Risk-Taking Behaviors Among Israeli Adolescents Exposed to Recurrent Terrorism: Provoking Danger Under Continuous Threat?

Abstract

Objective: This study aimed to assess 1) the relationship between risk-taking behaviors and exposure to terrorism, 2) the relationship between posttraumatic symptoms and risk-taking behaviors, and 3) gender differences in the type and frequency of risk-taking behaviors and their differential associations with posttraumatic symptoms. Method: The participants were 409 Israeli adolescents 15 to 18 years of age. Exposure to terrorism was assessed with a questionnaire developed specifically for the Israeli security situation. Posttraumatic symptoms were measured with the University of California at Los Angeles Reaction Index. Functional impairment was measured with the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children. Risk-taking behavior—and the adolescents’ perceptions of such behavior—was assessed with a self-report questionnaire. Results: Israeli adolescents exposed to continuous threats of terrorist attacks reported high levels of risk-taking behaviors. The severity of risk-taking was associated with greater terrorism exposure. Adolescents suffering from posttraumatic symptoms reported more risk-taking behaviors than nonsymptomatic adolescents. Although there was no gender difference in the degree of exposure to terrorism, boys reported taking more risks than girls. The association between posttraumatic symptoms and risk-taking behaviors was stronger in boys than girls. Functional impairment, gender, avoidance symptoms, level of exposure, and degree of fear predicted the severity of risk-taking behaviors. Conclusions: Clinicians and educators should be aware of the strong link between posttraumatic distress and risk-taking behaviors. Risk-taking behaviors may be a manifestation of functional impairment and posttraumatic distress, especially for boys exposed to terrorism.

Risk-taking behavior is defined as volitional behavior whose outcome is uncertain and which entails negative consequences (1) . More than any other age group, adolescents are prone to engaging in risk-taking behaviors, such as dangerous driving, drug and alcohol use, unprotected sex, delinquency, and eating disorders (2 , 3) . Several theories and models have been proposed to explain the prevalence of such behaviors during adolescence (4) .

Developmental perspectives view risk-taking as an aspect of proneness to problem behavior and a maladaptive trait (5) . But risk-taking behavior can also be seen as functional and goal-directed behavior that can play an important part in the developmental tasks of adolescence (6) . Biologically-based theories attribute adolescent risk-taking to hormonal changes and genetic dispositions (7) and tendencies to seek sensation (8) . Cognitive perspectives emphasize cognitive processes, such as decision-making, perceptions of gains and losses (9) , expectations about the future (10) , and biases in risk perception (11) . Social and environmental theories focus on the influence of parents, teachers, and peers, as well as the effects of communities and culture (4) . These environmental factors may lead to stress and thus affect people’s cognitive processes and behaviors (10) .

Several studies have shown a direct link between exposure to trauma and different types of risk-taking behavior among adolescents. Young people exposed to the Buffalo Creek disaster in the U.S. reported an increase in risk-taking behaviors, such as alcohol use, smoking, car racing, violence, and higher rates of delinquency and teen pregnancies (12) . Similarly, adolescents exposed to community violence reported increased drug and alcohol use, delinquency and weapon-carrying (13 , 14) , substance abuse, and HIV-risk behaviors (15 , 16) . Increased alcohol use and violent behavior were also found in a longitudinal study of adolescents exposed to a fire disaster in the Netherlands (17) . Similarly, Israeli adolescents show a strong association between exposure to ongoing terrorism and alcohol consumption (18) .

The association between exposure to traumatic events and risk-taking behaviors is attributed by Glodich (14) to the tendency for behavioral reenactment, which is described as a repetition of actions, taken or imagined, during moments of the traumatic events (19) . That is, risk-taking behavior is conceptualized as a way of remembering or as an unconscious attempt to gain mastery over the trauma (14 , 20) .

Virtually all studies of the psychological effects of trauma indicate that women and girls are more inclined to report anxiety and mood symptoms (21) and are at a higher risk for developing posttraumatic distress than men and boys (22) . However, boys tend to manifest more disruption in their behavioral adaptation (21) . That is, boys tend to express psychological disturbances through acting out and external behavior (22) , whereas girls tend to express their distress by turning their feelings inward, leading to depression or anxiety (23) . These results are consistent with boys’ greater tendency for risk-taking behaviors compared to girls (24) .

However, little is known about maladaptive coping and the risk-taking behaviors that adolescents may exhibit in the face of recurrent exposure to terrorist attacks. The recurrent experience of terrorist attacks is often described as being in a continuous state of siege in which attacks meld one into the next. Furthermore, the differential impact of this situation on risk-taking behaviors in boys and girls needs to be further clarified. We therefore investigated 1) whether risk-taking behaviors are associated with the degree of adolescents’ exposure to terrorism 2), whether higher levels of posttraumatic symptoms are associated with more risk-taking behaviors, and 3) whether there are gender differences in the type and frequency of risk-taking behaviors.

Method

Participants

The participants were 409 adolescents between 15 and 18 years of age (mean=16.44, SD=0.65) who were drawn from nine classes that were randomly sampled from five different Israeli high schools (two in Jerusalem and three in Haifa, two major cities that were exposed to numerous terrorist attacks). The sample comprised 192 (46.9%) boys and 217 (53.1%) girls. All students who were present in these classes the day the questionnaire was administered participated in the study.

Measures

Demographic Characteristics

The participants reported their age, gender, and grade level.

Terrorism Exposure Measurement

The participants were asked to respond “yes” or “no” to eight statements about their experiences during the previous 3 years, since the outbreak of the Al-Aqsa intifada in September 2000:

“I was present at the site of a terrorist attack and hurt.”

“I was present at the site of a terrorist attack but not hurt.”

“Someone close to me was killed in a terrorist attack.”

“Someone close to me was wounded in a terrorist attack.”

“I was near a terrorist attack.”

“I was at the location of a terrorist attack immediately before or after the attack.”

“I was supposed to be in the area in which a terrorist attack happened.”

“I was not involved in a terrorist attack.” (measure available from the first author)

Exposure level was defined as a three-level variable:

Personal exposure: having been present at a terrorist attack with or without being physically injured or knowing someone close who was injured or killed in such an attack.

Near miss: having been near the site of a terrorist attack, having been there before or after an attack, or having planned to be at the site of an attack.

No exposure: no exposure to a terrorist attack, excluding exposure through the media.

If a student reported more than one type of terrorist exposure, he or she was categorized in the more severe category. In view of our interest in the experience of ongoing exposure to terrorism, the respondents were not asked to specify the exact date and time of each occurrence of exposure.

To assess the A1 criterion of posttraumatic stress symptoms (the objective exposure to a traumatic event), we incorporated items derived from DSM-IV criteria (25) , previously used by Chemtob et al. (26) : respondents were asked to indicate (in a yes or no answer) whether exposure to terrorism had resulted in the sense that they might die or be physically injured or that someone in their family might be killed or physically injured. In addition, we asked whether they had felt that a best friend or boyfriend or girlfriend might be killed or physically injured. The item referring to best friend or significant other was added to reflect the developmental concerns of adolescents. Endorsement of at least one of the items was regarded as meeting criterion A1. To assess criterion A2 (subjective response to a traumatic event), the respondents were asked to rate the subjective level of fear, helplessness, and horror they felt in connection with exposure to terrorism on a 5-point scale. Endorsement of at least one item at level 4 or 5 was necessary to meet criterion A2.

University of California at Los Angeles PTSD Index

The adolescent version of the University of California at Los Angeles Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) scale (unpublished scale by Rodriguez et al.) comprises 20 self-report items derived from DSM-IV PTSD symptom criteria. Respondents indicate how frequently they experienced a symptom during the last 4 weeks with a 5-point Likert scale ranging from none (0) to very often (4). The original English version of this scale reported a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.90, and its test-retest reliability has ranged from good to excellent (27) . The questionnaire was translated into Hebrew, cross-translated, and adapted to the Israeli situation in a pilot study (available from the first author). The internal consistency of the Israeli version of the PTSD Child Reaction Index was highly satisfactory (Cronbach’s alpha=0.89). A PTSD severity score was computed by summing the scores on each of the 20 items. In addition, scores were calculated for the sum of intrusive symptoms (criterion B), the sum of avoidance symptoms (criterion C), and the sum of hyperarousal symptoms (criterion D). Self-reported symptoms were classified as full PTSD when all criteria required for a DSM-IV diagnosis were met (A1=exposure, A2=subjective fear [symptoms endorsed at the level of severe and very severe], B=reexperiencing [at least one symptom], C=avoidance [at least three symptoms], D=increased arousal [at least two symptoms], and F=functional impairment [as measured by the Functional Impairment Questionnaire]). For criteria B, C, and D, symptoms were counted when endorsed as “some of the time,” “much of the time,” or “most of the time” (unpublished scale by Rodriguez et al.). Partial PTSD was defined as meeting criteria A1, A2, F, and two of criteria B, C, and D.

Functional Impairment Questionnaire

Functional impairment was measured by using items that are relevant according to DSM-IV that were drawn from the Diagnostic Predictive Scales and derived from the Child Diagnostic Interview Schedule (28) . The participants were asked to indicate on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much) whether they had experienced functional impairment specifically tied to terrorism in their social relationships, their school performance, their family relationships, or their after-school activities during the last 4 weeks. A total functional impairment score was computed as the sum of all items. The internal reliability of the Functional Impairment Questionnaire was highly satisfactory (Cronbach’s alpha=0.87). To meet the functional impairment criterion (F) for PTSD, a respondent was required to have reported “much” or “very much” impairment in at least one domain, reflecting clinically significant impairment.

Risk-Taking Behavior

The participants were asked to rate how often they engaged in each of 16 risk-taking behaviors (e.g., drinking alcohol, hitchhiking, having unprotected sex; see Table 1 for a full list) during the last 4 weeks on a Likert scale from 0 (never) to 4 (every day) (measure available from the first author). Based on previous findings that risk-taking behaviors often covary (4), a total score was calculated as the sum of all items to reflect the severity level of all of the risk-taking behaviors. The frequency of risk-taking behaviors was calculated by using a cutoff score above 0 (i.e., the risk-taking behavior occurred at least once). The inter-item reliability (Cronbach’s alpha) of the risk-taking behavior questionnaire was 0.86.

Procedure

The screening questionnaires were approved by the Research Oversight Committee of the Israel Ministry of Education. The school principal sent information about the screening procedure and consent forms to parents. The parents could opt out of screening, as could the students. The self-report questionnaires were administered by the homeroom teacher and took about 45 minutes to complete. Research staff was available to present the purpose of the screening and to answer questions afterward. Students were also given a contact telephone number in case any concerns or questions arose. To protect confidentiality, the questionnaires were administered and analyzed with a coded system. The identification codes for students who met PTSD criteria were given to school counselors, who then interviewed the adolescents to confirm the self-reported symptoms and functional impairment and to inform their parents that counseling might be warranted. The reported risk-taking behaviors were also aggregated for the entire class and reported to the school counselors and teachers. The teachers were trained and supervised in delivering a special class on prevention of risk-taking behaviors, highlighting the possible association between traumatic experiences and taking risks.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive analyses examined the frequencies of risk-taking behaviors, full PTSD, and partial PTSD among the total sample. We used chi-square tests with Bonferroni corrections to explore gender differences in risk-taking behaviors and differences between symptomatic and nonsymptomatic adolescents in such behaviors. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Scheffé post hoc comparisons, was performed to explore the differences in risk-taking behaviors among the three exposure levels. A Pearson’s correlation was calculated to evaluate the relation between risk-taking behavior and posttraumatic symptoms. We used multiple regression with dummy variables to test for gender differences in the association between risk-taking behaviors and posttraumatic symptoms and hierarchical regression to identify predictors of risk-taking behaviors.

Results

Risk-Taking Behaviors in the Sample

The frequencies of risk-taking behaviors among boys and girls are listed in Table 1 . Although the most frequently reported behaviors were disobedience in school (68.5%) and disobeying parents (64.1%), there were high percentages of potentially life-threatening behaviors, such as dangerous driving (18.1%), carrying weapons (14.2%), and participating in Russian roulette-like games (8.6%).

Boys reported more risk-taking behaviors than girls: fighting, dangerous driving, having unprotected sex, drinking alcohol, hitchhiking, playing Russian roulette, disobeying school authorities, breaking the law, and carrying weapons. Dysfunctional eating was more prevalent in girls than boys. Other behaviors, such as using drugs, smoking cigarettes, stealing, disobeying parents, running away from home, and injuring self, did not differ between boys and girls ( Table 1 ).

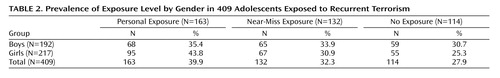

Risk-Taking Behaviors and Exposure to Terrorism

No significant differences between boys and girls were found in level of exposure to recurrent terrorism (χ 2 =3.13, df=2, p<0.21) ( Table 2 ). A two-way ANOVA with Scheffé post hoc comparisons was conducted, with severity of risk-taking behaviors as the dependent variable and gender and exposure level as independent variables. No interaction was found between exposure and gender in severity of risk-taking behaviors (F=0.46, df=1, 408, p<0.63). A main effect for gender was found (F=5.32, df=2, 408, p=0.005), indicating greater severity of risk-taking behaviors among boys compared to girls. A main effect of exposure was found (F=7.93, df=2, 408, p<0.001), and Scheffé post hoc comparisons were conducted, indicating that there was a greater severity of risk-taking behaviors among the personal exposure group compared to the group with no exposure (for means and SDs, see Table 3 ).

Risk-Taking Behaviors and Posttraumatic Symptoms

Twenty adolescents, 4.9% of the sample, met PTSD criteria (available from the first author), whereas another 34 (8.3%) met the criteria for partial PTSD. Chi-square analyses tested differences in risk-taking behavior between the symptomatic group (full or partial PTSD) and the nonsymptomatic group. Adolescents who met the PTSD or partial PTSD criteria reported more risk-taking behaviors than nonsymptomatic youth ( Table 4 ). Significant differences were found in smoking cigarettes, stealing, eating dysfunctionally, running away from home, and injuring the self. No significant differences were found in fighting, using drugs, driving dangerously, having unprotected sex, drinking alcohol, hitchhiking, playing Russian roulette, disobeying parents, disobeying school authorities, carrying weapons, and breaking the law.

There was a significant positive correlation (r=0.34, p<0.001) between risk-taking behaviors and the severity of posttraumatic symptoms. A significant correlation was also found between the severity of risk-taking behavior and the severity of each of the posttraumatic symptom clusters: reexperiencing (r=0.25, p<0.001), avoidance (r=0.39, p<0.001), and hyperarousal (r=0.20, p<0.0001).

Gender Differences

A multiple regression using dummy variables, with posttraumatic symptoms, gender, and the interaction between them as predictors of risk-taking behaviors, revealed a significant gender interaction (β=0.398, p<0.001), indicating a higher correlation between posttraumatic symptoms and risk-taking behaviors among boys than girls (r=0.44, p<0.001, versus r=0.29, p<0.001); see Figure 1 .

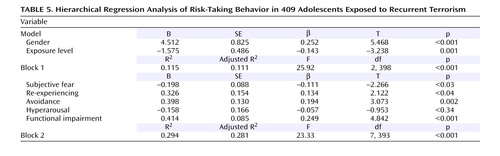

Predictors of Risk-Taking Behaviors

We conducted hierarchical regression analysis, with risk-taking behavior as the dependent variable; the first block entered in the model included gender and exposure to terrorism, explaining 11.5% of the variance. Both gender (β=0.252, p<0.001) and exposure to terrorism (β= –0.143, p=0.001) were found to be significant predictors of risk-taking behaviors. The second block entered in the model included all posttraumatic symptoms (subjective fear, reexperiencing, avoidance, hyperarousal) and functional impairment, and it explained 17.7% of the variance. All of the variables, excluding hyperarousal, were found to be significant predictors of risk-taking behaviors: subjective fear (β=–0.111, p<0.03), reexperiencing (β=0.134, p<0.04), avoidance (β=0.194, p=0.002), and functional impairment (β=0.249, p<0.001). The total variance explained by both blocks in the model was 29.4% ( Table 5 ).

Discussion

Our results indicate an alarming rate of self-reported risk-taking behaviors by Israeli adolescents living under the continuous threat of terrorism. Youngsters reporting personal exposure to terrorism reported more risk-taking behaviors than adolescents with no such exposure. Posttraumatic symptoms were also positively associated with risk-taking behaviors. Indeed, posttraumatic symptoms, including fear, reexperiencing, avoidance, and functional impairment, were found to be significant predictors of the severity of risk-taking behaviors beyond gender and level of exposure.

Our finding of an association between exposure to the continuous threat of terrorism and risk-taking behaviors among Israeli adolescents is consistent with a recent Israeli finding that adolescents knowing someone hurt in terrorist attacks are more likely to consume alcohol (18) . Similarly, data from a study in Manhattan 5 to 8 weeks after the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, showed an increase in the rates of cigarette smoking and alcohol and substance abuse (29) . Moreover, our findings show that in addition to exposure to terrorism and loss, posttraumatic distress is strongly associated with risk-taking behaviors. In fact, Israeli youngsters who reported symptoms meeting PTSD criteria show a significantly higher rate of risk-taking behaviors, with an increase in 10 of the 16 identified behaviors, than nonsymptomatic youth.

Developmental theories assert that risk-taking behavior during adolescence is developmentally normal and even important (7) . Furthermore, sensation-seeking and egocentrism, which are part of adolescent development, are commonly associated with risk-taking behaviors (30) . According to Rolison and Scherman (7) , risk-taking is a way of coping with the physical and environmental changes that adolescents undergo. The situation of ongoing terrorism in Israel for the last 4 years involves constant instability, uncertainty, and threat. Anyone can become a victim by being in the wrong place at the wrong time. This situation amplifies the identity dilemmas and other issues that the adolescents are already struggling with. Risk-taking behavior can thus be seen as a maladaptive endeavor by an adolescent to regain control and mastery.

Although there were no gender differences in the level of exposure to terrorism, boys were more likely to report risk-taking behaviors, with the exception of dysfunctional eating. In contrast, girls reported more symptoms of emotional distress. Greater functional impairment in boys and greater emotional distress among girls were also found in adolescents exposed to terrorism in Jerusalem (31) . This greater behavioral manifestation of terrorism-related distress among boys than girls appears to be a consistent pattern, as it was also found by Collishaw et al. (32) in their review of 25 years of research on adolescents.

There are a number of possible explanations for this gender difference. Clearly, certain behaviors may be seen as inherently more likely to be engaged in by male adolescents, for example, carrying weapons. Hirschberger et al. (24) suggested that risk is a central component of the masculine world view. Because a world view buffers against existential anxieties, risk-taking behavior may protect boys from the anxiety associated with their awareness of their mortality. This may explain why boys tend to engage in more risk-taking behaviors than girls when they live with ongoing terrorism and confront the trauma of arbitrary death and loss that threatens self-esteem and leads to helplessness, anxiety, and shame. However, in spite of these gender differences, the fairly high rate of self-reported risk-taking behavior we found among adolescent Israeli girls is striking. We propose that the importance of the gender difference may pertain to the apparent greater likelihood of boys to express posttraumatic effects through increased risk-taking in contrast to girls’ greater reports of symptom-related distress. In short, boys may be more likely to use behavioral risk-taking as a means of mastering terrorism-related distress than girls.

Risk-Taking Behavior and Functional Impairment

The degree of functional impairment serves as one indicator of PTSD severity; indeed, this is a bedrock concept in DSM-IV-TR. It is through the behavioral manifestations of functional impairment that a psychiatric disorder impinges on a person’s ability to achieve basic goals (33) . Most researchers concerned with functional impairment in adolescents focus primarily on school and social performance as the domains of function. They do not fully consider aspects of self-care (including maintaining safety) as a domain for the assessment of functional impairment. The significant findings of this study, indicating a high correlation between risk-taking behaviors and posttraumatic symptoms, as well as between risk-taking behaviors and functional impairment, suggest that risk-taking behaviors should be considered an additional domain of functional impairment to be investigated in future research on terror-related trauma and, more generally, on PTSD. In particular, Chemtob and Taylor (34) have proposed that risk-taking behaviors be conceptualized on a continuum of self-care functioning, ranging from self-protective behaviors to potentially self-injurious acts culminating in suicide.

Symptoms belonging to the avoidance cluster predicted risk-taking behaviors here better than those in the other two clusters. Risk-taking behavior can function in the same way as avoidance and constriction of trauma-related emotional and cognitive reactions, externalizing posttraumatic distress and helping adolescents relieve tension and distract themselves from problems and conflicts in a variety of life areas (9) . North et al. (35) claimed that avoidance and numbing symptoms are highly specific for the diagnosis of PTSD and are also associated with reports of functional impairment. Therefore, risk-taking behavior, conceptualized as a potential manifestation of the cluster of avoidance, can be indicative of PTSD in youth.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, it is based on self-report data without corroboration from additional sources or observations of actual behavior. Second, the absence of data regarding previous traumas makes it impossible to rule out a link between the reported risk-taking behaviors and trauma not related to terrorism. Third, the current study was based on a convenience sample that may not permit generalization of the findings to the entire area. Fourth, because of its cross-sectional and correlational nature, the study could not eliminate alternative interpretations of these associations.

Clinical Implications

The increase in risk-taking behavior associated with exposure to terrorism and with PTSD symptoms has important implications for clinicians and educators. Clinicians who intervene with adolescents suffering from terrorism-related PTSD do not routinely assess them for risk-taking behavior. Our data suggest that clinicians should be aware that the potential for self-injury among young people suffering from PTSD includes self-injurious behaviors apart from suicide. Consequently, clinicians should actively assess the adolescents for the type and frequency of risk-taking behaviors and explicitly include such manifestations of PTSD in their treatment plans. Conversely, during periods of ongoing terrorism, educators who come in contact with adolescents engaging in risk-taking behaviors in school, including systematic defiance of authority, should consider the possibility that such behaviors are a manifestation of terrorism-related exposure and distress.

Future research should explore the associations among trauma and risk-taking behavior with respect to other possible predictors, including depression, socioeconomic factors, or high-risk groups, such as immigrants, minorities, and younger children, that may function as mediating factors between PTSD and risk-taking behavior. Additionally, research should explore gender-related associations between posttraumatic symptoms with respect to the risk-taking behaviors that were equally reported by both genders. Finally, laboratory research oriented toward identifying the mechanisms by which exposure to trauma may increase risk-taking behavior would help elucidate the findings reported here.

1. Irwin CE: The theoretical concept of at-risk adolescents. Adolesc Med: State of the Art Rev 1990; 1:1–14Google Scholar

2. Arnett JJ: Risk behavior and family role transitions during the twenties. J Youth Adolesc 1998; 27:301–320Google Scholar

3. Muss RE, Porton HD: Interesting risk-behavior among adolescents, in Adolescent Behavior and Society. Edited by Muss RE, Porton HD. Boston, McGraw-Hill, 1998, pp 422–431Google Scholar

4. Igra V, Irwin CE: Theories of adolescents risk taking behavior, in Handbook of Adolescent Health Risk Behavior. Edited by Diclement RJ, Hansen WB, Ponton LE. New York, Plenum, 1996Google Scholar

5. Jessor R, Jessor SL: Problem Behavior and Psychological Development: A Longitudinal Study of Stress. New York, Academic Press, 1977Google Scholar

6. Jessor R: Risk-behavior in adolescence: a psychosocial framework for understanding and action. J Adolesc Health 1991; 12:597–605Google Scholar

7. Rolison M, Scherman A: Factors influencing adolescents’ decisions to engage in risk-taking behavior. Adolescence 2002; 37:585–597Google Scholar

8. Hansen EB, Breivik G: Sensation-seeking as a predictor of positive and negative risk behavior among adolescents. Pers Individ Diff 2001; 30:627–640Google Scholar

9. Ben-Zur H, Reshef-Kfir Y: Risk taking and coping strategies among Israeli adolescents. J Adolesc 2003; 26:255–265Google Scholar

10. Harris KM, Duncan GJ, Boisjoly J: Evaluating the role of the “nothing to lose” attitudes on risky behavior in adolescence. Soc Forces 2002; 80:1005–1039Google Scholar

11. Weinstein ND: Unrealistic optimism about future life events. J Pers Soc Psychol 1980; 39:806–820Google Scholar

12. Sugar M: Severe physical trauma in adolescence, in Trauma and Adolescence. Edited by Sugar M. Madison, Conn, International Universities Press, 1999, pp 183–201Google Scholar

13. Glodich A, Allen JG: Adolescents exposed to violence and abuse: a review of the group therapy literature with an emphasis on preventing trauma reenactment. J Child Adolesc Group Ther 1998; 8:135–154Google Scholar

14. Glodich A: Traumatic exposure to violence: a comprehensive review of the child and adolescent literature. Smith Coll Stud Soc Work 1998; 68:321–345Google Scholar

15. Steven SJ, Murphy BS, McKnight K: Traumatic stress and gender differences in relationship to substance abuse, mental health, physical health and HIV risk-taking in a sample of adolescents enrolled in drug treatment. J Am Professional Soc on the Abuse of Child 2003; 8:46–57Google Scholar

16. Gore-Feltun C, Koopman C: Traumatic stress experience: harbinger of risk-behavior among HIV-positive adults. J Trauma Dissociation 2002; 3:121–135Google Scholar

17. Reijeneveld SA, Crone MR, Verhulst FC, Verloove-Vanhorrick SP: The effects of a severe disaster on the mental health of adolescents: a controlled study. Lancet 2003; 362:691–696Google Scholar

18. Schiff M, Benbenishty R, McKay M, DeVoe E, Liu X, Hasin D: Exposure to terrorism and Israeli youth’s psychological distress and alcohol use: an exploratory study. Am J Addict 2006; 15:220–226Google Scholar

19. Pynoos RS, Nader K: Psychological first aid and treatment approach to children exposed to community violence: research implications. J Trauma Stress 1988; 1:445–473Google Scholar

20. Van der Kolk BA: The psychological processing of traumatic experience: Rorschach patterns in PTSD. J Trauma Stress 1989; 2:259–274Google Scholar

21. Shaw JA: Children exposed to war/terrorism. Clinic Child Fam Psychiatry Rev 2003; 6:237–246Google Scholar

22. Davis L, Siegel LJ: Post traumatic stress disorder in children and adolescents: a review and analysis. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 2000; 3:135–154Google Scholar

23. Ostrov E, Offer D, Howard KI: Gender differences in adolescent symptomatology: a normative study: J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1989; 28:394–398Google Scholar

24. Hirschberger G, Florian V, Mikulinser M, Goldenberg JL, Pyszczynski T: Gender differences in the willingness to engage in risky behavior: a terror management perspective. Death Stud 2002; 26:117–141Google Scholar

25. American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, IV-TR. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 2000Google Scholar

26. Chemtob CM, Nakashima J, Hamada RS: Psychosocial intervention for post disaster trauma symptoms in elementary school children. Arch Pediatric Adolesc Med 2002; 156:211–216Google Scholar

27. Steinberg AM, Brymer MJ, Decker KB, Pynoos RS: The University of California at Los Angeles Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Reaction Index. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2004; 6:96–100Google Scholar

28. Lucas CP, Zhang H, Fisher PW, Shaffer D, Regier DA, Narrow WE, Bourdon K, Dulcan MK, Canino G, Rubio-Stipec M, Lahey BB, Friman P: The DISC Predictive Scales (DPS): efficiently screening for diagnoses. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2001; 40:443–449Google Scholar

29. Vlahov D, Galea S, Resnick H, Ahern J, Boscarino J, Bucuvalas M, Gold J, Kilpatrick D: Increased use of cigarettes, alcohol, and marijuana among Manhattan, N.Y., residents after the Sept 11th terrorist attacks. Am J Epidemiol 2002; 155:988–996Google Scholar

30. Arnett JJ: Reckless behavior in adolescence: a developmental perspective. Develop Rev 1992; 12:339–373Google Scholar

31. Pat-Horenczyk R: Post-traumatic distress in adolescents exposed to ongoing terror: findings from a school-based screening project in the Jerusalem area, in The Trauma of Terrorism: Sharing Knowledge and Shared Care. Edited by Danieli Y, Brom D, Sills J. New York, Haworth Press, 2005, pp 335–347Google Scholar

32. Collishaw S, Maughan B, Goodman R, Pickels A: Time trends in adolescent mental health. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2004; 45:1350–1362Google Scholar

33. Spitalny K: Clinical findings regarding PTSD in children and adolescents, in Post Traumatic Stress Disorder in Children and Adolescents. Edited by Silva RR. New York, Norton, 2004, pp 141–162Google Scholar

34. Chemtob CM, Taylor TL: The Treatment of Traumatized Children in Treating Trauma Survivors With PTSD. Edited by Yehuda R. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 2002, pp 75–126Google Scholar

35. North CS, Nixon SJ, Shariat S, Malloneed S, McMillen JC, Spitznagel E, Smith E: Psychiatric disorders among survivors of the Oklahoma City bombing. JAMA 1999; 282:755–762Google Scholar