A Prospective Study of Childhood Neurocognitive Functioning in Schizophrenic Patients and Their Siblings

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study evaluated childhood cognitive functioning in individuals who later developed schizophrenia and in their unaffected siblings. METHOD: Through the National Collaborative Perinatal Project, seven subtests of the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children were administered at age 7 to 32 individuals who developed schizophrenia in adulthood, 25 of their nonschizophrenic siblings, and 201 demographically similar nonpsychiatric comparison subjects. Mixed model analysis was used to examine between-group differences in standardized scores on the subtests. RESULTS: The probands and unaffected siblings had lower scores for picture arrangement, vocabulary, and coding than the comparison subjects but differed from each other only on the coding subtest. CONCLUSIONS: Children who later developed schizophrenia and their siblings showed similar patterns of deficits involving spatial reasoning, verbal knowledge, perceptual-motor speed, and speeded processes of working memory. However, the probands exhibited more severe deficits in perceptual-motor speed and speeded processes of working memory than their unaffected siblings.

Previous analyses of data from the National Collaborative Perinatal Project, a large population-based birth cohort, have revealed a general IQ deficit in the premorbid period of schizophrenia, before the onset of overt psychotic symptoms (1, 2). While these studies provide clear evidence for cognitive dysfunction in the premorbid period, the cognitive domains and developmental time points at which these deficits present themselves during the premorbid period are unclear. Previous research has shown that patients with schizophrenia and some of their healthy siblings exhibit greater deficits in executive function, attention, and verbal memory than in other functions (3, 4). In this study we primarily aimed to determine whether a similar profile of deficits is present during childhood in individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia as adults and to evaluate the degree to which such deficits are shared by their unaffected siblings. Accordingly, we analyzed the profile of Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (WISC) subtest scores at age 7 for individuals from the Philadelphia cohort of the National Collaborative Perinatal Project who later developed schizophrenia and for their healthy siblings and demographically similar healthy comparison subjects.

Method

Data collection procedures, which were approved by the University of Pennsylvania institutional review board, have been described in detail previously (1, 5) and will only be summarized briefly. The original 9,239 individuals enrolled at the Philadelphia site of the National Collaborative Perinatal Project (6) were screened for contacts with public mental health facilities in Philadelphia from 1985 to 1995. This search yielded 72 individuals who received a DSM-IV diagnosis (confirmed by chart review) of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. These probands had 63 siblings not diagnosed with schizophrenia who also participated in the National Collaborative Perinatal Project study.

Of the original cohort members, 79% (N=7,326) were assessed with seven subtests (i.e., information, vocabulary, comprehension, digit span, picture arrangement, block design, and coding) of the WISC (7) at age 7. Each proband (N=32) and each sibling (N=25) with WISC information available was matched with at least three nonpsychiatric comparison subjects on gender, ethnicity, age at examination, and socioeconomic status. The resulting groups of probands, siblings, and comparison subjects were similar in terms of mean age at the time of testing (7.6 years [SD=1.5], 7.4 years [SD=1.5], and 7.5 years [SD=1.4], respectively), percentage of female subjects (34% [N=11], 48% [N=12], and 41% [N=70], respectively), and percentage of African Americans (100% for each group). Socioeconomic status was determined according to the method of Myrianthopoulos and French (8); the values were similar for the probands (mean=37.3, SD=19.4), siblings (mean=37.9, SD=16.4), and comparison subjects (mean=37.5, SD=17.2). The groups differed in percentage of left-handed subjects (31% [N=10], 12% [N=3], and 9% [N=16], respectively) and mean overall IQ (84.6 [SD=2.5], 85.8 [SD=2.7], and 92.2 [SD=1.7], respectively). The full-scale IQs of the matched comparison subjects did not differ significantly from those of comparison subjects omitted from the analysis.

Other methodological issues, including incomplete ascertainment of probands, use of chart review methods for diagnoses, and overrepresentation of minorities in the study group, have been discussed in detail previously (1, 5).

The relationship between diagnostic outcome and cognitive functioning according to the seven WISC subtests was investigated by using mixed model analysis, which accounts for the dependence of observations from siblings within the same family by modeling family as a random variable. Gender, ethnicity, handedness, age at examination, and socioeconomic status were included as covariates. For a significant interaction of diagnosis and subtest, two-tailed t tests were performed to compare the mean subtest z scores of the different diagnostic groups.

Results

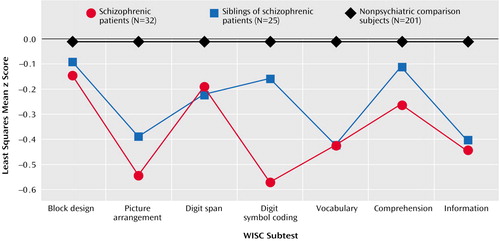

Figure 1 shows the least squares mean z score for each diagnostic group on each WISC subtest. After we controlled for gender, ethnicity, age at examination, handedness, and socioeconomic status, there was an overall main effect of diagnosis (F=9.50, df=2, 2051, p=0.0001) and a significant interaction of diagnosis and subtest (F=2.50, df=18, 2051, p=0.0004), indicating that the pattern of z scores across subtests differed among the diagnostic groups.

When we compared the subtest scores of the probands and normal comparison subjects, t tests (df=2051 for all) showed significant differences for the picture arrangement (t=–3.88, p=0.0001), vocabulary (t=–2.85, p=0.005), and coding (t=–6.08, p=0.0001) subtests but not for the block design (t=–0.95, p=0.34), information (t=–1.09, p=0.27), comprehension (t=–0.77, p=0.44), and digit span (t=–0.48, p=0.63) subtests. Similarly, the unaffected siblings performed significantly worse than the comparison subjects on the picture arrangement (t=–2.85, p=0.005), vocabulary (t=–2.90, p=0.004), and coding (t=–2.19, p=0.03) subtests but not on the block design (t=–0.91, p=0.36), information (t=–0.73, p=0.47), comprehension (t=–0.21, p=0.84), and digit span (t=–0.33, p=0.74) subtests. Finally, the probands performed significantly worse than their unaffected siblings only on the coding subtest (t=–2.64, p=0.009) and not on the block design (t=0.05, p=0.96), picture arrangement (t=–0.48, p=0.63), information (t=–0.20, p=0.84), comprehension (t=–0.39, p=0.70), vocabulary (t=0.30, p=0.76), and digit span (t=–0.08, p=0.94) subtests.

Discussion

These results expand our earlier findings (1) by demonstrating that probands showed premorbid deficits on the WISC picture arrangement, vocabulary, and coding subtests at age 7 in relation to normal comparison subjects. While each of these subtests engages a complex array of cognitive functions, the probands’ worse performance on the coding subtest in relation to that of their siblings appears to reflect the probands’ greater deficit in perceptual-motor speed and speeded processes of working memory, as this test requires online maintenance of relevant information in order to facilitate rapid set-shifting. This pattern is also observed in high-risk adolescents (9) and adult patients with schizophrenia (4). Deficient performance on the picture arrangement subtest is consistent with a deficit in mental sequencing; however, because of the social nature of the stimuli, deficits on this task may also imply a disturbance in social cognition, which is compatible with evidence of impaired social functioning in the prodromal period among patients who later develop schizophrenia (10). In addition to these processes, poor performance on the vocabulary subtest at age 7, with normal performance on the information and comprehension subtests, suggests focal deficits in language acquisition. While the vocabulary subtest reflects crystallized verbal knowledge in adults, at age 7 it may index acquisition of word meanings. This finding appears compatible with prior evidence of delayed language development in children who later develop schizophrenia (5).

Notably, the unaffected siblings exhibited deficits in the same domains of functioning. This pattern is consistent with findings from a number of neuropsychological studies of adult schizophrenic patients and their first-degree relatives, which show that relatives are intermediate between patients and healthy subjects on nearly every test examined (3); this pattern suggests a genetic contribution to the neurocognitive deficits in schizophrenia. Taken together, these findings suggest a striking degree of continuity in the deficit profiles of at-risk subjects from childhood through adulthood.

Both the future patients and their siblings showed impairment in complex visual-motor processing and speeded executive processes of working memory, but the future patients were impaired more than their siblings. Because this study evaluated discordant siblings, rather than monozygotic co-twins, it is not clear whether this greater deficit in the future schizophrenic patients is due to a greater genetic predisposition to schizophrenia in the future patients, differential exposure to environmental etiological agents, or both. On the basis of work with monozygotic twins discordant for schizophrenia, a genetic origin of the greater impairment in visual-spatial processing in the future patients appears most likely (4).

Presented at the International Congress on Schizophrenia Research, Colorado Springs, Colo., March 29 to April 2, 2003. Received Jan. 16, 2003; revision received June 11, 2003; accepted June 20, 2003. From the Department of Psychology and the Department of Psychiatry and Biobehavioral Sciences, UCLA; and the Department of Psychiatry and the Department of Psychology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. Address reprint requests to Dr. Cannon, Department of Psychology, UCLA, 1285 Franz Hall, Box 951563, Los Angeles, CA 90095; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by grants from the March of Dimes Birth Defects Foundation and the Stanley Foundation.

Figure 1. Standardized Scores on Subtests of the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (WISC) for 7-Year-Olds Who Later Developed Schizophrenia, Their Unaffected Siblings, and Nonpsychiatric Comparison Children

1. Cannon TD, Bearden CE, Hollister JM, Rosso IM, Sanchez LE, Hadley T: Childhood cognitive functioning in schizophrenia patients and their unaffected siblings: a prospective cohort study. Schizophr Bull 2000; 26:379–393Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Seidman LJ, Buka SL, Goldstein JM, Horton NJ, Reider RO, Tsuang MT: The relationship of prenatal and perinatal complications to cognitive functioning at age 7 in the New England cohorts of the National Collaborative Perinatal Project. Schizophr Bull 2000; 26:309–321Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Kremen WS, Seidman LJ, Pepple JR, Lyons MJ, Tsuang MT, Faraone SV: Neuropsychological risk indicators for schizophrenia: a review of family studies. Schizophr Bull 1994; 20:103–119Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Cannon TD, Huttunen MO, Lonnqvist J, Tuulio-Henriksson A, Pirkola T, Glahn D, Finkelstein J, Heitanen M, Kaprio J, Koskenvuo M: The inheritance of neuropsychological dysfunction in twins discordant for schizophrenia. Am J Hum Genet 2000; 67:369–382Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Bearden CE, Rosso IM, Hollister JM, Sanchez LE, Hadley T, Cannon TD: A prospective cohort study of childhood behavioral deviance and language abnormalities as predictors of adult schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 2000; 26:395–410Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Niswader KR, Gordon M: The Collaborative Perinatal Study of the National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke: The Women and Their Pregnancies. Philadelphia, WB Saunders, 1972Google Scholar

7. Wechsler D: Manual for the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children. New York, Psychological Corp, 1949Google Scholar

8. Myrianthopoulos NC, French KS: An application of the US Bureau of the Census socioeconomic index to a large, diversified patient population. Soc Sci Med 1968; 2:283–299Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Cornblatt BA, Malhotra AK: Impaired attention as an endophenotype for molecular genetic studies of schizophrenia. Am J Med Genet 2001; 105:11–15Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Dworkin RH, Lewis JA, Cornblatt BA, Erlenmeyer-Kimling L: Social competence deficits in adolescents at risk for schizophrenia. J Nerv Ment Dis 1994; 182:103–108; correction, 182:301Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar