.5, CI=1.3–15.1) with relatively comparable strength, although only the relation with substance use disorders reached statistical significance (Table 4). Panic attacks at baseline were associated with higher odds of having three or more anxiety disorders (odds ratio=7.8, CI=2.7–22.6) and at least two substance use disorders (odds ratio=3.8, CI=1.3–11.2), after adjustment for all comorbid disorders at baseline (Table 4). The odds of multiple mental disorders among those with panic attacks, compared to those without, was consistently higher in each category, although most results failed to reach statistical significance.

Supplementary Analyses

In an attempt to determine whether the relationships between panic attack and subsequent risk of both comorbid mental disorder across the range of psychopathology and of severe psychopathology (i.e., multiple comorbid mental disorders) showed any specificity, we compared the relationships of major depressive episode, specific phobia, and any eating disorder with the subsequent risk of comorbid mental disorders. Although this crude exploration should not be regarded as an appropriate test, the results confirmed first that the presence of any diagnosis increased the likelihood of additional comorbid diagnoses. The associations, however, were not as strong, consistent, or applicable to the range of mental disorders as were the associations with panic attacks. Further, it should be noted that this analysis required the comparison of the effects of panic attacks with the effects of full-blown DSM-IV disorders, which lends support to the predictive strength of panic attacks.

Discussion

These data are consistent with and extend prior research with adults by showing that panic attacks are associated with high levels of comorbidity and multimorbidity across the diagnostic spectrum among adolescents and young adults in the community. Further, these results suggest that beyond the associations with panic disorder and agoraphobia, panic attacks are associated with increased risk of the onset of anxiety disorders (specifically generalized anxiety disorder, social phobia, and specific phobia), affective disorders, and substance use disorders, especially alcohol use disorders, by young adulthood. The findings also indicate that the majority of respondents who report panic attacks have at least one comorbid mental disorder during adolescence and that by young adulthood, more than one-half of those with panic attacks have multiple mental disorders, which is a significantly higher percentage than was found among their peers without panic attacks.

These data provide initial evidence suggesting that the high rates of comorbid mental disorders among adults with panic attacks are already evident among younger persons with panic attacks. The data suggest that while panic attacks in themselves are not considered a disorder or a condition that requires treatment (DSM-IV), more than one-half of those with panic attacks have at least one full-blown anxiety, mood, or substance use disorder, which may be relevant from both a clinical and public health perspective.

The type of associations as well as the strength of associations between panic attacks and comorbid mental disorders and multiple morbidity appeared fairly unique to panic attacks, despite the fact that there is a consistent association between having one mental disorder and a higher risk of comorbidity for all mental disorders. The results of our additional analyses for other mental disorders (e.g., major depression, eating disorders, specific phobia) also demonstrated higher rates of comorbidity; however, these associations were not consistent across the range of mental disorders nor were they associated with multiple mental disorders, in contrast to the consistent associations between panic attacks and the range of mental disorders. Therefore, the results appear consistent with previous data in finding a higher risk of comorbidity but provide new information regarding the strength, persistence, and comprehensiveness of panic attack as a factor associated with greater risk of the range of mental disorders.

Our second set of analyses revealed that panic attacks are independently associated with a higher risk of the onset of anxiety and substance use disorders among young persons. The associations between panic attacks and the risk of phobias (i.e., specific phobia, social phobia) and generalized anxiety disorder remained statistically significant, albeit in an attenuated fashion after adjustment for comorbidity. In contrast, the observed relationship between panic attacks and the risk of OCD, PTSD, and major depression were no longer evident after adjustment. One possible explanation is that this clustering of disorders reflects a distinction in the nature of the underlying etiologic mechanisms between panic attacks and the onset of each mental disorder by young adulthood. For instance, it may be that there are genetic links between panic attacks and alcohol use disorders, a hypothesis that is consistent with family study results (32, 33), while the relationship between panic attacks and PTSD may be mediated by comorbid mental disorders or stressful life events, rather than through a direct link. We found that a significantly greater percentage (22.5%) of those with panic attacks developed major depression by early adulthood, compared with those without panic attacks (9.0%), and this finding is consistent with results from cross-sectional studies among adults (9, 10, 16). Yet, when we adjusted this association for the presence of comorbid disorders at baseline, it was not statistically significant. It may be that the younger age of this sample did not allow for enough time in the period of highest risk for onset of depression for this link to become observable, leading to small cell size. It could also be that the link is entirely due to comorbidity, although studies in adults have found a significant association, even after adjustment for the range of psychopathology (6, 9, 14, 15). It is also conceivable that the relationship between panic attacks and risk of depression is more strongly related to age or differentially related to age, compared with the associations between panic attacks and anxiety and substance use disorders, in light of the contrast between our findings and those from adult samples. In an attempt to determine whether there was one specific comorbid disorder that accounted for this decrease in the strength of each link (i.e., whether the relationship between panic attacks and major depression was not due solely to comorbidity with alcohol dependence but was the result of a small contribution to the relationship made by each comorbid disorder), we fitted additional logistic regressions and included each comorbid disorder in a separate model. The results of these analyses suggested that each comorbid disorder made a small contribution to this link and that no one specific disorder could be identified as accounting for these patterns. This result was consistent across disorders.

Future studies that use longitudinal data to investigate more closely the mechanisms of these relationships may lead to a more in-depth understanding of the possible etiologic links underlying each of these associations. It is interesting to note that the observed relationship between panic attacks and psychotic symptoms is consistent with and contributes to growing evidence from clinical and epidemiologic studies of an association between panic and various forms of psychosis (4, 5, 34). Unfortunately, psychosis was not evaluated at the baseline assessment of the Early Developmental Stages of Psychopathology Study, so calculation of risk of psychosis associated with panic attacks was not possible.

The limitations of this study should be noted. Small cell size because of low prevalence of less common disorders may have limited our ability to detect significant effects (e.g., for bipolar disorder). Our findings were obtained in a sample of 14–24-year-olds living in Munich, a metropolitan area with a population that has a relatively high quality of life and high socioeconomic status. Thus, direct comparisons with other age groups and areas characterized by other sociodemographics must be made with caution. That the period of high risk for onset of mental disorders had not fully passed at the time of the final assessment suggests that these estimates may underestimate lifetime risks.

Despite these limitations, the current study confirms previous findings of linkages between panic attacks and the range of mental disorders seen cross-sectionally among adults (9, 12–15, 20) and extends these associations to adolescents and young adults. Use of prospective methods to examine the relationship between panic attacks and the onset of the range of mental disorders in young adulthood in this study provides preliminary evidence of links between panic attacks and greater risk of onset of anxiety and substance use disorders during young adulthood. Finally, these data suggest that panic attacks are associated with severe psychopathology (defined as the presence of multiple mental disorders), with a majority of young persons with panic attacks meeting diagnostic criteria for at least three comorbid mental disorders by young adulthood. Future studies that replicate and examine each association observed in this study in greater depth across time will be useful in untangling the observed links and in exploring the potential utility of preventive interventions among those at risk. Investigation of the predictors for panic attacks, including family, genetic, social, and environmental risk factors, is needed.

|

|

|

|

Received Aug. 8, 2002; revision received June 3, 2003; accepted Dec. 22, 2003. From the Department of Clinical Psychology and Epidemiology, Max Planck Institute of Psychiatry; the Department of Epidemiology, Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University, New York; and the Department of Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, Technical University of Dresden, Dresden, Germany. Address reprint requests to Dr. Lieb, Max Planck Institute of Psychiatry, Kraepelinstr. 2, 80804 Munich, Germany; [email protected] (e-mail). This work is part of the Early Developmental States of Psychopathology Study and is funded by the German Ministry of Research and Technology, project nos. 01 EB 9405/6 and 01 EB 9901/6. Principal investigators are Dr. Hans-Ulrich Wittchen and Dr. Roselind Lieb. Current or former staff members of the Early Developmental Stages of Psychopathology group are Dr. Kirsten von Sydow, Dr. Gabriele Lachner, Dr. Axel Perkonigg, Dr. Peter Schuster, Dr. Franz Gander, Michael Hofler, Dipl.-Stat., Holger Sonntag, Dipl.-Psych., Esther Beloch, Mag. Phil., Martina Fuetsch, Mag. rer. nat., Elzbieta Garcznski, Dipl.-Psych., Alexandra Holly, Dipl.-Psych., Antonia Vossen, Dipl.-Psych., Dr. Ursula Wunderlich, and Petra Zimmermann, Dipl.-Psych. Scientific advisors are Dr. Jules Angst (Zurich, Switzerland), Dr. Jurgen Margraf (Basel, Switzerland), Dr. Gunther Esser (Potsdam, Germany), Dr. Kathleen Merikangas (Yale University, New Haven, Conn.), and Dr. Ron Kessler (Harvard University, Boston).

1. Weissman MM, Wickramaratne P, Adams PB, Lish JD, Horwath E, Charney D, Woods SW, Leeman E, Frosch E: The relationship between panic disorder and major depression: a new family study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993; 50:767–780Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Chen Y-W, Dilsaver SC: Comorbidity of panic disorder in bipolar illness: evidence from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area survey. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:280–282Link, Google Scholar

3. Olfson M, Broadhead WE, Weissman MM, Leon AC, Farber L, Hoven CW, Kathol R: Subthreshold psychiatric symptoms in a primary care group practice. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996; 53:880–886Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Cosoff SJ, Hafner RJ: The prevalence of comorbid anxiety in schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder and bipolar disorder. Aust NZ J Psychiatry 1998; 32:67–72Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Bermanzohn PC, Arlow PB, Albert C, Siris SG: Relationship of panic attacks to paranoia (letter). Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:1469Abstract, Google Scholar

6. Regier DA, Rae DS, Narrow WE, Kaelber CT, Schatzberg AF: Prevalence of anxiety disorders and their comorbidity with mood and addictive disorders. Br J Psychiatry Suppl 1998; 34:24–28Medline, Google Scholar

7. Pine DS, Gurley D, Brook J, Ma Y: The risk for early-adulthood anxiety and depression disorders in adolescents with anxiety and depressive disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998; 55:56–64Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Eaton WW, Badawi M, Melton B: Prodromes and precursors: epidemiologic data for primary prevention of disorders with slow onset. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:967–972Link, Google Scholar

9. Kessler RC, Stang PE, Wittchen HU, Ustun TB, Roy-Byrne PP, Walters EE: Lifetime panic-depression comorbidity in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998; 55:801–808Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Andrade L, Eaton WW, Chilcoat HD: Lifetime comorbidity of panic attacks and major depression in a population-based study: age of onset. Psychol Med 1996; 26:991–996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Eaton WW, Anthony JC, Romanoski A, Tien A, Gallo J, Cai G, Neufeld K, Schlaepfer T, Laugharne J, Chen LS: Onset and recovery from panic disorder in the Baltimore Epidemiologic Catchment Area follow-up. Br J Psychiatry 1998; 173:501–507Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Klerman GL, Weissman MM, Ouellette R, Johnson J, Greenwald S: Panic attacks in the community JAMA 1991; 265:742–746Google Scholar

13. Katerndahl DA, Realini JP: Comorbid psychiatric disorders in subjects with panic attacks. J Nerv Ment Dis 1997; 18:669–674Crossref, Google Scholar

14. Goodwin RD, Hamilton SP: Panic attack as a marker of core psychopathological processes. Psychopathology 2001; 34:278–288Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Roy-Byrne PP, Stang P, Wittchen HU, Ustun B, Walters EE, Kessler RC: Lifetime panic-depression comorbidity in the National Comorbidity Survey: association with symptoms, impairment, course and help-seeking. Br J Psychiatry 2000; 176:229–235Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Reed V, Wittchen H-U: DSM-IV panic attacks and panic disorder in a community sample of adolescents and young adults: how specific are panic attacks? J Psychiatr Res 1998; 32:335–345Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Kushner MG, Abrams K, Thuras P, Thuras P, Hanson KL: Individual differences predictive of drinking to manage anxiety among non-problem drinkers with panic disorder. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2000; 24:448–458Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Starcevic V, Uhlenduth EH, Kellner R, Pathak D: Comorbidity in panic disorder, II: chronology of appearance and pathogenic comorbidity. Psychiatry Res 1993; 46:285–293Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Craig T, Hwang MY, Bromet EJ: Obsessive-compulsive and panic symptoms in patients with first-admission psychosis. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159:592–598Link, Google Scholar

20. Battaglia M, Bertella S, Politi E, Bernardeschi L, Perna G, Gabriele A, Bellodi L: Age at onset of panic disorder: influence of familial liability to the disease and of childhood separation anxiety disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:1362–1364Link, Google Scholar

21. Goldstein RB, Wickramartne PJ, Horwath E, Weissman MM: Familial aggregation and phenomenology of early-onset (at or before age 20) panic disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1997; 54:271–278Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Weissman MM, Klerman GL, Markowitz JS, Ouellette R: Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in panic disorder and attacks. N Engl J Med 1989; 321:1209–1214Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Wittchen H-U, Perkonigg A, Lachner G, Nelson CB: Early developmental stages of psychopathology study (EDSP): objectives and design. Eur Addict Res 1998; 4:18–27Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Lieb R, Isensee B, von Sydow K, Wittchen H-U: The Early Developmental Stages of Psychopathology Study (EDSP): a methodological update. Eur Addict Res 2000; 6:170–182Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Wittchen H-U, Pfister H (eds): DIA-X-Interviews: Manual für Screening-Verfahren und Interview; Interviewheft Längsschnittuntersuchung (DIA-X-Lifetime); Ergänzungsheft (DIA-X-Lifetime); Interviewheft Querschnittuntersuchung (DIA-X-12 Monate); Ergänzungsheft (DIA-X-12 Monate); PC-Programm zur Durchführung des Interviews (Längs- und Querschnittuntersuchung); Auswertungsprogramm. Frankfurt, Swets & Zeitlinger, 1997Google Scholar

26. Reed V, Gander F, Pfister H, Steiger A, Sonntag H, Trenkwalder C, Hundt W, Wittchen H-U: To what degree does the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) correctly identify DSM-IV disorders? testing validity issues in a clinical sample. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 1998; 7:142–155Crossref, Google Scholar

27. Wittchen H-U, Lachner G, Wunderlich U, Pfister H: Test-retest reliability of the computerized DSM-IV version of the Munich-Composite International Diagnostic Interview (M-CIDI). Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1998; 33:568–578Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Lachner G, Wittchen H-U, Perkonigg A., Holly A, Schuster P, Wunderlich U, Türk D, Garczynski E, Pfister H: Structure, content and reliability of the Munich-Composite International Diagnostic Interview (M-CIDI) substance use sections. Euro Addict Res 1998; 4:28–41Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Leon AC, Klerman GL, Weissman MM, Fyer AJ, Johnson J: Evaluating the diagnostic criteria for panic disorder: measures of social morbidity as criteria. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1992; 27:180–184Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Stata Statistical Software, Release 6.0. College Station, Tex, Stata Corp, 1999Google Scholar

31. Royall RM: Modeling robust confidence intervals using maximum likelihood estimators. Int Stat Rev 1986; 54:221–226Crossref, Google Scholar

32. Merikangas KR, Stevens DE, Fenton B, Stolar M, O’Malley S, Woods SW, Risch N: Comorbidity and familial transmission of alcohol and anxiety disorders. Psychol Med 1998; 28:773–788Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Merikangas KR, Risch NJ, Weissman MM: Comorbidity and co-transmission of alcoholism, anxiety and depression. Psychol Med 1994; 24:69–80Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Bermanzohn PC, Porto L, Arlow PB, Pollack S, Stronger R, Siris SG: Hierarchical diagnosis in chronic schizophrenia: a clinical study of co-occurring syndromes. Schizophr Bull 2000; 26:517–525Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar