Changes in Glucose and Cholesterol Levels in Patients With Schizophrenia Treated With Typical or Atypical Antipsychotics

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The association of hyperglycemia and hypercholesterolemia with use of atypical antipsychotics has been documented in case reports and uncontrolled studies. The authors’ goal was to assess the effects of clozapine, olanzapine, risperidone, and haloperidol on glucose and cholesterol levels in hospitalized patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder during a randomized double-blind 14-week trial. METHOD: One hundred fifty-seven patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder who were inpatients at four hospitals were originally included in the study. The 14-week trial consisted of an 8-week fixed-dose period and a 6-week variable-dose period. Planned assessments included fasting glucose and cholesterol, which were collected at baseline and at the end of the 8-week period and the following 6-week period. RESULTS: One hundred eight of the 157 patients provided blood samples at baseline and at least at one point after random assignment to clozapine, olanzapine, risperidone, or haloperidol during the treatment trial. Seven of these patients had diabetes; their glucose levels were >125 mg/dl at baseline. Data from 101 patients were used for statistical analyses. During the initial 8-week period there was an overall significant increase in mean glucose levels. There were significant increases in glucose levels at the end of the 8-week fixed-dose period for patients given clozapine (N=27) and those given haloperidol (N=25). The olanzapine group showed a significant increase of glucose levels at the end of the 6-week variable-dose period (N=22). Fourteen of the 101 patients developed abnormal glucose levels (>125 mg/dl) during the trial (six with clozapine, four with olanzapine, three with risperidone, and one with haloperidol). Cholesterol levels were increased at the end of the 8-week fixed-dose period for the patients given clozapine (N=27) and those given olanzapine (N=26); cholesterol levels were also increased at the end of the 6-week variable-dose period for patients given olanzapine (N=22). CONCLUSIONS: In this prospective randomized trial, clozapine, olanzapine, and haloperidol were associated with an increase of plasma glucose level, and clozapine and olanzapine were associated with an increase in cholesterol levels. The mean changes in glucose and cholesterol levels remained within clinically normal ranges, but approximately 14% of the patients developed abnormally high glucose levels during the course of their participation in the study.

Abnormalities in glucose regulation have been reported in schizophrenia before and after the introduction of antipsychotic medications (1–6). Hyperglycemia in the context of treatment with atypical antipsychotic medications has been documented in several series of uncontrolled case reports, and clozapine and olanzapine have been implicated more frequently than risperidone (7–35). Complicating this issue is the observation that patients with schizophrenia are more likely to develop diabetes mellitus than the general population (4), regardless of antipsychotic use. In addition, there is a trend toward an increase in the prevalence of diabetes mellitus in the general population (36). Large epidemiological studies have provided conflicting information regarding the relative risk of diabetes and exposure to different antipsychotics (33, 37–40). Significant elevations in triglyceride and cholesterol levels have also been reported in association with atypical antipsychotic treatment (26, 32, 41). However, the true incidence of both hyperglycemia and hypercholesterolemia induced by different typical or atypical medications is not known at this time. We had the opportunity to study the effects of both typical and atypical antipsychotic medications on glucose and cholesterol levels during a randomized, controlled, prospective trial in patients with suboptimal response to previous antipsychotic medication.

Method

The data for this investigation were collected during a randomized, double-blind, 14-week clinical trial of clozapine, olanzapine, risperidone, and haloperidol in patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. The primary purpose of the trial was to investigate the comparative efficacy of atypical antipsychotics in a group of inpatients with suboptimal therapeutic response to previous antipsychotic treatments. A brief description of the parent study is provided here; the complete report is available elsewhere (42).

Study Design

The prospective, double-blind trial consisted of two periods: an 8-week, fixed-dose period (period 1) and a 6-week, variable-dose period (period 2). The fixed-dose target levels were 500 mg/day for clozapine, 20 mg/day for olanzapine, 8 mg/day for risperidone, and 20 mg/day for haloperidol. The actual mean dose levels for the 101 patients who were included in the statistical analyses for the current study were 443.7 mg/day (SD=120.2) for clozapine, 20.1 mg/day (SD=1.2) for olanzapine, 8.5 mg/day (SD=2.2) for risperidone, and 20.0 mg/day (SD=0.0) for haloperidol at the end of period 1. At the end of period 2 the mean dose levels were 477.2 mg/day (SD=157.2), 31.4 mg/day (SD=6.0), 11.6 mg/day (SD=3.7), and 25.8 mg/day (SD=5.1) for clozapine, olanzapine, risperidone, and haloperidol, respectively.

Benztropine, 4 mg/day, was administered prophylactically to all patients receiving haloperidol. Patients assigned to atypical antipsychotics were initially receiving only benztropine placebo, but if the patient’s psychiatrist determined clinically that the patient should be treated for extrapyramidal side effects, prescriptions for “benztropine supplements” could be written, resulting in real benztropine gradually replacing benztropine placebo (up to 6 mg/day). Propranolol was allowed for the treatment of akathisia. Lorazepam, diphenhydramine hydrochloride, and chloral hydrate were permitted as needed for agitation and insomnia. No other adjunctive psychotropic medication was allowed in the study.

Subjects

The subjects were inpatients at four hospitals, two in New York State and two in North Carolina. Patients met DSM-IV criteria for schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder and remained hospitalized throughout the trial. All patients met the following criteria for suboptimal treatment response: 1) presence of persistent positive symptoms (hallucinations, delusions, or marked thought disorder) after at least 6 contiguous weeks of treatment with one or more typical antipsychotics at doses equivalent to or greater than 600 mg/day of chlorpromazine, 2) a poor level of functioning over the past 2 years, and 3) a total score greater than 60 on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (43). Patients were excluded from the trial if they had 1) a history of failure to respond to clozapine, risperidone, or olanzapine; 2) a history of clozapine, olanzapine, risperidone, or haloperidol intolerance; 3) depot antipsychotic treatment within 30 days before random assignment to one of the four drugs; or 4) substantial medical illness. After complete description of the study, written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Assessments

Assessments for the present analyses included fasting blood samples for glucose and cholesterol at baseline (before the first dose of study medication) and at the end of periods 1 and 2. Patients were included in the study if their glucose levels at baseline and at least one other time point during the study were available. Only results of blood samples collected at morning fasting times were included in the analyses. Plasma glucose and cholesterol levels were determined by enzymatic procedures applying the Boehringer Mannheim/Hitachi 714 automated chemistry analyzer and using the standard analytical system packs Glucose/HK and Cholesterol/HP. Patients’ weight was determined at baseline and endpoint of each period. Patients’ height was measured at the time of enrollment in the study. Weight gain was computed as the absolute and relative (%) change in body weight (kg) between baseline and study endpoint. Body mass index was computed as body weight (kg) divided by the square of height (m2).

Statistical Analysis

The principal objective of the analyses described in this report was to examine change in glucose and cholesterol levels during treatment with typical and atypical antipsychotics and to determine the incidence of hyperglycemia during such treatment in patients who had no known history of diabetes at the time of enrollment in the study. Accordingly, patients whose glucose blood levels at baseline were within normal laboratory limits constituted the main study group for the statistical analyses.

The relationship between change in glucose and cholesterol levels and antipsychotic medication was investigated by analysis of covariance (ANCOVA). Changes in glucose and cholesterol levels between baseline and the end of period 1 and between baseline and the end of period 2 were used as the dependent variables; a separate analysis was performed for each of the two measures in each of the two study periods. Last observation carried forward analysis was used within the respective study periods. Type of medication (treatment group) was used as the independent variable. Glucose and cholesterol levels at baseline were used as covariates. Post hoc analyses (Tukey’s Studentized range test for pairwise comparisons) for glucose and cholesterol levels were conducted between the medication groups. We conducted paired t tests to examine specific differences between baseline of period 1 and period 2 for each medication group for both glucose and cholesterol levels.

To investigate change over time in terms of transitions from normal to abnormal metabolic ranges, we constructed shift tables for each of the two study periods by using each of the two laboratory indexes (glucose and cholesterol). An abnormal glucose level was defined in our study as >125 mg/dl on the basis of one of the criteria of the American Diabetes Association (44); an abnormal cholesterol level was defined as greater than 200 mg/dl.

Since the main study group comprised patients whose baseline glucose blood levels were within normal range, the shift tables for glucose change (in each group) contained only two cells (normal to elevated, normal to normal) because each patient in the main group could exhibit one of two potential transition sequences between baseline and the end of a study period (i.e., normal to elevated or normal to normal). We used chi-square analysis to compare the proportion of patients who shifted from normal to abnormal glucose levels within each treatment group.

For cholesterol changes, the shift tables for each study group comprised four cells because elevated cholesterol values could occur in the main study group at baseline. Specifically, each of the four cells in a two-by-two shift table represented one of four potential transition sequences for each patient: normal to elevated, elevated to normal, normal to normal, elevated to elevated. Since the observations in a two-by-two shift table are not independent of each other, the analysis of the shift tables was based on McNemar’s test.

Relationship between weight gain and change in blood levels of glucose and cholesterol was investigated by ANCOVA. Weight gain was used as the dependent variable. Change in blood levels and medication group were used as independent variables; baseline weight and blood level at baseline were used as covariates. An interaction between blood level change and medication group was included in the model. Separate ANCOVAs were performed for glucose and cholesterol. We also conducted a correlation analysis between change in body weight and change in glucose level as well as change in cholesterol level for each medication group.

Results

Demographic and Basic Descriptive Data

Altogether, 157 patients entered the double-blind trial (42); 133 patients provided fasting glucose levels at some point during the study. Of these, seven were excluded for lack of baseline glucose level and 18 were excluded for lack of glucose levels at points during the study. This resulted in 108 patients who were included in the present report. Seven of these patients, diagnosed as having diabetes, had elevated glucose levels (>125 mg/dl) at baseline and were therefore not included in the main study group; their results are presented separately in this report. The remaining 101 patients constitute the main study group for statistical analyses.

Twenty-eight patients were randomly assigned to treatment with clozapine, 25 to haloperidol, 26 to olanzapine, and 22 to risperidone. The mean age of the study group was 40.33 years (SD=9.4). Eighty-five patients were men, and 16 were women. The clozapine group had a 25:3 male-to-female ratio, the haloperidol group 20:5, the olanzapine group 22:4, and the risperidone group 18:4 (p=0.81, n.s., two-sided Fisher’s exact test). Overall, patients were more likely to be diagnosed with schizophrenia (N=89) than with schizoaffective disorder. Twenty-nine (28.7%) of the patients were Caucasian, 59 (58.4%) were African American, 11 (10.9%) were Hispanic, and two (2.0%) were Asian-Pacific Islander.

Analysis of variance revealed a statistically significant difference among the four groups in baseline glucose levels (F=4.0, df=3, 100, p<0.01). Post hoc analyses (Tukey’s Studentized range test for pairwise comparisons) for glucose levels at baseline showed that patients in the clozapine and risperidone groups showed significantly (p<0.05) higher levels than those in the haloperidol group. No other group baseline difference relevant for the present analysis showed statistical significance in the analyses.

Patient Attrition

The completion rate for the full 14-week trial was 72.3% (N=73) among the 101 patients who were included in the main study group. There was no significant difference among the treatment groups in the proportion of patients completing the trial: 17 (60.7%) of 28 for clozapine, 20 (80.0%) of 25 for haloperidol, 22 (84.6%) of 26 for olanzapine, and 14 (63.6%) of 22 for risperidone.

Change in Glucose Levels Over Time

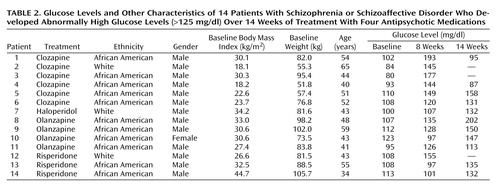

Descriptive information for change in glucose over time is displayed in Table 1. ANCOVA analyses indicated that differences among treatment groups reached significance in period 1 (F=4.4, df=3, 99, p=0.006) but not in period 2 (F=1.14, df=3, 72, n.s.). The increase in mean glucose blood levels over time reached statistical significance in the clozapine and haloperidol groups after 8 weeks. There was a statistically significant increase in the olanzapine group after 14 weeks (Table 1). No significant change in glucose was detected in the risperidone group. All increases in mean glucose levels remained within the normal clinical range. However, 14 (13.9%) of the 101 patients developed abnormal glucose levels (>125 mg/dl) at some point during randomized treatment (Table 2). African American patients were represented at a higher proportion (11 [18.6%] of 59) than white patients (three [10.3%] of 29) or Hispanic patients (none of 11) in the subgroup who displayed abnormal glucose. Differences among the three ethnic groups failed to reach statistical significance. The treatment group difference in the proportion of patients with a shift from normal to abnormally elevated glucose levels in periods 1 and 2 was not statistically significant, although there was a numerical trend for clozapine to show a higher number of shifts than the other three groups during period 1.

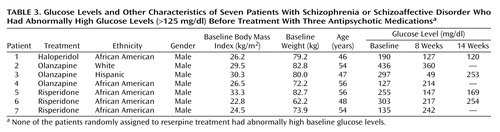

The seven patients who had elevated baseline glucose levels and who had diabetes mellitus were treated with antihyperglycemic agents during the study. The results for these patients were not included in the analysis of the main study group. As indicated by the data in Table 3, glucose levels decreased over the treatment period in five of these seven patients.

Change in Cholesterol Levels Over Time

Table 4 displays descriptive data for mean changes in cholesterol levels in period 1 and period 2. Differences among treatment groups reached significance in period 1 (F=10.4, df=3, 99, p<0.04) and marginal significance in period 2 (F=2.65, df=3, 72, p=0.06). Post hoc pairwise analyses (Tukey’s Studentized range tests) for period 1 revealed that the difference between the clozapine and haloperidol groups reached statistical significance (p<0.05). Analogous analyses for period 2 indicated no significant differences among the four treatment groups.

As shown in Table 4, there was an increase in cholesterol level in the clozapine and olanzapine groups in period 1. Cholesterol level elevation in the clozapine group in period 2 was of a similar magnitude to that seen in period 1, but it failed to reach statistical significance. The cholesterol increase in the olanzapine group reached statistical significance in period 2. No significant change over time in cholesterol was detected in the haloperidol and risperidone groups. All mean cholesterol increases remained within normal clinical range. The analysis of shift tables for cholesterol revealed no significant change over time in terms of transitions from normal to abnormal levels in any of the four treatment groups.

Relationship Between Weight Increase and Metabolic Changes

Weight gain in the parent study has been described elsewhere (45). In the current subgroup, the largest weight gain was seen with olanzapine (mean change=7.3 kg, SD=7.6) (paired t=4.94, df=27, p<0.0001), followed by clozapine (mean change=4.8 kg, SD=6.1) (paired t=4.1, df=26, p<0.0003) and risperidone (mean change=2.4 kg, SD=6.3) (paired t=1.79, df=21, p=0.09). There was minimal weight gain with haloperidol (mean change=0.9 kg, SD=5.7) (n.s.). ANCOVA indicated no main effect or treatment interaction for the relationship between glucose change and weight gain at endpoint.

A significant main effect for the association of cholesterol change and weight gain at endpoint was found for the four groups combined (F=12.01, df=1, 99, p=0.0008). Exploring the correlation between weight increase and cholesterol increase in each individual group, we found a significant association in the clozapine group (r=0.5, df=27, p=0.008) and in the olanzapine group (r=0.4, df=26, p=0.035). To investigate whether these associations were independent of baseline values, initial cholesterol levels and baseline weight were introduced as covariates in the analyses. Results indicated that the association in the clozapine group remained statistically significant (t=–2.37, df=1, 26, p<0.03), whereas the association in the olanzapine group obtained marginal significance (t=–1.93, df=1, 25, p=0.06). There was no association between baseline body mass index and increase in cholesterol level.

Discussion

We believe that this is the first report comparing the simultaneous effects of four antipsychotic medications on two important metabolic measures indexing glucose and lipid metabolism in patients with chronic schizophrenia who had a history of partial antipsychotic treatment response and who were randomly assigned to one of the four treatments under double-blind conditions. We found that clozapine and haloperidol were associated with significantly elevated mean glucose levels after 8 weeks of treatment, that olanzapine was associated with significantly elevated glucose levels after 14 weeks of treatment, and that risperidone was not associated with significant increases. The mean increases were modest and remained within clinically normal ranges, but approximately 14% of patients (six given clozapine, four given olanzapine, three given risperidone, and one given haloperidol) developed abnormally high glucose levels (>125 mg/dl) during the course of their study treatment. Clozapine showed a trend toward a higher number of patients shifting glucose levels from normal baseline levels to clinically abnormal levels after 14 weeks of treatment. Changes in glucose levels were independent of weight increase in all four treatment groups, despite significant weight gains, which were highest for olanzapine, followed by clozapine and risperidone Interestingly, in the small subset of patients with preexisting diabetes (N=7), antipsychotic treatment did not appear to have a deleterious effect on glucose metabolism.

In a nonrandomized study that compared the same three atypical and typical antipsychotics as our study, similar results were found for clozapine and olanzapine (46). When challenged with a modified glucose tolerance test, the olanzapine-treated and clozapine-treated groups had significant elevations in postload glucose levels at all time points compared with untreated control subjects and haloperidol-treated patients. In addition, mean glucose levels were significantly higher in the risperidone-treated group than in the control group.

We reviewed reports of hyperglycemia and diabetes mellitus during treatment with atypical antipsychotics since 1994 (7–35) and found that the majority of cases involved clozapine (N=20), followed by olanzapine (N=13). There are fewer case reports involving quetiapine (N=3), and the four case reports involving risperidone are recent. There is not enough information on the occurrence of diabetes mellitus with ziprasidone at this time. However, the frequency of case reports, which suffer from many limitations and reporting biases, is neither a true indication of incidence nor a measure of the relative risk of developing hyperglycemia. The rate found in the current study—14%—is about double the incidence rates of diabetes reported in a large survey of the U.S. population (6%–8%) (47) and somewhat higher than the current prevalence rate of 10% found by Dixon et al. (4) in an extensive study of three national U.S. schizophrenia samples.

Weight gain was not associated with hyperglycemia in our study. However, in a retrospective analysis of 573 patients receiving olanzapine for 39 weeks and more, Kinon et al. (48) found that the median nonfasting glucose at endpoint was marginally associated with weight change (p<0.10). This trend may relate to the longer drug exposure in the Kinon study.

Among the traditional neuroleptics, chlorpromazine (49) and thioridazine (50, 51) are the agents most closely associated with diabetes mellitus, although the associations are weaker than those with olanzapine or clozapine. In our study, the typical antipsychotic haloperidol was associated with an elevation of mean glucose levels within a clinically normal range. Haloperidol has been reported to increase insulin resistance and to be associated with higher fasting glucose levels in obese women compared with control subjects (52). Haloperidol has also been reported to be associated with higher glucose levels in schizophrenia subjects than control subjects during the glucose tolerance test (53). Increased insulin resistance in peripheral tissues can be caused by hyperprolactinemia (54, 55) and may be involved in the mechanism underlying hyperglycemia in patients treated with typical antipsychotics. Alternatively, our observation of increased glucose after haloperidol could be related to the low baseline levels in the haloperidol subgroup; we cannot exclude the possibility that regression to the mean underlies this increase.

We also found statistically significant increases in mean cholesterol levels after treatment with olanzapine and clozapine, which remained overall within normal clinical range. There was no elevation in cholesterol levels with risperidone and haloperidol. Weight gain at endpoint was significantly related to cholesterol elevations in the clozapine group and marginally in the olanzapine group. A similar association between elevated cholesterol and weight gain during olanzapine treatment was reported by Kinon et al. (48). Our findings are consistent with open-label and retrospective data demonstrating a greater association of olanzapine and clozapine treatment than risperidone treatment with increases in cholesterol and triglycerides (32, 56). Henderson et al. (57) found significant increases in both fasting cholesterol and triglycerides in a group of 81 patients treated with clozapine. It appears that the more pronounced effect of antipsychotic treatments on lipid metabolism may be on triglycerides (58–61), which were not measured in the present study. Meyer (32) postulated that antipsychotics with a dibenzodiazepine-derived structure (e.g., clozapine, olanzapine) may be associated with significant elevating effects on fasting triglyceride levels and with lesser effects on cholesterol levels.

Limitations of our study include the attrition of our study group during period 2. Although the attrition was governed by clinical factors, it was comparable among the four treatment groups. Given that attrition, we feel that the data for period 1 are more robust. In addition, period 2 allowed for a variable dose of the antipsychotic medication in contrast to the fixed-dose design of period 1. This may have been an additional factor influencing our results. Finally, the duration of 8 weeks for period 1 was relatively short and may not have been sufficient to allow for more changes in glucose and cholesterol levels to emerge.

Given the concerns regarding endocrine dysregulation in the context of treatment with atypical medications, we recommend that baseline and 6-month monitoring of fasting plasma glucose levels, glycated hemoglobin, fasting cholesterol, and triglycerides be obtained in routine clinical practice with all antipsychotics in order to monitor the risk for development of hyperglycemia and hypercholesterolemia. Fasting insulin assessment, a particularly sensitive measure for glucose control dysregulation, should be performed in patients at particular risk. Baseline weight and regular follow-up weight measurements are further recommended. Given the serious implications for morbidity and mortality attributable to diabetes and elevated cholesterol, clinicians need to be aware of these risk factors when treating patients with chronic schizophrenia.

|

|

|

|

Presented at a New Research session at the 154th Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, New Orleans, May 5–10, 2001. Received April 10, 2002; revision received July 24, 2002; accepted Aug. 1, 2002. From the Nathan Kline Institute for Psychiatric Research; New York University, New York; the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill; Dorothea Dix Hospital, Chapel Hill, N.C.; Manhattan Psychiatric Center, New York; Duke University and John Umstead Hospital, Durham, N.C.; and the Psychiatric Institute and Columbia University, New York. Address reprint requests to Dr. Lindenmayer, Psychopharmacology Research Unit, Nathan Kline Institute for Psychiatric Research, Wards Island, New York, NY 10035; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by NIMH grant MH-53550, by University of North Carolina Mental Health and Neuroscience Clinical Research Center grant MH-33127, and by the Foundation of Hope, Raleigh, N.C. The authors thank Janssen Pharmaceutica Research Foundation, Eli Lilly and Co., Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corp., and Merck and Co. for their donations of medications.Eli Lilly and Co. contributed supplemental funding that covered approximately 18% of the total cost of this study. Overall experimental design, data acquisition, statistical analyses, and interpretation of the results were implemented without any input from any of the pharmaceutical companies. The authors thank Linda Kline, R.N., M.S., C.S., chief coordinator of the project.

1. Kasanin J: The blood sugar curve in mental disease, II: the schizophrenic (dementia praecox) groups. Arch Neurol Psychiatry 1926; 16:414-419Crossref, Google Scholar

2. Thonnard-Neumann E: Phenothiazines and diabetes in hospitalized women. Am J Psychiatry 1968; 124:978-982Link, Google Scholar

3. Braceland FJ, Meduna LJ, Vaichulis JA: Delayed action of insulin in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1945; 102:108-110Link, Google Scholar

4. Dixon L, Weiden P, Delahanty J, Goldberg R, Postrado L, Lucksted A, Lehman A: Prevalence and correlates of diabetes in national schizophrenia samples. Schizophr Bull 2000; 26:903-912Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Tabata H, Kikuoka M, Kikuoka H, Bessho H, Hirayama J, Hanabusa T, Kubo K, Momotani Y, Sanke T, Nanjo K, et al: Characteristics of diabetes mellitus in schizophrenic patients. J Med Assoc Thai 1987; 70(suppl 2):90-93Google Scholar

6. Mukherjee S, Decina P, Bocola V, Saraceni F, Scapicchio PL: Diabetes mellitus in schizophrenic patients. Compr Psychiatry 1996; 37:68-73Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Ai D, Roper TA, Riley JA: Diabetic ketoacidosis and clozapine. Postgrad Med J 1998; 74:493-494Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Colli A, Cocciolo M, Franconbaniera F, Rogantin F, Cattalini N: Diabetic ketoacidosis associated with clozapine treatment (letter). Diabetes Care 1999; 22:176-177Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Kamran A, Doraiswamy PM, Jane JL, Hammett EB, Dunn L: Severe hyperglycemia associated with high doses of clozapine (letter). Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:1395Medline, Google Scholar

10. Koval MS, Rames LJ, Christie S: Diabetic ketoacidosis associated with clozapine treatment. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:1520-1521Medline, Google Scholar

11. Maule S, Giannela R, Lanzio M, Villari V: Diabetic ketoacidosis with clozapine treatment. Diabetes Nutr Metab 1999; 12:187-188Medline, Google Scholar

12. Melkersson KI, Hulting AL, Brismar KE: Different influences of classical antipsychotics and clozapine on glucose-insulin homeostasis in patients with schizophrenia or related psychoses. J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 60:783-791Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Mohan D, Gordon H, Hindley N, Baker A: Schizophrenia and diabetes mellitus. Br J Psychiatry 1999; 174:180-181Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Peterson GA, Byrd SL: Diabetic ketoacidosis from clozapine and lithium cotreatment (letter). Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:737-738Medline, Google Scholar

15. Pierides M: Clozapine monotherapy and ketoacidosis. Br J Psychiatry 1997; 171:90-91Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Popli A, Konicka PE, Jurjus GS, Fuller MA, Jaskiw GE: Clozapine and associated diabetes mellitus. J Clin Psychiatry 1997; 58:108-111Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Smith H, Kenney-Herbert J, Knowles L: Clozapine induced diabetic ketoacidosis. Aust NZ J Psychiatry 1999; 33:120-121Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Thompson J, Chengappa KNR, Good CB, Baker RW, Kiewe RP, Bezner J, Schooler NR: Hepatitis, hyperglycemia, pleural effusion, eosinophilia, hematuria and proteinuria occurring early in clozapine treatment. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1998; 13:95-98Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Wirshing DA, Spellberg BJ, Erhart SM, Marder SR, Wirshing WC: Novel antipsychotics and new onset diabetes. Biol Psychiatry 1988; 44:778-783Crossref, Google Scholar

20. Yazici KM, Erbas T, Yazici AH: The effect of clozapine on glucose metabolism. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes 1998; 106:475-477Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Bettinger TL, Mendelson SC, Dorson PG, Crismon ML: Olanzapine-induced glucose dysregulation. Ann Pharmacother 2000; 34:865-867Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Fertig MK, Brooks VG, Shelton PS: Hyperglycemia associated with olanzapine. J Clin Psychiatry 1998; 59:687-689Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Gatta B, Rigalleau V, Gin H: Diabetic ketoacidosis with olanzapine treatment. Diabetes Care 1999; 22:1002-1003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Goldstein LE, Sporn J, Brown S, Kim H, Finkelstein J, Gaffey GK, Sachs G, Stern TA: New-onset diabetes mellitus and diabetic ketoacidosis associated with olanzapine treatment. Psychosomatics 1999; 40:438-443Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Hayek DV, Hutll V, Reiss J, Schweiger HD, Fuebl HS: Hyperglycemia and ketoacidosis on olanzapine. Nervenarzt 1999; 70:836-837Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Melkersson KI, Hulting AL, Brismar KE: Elevated levels of insulin, leptin, and blood lipids in olanzapine-treated patients with schizophrenia or related psychoses. J Clin Psychiatry 2000; 61:742-749Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Ober SK, Hudak R, Rusterholtz A: Hyperglycemia and olanzapine (letter). Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:970Link, Google Scholar

28. Procyshyn RM, Pane S, Tse G: New onset diabetes mellitus associated with quetiapine. Can J Psychiatry 2000; 45:668-669Medline, Google Scholar

29. Sobel M, Jaggers ED, Franz M: New onset diabetes mellitus associated with initiation of quetiapine treatment. J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 60:556-557Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Croarkin PE, Jacobs DM, Bain B: Diabetic ketoacidosis associated with risperidone treatment. Psychosomatics 2000; 41:369-370Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Kostakoglu AE, Yazici KM, Erbas T, Guvener N: Ketoacidosis as a side effect of clozapine: a case report. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1996; 93:217-218Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Meyer JM: A retrospective comparison of lipid, glucose, and weight changes at one year between olanzapine and risperidone treated inpatients, in Proceedings of the 39th Annual Meeting of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. Nashville, Tenn, ACNP, 2000Google Scholar

33. Wilson DR, Hammond C, D’Souza L, Sarkar N: New-onset diabetes and ketoacidosis with atypical antipsychotics, in Proceedings of the 39th Annual Meeting of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. Nashville, Tenn, ACNP, 2000Google Scholar

34. Iqbal N, Oldan RL, Baird G, Schwartz B, Baloy L, Bhagoji B, Simjee M: Diabetes mellitus induced by atypical antipsychotics, in 2000 Annual Meeting Syllabus and Proceedings Summary. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 2000Google Scholar

35. Lindenmayer J-P, Nathan A, Smith RC: Hyperglycemia associated with the use of atypical antipsychotics. J Clin Psychiatry 2001; 62(suppl 23):30-38Google Scholar

36. Burke JP, Williams K, Gaskill SP, Hazuda HP, Haffner M, Stern MP: Rapid rise in the incidence of type 2 diabetes from 1987 to 1996: results from the San Antonio Heart Study. Arch Intern Med 1999; 159:1450-1456Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Lund BC, Perry PJ, Brooks JM, Arndt S: Clozapine use in patients with schizophrenia and the risk of diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and hypertension. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001; 58:1172-1176Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Kwong K, Cavazzoni P, Hornbuckle K, Hutchins D, Signa W, Kotsanos J, Breier A: Higher incidences of diabetes mellitus during exposure to antipsychotics—findings from a retrospective cohort study in the US, in Abstracts of the 41st New Clinical Drug Evaluation Unit Meeting. Rockville, Md, National Institute of Mental Health, 2001, poster III-8Google Scholar

39. Gianfrancesco F, Grogg A, Mahmaoud R, Markowitz J, Nasrallah HA: Association of new-onset diabetes and antipsychotics: findings from a large health plan database, in Abstracts of the 41st New Clinical Drug Evaluation Unit Meeting. Rockville, Md, National Institute of Mental Health, 2001, poster III-79Google Scholar

40. Breier A, Kwong K, Hornbuckle K, Cavazonni P, Carlson C, Wu J, Kotsanos J, Holman R: A retrospective cohort study of diabetes mellitus and antipsychotic treatment in the United Kingdom (poster), in Abstracts of the 40th Annual Meeting of the American College of Neuropsychiatry. Nashville, Tenn, ACNP, 2001Google Scholar

41. Smith RC, Lindenmayer J-P, Khandat A, Wahab M, Bodala P, Rosenberger J: A prospective study of glucose and lipid metabolism with atypical and conventional antipsychotics (poster), in Proceedings of the 14th Annual Research Conference of the New York State Office of Mental Health. Albany, New York State Office of Mental Health, 2001Google Scholar

42. Volavka J, Czobor P, Sheitman B, Lindenmayer J-P, Citrome L, McEvoy JP, Cooper TB, Chakos M, Lieberman JA: Clozapine, olanzapine, risperidone, and haloperidol in the treatment of patients with chronic schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159:255-262Link, Google Scholar

43. Kay SR, Opler LA, Lindenmayer J-P: Reliability and validity of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale for schizophrenics. Psychiatry Res 1988; 23:99-110Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

44. Report of the Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care 2002; 25:S5-S20Google Scholar

45. Czobor P, Volavka J, Sheitman B, Lindenmayer JP, Citrome L, McEvoy J, Cooper TB, Chakos M, Lieberman JA: Antipsychotic-induced weight gain and therapeutic response: a differential association. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2002; 22:244-251Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

46. Newcomer JW, Haupt DW, Fucetola R, Melson AK, Schweiger JA, Cooper BP, Selke G: Abnormalities in glucose regulation during antipsychotic treatment of schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2002; 59:337-345Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

47. Harris MI, Flegal KM, Cowie CC, Eberhardt MS, Goldstein DE, Little RR, Wiedmeyer HM, Byrd-Holt DD: Prevalence of diabetes, impaired fasting glucose and impaired glucose tolerance in US adults. Diabetes Care 1998; 21:518-524Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

48. Kinon BJ, Basson BR, Gilmore JA, Tollefson GD: Long-term olanzapine treatment: weight change and weight-related health factors in schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry 2001; 62:92-100Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

49. Karenyi C, Lowenstein B: Chlorpromazine induced diabetes. Dis Nerv Syst 1968; 29:827-828Medline, Google Scholar

50. Baldessarini RJ, Lipinski JF: Toxicity and side effects of antipsychotic, antimanic, and antidepressant medications. Psychiatr Annals 1976; 6:484-493Google Scholar

51. Boucharlat J, Chatelain R: [An exceptional neuroleptic accident: diabetes insipidus induced by thioridazine.] Annales Medico-Psychologiques 1968; 1:306 (French)Google Scholar

52. Baptista T, Lacruz A, Angeles F, Silvera R, de Mendoza S, Mendoza MT, Hernandez L: Endocrine and metabolic abnormalities involved in obesity associated with typical antipsychotic drug administration. Pharmacopsychiatry 2001; 34:223-231Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

53. Brambilla F, Guastalla A, Guerrini A, Riggi F, Rovere C, Zanoboni A, Zanoboni-Muciaccia W: Glucose-insulin metabolism in chronic schizophrenia. Dis Nerv Syst 1976; 37:98-103Medline, Google Scholar

54. Foss MC, Paula FJ, Paccola GM, Piccinato CE: Peripheral glucose metabolism in human hyperprolactinemia. Clin Endocrinol 1995; 43:721-726Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

55. Schernthaner G, Prager R, Punzengruber C, Luger A: Severe hyperprolactinemia is associated with decreased insulin binding in vitro and insulin resistance in vitro. Diabetologia 1985; 28:138-142Medline, Google Scholar

56. Wozniak KM, Linnoila M: Hyperglycemic properties of serotonin receptor antagonists. Life Sci 1991; 49:101-109Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

57. Henderson DC, Cagliero E, Gray C, Nasrallah RS, Hayden DL, Schoenfeld DA, Goff DC: Clozapine, diabetes mellitus, weight gain, and lipid abnormalities: a five-year naturalistic study. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:975-981Link, Google Scholar

58. Ghaeli P, Dufresne RL: Serum triglyceride levels in patients treated with clozapine. Am J Health System Pharm 1996; 53:2079-2081Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

59. Sheitman BB, Bird PM, Binz W, Akinli L, Sanchez C: Olanzapine-induced elevation of plasma triglyceride levels (letter). Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:1471-1472Abstract, Google Scholar

60. Osser DN, Najarian DM, Dufresne RL: Olanzapine increases weight and serum triglyceride levels. J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 60:767-770Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

61. Clark ML, Ray TS, Paredes A, Ragland RE, Castiloe JP, Smith CW, Wolf S: Chlorpromazine in women with chronic schizophrenia: the effect on cholesterol levels and cholesterol-behavior relationships. Psychosom Med 1967; 29:634-642Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar