Asperger’s Disorder

Although only recently officially recognized in DSM-IV, Asperger’s disorder has a history nearly as long as that of autism. During World War II, Hans Asperger, a Viennese physician, described a group of boys who had marked social problems but rather good language and cognitive skills (1). These “little professors” were rather pedantic and highly verbal and had unusual, all-encompassing, circumscribed interests that were so all-consuming as to interfere with the children’s development in other areas. These boys had awkward motor skills; similar problems were noted in their fathers. Asperger’s original explanation for the condition autistichen Psychopathen, or “autistic personality disorder” (sometimes less correctly translated as “autistic psychopathy”), suggested some points of similarity with the work of Kanner on infantile autism that had appeared 1 year earlier (2), although neither man was aware of the other’s work. Asperger’s original description was published in German, and only a handful of articles on the subject appeared in the English-language journals until Lorna Wing’s highly influential review (3). Interest in the diagnostic concept of Asperger’s disorder subsequently increased, although various factors complicated the interpretation of research; the relationship of this condition to other disorders, notably higher-functioning autism, remains the topic of debate (4). With the inclusion of Asperger’s disorder in both DSM-IV and ICD-10, clinical use of the term has increased dramatically. Asperger’s disorder is defined, as is autism, in terms of social deficits, but early language skills are preserved in Asperger’s disorder; by definition, if both conditions can be diagnosed, autism takes precedence (DSM-IV, ICD-10).

In this report, we present a description of a patient with a relatively classic presentation of Asperger’s disorder. After the case presentation, we briefly summarize current controversies in diagnosis, the validity of the diagnostic concept, implications for treatment, and current research.

CASE PRESENTATION

Robert, age 11 years, 8 months, was seen for evaluation at the request of his parents, who were concerned that despite his apparent academic skills, Robert was increasingly isolated in school. He was the younger of two children born to his parents, both physicians. They provided historical information, including copies of previous evaluations and school records; Robert was participating in an ongoing research project that included psychological, speech-language-communication, and psychiatric assessments and a research magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) protocol.

Background Information

Robert was born after an essentially uncomplicated pregnancy, labor, and delivery. His parents had no concerns about Robert in his first years of life. He said his first words at 1 year and spoke in sentences by 16 months. Bladder and bowel control were achieved between the ages of 3 and 4, although nighttime bladder control was not achieved until almost age 6. Although his motor skills were somewhat awkward and clumsy, his parents reported that he was an early and avid reader who seemed to learn to read through his interest in videotapes; for example, he had read the Chronicles of Narnia in kindergarten.

Social problems were a major source of concern when Robert entered preschool at age 3; in his rather unstructured program, he had major difficulties with peer interaction. His parents sought a more structured setting, where he did somewhat better but was quickly seen as a rather eccentric child, in part because of his special interests. Robert was interested in, and quite knowledgeable about, astronomy by this time. His early interest in astronomy was quite intense, and he would pursue this interest at any opportunity; the interest intruded on essentially all aspects of his life. For example, in any conversation with peers, he inevitably brought the conversation or play around to stars and planets or time and its measurement. Interests since then have included computer games—their rules, programmers, and the companies that produce them.

Robert was enrolled in regular kindergarten and was evaluated for occupational therapy at age 5, when he was noted to have low motor tone. He was seen by a psychiatrist at age 8, when a diagnosis of anxiety disorder was given. Play therapy was undertaken for approximately 1 year and then discontinued when it appeared ineffective. Robert was not identified as having any special educational needs until age 10. Psychological testing was undertaken at age 10 years, 3 months because of various concerns (poor visual-motor skills, difficulties with handwriting, and social isolation). On the WISC-III (5), his verbal IQ was 145, his performance IQ was 119, and his full-scale IQ was 135; the difference between his verbal and nonverbal abilities was statistically significant and relatively unusual. Achievement testing revealed a range of abilities—e.g., his standard score on reading composites was 134, his writing score was 125, his math reasoning score was 159, and his score for written expression was 101. He had significant difficulties with tasks that required visual-motor coordination, including writing. His gross and fine motor problems were of sufficient concern to prompt occupational and physical therapy sessions; his classroom teacher started to make accommodations for him. In some areas he did very well, e.g., he was enrolled in a math program for gifted children.

Medical and Family History

Apart from a history of recurrent croup and erythema multiforme or urticaria, Robert was in good general health. He had never had an EEG or an MRI; there was no question of a seizure disorder. His hearing was within normal limits. Robert’s older brother had a history of some mild motor delays. There was a family history of depression and a history of social difficulties in members of the extended family. There was no family history of autism.

Current Assessment

Robert, who had traveled some distance for the assessment, was seen over a period of several days. He was accompanied by his mother, who provided historical information as well as information on Robert’s current functioning.

Mental status examination.

Robert’s social difficulties were readily apparent during the course of our contact. He responded to adults’ greetings with appropriate, although very short, phrases and then turned to the side with a rather unmodulated smile, which he did not vary much for quite some time. Typically, he did not always respond to other people’s facial expressions or gestures and often did not attend to social stimuli. Robert actively avoided eye contact and seemed to look through people. Most of the time his emotional expressions—vocal as well as gestural—lacked variability and modulation. One notable exception involved some conversation about sadness and hurtful feelings, during which he briefly commented on his difficulty talking about sadness with others and whether it was worth the effort.

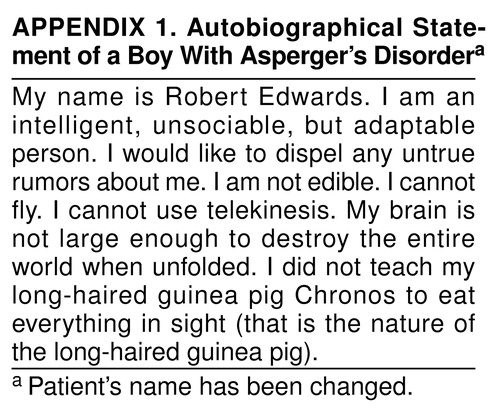

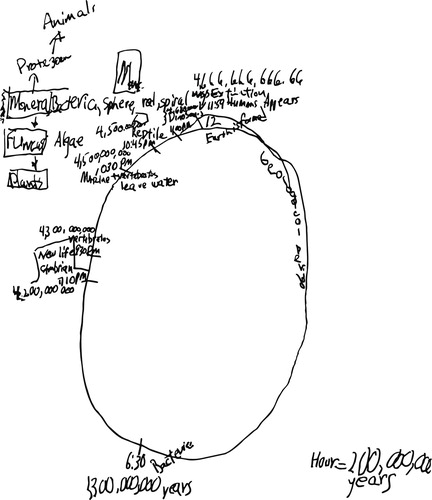

Although initially somewhat quiet and reserved, Robert became much more animated as he felt more comfortable with the examiners (A.K., E.R., and F.R.V.) and situation. He then began to describe his interest in astronomy and, more recently, in time (figure 1.) and engaged in a long monologue describing the history of the universe and the various epochs illustrated in his drawing. Having begun this topic, Robert pursued it with great intensity and vigor, despite repeated attempts by the examiner to redirect the discussion. This interest also appeared repeatedly in his schoolwork, e.g., in an autobiographical statement he had recently prepared (appendix 1).

Robert was able to describe two children he considered his friends, although these relationships appeared to be based almost exclusively on their common interest in computers. His language was quite sophisticated. There were no indications of disorganized thinking. Robert did not exhibit the vegetative signs of depression, although his mood was clearly and predominantly depressed. This seemed to be most evident when he discussed his feelings about school. He described himself as quite isolated and withdrawn in a novel group situation, although he mentioned that he was an excellent public speaker as long as the presentation was a formal one that he could rehearse and memorize in advance.

Robert was not overly preoccupied with extraneous stimuli, could focus on tasks with prompting, and did not exhibit unusual motor behaviors (e.g., self-stimulatory behaviors or tics).

Psychological and speech-language assessments.

Robert’s intellectual abilities were reassessed by means of the WISC-III (5). Scores on this test, and other measures, were consistent with those from previous testing. There was a significant and very unusual discrepancy between his verbal (150) and performance (116) IQs, indicating verbal intelligence skills in the “very superior” range and nonverbal performance skills in the “high average” range. Robert’s verbal skills were all within the “very superior” range, with some ceiling (i.e., perfect) scores. In contrast, there was a great variability in his skills on the performance subtests, with IQs ranging from “average” to “superior.” Performance IQs on a task involving the processing of social situations presented visually and by means of visual-spatial reconstruction were only within the “average” range, and thusrepresented relative deficits.

As part of his participation in a research project, various neuropsychological tests were conducted, and Robert’s performance was notably deficient in two areas. His skills involving visual-motor coordination were 2.5 standard deviations below average, indicating poor manual dexterity and slow speed of motor execution. The second test area involved the abilities of executive function, which were, on average, 1.0–2.5 standard deviations below the mean, reflecting his tendency to perseverate and his poor visual-spatial organization and integration skills.

From the assessment of his speech and communication skills, he was found to be functioning more than 3 standard deviations above the mean in relation to his same-aged peers in terms of his receptive and expressive vocabulary (standard scores of 146 and 141, respectively). Of greater interest, in some respects, was his rather formal and pedantic communication style, e.g., when asked to provide another word for “call,” Robert’s response was “beckon,” and for the word “thin” he provided “dimensionally challenged.” As indicated previously, the overall grammatical structure and linguistic form of Robert’s spontaneous language was noted to be quite sophisticated. On a formal test of his metalinguistic competence, which assessed his overall flexibility of language use, he was also noted to perform above the average range when determining multiple meanings for ambiguous sentences and interpreting a variety of idiomatic expressions. Notable difficulties were observed when a task required the integration of nonverbal information (e.g., facial expressions, gestures, and body proximity) to interpret another’s perspective, to determine appropriate communicative intents, and to identify the choice of relevant topics.

Tests of social cognition and attribution were administered to obtain standard observations of Robert’s ability to interpret social situations. Given the strength of his verbal skills, his performance on an experimental task of social attribution was extremely limited. He failed to appreciate nonverbal cues and to make comments about intentions, social actions, feelings, or any other social elements of a story.

Robert’s mother was the informant for the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales, expanded edition (6). These scales assess the patient’s capacity to engage in the day-to-day activities necessary to take care of oneself and get along with others. It is important to note that for this instrument, the behaviors studied represented typical, rather than optimal, performance of the individual, i.e., scores were based on the degree to which the individual actually engaged in the behavior. In contrast to his strikingly good cognitive and linguistic abilities, Robert exhibited major deficits in adaptive skills. His overall score of 58 (mean=100, SD=15) on this instrument was over 5 standard deviations below that of his full-scale IQ. However, his profile was quite variable, so that, for example, in the communication domain his written language skills were at the level of 14 years, 6 months, whereas the level of his interpersonal abilities was 2 years, 7 months.

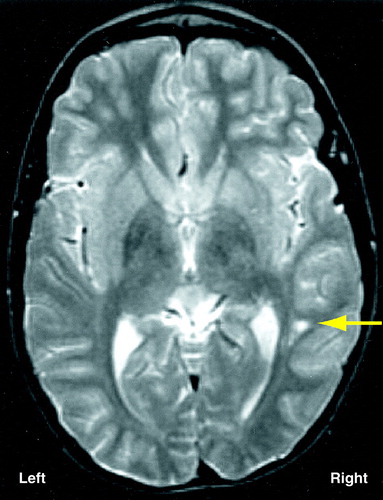

Neuroimaging

As part of our ongoing research on neural mechanisms in social disabilities, proton density and T2-weighted MRI scans of good quality were obtained for Robert. The T2-weighted images showed a focal hyperintensity of about 1 cm, without mass effect, in the right middle temporal gyrus white matter, just lateral to the optic radiations (figure 2.). A repeat evaluation 1 year later revealed an identical lesion that did not enhance with a contrast agent. The significance of a solitary, nonenhancing focal hyperintensity in a young individual without risk factors is unknown, although it certainly could disrupt neural processes in its vicinity. The triangular configuration and the fact that it was also visible on proton density images suggested that it was not a Virchow-Robin space or a cyst. This type of abnormality can be due to a traumatic shear injury, or it might represent focal gliosis due to an infection early in life (7, 8). The fact that it did not enhance with contrast argues against a progressive disease process. This type of lesion is generally stable and can be seen many years later on repeat examinations (7).

DISCUSSION

This case exhibits many of the clinical features typically seen in Asperger’s disorder. Consistent with the original description of Asperger’s disorder (1), the patient exhibited a very severe social disability in the context of excellent overall cognitive and verbal abilities. Although he had the verbal abilities of a 17-year-old, his social skills were at a 3-year-old’s level; this was reflected in his everyday interactions with peers, in which his one-sided and socially naive overtures were rapidly rejected. His verbal ability was the patient’s area of strength in the face of considerable deficits in nonverbal areas; his all-encompassing interest in the stars, planets, and time appeared to actually interfere with the acquisition of skills in other areas and with his ability to interact with others in a more reciprocal fashion. In contrast to what usually occurs with autism, recognition of his difficulties emerged only when he entered preschool, and despite his precocity in some areas, his motor awkwardness was a disability for him.

Although the patient’s diagnostic assignment could be considered relatively straightforward and illustrative of Asperger’s disorder, the use of this diagnostic concept in clinical practice and research has been immersed in a number of controversies; the recent advent of consensual definitions in DSM-IV and ICD-10 has so far failed to resolve a number of issues.

Diagnostic Controversy

Diagnostic controversy stems from several sources. First, “Asperger’s disorder” has been used in very different ways to denote different types of pervasive developmental disorder, e.g., some use the term to refer, essentially, to higher-functioning autism, others to adults with autism, still others to a subthreshold pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified, and yet others to a condition that differs in important ways from autism or pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified (4, 9–11). Yet another difficulty has arisen because individuals from diverse disciplines have also struggled with the problem of categorizing individuals with severe social disability who do not display classic autism; as a result, various terms have arisen to describe similar conditions, e.g., semantic-pragmatic processing disorder (12), right-hemisphere learning problems (13), nonverbal learning disability (14), and the like (reviewed by two of us elsewhere [4]). From the viewpoint of psychiatric taxonomy, the inclusion of Asperger’s disorder is only important if the use of the concept can be supported on the basis of some external validating factor or factors, e.g., differential response to treatment or differences in family history, associated features, patterns of comorbidity, outcome, and the like. While one hopes that the body of work on Asperger’s disorder since Wing’s classic 1981 article (3) might offer final resolution of these issues, it is, unfortunately, not to be.

As we (4) and others (15) have pointed out, various problems have complicated interpretation of the available research on the validity of this diagnosis. These problems include circularity in definition (e.g., when the external validating variable is essentially included in the definition), marked differences in diagnostic practice, and various problems in study design and group description. DSM-IV has been criticized as being overly restrictive (16); with DSM-IV, autism takes precedence over Asperger’s disorder and the criteria for the onset of autism are not well elaborated. In contrast, attempts by others to simply apply the diagnosis of Asperger’s disorder to a socially disabled child with communicative speech at age 2 years seems to err in the opposite direction, i.e., by failing to be more specific about the precise differences between the two conditions, thus leading to overdiagnosis of Asperger’s disorder (4). In our experience, Asperger’s disorder can be differentiated from pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified, in part, because of the greater severity of the social dysfunction, and it can be distinguished from autism by differences in history and current presentation (e.g., the much greater verbosity of individuals with Asperger’s disorder). It is certain that current approaches to diagnosis will be significantly improved by the time DSM-V appears.

Validity of the Diagnostic Concept

Although current data are somewhat contradictory, several lines of evidence suggest important differences among Asperger’s disorder, autism, and pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified. In a DSM-IV field trial, for example, patients with a clinical diagnosis of Asperger’s disorder were found to differ in several ways from those with autism and those with pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified. The patients with Asperger’s disorder had higher verbal performance IQs than those with autism and significantly greater social impairment than those with pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified (10, 17–19). A major problem in interpreting the available work has been the recurrent problem of circularity—that is, when the external validating factors may not necessarily be independent of the definition in the first place. However, several studies have now suggested differences in Asperger’s disorder in several areas. First, verbal skills are often significantly greater than nonverbal ones—a pattern different from that seen in autism, where the reverse is often true (10, 17). Also, although there are apparently strong genetic associations in both conditions, in Asperger’s disorder there appears to be a significantly greater incidence of the disorder in first-degree relatives (20). Finally, there are suggestions of different patterns of comorbidity (4, 21). These differences may have important implications for treatment and research, which lend interest to the condition.

Several studies have shown that patients with Asperger’s disorder have significantly higher verbal IQs than performance IQs, which are often associated with a nonverbal learning disability (9). This is in contrast to autism that is not associated with mental retardation, in which, typically, nonverbal skills are more likely to be higher than or on par with verbal skills (22). Some preliminary results suggest high rates of social disability in family members (20), although the co-occurrence of Asperger’s disorder and autism in the same family has been reported. Considerable interest in various case reports has centered on the issue of comorbidity in Asperger’s disorder, suggesting higher levels of psychosis or violent behavior and many other conditions. Controlled studies are lacking, and in our experience, as in our patient’s case, depression is the most common comorbid condition. Depression is particularly frequent in adolescents and young adults, and, although sometimes overlooked, it can be treated pharmacologically and with structured psychotherapy (4).

Neuroimaging

The white matter lesion of our patient’s right middle temporal gyrus may be related to his clinical and neuropsychological symptoms. The neuropsychological profile in Asperger’s disorder is distinguished from that found in autism by relatively greater verbal than nonverbal skills (4), possibly in relation to fundamental deficits in putative right hemisphere processes (14). Clinical MRIs cannot distinguish adjacent fiber tracts and bundles within the central white matter, but the location of the abnormality suggests that it lies in the inferior longitudinal fasciculus, an ipsilateral association bundle connecting regions of the occipital and temporal lobes. This bundle consists of local corticocortical association loops and more distant association fibers (23), and it is possible that both were disrupted by this lesion. Functional MRI studies indicate that the middle temporal gyrus and the adjacent superior temporal sulcus have a key role in the perception of facial expressions and in the discrimination of the direction of eye gaze (24, 25); these are areas of particular difficulty for individuals with social disabilities. In addition, early focal lesions may have substantial and long-lasting effects on the functioning of distant neural systems, thereby possibly contributing to other aspects of the visible symptoms. For example, early injury to the primate medial-temporal lobe has been shown to disrupt the normal regulation of striatal dopamine activity by the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex during adulthood and to be involved in the genesis of stereotypies (26). Thus, early lesions in one part of the brain may affect the function and integrity of other brain systems. However, in early development the brain is quite plastic, and thus it is difficult to speculate about the precise impact of early brain lesions for any given case.

Implications for Treatment

Although social disabilities in Asperger’s disorder and autistic disorder are defined in the same way, there may be important differences in treatment. In Asperger’s disorder, the cognitive style of treatment is heavily biased toward verbal functioning. Although language skills are relatively preserved and serve as a lifeline for social interaction, there is often a significant discrepancy between the sophistication of linguistic form and structure and the social use of language. Unfortunately, educators (and others) may be misled by the individual’s verbal abilities and may attribute poor social skills and poor performance on nonverbal tasks to negativism or other volitional behaviors; as a result, these individuals may be viewed as behaviorally disordered or “socially emotionally maladjusted” and placed in classes for children with conduct disorders. As we have noted elsewhere (4), this approach might lead to the placement of a child with Asperger’s disorder, a perfect victim, with perfect victimizers. As a result of the child’s growing social isolation, often in the face of some desire for social contact, it is not surprising that the child may become depressed.

In terms of intervention, the better verbal abilities associated with Asperger’s disorder suggest the utility of verbally mediated treatment programs not usually indicated in autism, e.g., very structured and problem-oriented psychotherapy and counseling may be indicated. Verbal skills can be used to teach problem-solving techniques that can be generalized from one situation to another. For example, a child can be taught a set of rules to use to identify contextual cues such as location, facial expressions, body proximity, and gestures to facilitate more appropriate comments, topic initiations, and social inferences. Similar verbal problem-solving techniques can be implemented to help the child cope with more novel or emotionally charged situations. The very explicit verbal approach can be used to help an individual identify and respond appropriately to difficult situations; although such an approach can initially have a rather rehearsed and canned quality, the ability to implement such routines can facilitate an individual’s adaptation. Verbal cues can also be used to help children with Asperger’s disorder complete activities with more challenging motor demands by breaking down each task into specific steps and by promoting verbal self-regulation. Finally, vocational planning should encompass the individual’s strengths and deficits, e.g., presenting problems in visual-motor and visual-spatial integration may be important (27). Although Asperger himself was relatively optimistic about the outcome of Asperger’s disorder, follow-up studies are limited. Nevertheless, the available information suggests that although social difficulties persist, many individuals are capable of adult self-sufficiency and many marry (4). Unfortunately, studies of the differential responses to treatment are still scarce, and the interpretation of outcome studies has been difficult as a result of nosological imprecision. Substantive empirical data would help clarify these issues.

Implications for Research

It will be critical for future research on Asperger’s disorder to integrate the various aspects of the clinical phenomena exhibited into overarching frameworks and models of function or dysfunction. Rigorously designed and controlled studies that address the validity of the diagnostic concept are clearly needed; at present it may be that studies that employ stricter diagnostic criteria are more likely to show important differences between Asperger’s disorder and autism. Information on comorbidity and family genetics will be helpful in this regard. The observation of even higher rates of social disability in Asperger’s disorder than in families with high-functioning autism and the possible genetic relationships of the two conditions are important areas for research. Similarly, better controlled studies of comorbidity may be relevant to genetic research and treatment; the particular constellation of strengths and weaknesses in Asperger’s disorder, relative to those in high-functioning autism, suggests an important area for future research (4). Such differences may also have implications for neuroimaging studies that attempt to elucidate basic pathophysiological mechanisms. Exciting advances in the use of MRI for functional imaging of the brain during discrete cognitive, social, or affective processes provide tools for future studies of the dynamic attributes of the mechanisms that underlie the capacity for socialization and the pathogenesis of autism and Asperger’s disorder (28).

Received Aug. 16, 1999; revision received Dec. 3, 1999; accepted Dec. 17, 1999. From the Child Study Center and the Department of Diagnostic Radiology, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, Conn. Address reprint requests to Dr. Volkmar, P.O. Box 207900, New Haven, CT 06520; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by grants (HD-03008 and HD-35482) from the autism and magnetic resonance divisions of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and a grant from the Autism Society of America Foundation. The authors thank “Robert Edwards” (whose name has been changed) and his family for their cooperation in the preparation of this report. Additional information (including downloadable pamphlets on the diagnosis and treatment of Asperger’s disorder) can be found at http://yale.med.info/chldstdy/autism.

|

FIGURE 1. Drawing Made by a Boy With Asperger’s Disorder, Illustrating His Interest in TimeaaDrawing illustrates the history of the universe from the moment of its creation (12:00 midnight) through geologic time, e.g., the appearance of bacteria (6:30 a.m.). It illustrates the patient’s profound interest (and knowledge) regarding this topic, which tended to be all-encompassing, as well as his less-developed fine motor abilities.

FIGURE 2. Axial T2-Weighted MRI Scana of a Boy With Asperger’s Disorder, Showing a Focal Hyperintensity (arrow) in the White Matter Under the Middle Temporal Gyrus of the Right Hemisphere, Within the Inferior Longitudinal Fasciculus

aTR=2000 msec, TE=30 msec, field of view=24 cm, matrix=256×192, number of excitations=1, 5-mm-thick slices with 2.5-mm gap.

1. Asperger H: Die “autistichen Psychopathen” im Kindersalter. Archive fur Psychiatrie und Nervenkrankheiten 1944; 117:76–136Crossref, Google Scholar

2. Kanner L: Autistic disturbances of affective contact. Nerv Child 1943; 2:217–250Medline, Google Scholar

3. Wing L: Asperger’s syndrome: a clinical account. Psychol Med 1981; 11:115–129Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Klin A, Volkmar FR: Asperger syndrome, in Handbook of Autism and Pervasive Developmental Disorders, 2nd ed. Edited by Cohen DJ, Volkmar FR. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1997, pp 94–122Google Scholar

5. Wechsler D: Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, 3rd ed. San Antonio, Tex, Psychological Corp (Harcourt), 1987Google Scholar

6. Sparrow S, Balla D, Cicchetti D: Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales. Circle Pines, Minn, American Guidance Service, 1984Google Scholar

7. Hesselink JR: White matter disease, in Clinical Magnetic Imaging, 2nd ed. Edited by Edelman R, Hesselink J, Zlatkin M. Philadelphia, WB Saunders, 1996, pp 851–879Google Scholar

8. Osborn A: Diagnostic Neuroradiology. St Louis, Mosby Year Book, 1994Google Scholar

9. Kerbeshian J, Burd L, Fisher W: Asperger’s syndrome: to be or not to be? Br J Psychiatry 1990; 156:721–725Google Scholar

10. Klin A, Volkmar FR, Sparrow SS, Cicchetti DV, Rourke BP: Validity and neuropsychological characterization of Asperger syndrome: convergence with nonverbal learning disabilities syndrome. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1995; 36:1127–1140Google Scholar

11. Szatmari P, Bartolucci G, Bremner R: Asperger’s syndrome and autism: comparison of early history and outcome. Dev Med Child Neurol 1989; 31:709–720Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Bishop DV: Autism, Asperger’s syndrome and semantic-pragmatic disorder: where are the boundaries? Br J Disord Commun 1989; 24:107–121Google Scholar

13. Ellis HD, Ellis DM, Fraser W, Deb S: A preliminary study of right hemisphere cognitive deficits and impaired social judgments among young people with Asperger syndrome. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1994; 3:255–266Crossref, Google Scholar

14. Rourke BP: Nonverbal Learning Disabilities: The Syndrome and the Model. New York, Guilford, 1989Google Scholar

15. Ghaziuddin M, Tsai LY, Ghaziuddin N: Brief report: a comparison of the diagnostic criteria for Asperger syndrome. J Autism Dev Disord 1992; 22:643–649Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Miller JN, Ozonoff S: Did Asperger’s cases have Asperger disorder? a research note. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1997; 38:247–251Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Volkmar FR, Klin A, Siegel B, Szatmari P, Lord C, Campbell M, Freeman BJ, Cicchetti DV, Rutter M, Kline W, Buitelaar J, Hattab Y, Fombonne E, Fuentes J, Werry J, Stone W, Kerbeshian J, Hoshino Y, Bregman J, Loveland K, Szymanski L, Towbin K: Field trial for autistic disorder in DSM-IV. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:1361–1367Google Scholar

18. Lincoln A, Courchesne E, Allen M, Hanson E, Ene M: Neurobiology of Asperger syndrome: seven case studies and quantitative magnetic resonance imaging findings, in Asperger Syndrome or High Functioning Autism? Edited by Schopler E, Mesibov GB, Kunc LJ. New York, Plenum, 1998, pp 145–166Google Scholar

19. Ozonoff S, Rogers SJ, Pennington BF: Asperger’s syndrome: evidence of an empirical distinction from high-functioning autism. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1991; 32:1107–1122Google Scholar

20. Volkmar FR, Klin A, Pauls D: Nosological and genetic aspects of Asperger syndrome. J Autism Dev Disord 1998; 28:457–463Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Ghaziuddin M, Weidmer-Mikhail E, Ghaziuddin N: Comorbidity of Asperger syndrome: a preliminary report. J Intellect Disabil Res 1998; 42(part 4):279–283Google Scholar

22. Sparrow S: Developmentally based assessments, in Handbook of Autism and Pervasive Developmental Disorder, 2nd ed. Edited by Cohen DJ, Volkmar FR. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1997, pp 411–447Google Scholar

23. Makris N, Meyer JW, Bates JF, Yeterian EH, Kennedy DN, Caviness VS: MRI-based topographic parcellation of human cerebral white matter and nuclei, II: rationale and applications with systematics of cerebral connectivity. Neuroimage 1999; 9:18–45Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Puce A, Allison T, Bentin S, Gore JC, McCarthy G: Temporal cortex activation in humans viewing eye and mouth movements. J Neurosci 1998; 18:2188–2199Google Scholar

25. Schultz RT, Gauthier I, Fulbright R, Anderson AW, Lacadie C, Skudlarski P, Tarr MJ, Cohen DJ, Gore JC: Are face identity and emotion processed automatically? Abstracts of the Third International Conference on Functional Mapping of the Human Brain, Copenhagen, Denmark, May 17–22, 1997. Neuroimage 1997; 5(suppl 4):S148Google Scholar

26. Saunders RC, Kolachana BS, Bachevalier J, Weinberger DR: Neonatal lesions of the medial temporal lobe disrupt prefrontal cortical regulation of striatal dopamine. Nature 1998; 393:169–171Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Klin A, Volkmar FR: Treatment and intervention guidelines for individuals with Asperger syndrome, in Asperger Syndrome. Edited by Klin A, Sparrow SS, Volkmar FR. New York, Guilford, 2000Google Scholar

28. Schultz RT, Romanski L, Tsatsanis K: Neurofunctional models of autism and Asperger syndrome: clues from neuroimaging. Ibid.Google Scholar