A Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial of Oxcarbazepine in the Treatment of Bipolar Disorder in Children and Adolescents

Abstract

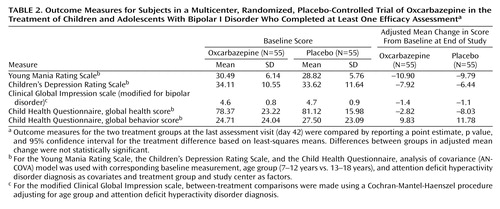

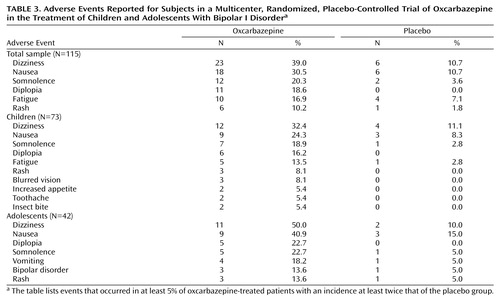

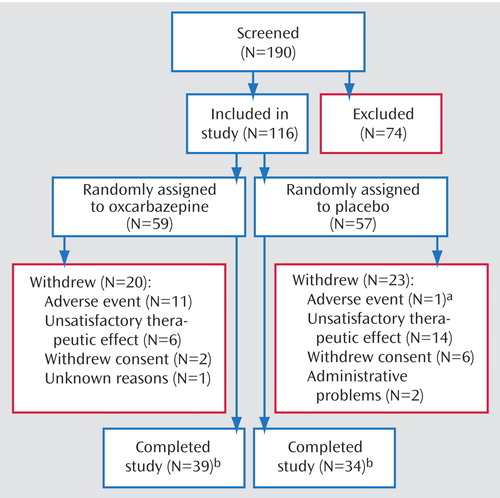

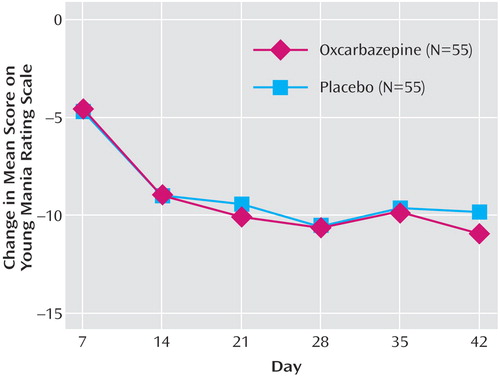

Objective: This multicenter trial examined the efficacy and safety of oxcarbazepine in the treatment of bipolar disorder in children and adolescents. Method: A total of 116 outpatients 7 to 18 years of age with bipolar I disorder, manic or mixed, were recruited at 20 centers in the United States and randomly assigned to receive 7 weeks of double-blinded, flexibly dosed treatment with oxcarbazepine (maximum dose 900–2400 mg/day) or placebo. The primary efficacy measure was the mean change from baseline to endpoint in the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS), using the last-observation-carried-forward method. Results: Oxcarbazepine (mean dose=1515 mg/day) did not significantly improve YMRS scores at endpoint compared with placebo [adjusted mean change: oxcarbazepine, –10.90 (N=55); placebo, –9.79 (N=55)]. Dizziness, nausea, somnolence, diplopia, fatigue, and rash were each reported in at least 5% of the patients in the oxcarbazepine group with an incidence at least twice that of the placebo group. The majority of adverse events were mild to moderate and occurred during the titration period. Eleven patients (19%) in the oxcarbazepine group discontinued the study because of adverse events, compared with two (4%) in the placebo group. Conclusions: Oxcarbazepine is not significantly superior to placebo in the treatment of bipolar disorder in youths. While the overall adverse event profile was similar to that reported for patients with epilepsy, the incidence of psychiatric adverse events for both the oxcarbazepine and placebo groups was higher than that reported for the epilepsy population.

Bipolar disorder is a serious illness in children and adolescents. Clinical characteristics often include mixed episodes of mania/hypomania, grandiose delusions, and suicidality (1) . The illness has a long duration and tends to be chronic in children and adolescents. In a 4-year prospective longitudinal study of 86 youths with bipolar disorder, the relapse rate was 64% (2) . Young age at onset has been associated with greater rates of substance abuse, comorbid anxiety disorders, suicide attempts, and violence as well as more recurrences and shorter periods of euthymia in adulthood (3 , 4) .

Given the severity of bipolar disorder in children and adolescents and the adverse effects it has on social, family, and academic functioning, it is essential to identify effective treatments for this illness. A recently published treatment guideline for bipolar disorder in children and adolescents acknowledged the paucity of controlled medication trials for youths to guide treatment decisions (5) . Although anticonvulsants, lithium, and atypical antipsychotics are frequently used to treat this disorder in children (6) , no studies have been published of large-scale, multicenter, randomized, controlled trials with youths who have bipolar disorder. A pilot controlled trial of topiramate for the treatment of mania in youths with bipolar disorder showed no significant difference between topiramate and placebo on the primary outcome measure (7) . Recently olanzapine was reported to show superiority to placebo in the treatment of bipolar disorder in adolescents (8) .

Oxcarbazepine, a 10-keto analogue of carbamazepine, is approved for both monotherapy and combination therapy for partial seizures in adults as well as in children at least 4 years of age in the United States and 6 years of age in the European Union (9) . Oxcarbazepine does not appear to induce its own metabolism, and it is not highly protein bound (10) . A review of data from small randomized, controlled studies, open studies, and retrospective chart reviews showed that oxcarbazepine is efficacious for the treatment of acute mania in adults (11) . Four small (ranging from six to 52 subjects) randomized, controlled trials of oxcarbazepine for the treatment of adults with mania have been conducted. These studies suggested that oxcarbazepine is superior to placebo (12) and has an efficacy comparable to that of valproate (13 , 14) , lithium (15) , and haloperidol (15 , 16) . There have been three case reports of youths with bipolar disorder who had a positive response to treatment with oxcarbazepine (17 , 18) .

In this article, we report the first multicenter, double-blind, randomized, controlled clinical trial for the treatment of bipolar disorder in children and adolescents. This study was designed to examine the efficacy and safety of oxcarbazepine for the treatment of bipolar disorder in children and adolescents.

METHOD

Subjects

Patients were recruited from 20 centers in the United States. The study was conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the Declaration of Helsinki (1996). The protocol and statement of informed consent were approved by the institutional review board at each center before the study was initiated. Written informed consent was obtained from each study subject’s parent or legal guardian, as was consent or assent from the study subject prior to participation in the study.

To be eligible for the study, subjects had to be outpatients 7 to 18 years of age and have a diagnosis of bipolar I disorder, manic or mixed episode, as defined in DSM-IV and confirmed by the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children—Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL) (19) . A total score of 20 or above on the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) (20) was required at the baseline visit; patients who did not qualify could repeat the measure within 3 days.

Exclusion criteria included a current primary DSM-IV axis I diagnosis of schizophrenia, delirium, anorexia nervosa, autism, bulimia, or substance-induced mood disorder; a need for inpatient or partial psychiatric hospitalization among psychotic patients and patients experiencing an extreme manic episode; a history of seizure disorders; an IQ below 70; or a history of psychogenic polydipsia. Patients whom the investigator judged to be at risk of suicide or homicide and patients who were acutely suicidal or homicidal at the time of screening were excluded. Female patients of childbearing potential who had a positive serum pregnancy test, were not practicing reliable contraception, or were nursing were excluded. Other exclusion criteria included a history of symptomatic hyponatremia or serum sodium levels <135 meq/liter, current treatment with oxcarbazepine, or a previous failure to respond to oxcarbazepine. Patients who were taking or planning to take other investigational drugs during the study period or within 1 month before entering the study, who were receiving antimanic medications that could not be tapered, or who had a known hypersensitivity to oxcarbazepine or carbamazepine were also excluded from the study. Patients were required to be free of psychotropic medications, with the exception of stimulants and diphenhydramine, before entering the study. For patients taking fluoxetine or other medications with a long half-life, a washout period based on the half-life of the medication was required before participation in the study. Patients with comorbid attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) were permitted to continue treatment with a stimulant during the course of the trial if they had been on a stable dose of the stimulant for at least 3 months before participating in the trial. Diphenhydramine was permitted for the control of agitation and aggression, starting at 0.5 mg/kg of body weight or 25 mg per dose, to a maximum of 100 mg/day. However, diphenhydramine was to be avoided for at least 8 hours prior to the administration of any efficacy assessments.

Study Design

This was a prospective, multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of oxcarbazepine as monotherapy in the outpatient treatment of children and adolescents with a diagnosis of bipolar I disorder. The study consisted of a 3- to 14-day baseline phase and a 7-week double-blind phase. The double-blind phase consisted of three periods: a 2-week titration period, a 4-week maintenance period, and a 1-week down-titration period. During the baseline phase, patients underwent the following assessments for eligibility screening: DSM-IV diagnosis of bipolar I disorder, manic or mixed episode, confirmed by K-SADS-PL and clinical history; symptom severity, assessed by the YMRS; physical and neurological examination, including the Mini-Mental State Examination (21) ; laboratory evaluations; and an ECG. Current medications and use of alcohol and/or illicit drugs were also recorded. Patients who met all eligibility criteria were randomly assigned to receive either oxcarbazepine or placebo. During the 2-week titration period, the oxcarbazepine dose was titrated upward by 300 mg every 2 days to a maximum dose level of 900–2400 mg/day based on body weight or to the maximum dose tolerated. At the investigator’s discretion, the dose could be tapered downward by 300 mg/day if the patient experienced intolerable adverse effects. The patient could be maintained at that dose level for the remainder of the titration phase or could have the dose titrated up later in the titration period to reach a maximum tolerated dose. No upward dose adjustments were permitted after the titration period.

Outcome Measures

A clinician such as a psychiatrist, clinical psychologist, or psychometrician with at least 2 years’ experience in treating pediatric patients conducted all efficacy assessments. For consistency, each patient was assessed by the same clinician throughout the study where possible. A prestudy investigators’ meeting was held to review the study protocol, the case report form, and all aspects of how the study would be conducted. Training in YMRS rating was provided at the prestudy meeting. All raters who conducted interviews using the YMRS were required to pass a certification test. K-SADS-PL training was also provided at the prestudy meeting, although staff at the study sites were familiar with the use of the instrument. Any raters who joined the study after the prestudy meeting received the same rater training individually.

Efficacy Assessments

Efficacy assessments were conducted at the end of each of the first 6 weeks or on early discontinuation. The primary efficacy measure was the change from baseline in the YMRS total score at the end of the study, using the last-observation-carried-forward method. Secondary efficacy measures (also based on last observation carried forward) included the percentage of patients who demonstrated a reduction ≥50% in the YMRS score relative to baseline; the mean change from baseline to end of study in the Children’s Depression Rating Scale (22) ; the mean change from baseline to end of study in the Clinical Global Impression scale modified for bipolar disorder (CGI) (23) ; and the mean change from baseline to end of study in quality of life as measured by the Child Health Questionnaire (24) domain scores.

Safety Assessments

Safety was assessed by monitoring adverse events, vital signs such as pulse and blood pressure, laboratory test results, and findings on ECG and physical and neurological examinations. Assessments were conducted at each study visit and at the end of the down-titration period. Clinical laboratory tests, which included hematology, serum chemistry, dipstick urinalysis, and serum pregnancy test for females of childbearing potential, were performed at screening, at weeks 2 and 6, and at the end of the down-titration period. Physical and neurological examinations and ECGs were performed at screening and at week 6. In addition, a urine pregnancy test was performed at week 4 and a urine drug screen at weeks 2, 4, and 6.

Data Analysis

It was estimated that 55 patients per treatment group would be sufficient to detect a mean difference of eight between oxcarbazepine and placebo in the change from baseline to end of study in the YMRS total score, based on a standard deviation of 13 (24) . This mean difference is detectable with a power of 90%, given a significance level of 5% using a two-sided t test.

A computer-generated randomization list, stratified by age subgroup (children 7–12 years old and adolescents 13–18 years old) and comorbid ADHD diagnosis, was used to assign patients to each treatment group. A 1:1 randomization to oxcarbazepine or placebo was used.

The safety population consisted of all patients who underwent random assignment into the treatment phase and received at least one dose of study drug. All patients who entered the treatment phase, received at least one dose of study drug, and had at least one efficacy assessment after baseline were included in the intent-to-treat population.

Statistical analyses of the efficacy of oxcarbazepine were conducted with the data set from visit 8 (day 42, final assessment before the down-titration period) or from the last-observation-carried-forward data set, based on the intent-to-treat population. All hypothesis tests were two-sided and assessed at the 5% significance level.

For continuous efficacy variables, an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) model was used, with corresponding baseline measurement, age group (7–12 years versus 13–18 years), and ADHD diagnosis as covariates and treatment group and study center as factors. Confidence intervals and point estimates for treatment differences in changes from baseline and within-group changes from baseline were provided. If the parametric assumptions were not met, Wilcoxon rank sum tests were used to analyze the primary efficacy variable.

The YMRS 50% response rate at each visit and at end of study was compared for the two treatment groups using the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test with study center as a blocking factor. This procedure tests for the association between treatment groups and the number of responders, adjusting for study center. For the remaining secondary categorical efficacy variables, between-treatment comparisons were made using a modified ridit transformation with the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel procedure, adjusting for age group and ADHD diagnosis. This is a distribution-free nonparametric test used to compare the changes in scores on the 7-point modified CGI scale between treatment groups. In addition, post hoc analyses evaluated differences between the two age groups.

RESULTS

Of 190 patients screened, 116 patients were randomly assigned to double-blind treatment with either oxcarbazepine (N=59) or placebo (N=57) ( Figure 1 ). The number of patients randomly assigned per site ranged from 1 to 25, with a mean of 5.8 patients. All patients in the oxcarbazepine group and all but one in the placebo group received at least one dose of study drug and were included in the safety analysis. One patient in the placebo group who did not receive placebo was excluded from the intent-to-treat population. Four patients in the oxcarbazepine group and one in the placebo group were excluded from the intent-to-treat population because they withdrew from the study before any postrandomization data were collected. Thus, the efficacy analysis included 55 patients in the oxcarbazepine group and 55 in the placebo group. Twenty patients (34%) in the oxcarbazepine group and 24 (42%) in the placebo group withdrew from the study before it was completed. For the oxcarbazepine group, reasons for withdrawal included adverse events (N=11, 19%), unsatisfactory therapeutic effect (N=6, 10%), withdrawal of consent (N=2, 3%), and unknown (N=1, 2%). For the placebo group, reasons for withdrawal included adverse events (N=2, 4%), unsatisfactory therapeutic effect (N=14, 25%), withdrawal of consent (N=6, 11%), and administrative problems (N=2, 4%).

a Another subject withdrew because of adverse events during the down-titration period, after completing the final assessment of the maintenance period.

b In each treatment group, 55 subjects completed the primary outcome measure (the Young Mania Rating Scale) at least once after assignment to a treatment group.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics for the two groups are summarized in Table 1 . No statistically significant differences were observed between the two groups on any of the characteristics. The mean age at onset of bipolar illness was approximately 10 years for both treatment groups, and the mean number of manic or hypomanic episodes within the past year was similar for the two groups. Mean baseline scores on the YMRS, the Children’s Depression Rating Scale, and the modified CGI were also similar. Approximately the same percentage of patients in each group had a concomitant diagnosis of ADHD, and the mean age at ADHD diagnosis was similar in the two groups.

The mean dose of oxcarbazepine given to patients who completed the study was 1515 mg/day, and the median exposure to the drug was 48 days. The mean dose was lower for patients 7–12 years old than for those 13–18 years old (1200 mg/day and 2040 mg/day, respectively). The median exposure to oxcarbazepine was similar for the two age groups (47 days and 49 days, respectively).

Fourteen patients in the oxcarbazepine group and 16 in the placebo group received concomitant treatment with diphenhydramine. Eighteen patients in each group continued the use of stimulant medications during the study.

Efficacy

As shown in Figure 2 and Table 2 , mean YMRS scores decreased among patients in both the oxcarbazepine and placebo groups from baseline for the intent-to-treat population, using the last-observation-carried-forward method. The difference between groups was not statistically significant at any time point. At endpoint, the adjusted mean change from baseline in YMRS scores was –10.90 for the oxcarbazepine group and –9.79 for the placebo group. Age group was not a significant covariate in the model. Decreases from baseline to endpoint were also noted for both the oxcarbazepine and placebo groups in mean total scores on the Children’s Depression Rating Scale and the modified CGI, and global health and global behavior scores on the Child Health Questionnaire ( Table 2 ); again, the differences between groups were not statistically significant.

a The efficacy analysis used the last-observation-carried-forward method.

There were no statistically significant differences between the oxcarbazepine and placebo groups in study completion, age at diagnosis, duration of illness, and treatment response. No statistically significant differences were observed between treatment groups, for either age group, in total Children’s Depression Rating Scale scores or global behavior scores on the Child Health Questionnaire.

For the total population at the study endpoint, using the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test between treatment groups, 42% of the oxcarbazepine group and 26% of the placebo group achieved at least a 50% reduction in YMRS scores relative to baseline, although the difference between groups was not statistically significant. Results on this measure for the two age groups were also compared. Forty-one percent of the children in the oxcarbazepine group and 17% of those in the placebo group achieved at least a 50% reduction in YMRS scores. Among adolescents, the results on this measure were similar for oxcarbazepine and placebo (43% and 40%, respectively). The response rates were similar for children and adolescents treated with oxcarbazepine.

Safety

Overall, 84% of the patients experienced one or more adverse events; the incidence of adverse events was higher in the oxcarbazepine group (90%) than in the placebo group (79%). For the total sample, six adverse events met the criteria of occurring in at least 5% of the oxcarbazepine group with an incidence of at least twice that in the placebo group: dizziness, nausea, somnolence, diplopia, fatigue, and rash ( Table 3 ). For the 7–12-year-old subgroup, in addition to these adverse events, blurred vision, increased appetite, toothache, and insect bite also met the criteria, whereas for the 13–18-year-old subgroup, vomiting and exacerbation of bipolar disorder additionally met the criteria, although fatigue did not.

The majority of adverse events were mild to moderate in severity and were transient, occurring early in the study. For the oxcarbazepine group, the incidences of diplopia, dizziness, and nausea were highest during the 2-week titration phase and decreased through the end of the study: on day 7, diplopia was reported in 6% of the subjects, dizziness in 22%, and nausea in 20%; on day 14, diplopia was reported in 17%, dizziness in 28%, and nausea in 21%; on day 21, diplopia was reported in 9%, dizziness in 28%, and nausea in 16%; on day 28, diplopia was reported in 10%, dizziness in 20%, and nausea in 10%; on day 35, diplopia was reported in 8%, dizziness in 18%, and nausea in 5%; and at endpoint, diplopia was reported in 2%, dizziness in 10%, and nausea in 7%). More discontinuations due to adverse events occurred in the oxcarbazepine group (N=11, 19%) than in the placebo group (N=2, 4%, including one patient who discontinued during the down-titration period). The mean duration of treatment before discontinuation was similar for the oxcarbazepine and placebo groups (21 days and 23 days, respectively).

The incidence of psychiatric adverse events was similar between treatment groups: 12 (20%) in the oxcarbazepine group and 10 (18%) in the placebo group. Six patients in the oxcarbazepine group and none in the placebo group experienced adverse events that met criteria for serious adverse events, and all required hospitalization. The serious adverse events were exacerbation of bipolar disorder (N=3), aggressive outburst (N=1), suicide attempt (N=1), and inappropriate sexual behavior (N=1). The investigators at the sites where these adverse events occurred used their clinical judgment to determine whether the event was related to the study medication. Three of the serious adverse events were suspected to be related to the oxcarbazepine (one instance each of exacerbation of bipolar disorder, aggressive behavior, and suicide attempt), and three were judged to be unrelated to the oxcarbazepine (two instances of exacerbation of bipolar disorder and one instance of inappropriate sexual behavior). Two of these six patients completed the study. The other four patients discontinued the study within 6 days of their first dose of oxcarbazepine, and no postrandomization YMRS scores were obtained for them.

No clinically significant differences were noted between treatment groups in vital signs, laboratory tests, or findings on physical examination or ECG. None of the patients developed hyponatremia. The mean change in body weight from baseline to end of study was 0.83 kg for the oxcarbazepine group and –0.13 kg for placebo group (F=5.18, df=1, p=0.025).

DISCUSSION

Oxcarbazepine was not significantly superior to placebo on the primary efficacy measure, which was change in mean YMRS score from baseline to endpoint. Scores decreased for both treatment groups, but not to a degree that would be considered clinically significant. Similarly, there were no significant differences between groups on the secondary efficacy measures of change from baseline to endpoint in Children’s Depression Rating Scale scores, modified CGI scores, and global health and behavior scores on the Child Health Questionnaire as well as on treatment response rates.

The response rate (defined as a reduction of ≥50% in YMRS scores from baseline to endpoint) of 42% in this study was similar to response rates obtained in an open trial of divalproex, lithium, and carbamazepine for the treatment of bipolar disorder in children and adolescents (25) .

Overall, the incidence of adverse events was higher in the oxcarbazepine group than in the placebo group, and the majority of the adverse events were mild to moderate in severity and occurred during the titration period. Rates of diplopia, dizziness, and nausea were the highest during this early period, particularly in the younger age group. The dosing strategy used in this study may have contributed to the emergence of these adverse events early in the study. The titration of oxcarbazepine was rapid, with a 300 mg increment every 2 days to a maximum of 900–2400 mg per day within 2 weeks, based on body weight. A lower starting dose (150 mg/day) and slower titration might improve tolerability. Withdrawal due to adverse events was higher in the oxcarbazepine group (19%) than in the placebo group (4%), and six patients in the oxcarbazepine group and none in the placebo group experienced serious adverse events. There were no clinically significant changes in vital signs, laboratory values, or ECG findings between the treatment groups. The mean weight body weight change was higher among patients in the oxcarbazepine group than among those in the placebo group, but it was a modest mean weight increase of less than 1 kg.

In diagnostic characteristics, age at onset of illness, and rates of ADHD, the study sample was similar to a well-characterized sample of youths with bipolar disorder (1) . In our sample, the onset of ADHD preceded that of bipolar disorder (as measured by mean age at onset), as has been reported for other samples of youths with bipolar disorder (26) .

Recently, Emslie et al. (27) reviewed methodological issues in pediatric trials of antidepressants that may account for the failure to demonstrate the superiority of some antidepressants to placebo, and many of these issues are germane to our study. The number of sites in a study and the number of patients per site can affect medication and placebo response rates; fewer sites and more patients per site may result in a greater separation in response rates. Our study used a large number of sites and as few as one patient per site. Inclusion or exclusion of certain comorbid disorders also may affect outcome. For example, in our study, aside from stimulants for the treatment of ADHD, psychotropic medications for the treatment of comorbid disorders were not allowed, consequently limiting the inclusion of patients with comorbid disorders. Treatment duration may affect study outcome, particularly if the trial is not long enough to allow a full treatment response. This study consisted of a 2-week titration period followed by a 4-week maintenance period. It is possible that 4 weeks of maintenance treatment was too brief for an optimal treatment response. Finally, outcome measures can influence treatment response results. Ideally, outcome measures in child studies should be child based. However, the current standard for assessing treatment response in pediatric patients with bipolar disorder is the YMRS, which is an adult-derived instrument. It is conceivable that the use of a child-based instrument to assess pediatric mania might have altered the outcome of this study.

The findings of this study must be interpreted in light of several limitations, including the minimal ethnic diversity of the study sample, the exclusion of concomitant psychotropic medications, the restriction of comorbid diagnoses, and the exclusion of psychotic patients, inpatients, and patients at high risk of suicidality.

CONCLUSION

This is the first report of a multicenter, placebo-controlled trial to evaluate the efficacy of oxcarbazepine in the treatment of bipolar I disorder, manic or mixed, in children and adolescents. There was no statistically significant difference between the oxcarbazepine-treated patients and those who received placebo on the primary efficacy measure for the total sample. While the overall adverse event profile was similar to that reported for patients with epilepsy, the incidence of psychiatric adverse events for both the oxcarbazepine and placebo groups was higher than that reported for the epilepsy population.

1. Geller B, Zimmerman B, Williams M, Bolhofner K, Craney JL, DelBello MP, Soutullo CA: Diagnostic characteristics of 93 cases of prepubertal and early adolescent bipolar disorder phenotype by gender, puberty, and comorbid attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2000; 10:157–164Google Scholar

2. Geller B, Tillman R, Craney JL, Bolhofner K: Four-year prospective outcome and natural history of mania in children with a prepubertal and early adolescent bipolar disorder phenotype. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2004; 61:459–467Google Scholar

3. Perlis RH, Miyahara S, Marangell LB, Wisniewski SR, Ostacher M, DelBello MP, Bowden CL, Sachs GS, Nierenberg AA: Long-term implications of early onset in bipolar disorder: data from the first 1,000 participants in the systematic treatment enhancement program for bipolar disorder (STEP-BD). Biol Psychiatry 2004; 55:875–881Google Scholar

4. Wilens T, Biederman J, Dwon A, Ditterline J, Forkner P, Moore H, Swezey A, Snyder L, Henin A, Wozniak J, Faraone S: Risk of substance use disorders in adolescents with bipolar disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2004; 43:1380–1386Google Scholar

5. Kowatch RA, Fristad M, Birmaher B, Wagner KD, Findling RL, Hellander M; Child Psychiatric Workgroup on Bipolar Disorder: Treatment guidelines for children and adolescents with bipolar disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2005; 44:213–235Google Scholar

6. Wagner KD: Management of bipolar disorder in children and adolescents. Psychopharmacol Bull 2002; 36:151–159Google Scholar

7. DelBello MP, Findling RL, Kushner S, Wang D, Olson WH, Capece JA, Fazzio L, Rosenthal NR: A pilot controlled trial of topiramate for mania in children and adolescents with bipolar disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2005; 44:539–547Google Scholar

8. Tohen M, Kryzhanovskaua L, Carlson G, DelBello M, Wozniak J, Kowatch R, Wagner KD, Findling R, Lin D, Robertson-Plouch C, Xu W, Huang X, Dittman R, Biederman J: Olanzapine in the treatment of acute manic or mixed episodes in adolescents: a 3-week randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study. Poster presented at the 44th annual meeting of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology, Dec 11–15, 2005, Waikoloa, HawaiiGoogle Scholar

9. Oxcarbazepine prescribing information, Novartis Pharmaceuticals, in Physicians Desk Reference, Thompson Healthcare, Montvale, NJ, 2005Google Scholar

10. Hellewell J: Oxcarbazepine (Trileptal) in the treatment of bipolar disorders: a review of efficacy and tolerability. J Affect Disord 2002; 72:S23–S34Google Scholar

11. Hirschfeld R, Kasper S: A review of the evidence for carbamazepine and oxcarbazepine in the treatment of bipolar disorder. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2004; 7:507–522Google Scholar

12. Emrich HM, Altmann H, Dose M, von Zerssen D: Therapeutic effects of GABA-ergic drugs in affective disorders: a preliminary report. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 1983; 19:369–372Google Scholar

13. Emrich KM, Dose M, von Zerssen D: Action of sodium valproate and of oxcarbazepine in patients with affective disorders, in Anticonvulsants in Affective Disorders. Edited by Emrich HM, Okuma T, Muller AA. Amsterdam, Excerpta Medica, 1984, pp 45–55Google Scholar

14. Emrich HM, Dose M, von Zerssen D: The use of sodium valproate, carbamazepine, and oxcarbazepine in patients with affective disorders. J Affect Disord 1985; 8:243–250Google Scholar

15. Emrich HM: Studies with oxcarbazepine (Trileptal) in acute mania. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1990; 5:83–88Google Scholar

16. Müller AA, Stoll KD: Carbamazepine and oxcarbazepine in the treatment of manic syndromes: studies in Germany, in Anticonvulsants in Affective Disorders. Edited by Emrich HM, Okuma T, Müller AA. Amsterdam, Excerpta Medica, 1984, pp 139–147Google Scholar

17. Davanzo P, Nikore V, Yehya N, Stevenson L: Oxcarbazepine treatment of juvenile-onset bipolar disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2004; 14:344–345Google Scholar

18. Teitelbaum M: Oxcarbazepine in bipolar disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2001; 40:993–994Google Scholar

19. Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U, Flynn C, Moreci P, Williamson D, Ryan N: Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children–Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997; 36:980–988Google Scholar

20. Young RC, Biggs JT, Ziegler VE, Meyer DA: A rating scale for mania: reliability, validity, and sensitivity. Br J Psychiatry 1978; 133:429–435Google Scholar

21. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR: “Mini-Mental State”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975; 12:189–198Google Scholar

22. Poznanski EO, Miller E, Salguero C, Kelsh RC: Preliminary studies of the reliability and validity of the children’s depression rating scale. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry 1984; 23:191–197Google Scholar

23. Spearing MK, Post RM, Leverich GS, Brandt D, Nolen W: Modification of the Clinical Global Impressions (CGI) scale for use in bipolar illness (BP): the CGI-BP. Psychiatry Res 1997; 73:159–171Google Scholar

24. Landgraf JM, Abetz L, Ware JE: The Child Health Questionnaire (CHQ): A User’s Manual, Second Printing. Boston, HealthAct 1999Google Scholar

25. Kowatch RA, Suppes T, Carmody TJ, Bucci JP, Hume JH, Kromelis M, Emslie GJ, Weinberg WA, Rush J: Effect size of lithium, divalproex sodium, and carbamazepine in children and adolescents with bipolar disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2000; 39:713–720Google Scholar

26. Tillman R, Geller B, Bolhofner K, Craney JL, Williams M, Zimerman B: Ages of onset and rates of syndromal and subsyndromal comorbid DSM-IV diagnoses in a prepubertal and early adolescent bipolar disorder phenotype. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2003; 42:1486–1493Google Scholar

27. Emslie GJ, Ryan ND, Wagner KD: Major depressive disorder in children and adolescents: clinical trial design and antidepressant efficacy. J Clin Psychiatry 66(suppl 7):14–20, 2005Google Scholar