Predictors and Correlates of Suicide Attempts Over 5 Years in 1,237 Alcohol-Dependent Men and Women

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: In previous studies, factors related to a history of suicide attempts in persons with alcohol dependence have included sociodemographic variables, a more severe course of alcoholism, additional substance use disorders, and psychiatric comorbidity. This 5-year prospective study evaluated attributes associated with suicide attempts in a group of treatment-seeking persons with alcohol dependence. Psychiatric comorbidity was examined in terms of a distinction between substance-induced and independent psychiatric disorders. METHOD: Semistructured interviews were conducted with 1,237 alcohol-dependent subjects from the Collaborative Study on the Genetics of Alcoholism both at an initial evaluation and at a 5-year follow-up. Clinically relevant information was gathered at baseline, and suicidal behavior, aspects of alcohol dependence, and drug use were evaluated at the follow-up interview. RESULTS: Alcohol-dependent subjects (N=56) with suicide attempts during the follow-up period were more likely than subjects with no suicide attempts (N=1,181) to have made prior attempts. Other factors related to future suicide attempts in univariate analyses included younger age, being separated or divorced, other drug dependence, substance-induced psychiatric disorders, and indicators of a more severe course of alcoholism. Gender did not predict future attempts. CONCLUSIONS: A 5-year prospective evaluation of attributes associated with suicide attempts among alcohol-dependent persons identified factors that contributed to a small but significant proportion of the variance for future suicidal behavior.

Almost 40% of treatment-seeking patients with an alcohol use disorder report ever having attempted suicide, a rate that is six- to tenfold higher than the rate of suicide attempts in the general population (1–6). Prior attempts are powerful predictors of suicide completion (7–9), with between 10% and 15% of attempters dying by suicide within the next 10 years (10). Approximately 5% of those with alcohol use disorders die by suicide (11, 12), and 20% to 35% of completed suicides are carried out by individuals with alcoholism (13, 14).

A relatively extensive literature, primarily from retrospective studies, has described characteristics that relate to suicide attempts and completions (6, 15, 16). Although suicide attempters are most often young and female, and suicide completers are typically older and male, some attributes overlap across those populations (17). In addition to a history of a substance use disorders (11, 18, 19), these factors include the absence of a marriage (6, 7, 13, 14), being unemployed (7, 14, 20), and being Caucasian (16). Some personality disorders (e.g., antisocial personality disorder) are associated with both repeated attempts and with suicide completions, and others (e.g., borderline personality disorder) are more likely to be observed in repeated attempters. Several axis I conditions are more closely tied to completion, including mood disorders and schizophrenia (8, 14, 21–23).

The relationship of suicidal behavior to depressive disorders is complex. At least two types of mood syndromes with different prognoses in relation to suicide and different optimal treatments have been described (8, 11, 18, 24, 25). Depressions that are observed only in the context of intoxication or withdrawal from alcohol (i.e., alcohol-induced mood disorders) can look cross-sectionally identical to independent depressive episodes and often present with the same levels of hopelessness and suicidal ideation. However, alcohol-induced conditions are likely to improve dramatically within several days to a month of abstinence (25–28). Substance-induced conditions are more likely to be seen with heavier intake of alcohol and with concomitant drug dependencies, while independent depression in alcoholic individuals is associated with an earlier onset of suicidal behavior and a higher number of attempts (25, 26).

Three prospective investigations reported higher risk for future suicide attempts in substance-dependent persons with mood disorders, in younger persons, and in those who were not married, but these studies reported no differences in risk related to race or gender (20, 27, 29). A fourth large prospective study of armed forces conscripts reported that completion was predicted by alcohol or drug dependence, depressive syndromes, and psychotic disorders (12). Finally, investigations of smaller clinical groups of subjects with prior suicidal behavior confirmed a higher future rate of suicide completion and highlighted the importance of substance use disorders, single marital status, and personality disorders in predicting suicide attempts (7, 10, 30–35).

This paper used follow-up data from the Collaborative Study on the Genetics of Alcoholism to evaluate characteristics associated with suicide attempts. The following three hypotheses were tested: 1) a history of suicide attempts at baseline will be a powerful predictor of future attempts, even when considered in the context of other demographic and clinical characteristics; 2) new attempts will be predicted by demographic characteristics (female gender, younger age, being separated or divorced, and being unemployed), psychiatric diagnoses (especially substance-induced conditions), evidence of a more severe course of alcohol dependence, and a history of additional substance use disorders; and 3) similar characteristics observed during follow-up will correlate with new suicide attempts.

Method

The Collaborative Study on the Genetics of Alcoholism is a family pedigree investigation that enrolls treatment-seeking alcohol-dependent probands who meet the DSM-III-R and Feighner criteria for alcohol dependence (19, 25, 36). Probands are recruited at six centers in the United States. The only exclusions are for life-threatening medical disorders, repeated intravenous drug use, and an inability to speak English. Comparison subjects have been identified from driver’s license records, attendance at a dental clinic, random mailings, and other approaches (25). All enrollees provided written informed consent to participate in the study.

Probands and their relatives were interviewed at baseline by using the Semi-Structured Assessment for the Genetics of Alcoholism, which focuses on demography, substance use patterns, and the assessment of 17 axis I DSM-III-R diagnoses, as well as antisocial personality disorder (37, 38). Comparison subjects were interviewed in the same format at baseline. The interviewer also asked about past suicidal behavior and recorded data on the number of instances of past suicidal behavior, the age at the most recent suicidal event, the need for medical treatment, the subject’s intent to die, and the method used.

Additional sections of the Semi-Structured Assessment for the Genetics of Alcoholism were used to determine the age at onset of substance use disorders (i.e., the age by which three or more criterion items were met) and of other psychiatric conditions; a time line was used to distinguish between substance-induced and independent psychiatric disorders (25). Psychiatric syndromes that occurred only during active alcohol dependence were considered to have been substance-induced; independent disorders were those that occurred either before the onset of alcohol dependence or during a ≥3-month period of abstinence.

The probands, comparison subjects, and appropriate relatives were reassessed a mean of 5.4 years (SD=0.6) after the initial interview. Only original probands or comparison subjects, their first-degree relatives, and offspring age ≤20 years in the participating families were eligible for follow-up. Because individuals with antisocial personality disorder have especially high rates of suicidal behavior and a more severe course of alcoholism (39), they were excluded. Of the 3,190 alcohol-dependent subjects at baseline (19), 1,046 were excluded from the analyses because not enough time had passed for the follow-up and 511 were not eligible for follow-up (e.g., they were nonproband family members age ≤20 years or their parents). An additional 127 subjects could not be interviewed because they were deceased, leaving 1,506 eligible for follow-up interviews. Four subjects were known to have died by suicide, two of whom had prior attempts. Of the 1,506 remaining individuals, 1,237 were successfully evaluated (82.1%) with a follow-up interview that was similar to the baseline interview with the Semi-Structured Assessment for the Genetics of Alcoholism but that emphasized events that occurred during the interval. This group included probands, relatives of probands, and comparison subjects, all of whom met DSM-III-R and Feighner criteria for alcohol dependence.

The 1,237 alcohol-dependent persons were divided into two groups on the basis of their reports of suicide attempts during the follow-up. Differences across groups were evaluated by using chi-square tests for categorical data and Student’s t tests for continuous variables. Separate simultaneous forced entry multivariate logistic regression analyses, conducted with SPSS 10.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago), were used to determine the baseline characteristics and relevant attributes that best predicted the experience of a suicide attempt during follow-up.

Results

The 1,237 subjects with a follow-up interview resembled the subjects who were not followed (19) in the proportion with prior suicide attempts, gender distribution, proportion who were probands, and most alcohol, drug, and psychiatric characteristics at baseline. Compared with the group that was not followed, the group that was followed was slightly younger (mean=37.1 years, SD=11.5, versus mean=39.8 years, SD=12.6) (t=–6.35, df=2813.8, p<0.001), more educated (mean=13.0 years, SD=2.3, versus mean=12.5 years, SD=2.3) (t=–5.54, df=3188.0, p<0.001), and more likely to be Caucasian (78.1% versus 74.6%) (χ2=4.98, df=1, p<0.05); had an earlier onset of alcohol dependence (mean=23.0 years, SD=7.9, versus mean=24.1 years, SD=8.6) (t=–3.48, df=2783.7, p<0.001); and reported a lower maximum number of drinks per day at baseline (mean=25.3, SD=19.3, versus mean=26.9, SD=19.7) (t=–2.15, df=3187.0, p<0.05). Those who were followed included a slightly lower proportion of subjects with independent psychiatric disorders (19.3% versus 22.3%) (χ2=4.10, df=1, p<0.05).

Fifty-six subjects (4.5%), more than half of whom reported prior attempts at baseline, reported having attempted suicide during the follow-up. Those with no prior attempts reported an average of 1.0 attempts (SD=1.3) during the follow-up; 62.9% of those attempts resulted in hospitalization. The methods for the most serious attempts during the follow-up were taking pills (50.0%) and wrist cutting or stabbing (23.2%); 42.8% reported that they had a serious wish to die, 12.5% noted no lethal intent, and the remainder reported varying degrees of lethality.

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the subjects who did and did not attempt suicide during the follow-up. Those with attempts during the 5-year follow-up period were younger, more likely to be a proband, and more likely to be separated or divorced. The table corroborates the predicted higher level of past difficulties with alcohol. Compared with the subjects who did not attempt suicide, the subjects who attempted suicide had an earlier onset of alcohol abuse, reported a higher maximum number of drinks per day, reported more alcohol-related physical problems, and met a greater number of the nine DSM-III-R alcohol dependence criteria. Those with suicide attempts were more likely than those without attempts to report each alcohol dependence criterion except use in larger amounts, a desire to cut down, and interference with role performance (data not shown). Subjects with suicide attempts also reported a higher number of nine possible withdrawal symptoms during their worst abstinence syndrome (19), were more likely to ever have had alcohol-related treatment, and reported more drug dependencies. Finally, more subjects with suicide attempts fulfilled the criteria for a substance-induced psychiatric condition; the only between-group difference for independent disorders was a greater likelihood of panic disorder among the subjects who attempted suicide than among those who did not.

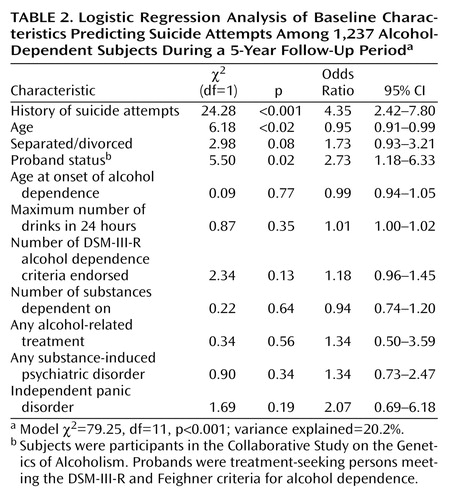

Table 2 presents the results of a forced-entry logistic regression analysis in which 11 items that significantly differentiated between groups in Table 1 were entered as potential predictors of suicide attempts. Items from Table 1 that were excluded because of multicollinearity included the age at onset of regular drinking, withdrawal symptoms, physical problems, and specific drug dependencies. The three characteristics that contributed to the logistic regression equation, explaining 20.2% of the variance, were age, proband status, and prior suicide attempts. When the latter was excluded, the pseudo R2 decreased to 15.1%. Finally, because 70.4% of the probands were men, it is possible that the lack of an effect of gender might relate to the inclusion of proband status in the equation. Therefore, the logistic regression analysis was repeated with data for the 822 nonprobands (54.7% of whom were men), with the result that the same items performed well and gender still did not enter the equation.

For comparison, the variables presented in Table 1 and Table 2 were reevaluated in a group of 2,000 participants in the Collaborative Study on the Genetics of Alcoholism who had never had an alcohol use disorder. During follow-up, 16 subjects (0.8%) attempted suicide, a rate lower than that reported in Table 1 for the alcohol-dependent subjects (χ2=48.82, df=1, p<0.001). In the subjects who had never had an alcohol use disorder, the items that related to suicide attempts included a prior history of attempts, younger age, number of substance use disorders, and any independent or substance-induced psychiatric disorder. Three items (the number of substance dependencies, the number of independent axis I disorders, and prior attempts) combined to explain 22.2% of the variance (χ2=29.96, df=8, p<0.001).

While they are not prospective in nature, data on subject characteristics during the 5-year follow-up period may provide additional useful findings. As shown in Table 3, a younger age and being separated or divorced were related to suicide attempts, as were a higher number of alcohol dependence items endorsed and a higher rate of meeting each of the nine criteria (data not shown). Compared with the subjects who had not attempted suicide, those with suicide attempts were more likely to receive alcohol-related treatment and had used and were dependent on a higher number of illicit substances. Finally, the subjects who had attempted suicide were more likely to have had substance-induced and independent depressive episodes during the follow-up period.

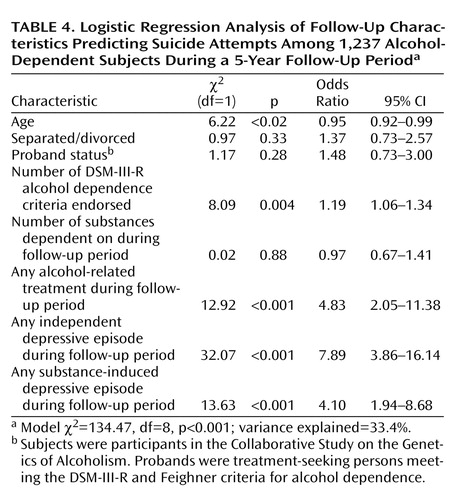

Table 4 presents the results of a logistic regression analysis using all seven nonoverlapping variables from Table 3 that significantly differentiated between groups, along with proband status, as this stable trait had significantly distinguished subjects with suicide attempts in analyses presented in Table 1. Items not entered because of multi-collinearity included the number of illicit substances used, history of independent and substance-induced depressive episodes, and specific drugs of dependence. The five items that entered the equation, explaining 33.4% of the variance, were younger age, two items indicating more severe alcohol problems, and two items indicating the presence of a substance-induced or an independent depressive episode during the follow-up period. Finally, the equation was recalculated by using data for the nonprobands. Gender was allowed to enter the equation, but this new item did not become significant, and the R2 decreased to 20.0%. The other items entering the equation were similar to those in the regression analysis of the proband data.

Table 5 relates the results of a final logistic regression analysis predicting suicide attempts. The equation included all items that significantly entered the analyses reported in Table 2 and Table 4. The six items that significantly entered the equation in the final analysis, explaining 36.4% of the variance, were history of suicide attempts, age at baseline, number of DSM-III-R alcohol dependence criteria met during the follow-up period, alcohol-related treatment during the follow-up period, and any independent or substance-induced depressive episode during the follow-up period.

Discussion

This paper presents results from what is to our knowledge the only 5-year prospective study of suicide attempts that included a large number of alcohol-dependent men and women. The initial, or baseline, characterization of these alcohol-dependent subjects was carried out with a detailed semistructured interview, a similar instrument was used at the time of follow-up, and substance-induced and independent psychiatric conditions were considered independently.

During the 5 years, 4.5% of these alcohol-dependent men and women attempted suicide. This rate compares to a rate of suicide attempts of 1.9% in a 13-year prospective study of a general population community sample (20). Thus, consistent with prior reports, the alcoholic subjects appear to have experienced a relatively high rate of suicide attempts.

As hypothesized, a past history of suicide attempts was an excellent predictor of such behavior during follow-up. More than half of the alcoholics who attempted suicide during the follow-up had prior attempts, compared with only 14% of the subjects with no prior suicidal behavior. An individual with a prior attempt had a 15.2% risk for a new attempt during the follow-up, compared with a 2.6% risk for the subjects without a prior attempt. The importance of prior attempts as a predictor of future suicidal behavior is supported by the robust performance of this item in the regression analyses.

Most of the baseline characteristics that were associated with suicide attempts in the past also predicted new attempts. These included younger age, evidence of a more severe course of alcoholism, being separated or divorced, and histories of additional substance use disorders.

The data presented in Table 1 support a correlation between suicide attempts during the follow-up and substance-induced depression, mania, and panic disorder, but not most independent psychiatric conditions. The data presented in Table 3 underscore the importance of both substance-induced and independent depressions during follow-up. Although the distinction between induced and independent conditions is imperfect, short-term prospective studies have demonstrated that the former are more likely to clear with abstinence and are less closely related to family histories of independent mood disorders (25, 40). The closer association between suicide attempts and a prior history of substance-induced psychiatric conditions may occur because these disturbances, which appear during intense intoxication, are more prevalent than independent disorders.

A few background characteristics that have been associated with suicide attempts did not predict attempts during the follow-up. Consistent with the findings of some other studies (17, 20, 35), female gender was associated with a history of suicide attempts but it was not related to suicidal behavior during the follow-up. Also, being unemployed at baseline was not related to future attempts, although we can suggest no obvious explanations for this finding. Finally, some studies have indicated a higher rate of suicide attempts among Caucasians (16, 20, 32), but, like some other investigators (27, 29), we did not find this association in the current study group.

The third hypothesis was supported by the similarity between the attributes that related to suicide attempts at baseline and those that were related to suicide attempts during the follow-up.

It is important to remember that suicide attempts are difficult to predict. In this study, regression analyses limited to characteristics documented at baseline explained only 20% of the variance, and even the combination of baseline and follow-up attributes explained only 36%. Thus, even in the best-case scenario, almost 65% of the events and characteristics that related to the suicide attempts in the current study group were unknown.

The results must be considered in light of some caveats. First, subjects with antisocial personality disorder were excluded, the Collaborative Study on the Genetics of Alcoholism population is unique in that most families had a high percentage of family members with alcoholism, and individuals with severe life-threatening disorders or associated characteristics were excluded. These decisions may have affected the generalizability of results. Second, the data came from self-reports elicited by using the Semi-Structured Assessment for the Genetics of Alcoholism, and the results might have been different if information had been available from other informants or from medical record reviews. Regarding this concern, however, a recent analysis from the Collaborative Study on the Genetics of Alcoholism revealed few impressive differences in major diagnoses when data from all available resources and records were considered (41). Third, some of the persons who died during the follow-up may have committed suicide, and it is possible that if these subjects had been recognized some of the results might have changed. Fourth, only a subset of subjects had been interviewed long enough ago to be appropriate for follow-up, although the group that was followed was similar in most characteristics to those who were not followed. Finally, because, thankfully, only four subjects committed suicide during the follow-up, the analysis was based on information regarding suicide attempts only, and suggestions about predictors of completed suicide cannot be made.

|

|

|

|

|

Received April 3, 2002; revision received July 30, 2002; accepted Aug. 14, 2002. From the VA San Diego Healthcare System and the University of California, San Diego. Address reprint requests to Dr. Schuckit, Department of Psychiatry (116A), VA San Diego Healthcare System, 3350 La Jolla Village Dr., San Diego CA 92161; [email protected] (e-mail). The Collaborative Study on the Genetics of Alcoholism (H. Begleiter, State University of New York, Health Sciences Center at Brooklyn, principal investigator; T. Reich, Washington University, St. Louis, co-principal investigator) includes nine centers where data collection, analysis, and/or storage take place. The nine sites and principal investigators and co-investigators are Indiana University (T.-K. Li, J. Nurnberger, Jr., P.M. Conneally, H. Edenberg); University of Iowa (R. Crowe, S. Kuperman); University of California San Diego (M. Schuckit); University of Connecticut (V. Hesselbrock); State University of New York Health Sciences Center at Brooklyn (B. Porjesz, H. Begleiter); Washington University in St. Louis (T. Reich, C.R. Cloninger, J. Rice, A. Goate); Howard University (R. Taylor); Rutgers University (J. Tischfeld); and Southwest Foundation (L. Almasy). This national collaborative study is supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism grants AA-08403 and AA-05526 and by the Research Service of the Department of Veterans Affairs. Dr. Preuss was supported by grant GEP-PR 607/1 from Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft.

1. Driessen M, Veltrup C, Weber J, John U, Wetterling T, Dilling H: Psychiatric co-morbidity, suicidal behaviour and suicidal ideation in alcoholics seeking treatment. Addiction 1998; 93:889-894Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Hasegawa K, Mukasa H, Nakazawa Y, Kodama H, Nakamura K: Primary and secondary depression in alcoholism—clinical features and family history. Drug Alcohol Depend 1991; 27:275-281Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Preuss UW, Koller G, Bahlmann M, Soyka M, Bondy B: No association between suicidal behavior and 5-HT2A-T102C polymorphism in alcohol dependents. Am J Med Genet 2000; 96:877-878Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Roy A: Relation of family history of suicide to suicide attempts in alcoholics. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:2050-2051Link, Google Scholar

5. Inskip HM, Harris EC, Barraclough B: Lifetime risk of suicide for affective disorder, alcoholism and schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry 1998; 172:35-37Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Kessler RC, Borges G, Walters EE: Prevalence of and risk factors for lifetime suicide attempts in the National Comorbidity Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999; 56:617-626Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Johnsson-Fridell EJ, Öjehagen A, Träskman-Bendz L: A 5-year follow-up study of suicide attempts. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1996; 93:151-157Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Foster T, Gillespie K, McClelland R, Patterson C: Risk factors for suicide independent of DSM-III-R axis I disorder: case-control psychological autopsy study in Northern Ireland. Br J Psychiatry 1999; 175:175-179Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Suokas J, Suominen K, Isometsa E, Ostamo A, Lonnqvist J: Long-term risk factors for suicide mortality after attempted suicide—findings of a 14-year follow-up study. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2001; 104:117-121Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Nordström P, Samuelsson M, Åsberg M: Survival analysis of suicide risk after attempted suicide. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1995; 91:336-340Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Rossow I, Amundsen A: Alcohol abuse and suicide: a 40-year prospective study of Norwegian conscripts. Addiction 1995; 90:685-691Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Allebeck P, Allgulander C: Suicide among young men: psychiatric illness, deviant behaviour and substance abuse. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1990; 81:565-570Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Pirkola SP, Isometsa ET, Heikkinen ME, Lönnqvist JK: Suicides of alcohol misusers and non-misusers in a nationwide population. Alcohol Alcohol 2000; 35:70-75Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Caces FE, Harford T: Time series analysis of alcohol consumption and suicide mortality in the United States, 1934-1987. J Stud Alcohol 1998; 59:455-461Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Murphy GE, Wetzel RD: The lifetime risk of suicide in alcoholism. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1990; 47:383-392Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Moscicki EK: Identification of suicide risk factors using epidemiologic studies. Psychiatr Clin North Am 1997; 20:499-517Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Beautrais AL, Joyce PR, Mulder RT, Fergusson DM, Deavoll BJ, Nightingale SK: Prevalence and comorbidity of mental disorders in persons making serious suicide attempts: a case-control study. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:1009-1014Link, Google Scholar

18. Roy A: Characteristics of cocaine-dependent patients who attempt suicide. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:1215-1219Link, Google Scholar

19. Preuss UW, Schuckit MA, Smith TL, Danko GP, Buckman K, Bierut L, Bucholz KK, Hesselbrock MN, Hesselbrock VM, Reich T: Comparison of 3,190 alcohol-dependent individuals with and without suicide attempts. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2002; 26:471-477Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Kuo WH, Gallo JJ, Tien AY: Incidence of suicide ideation and attempts in adults: the 13-year follow-up of a community sample in Baltimore, Maryland. Psychol Med 2001; 31:1181-1191Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Conner KR, Cox C, Duberstein PR, Tian L, Nisbet PA, Conwell Y: Violence, alcohol, and completed suicide: a case-control study. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:1701-1705Link, Google Scholar

22. Hesselbrock M, Hesselbrock V, Syzmanski K, Weidenman M: Suicide attempts and alcoholism. J Stud Alcohol 1988; 49:436-442Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Roy A, Lamparski D, DeJong J, Moore V, Linnoila M: Characteristics of alcoholics who attempt suicide. Am J Psychiatry 1990; 147:761-765Link, Google Scholar

24. Ohberg A, Vuori E, Ojanperä I, Lonnqvist J: Alcohol and drugs in suicides. Br J Psychiatry 1996; 169:75-80Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Schuckit MA, Tipp JE, Bergman M, Reich W, Hesselbrock VM, Smith TL: Comparison of induced and independent major depressive disorders in 2,945 alcoholics. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:948-957Link, Google Scholar

26. Preuss UW, Schuckit MA, Smith TL, Danko GP, Dasher AC, Hesselbrock MN, Hesselbrock VM, Nurnberger JI Jr: A comparison of alcohol-induced and independent depression in alcoholics with histories of suicide attempts. J Stud Alcohol 2002; 63:498-502Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Andrews JA, Lewinsohn PM: Suicidal attempts among older adolescents: prevalence and co-occurrence with psychiatric disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1992; 31:655-662Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Brown SA, Inaba RK, Gillin JC, Schuckit MA, Stewart MA, Irwin MR: Alcoholism and affective disorder: clinical course of depressive symptoms. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:45-52Link, Google Scholar

29. Petronis KR, Samuels JF, Moscicki EK, Anthony JC: An epidemiologic investigation of potential risk factors for suicide attempts. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1990; 25:193-199Medline, Google Scholar

30. De Moore GM, Robertson AR: Suicide in the 18 years after deliberate self-harm: a prospective study. Br J Psychiatry 1996; 169:489-494Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Rygnestad T: A prospective 5-year follow-up study of self-poisoned patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1988; 77:328-331Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Borowsky IW, Ireland M, Resnick MD: Adolescent suicide attempts: risks and protectors. Pediatrics 2001; 107:485-493Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Ravndal E, Vaglum P: Overdoses and suicide attempts: different relations to psychopathology and substance abuse? a 5-year prospective study of drug abusers. Eur Addict Res 1999; 5:63-70Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Wichstrom L: Predictors of adolescent suicide attempts: a nationally representative longitudinal study of Norwegian adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2000; 39:603-610Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Húlten A, Jiang GX, Wasserman D, Hawton K, Hjelmeland H, De Leo D, Ostamo A, Salander-Renberg E, Schmidtke A: Repetition of attempted suicide among teenagers in Europe: frequency, timing and risk factors. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2001; 10:161-169Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Feighner JP, Robins E, Guze SB, Woodruff RA Jr, Winokur G, Muñoz R: Diagnostic criteria for use in psychiatric research. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1972; 26:57-63Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Bucholz KK, Cadoret R, Cloninger CR, Dinwiddie SH, Hesselbrock VM, Nurnberger JI, Reich T, Schmidt I, Schuckit MA: A new, semi-structured psychiatric interview for use in genetic linkage studies: a report on the reliability of the SSAGA. J Stud Alcohol 1994; 55:149-158Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Hesselbrock M, Easton C, Bucholz KK, Schuckit M, Hesselbrock V: A validity study of the SSAGA—a comparison with the SCAN. Addiction 1999; 94:1361-1370Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Virkkunen M, Goldman D, Linnoila M: Serotonin in alcoholic violent offenders. Ciba Found Symp 1996; 194:168-177Medline, Google Scholar

40. Brown SA, Schuckit MA: Changes in depression among abstinent alcoholics. J Stud Alcohol 1988; 49:412-417Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41. Nurnberger JI Jr, O’Connor S, Meyer ET, Reich T, Rice J, Schuckit M, King L, Petti T, Bierut L, Bucholz K: A family study of alcoholism: diagnosing relatives with family history information alone (abstract). Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2002; 26:23AGoogle Scholar