Contact With Mental Health and Primary Care Providers Before Suicide: A Review of the Evidence

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study examined rates of contact with primary care and mental health care professionals by individuals before they died by suicide. METHOD: The authors reviewed 40 studies for which there was information available on rates of health care contact and examined age and gender differences among the subjects. RESULTS: Contact with primary care providers in the time leading up to suicide is common. While three of four suicide victims had contact with primary care providers within the year of suicide, approximately one-third of the suicide victims had contact with mental health services. About one in five suicide victims had contact with mental health services within a month before their suicide. On average, 45% of suicide victims had contact with primary care providers within 1 month of suicide. Older adults had higher rates of contact with primary care providers within 1 month of suicide than younger adults. CONCLUSIONS: While it is not known to what degree contact with mental health care and primary care providers can prevent suicide, the majority of individuals who die by suicide do make contact with primary care providers, particularly older adults. Given that this pattern is consistent with overall health-service-seeking, alternate approaches to suicide-prevention efforts may be needed for those less likely to be seen in primary care or mental health specialty care, specifically young men.

Suicide is a serious public health problem. Among industrialized countries in 1990, suicide was among the top 10 causes of death (1). In 1998 approximately 30,000 people died by suicide in the United States, making it the eighth leading cause of death (2). Recently, the National Strategy for Suicide Prevention was issued (3), outlining specific goals intended to prevent suicide in the United States. Programs aimed at improving the ability of primary care and mental health professionals to identify and treat those at risk for suicide are recommended. A primary goal of this review was to consider the potential of such strategies. Although general estimates of service contact before suicide are often cited (4, 5), there has been no systematic review of how frequently different types of health care professionals have contact with various populations who eventually commit suicide. At least one review has examined contacts with health and mental health care providers before suicide (6); however, its usefulness was limited because it did not take into consideration specific populations that eventually commit suicide, such as older adults or youth, who may differ in their rates of health care contact.

Despite limited systematic reviews of health care contacts before suicide, some prevention strategies involving health care providers have been suggested. On the basis of studies of psychological autopsies and record reviews from general practitioner sites, it has been recommended that detecting and treating depression in primary care may be effective in preventing elderly suicides, since a majority of older adults seek primary care services within a month of suicide (7). Others have recommended that improved detection and treatment of depression by primary care practitioners may reduce suicides among women, but not men, since women are more likely to seek health services (8). It would seem that a systematic review of the evidence of health care contacts among suicide decedents of various age groups, and between men and women, could be helpful in a consideration of prevention approaches.

To that end, this review examined rates of contact with primary and specialty mental health care providers of individuals before their suicide. Contact information within 1 month of death and within the year of suicide was reviewed. Given the importance of diagnosis and treatment of mental disorders in preventing suicide, lifetime contact with mental health services was also examined.

Method

Literature Search

Relevant studies were identified by using several electronic databases, including MEDLINE, PsycINFO, and the Social Sciences Citation Index, from the years of their inception through May 2000. The search included articles related to completed suicide and health or mental health care contact and was limited to studies in the English language.

Criteria for Inclusion

Only studies of groups of individuals who completed suicide were included in the review. Data regarding nonfatal suicidal behaviors (e.g., suicide attempts, suicidal ideation) were not included because the individuals who complete suicide often have different characteristics than those who exhibit nonfatal suicidal behaviors (9, 10). Only studies that included at least one estimate of mental health or primary care contact before suicide were included.

In order to increase the generalizability of the review, only studies that reflected a defined epidemiological group were included. Excluded were studies that were duplicative of prior reports with regard to information on health service contact and those that used groups selected for specific diagnoses, insured groups, or suicide victims with previous contact with a certain psychiatric hospital (e.g., clinical follow-up studies).

Characteristics of Studies

Criteria for classifying deaths as suicides varied across studies. In a number of studies, only deaths classified by the medical examiner as suicides were included. Other studies included both deaths classified as suicides and deaths classified as “undetermined” (in the United States) or “open” (in the United Kingdom) that were judged to be suicides. Studies were based in Europe, Australia, and the United States. Although it would have been desirable to limit this review to U.S. study groups only in order to increase the review’s relevance to interventions in the U.S. health care system, few studies containing relevant data were available.

Three main types of studies were included in this review: psychological autopsies, record reviews, and record reviews plus additional sources of information. Studies were considered psychological autopsies if the investigators interviewed at least one individual who had a personal relationship with the deceased as a primary source of data. Record review studies used medical examiner’s or coroner’s reports as the sole source of data. Studies with record review plus supplemental data included studies that used medical examiners’ reports as the primary source of data but supplemented this data with information from a number of other sources. Additional sources of information included interviews with physicians or mental health professionals, physician or mental health provider case notes, and preexisting databases of health records.

Presentation of Results

Data are presented according to percentage of suicide victims who had contact with health care providers during each time period. Information reported during the interval between the last contact and suicide completion varied widely from study to study. In order to increase comparability across studies, several periods were selected for summary. Time periods included within 1 month from last contact and within 1 year from last contact, and, for mental health care contact, cumulative lifetime contact was also recorded. Mental health care contact included both outpatient and inpatient service use.

Summaries were broken down by age group and separately by gender. Data were clustered into three age groups: age 35 and under, age 55 and older, and the full age range. Although it would have been desirable to examine more specific age groups, as well as possible gender-by-age-group effects, there were insufficient data available for such analyses.

Results

As of May 2000, 40 studies had been found that fit our criteria and contained data on the duration between the individuals’ last contact with mental health or primary care professionals and their suicide (9, 11–52). Of these, four were classified as a record review only, 21 were classified as a record review plus supplemental data, and 15 were classified as psychological autopsies. An informal analysis of rates of contact across different types of methods suggested that rates were fairly comparable across methods, except when looking at primary care contact, in which studies of psychological autopsies appeared to report slightly higher rates of contact than the other two methods. We reported means for time periods that had two or more measurement points to contribute to the computation of the average. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to examine differences in rates of health care contact among the groups.

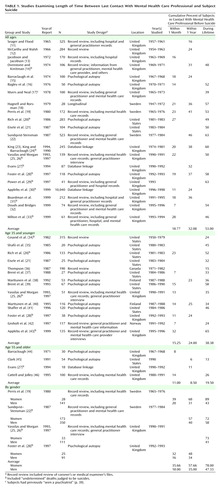

Contact With Mental Health Services

Reports on study groups representing the full age range showed that overall rates of contact with mental health services within 1 month before suicide averaged approximately 19% (range=7%–28%), and in the year before suicide, rates of contact averaged 32% (range=16%–46%). Lifetime rates of contact with mental health services averaged 53% (range=39%–63%) (Table 1). For persons age 35 and younger on average, approximately 15% (range=7%–32%) had seen a mental health professional within 1 month of suicide. The average rate of contact within 1 year of suicide was 24% (range=23%–25%). Lifetime rates of mental health care contact averaged about 38% (range=15%–65%) (Table 1).

For persons age 55 and older, mental health contact within the last month averaged 11% (range=8%–14%) for the two U.K. studies containing data. Contact with mental health services within 1 year of suicide averaged 8.5% (range=6%–11%). Compared to mental health services contact for persons age 35 and younger (24%), older persons tended to have had less contact with mental health services within the year before suicide (8.5%) (z=1.96, p=0.05). Lifetime rates were not much more frequent, with an average of 19.5% (range=13%–26%) (Table 1).

For men versus women, gender comparisons were limited to studies that included suicide decedents across the lifespan. On average, 36% (range=32%–39%) of the women and 18% (range=16%–20%) of the men had some contact with mental health services within 1 month of their suicide. Within 1 year of suicide, an average of 58% (range=48%–68%) of the women and 35% (range=31%–40%) of the men had contact with mental health services. Lifetime rates of mental health care also were higher among female suicides: 78% of the women (range=72%–89%) and 47% of the men (range=41%–58%). For lifetime contact (78% and 47%, respectively), as well as contact in the year before suicide (58% and 35%), the women were more likely than the men to have had contact with mental health care (z=1.96, p=0.05, for both comparisons) (Table 1).

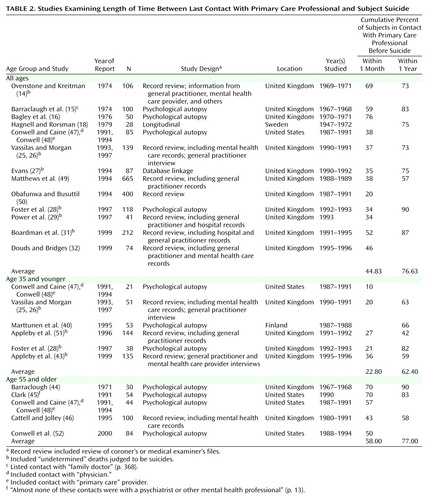

Contact With Primary Care Providers

Across all age groups, contact with primary care providers in the month before suicide averaged approximately 45% (range=20%–76%). The rate of contact with primary care providers within 1 year of suicide averaged approximately 77% (range=57%–90%) (Table 2). For persons age 35 and younger, contact with primary care providers within 1 month of suicide averaged about 23% (range=10%–36%), and an average of about 62% (range=42%–82%) had contact with primary care providers up to a year before their suicide (Table 2). For persons age 55 and older, within 1 month of suicide an average of 58% (range=43%–70%) of older adults had contact with primary care providers, which was significantly greater than those age 35 and younger (23%) (z=2.62, p<0.05). A majority of older adults, 77% (range=58%–90%) had contact with primary care providers in the year before their suicide (Table 2). For the men versus the women, on the basis of the two studies available, 100% of the women had contact with a primary care provider within 1 year of suicide, while 78% (range=69%–87%) of the men had contact with primary care providers in the year before their suicide.

Discussion

This review suggests that contact with health care services in the year before suicide is common. Rates of contact are much higher for primary care providers, relative to mental health services. This is consistent with that fact that in the United States (53) and the United Kingdom (54), persons with mental health problems are more likely to seek services in the primary care sector, rather than from mental health professionals. The second key finding is that rates of contact varied by age and gender.

Contact With Mental Health Services

Approximately one-third of the suicide decedents across these studies had contact with mental health services within a year of their suicide, and about one in five had contact within the month of death. Overall rates of contact varied among different age groups and across genders. Persons age 35 and younger tended to have higher rates of contact with mental health services within a year of death than suicide decedents age 55 and older. This age effect may be a cohort effect, since the younger group lived in a time when mental health issues became less stigmatized. Lifetime mental health service rates of contact for women tended to be higher than for men.

Contact With Primary Health Care Services

A greater portion of individuals who committed suicide had contact with primary care providers in the months before their suicide than with mental health specialists. Across the full age range, about one-half had contact with a primary care professional within 1 month of their suicide, and about three-quarters had contact within 1 year of suicide. These rates varied across age groups, with older adults having higher rates of primary care contact than younger adults in the month before their suicide. This suggests that interventions involving primary care professionals have the potential to significantly affect suicide rates for older adults. The two studies reviewed that included information on decedent gender and primary care contact indicate that women decedents tend to have higher rates of contact with primary care providers and thus may benefit more from prevention activities aimed at primary care practices. This interpretation is consistent with the Gotland Study (55), in which an educational program on the treatment of depression aimed at primary care practitioners appeared to mainly affect suicide rates of women.

Elderly men have the highest rate of suicide in the United States (2) and the United Kingdom (56); thus high rates of suicide for groups with a broad age range may be at least partially due to the inclusion of older adults in these calculations. Of interest, one U.S. study (34) reported that elderly suicide decedents who had not seen a doctor within 6 months of death had a reputation of having avoided doctors all of their lives.

Limitations

The studies reviewed only reported contacts with health services professionals by suicide decedents and did not describe the characteristics of all persons who sought care. As a result, we cannot determine if contacts with mental health or primary care providers had any preventative effects. However, recent U.S. estimates of age and gender characteristics of those who use medical care services have indicated that women and persons age 65 and older are more likely to use medical care than men and individuals under the age of 18 (57, 58). These patterns are generally consistent with the pattern of rates of contact by suicide decedents in the reviewed studies.

Several caveats must be considered when an attempt is made to generalize beyond the study groups included in this review. First, different methods may have resulted in different reported rates of contact. Second, none of the studies provided information on the rates of health care contact for racial or ethnic minority suicide victims. On the basis of reports that minorities in the United States have lower levels of primary care and mental health care usage (59, 60), rates of contact with health services by ethnic and racial minority suicide decedents may be lower than those reported here. Third, this study did not address the rates of contact for more specific groups of interest. The group containing subjects age 35 and younger included multiple developmental periods, including adolescence and young adulthood. The onset of high-risk disorders, such as bipolar disorder or schizophrenia, is often in early adulthood. While it would be preferable to examine such subgroups, since they may have different patterns of contact with health care services, limited data precluded this effort.

Future Research Needs

To our knowledge, there are no U.S. studies that provide estimates for rates of contact for mental health services across the full age range in the year before suicide, and only one U.S. study (47, 48) provided contact estimates across the full age range with primary care services in the year before suicide. More data, as well as more recent data, are also needed, since the patterns of primary care and mental health care contact have changed significantly because of the rise of managed care in the United States (61).

Learning more about “mechanisms of action” in the contacts between health care providers and individuals at risk, including the protective processes that stop individuals from acting on suicidal thoughts, could improve suicide-prevention efforts. Determining rates of contact with specific subgroups of professionals (e.g., internists, social workers) might also be helpful in enhancing training for these specialties, as recommended in the National Strategy for Suicide Prevention(3). Obtaining additional information, such as insurance status and treatment adherence, could also enhance understanding of the role of service use in preventing suicide.

Summary

Only one-third of suicide decedents had contact with mental health services within the year of their death, while over 75% had contact with primary care providers. If current trends in health care contact continue (57, 58), suicide-prevention efforts involving primary care may be most effective in preventing suicide among older adults and possibly women. Alternative prevention activities may be needed for younger men at risk for suicide, who are less likely to seek out health care services.

|

|

Received Sept. 28, 2000; revisions received Feb. 9 and Aug. 23, 2001; accepted Nov. 15, 2001. From the Division of Services and Intervention Research, NIMH, and the Catholic University of America, Washington, D.C. Address reprint requests to Dr. Pearson, Division of Services and Intervention Research, NIMH, 6001 Executive Blvd., Rm. 7160, MSC 9635, Bethesda, MD 20892-9635; [email protected] (e-mail). The views in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of NIMH or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

1. Murray CJL, Lopez AD (eds): The Global Burden of Disease: A Comprehensive Assessment of Mortality and Disability From Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors in 1990 and Projected to 2020. Boston, Harvard School of Public Health, 1996Google Scholar

2. Hoyert DL, Kochanek KD, Murphy SL: Deaths: final data for 1997. Natl Vital Stat Rep 1999; 47(19):1-104Google Scholar

3. National Strategy for Suicide Prevention: Goals and Objectives for Action. Rockville, Md, US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, 2001Google Scholar

4. Clark DC, Fawcett J: Review of empirical risk factors for evaluation of the suicidal patient, in Suicide: Guidelines for Assessment, Management, and Treatment. Edited by Bongar B. New York, Oxford University Press, 1992, pp 16-48Google Scholar

5. Hirschfeld RM, Russell JM: Assessment and treatment of suicidal patients. N Engl J Med 1997; 337:910-915Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Pirkis J, Burgess P: Suicide and recency of health care contacts: asystematic review. Br J Psychiatry 1998; 173:462-474Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Pearson JL, Conwell Y, Lyness JM: Lafe-life suicide and depression in the primary care setting. Developments in Geriatric Psychiatry 1997; 76:13-38Google Scholar

8. Rutz W, von Knorring L, Pihlgren H, Rihmer Z, Wålinder J: An educational project on depression and its consequences: is the frequency of major depression among Swedish men underrated, resulting in high suicidality? Primary Care Psychiatry 1995; 1:59-63Google Scholar

9. Duberstein PR, Conwell Y, Seidlitz L, Denning DG, Cox C, Caine E: Personality traits and suicidal behavior and ideation in depressed inpatients 50 years of age and older. J Gerontol 2000; 55B(1):P18-P26Google Scholar

10. Linehan MM: Suicidal people: one population or two? Ann NY Acad Sci 1986; 487:16-33Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Seager CP, Flood RA: Suicide in Bristol. Br J Psychiatry 1965; 111:919-930Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. McCarthy PD, Walsh D: Suicide in Dublin. Br Med J 1966; 1:1393-1396Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Jacobson S, Jacobson DM: Suicide in Brighton. Br J Psychiatry 1972; 121:369-377Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Ovenstone IMK, Kreitman N: Two syndromes of suicide. Br J Psychiatry 1974; 124:336-345Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Barraclaugh B, Bunch J, Nelson B, Sainsbury P: A hundred cases of suicide: clinical aspects. Br J Psychiatry 1974; 125:355-373Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Bagley C, Jacobson S, Rehin A: Completed suicide: a taxonomic analysis of clinical and social data. Psychol Med 1976; 6:429-438Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Myers DH, Neal CD: Suicide in psychiatric patients. Br J Psychiatry 1978; 133:38-44Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Hagnell O, Rorsman B: Suicide in the Lundby study: a comparative investigation of clinical aspects. Neuropsychobiology 1979; 5:61-73Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Perris C, Beskow J, Jacobsson L: Some remarks on the incidence of successful suicide in psychiatric care. Social Psychiatry 1980; 15:161-166Crossref, Google Scholar

20. Rich CL, Young D, Fowler RC: San Diego Suicide Study: young vs old subjects. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1986; 43:577-582Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Eisele JW, Frisino J, Haglund W, Reay DT: Teenage suicides in King County, Washington, II: comparison with adult suicides. Am J Forensic Med Psychol 1987; 8:210-216Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Sundqvist-Stensman UB: Suicides among 523 persons in a Swedish county with and without contact with psychiatric care. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1987; 76:8-14Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. King E: Suicide in the mentally ill: an epidemiological sample and implications for clinicians. Br J Psychiatry 1994; 165:658-663Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. King E, Barraclough B: Violent death and mental illness: a study of a single catchment area over eight years. Br J Psychiatry 1990; 156:714-720Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Vassilas CA, Morgan HG: General practitioners’ contact with victims of suicide. Br Med J 1993; 307:300-301Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Vassilas CA, Morgan HG: Suicide in Avon: life stress, alcohol misuse, and use of other services. Br J Psychiatry 1997; 170:453-455Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Evans J: The health service contacts of 87 suicides. Psychol Bull 1994; 18:548-550Crossref, Google Scholar

28. Foster T, Gillespie K, McClelland R: Mental disorders and suicide in Northern Ireland. Br J Psychiatry 1997; 170:447-452Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Power K, Davies C, Swanson V, Gordon D, Carter H: Case-control study of GP attendance rates by suicide cases with or without a psychiatric history. Br J Gen Pract 1997; 47:211-215Medline, Google Scholar

30. Appleby L, Shaw J, Amos T, McDonnell R, Harris C, McCann K, Kiernan K, Davies S, Bickley H, Parsons R: Suicide within 12 months of contact with mental health services: national clinical survey. Br Med J 1999; 318:1235-1239Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Boardman AP, Grimbaldeston AH, Handley C, Jones PW, Willmott S: The North Staffordshire Suicide Study: a case-control study of suicide in one health district. Psychol Med 1999; 29:27-33Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Douds F, Bridges V: Survey of suicides in the Fife region of Scotland. Psychol Bull 1999; 23:267-269Crossref, Google Scholar

33. Milton J, Ferguson B, Mills T: Risk assessment and suicide prevention in primary care. Crisis 1999; 20:171-177Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Cosand BJ, Bourque LB, Krauss JF: Suicide among youth in Sacramento County, California, 1950-1979. Adolescence 1982; 68:917-930Google Scholar

35. Shafii M, Carrigan S, Whittinghill JR, Derrick A: Psychological autopsy of completed suicide in children and adolescents. Am J Psychiatry 1985; 142:1061-1064Link, Google Scholar

36. Thompson T: Childhood and youth suicide in Manitoba: a demographic study. Can J Psychiatry 1987; 32:264-269Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Brent DA, Perper JA, Goldstein CE, Kolko DJ, Allan MJ, Allman CJ, Zelenak JP: Risk factors for youth suicide: a comparison of youth suicide victims with suicidal inpatients. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988; 45:581-588Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Marttunen MJ, Hillevi M, Aro HM, Lonnqvist JK: Youth suicide: endpoint of long-term difficulties. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1992; 34:649-654Crossref, Google Scholar

39. Brent DA, Perper JA, Moritz G, Allman C, Friend A, Roth C, Schweers J, Balach L, Baugher M: Psychiatric risk factors for youth suicide: a case-control study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1993; 32:521-529Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. Marttunen MJ, Henriksson MM, Hillevi MA, Heikkinen ME, Isometsa ET, Lonnqvist JK: Suicide among female youth: characteristics and comparison with males in the age groups 13 to 22 years. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1995; 34:1297-1307Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41. Shaffer D, Gould MS, Fisher P, Trautmann P, Moeau D, Kleinman M, Flory M: Psychiatric diagnosis in child and youth suicide. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996; 53:339-348Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

42. Groholt B, Ekeberg O, Wichstrom L, Haldorsen T: Youth suicide in Norway, 1990-1992: a comparison between children and youth completing suicide and age- and gender-matched controls. Suicide Life Threat Behav 1997; 27:250-263Medline, Google Scholar

43. Appleby L, Cooper J, Amos T, Faragher B: Psychological autopsy study of suicides by people aged under 35. Br J Psychiatry 1999; 175:168-174Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

44. Barraclough BM: Suicide in the elderly, in Recent Developments in Psychogeriatrics. Edited by Kay DWK, Walk A. Kent, UK, Royal Medico-Psychological Association, 1971, pp 87-97Google Scholar

45. Clark DC: Final report to the Andrus Foundation. Washington, DC, AARP Andrus Foundation, Jan 28, 1991Google Scholar

46. Cattell J, Jolley DJ: One hundred cases of suicide in elderly people. Br J Psychiatry 1995; 166:451-457Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

47. Conwell Y, Caine E: Suicide in the elderly chronic patient population, in The Elderly With Chronic Mental Illness. Edited by Light E, Lebowitz B. New York, Springer, 1991, pp 31-52Google Scholar

48. Conwell Y: Suicide in elderly patients, in Diagnosis and Treatment of Depression in Late Life. Edited by Shneider LS, Reynolds CF, Lebowitz BD, Friedhoff AJ. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1994, pp 397-418Google Scholar

49. Matthews K, Milne S, Ashcroft GW: Role of doctors in the prevention of suicide: the final consultation. Br J Gen Pract 1994; 44:345-348Medline, Google Scholar

50. Obafunwa JO, Busuttil A: Clinical contact preceding suicide. Postgrad Med J 1994; 70:428-432Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

51. Appleby L, Amos T, Doyle U, Tomenson B, Woodman M: General practitioners and young suicides: a preventive role for primary care. Br J Psychiatry 1996; 168:330-333Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

52. Conwell Y, Lyness JM, Duberstein P, Cox C, Seidlitz L, DiGiorgio A, Caine E: Completed suicide among older patients in primary care practices: a controlled study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2000; 48:23-29Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

53. Regier DA, Goldberg ID, Taube CA: The de facto US mental health services system: a public health perspective. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1978; 35:685-693Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

54. Kerwick SW, Jones RH: Educational interventions in primary care psychiatry: a review. Primary Care Psychiatry 1996; 2:107-117Google Scholar

55. Rutz W, Wålinder J, Von Knorring L, Rihmer Z, Pihlgren H: Prevention of depression and suicide by education and medication: impact on male suicidality: an update from the Gotland study 1997. Int J Psychiatry in Clin Practice 1997; 1:39-46Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

56. Dennis MS, Lindesay JL: Suicide in the elderly: the United Kingdom perspective. Int Psychogeriatr 1995; 7:263-274Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

57. Green LA, Fryer GE, Yawn BP, Lanier D, Dovey SM: The ecology of medical care revisited. N Engl J Med 2001; 34:2021-2024Crossref, Google Scholar

58. Cherry DK, Burt CW, Woodwell DA: National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey:1999 Summary. Advance Data From Vital and Health Statistics Number 322, July 17, 2001. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ad/ad322.pdf Google Scholar

59. Freiman MP: The demand for healthcare among racial/ethnic subpopulations. Health Serv Res 1998; 33:867-890Medline, Google Scholar

60. Wagner TH, Guendelman S: Healthcare utilization among Hispanics: findings from the 1994 minority health survey. Am J Manag Care 2000; 6:355-364Medline, Google Scholar

61. Burnam MA, Escarce JJ: Equity in managed care for mental disorders: benefit parity is not sufficient to ensure equity. Health Affairs 1999; 18(5):22-31Google Scholar