Ten-Year Stability of Depressive Personality Disorder in Depressed Outpatients

Abstract

Objective: The purpose of this study was to examine the long-term stability of depressive personality disorder. Method: The subjects included 142 outpatients with axis I depressive disorders at study entry; 73 had depressive personality disorder. The patients were assessed by using semistructured diagnostic interviews at baseline and in four follow-up evaluations at 2.5-year intervals over 10.0 years. Follow-up data were available for 127 (89.4%) of the patients. Results: The 10.0-year stability of the diagnoses of depressive personality disorder was fair, and the rate of depressive personality disorder declined over time. The dimensional score was moderately stable over 10.0 years. Growth curve analyses revealed a sharp decline in the level of depressive personality disorder traits between the baseline and 2.5-year assessments, followed by a gradual linear decrease. Reductions in depressive personality disorder traits were associated with remission of the axis I depressive disorders. Finally, depressive personality disorder at baseline predicted the trajectory of depressive symptoms over time in patients with dysthymic disorder. Conclusions: Depressive personality disorder is moderately stable, particularly when assessed with a dimensional approach. However, the diagnosis rate and traits of depressive personality disorder tend to decline over time. The degree of stability for depressive personality disorder is comparable to that for the axis II disorders in the main text of DSM-IV. Finally, depressive personality disorder has prognostic implications for the course of axis I mood disorders, such as dysthymic disorder.

Although the concept of depressive personality disorder has a long history (1 – 4) , interest in this construct has increased since 1990 (5 – 13) . To recognize this growing body of research and encourage further work in this area, DSM-IV included depressive personality disorder in the appendix as a category requiring further study.

Recent studies have demonstrated that although depressive personality disorder overlaps with axis I mood disorders, especially dysthymic disorder, it is both conceptually and empirically distinct. The DSM-IV criteria for dysthymic disorder require persistent depressed mood and include several vegetative symptoms in the list of associated symptoms. In contrast, depressive personality disorder is defined in terms of personality traits or dispositions, often of a cognitive nature. A number of studies using a variety of study groups have demonstrated that the association between diagnoses of depressive personality disorder and dysthymic disorder is modest, with fewer than one-half of the individuals with depressive personality disorder meeting the criteria for dysthymia and fewer than one-half of the individuals with dysthymia meeting the criteria for depressive personality disorder (5 , 7–12) . Depressive personality disorder is also fairly distinct from the axis II disorders in the main text of DSM-IV. Although there is substantial comorbidity between depressive personality disorder and the main-text personality disorders, the magnitude of these associations is modest and no greater than that among the main-text axis II conditions (9 – 12) .

According to DSM-IV, personality disorders are characterized by a persistent pattern of maladaptive traits that persist throughout the life course. However, research on the stability of personality disorders suggests that they tend to wax and wane and may not have greater stability than many axis I disorders (14) . For example, in the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study, which focuses on schizotypal, borderline, avoidant, and obsessive-compulsive personality disorders, the mean diagnostic stability over 1 year was 41% and the mean number of criteria met decreased significantly for each disorder (14) .

Only limited data are available on the long-term stability of depressive personality disorder. In a 1-year follow-up of subjects with long-standing mild depressive features, Phillips and colleagues (12) found moderate stability for both the diagnosis of depressive personality disorder, with a kappa of 0.55, and depressive personality disorder dimensional scores, with an intraclass correlation (ICC) of 0.62. In a 2.5-year follow-up of outpatients with axis I depressive disorders, we found fair stability for the diagnosis of depressive personality disorder (kappa=0.37) and moderate stability for dimensional scores (ICC=0.51) (9) . Finally, in a 2-year follow-up of the subjects in the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study, Markowitz et al. (10) found poor to fair stability for the diagnosis of depressive personality disorder (kappa=0.29) and moderate stability for dimensional scores (ICC=0.41).

Axis II disorders tend to adversely influence the treatment response and course of axis I disorders (15) . There are limited data suggesting that depressive personality disorder may also have negative prognostic implications for axis I depressive disorders. In a 15-week clinical trial of treatments for major depressive disorder, Shahar and colleagues (16) found that after control for other axis II traits, depressive personality disorder traits predicted significantly less improvement in depressive symptoms. In a 2-year naturalistic follow-up of subjects with major depressive disorder from the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study, Markowitz et al. (10) found that a baseline diagnosis of depressive personality disorder predicted a significantly lower likelihood of remission from major depression. Finally, in a 2.5-year naturalistic follow-up, we found that among outpatients with dysthymic disorder, depressive personality disorder predicted significantly less change in depressive symptoms (9) . This latter study is important in that it indicates that depressive personality disorder contributes unique prognostic information over and above the near-neighbor diagnosis of dysthymia.

In the present study we report the long-term (10.0-year) stability of depressive personality disorder in a group of 127 outpatients with axis I depressive disorders. It extends our earlier report (9) on the 2.5-year stability of depressive personality disorder in the same subjects by presenting the results of the 2.5-, 5.0-, 7.5-, and 10.0-year follow-up evaluations. We address four questions: 1) What is the 10.0-year stability of the depressive personality disorder diagnosis and the dimensional score? 2) Do the rate of depressive personality disorder diagnosis and the dimensional score change over time? 3) Is remission from axis I depressive disorders associated with a decrease in the level of depressive personality disorder traits? and 4) Does depressive personality disorder predict the 10.0-year trajectory of dysthymic disorder?

Method

Subjects

The method is described in previous publications (17 , 18) and is only briefly summarized here. At baseline, the study group included 142 outpatients with DSM-III-R major depression and/or dysthymia. The patients were 18–60 years old and spoke English. In addition, as this was part of a larger family study (18) , patients were required to have knowledge of at least one first-degree relative. The patients were recruited between 1988 and 1993 from consecutive admissions to Stony Brook University’s Outpatient Psychiatry Department (50.0%) and the Psychological Center (40.8%). In addition, a few patients were referred from the Counseling Center (7.0%) and a community mental health center (2.1%). The participants were given a complete description of the study, after which written informed consent was obtained.

We conducted follow-up assessments at 2.5-year intervals over 10.0 years. Follow-up evaluations were available for 108 patients (76.1%) at the 2.5-year follow-up, 111 (78.2%) at the 5.0-year follow-up, 109 (76.8%) at the 7.5-year follow-up, and 102 (71.8%) at the 10.0-year follow-up. Of the original participants, 127 patients (89.4%) had at least one follow-up assessment and thus contributed to the analyses described in this study. These patients did not significantly differ from those who did not complete any of the follow-ups (N=15) on demographic characteristics or baseline traits of depressive personality disorder.

Most of the patients were female (70.9%) and Caucasian (89.8%). The patients had a mean age of 31.4 years (SD=9.1) and 13.6 (SD=2.3) years of formal education. At entry into the study, 29.9% were married, 21.3% were divorced or separated, 1.6% were widowed, and 47.2% had never married. Socioeconomic status based on the Hollingshead’s four-factor index of social position (19) was known for 114 of the patients: 12.3% of the subjects were in social class I, 28.1% were in class II, 24.6% were in class III, 20.2% were in class IV, and 14.9% were in class V. At the baseline evaluation, 31.5% of the patients had a current diagnosis of major depression, 28.3% had a current diagnosis of dysthymia, and 40.2% had current diagnoses of both dysthymia and major depression. At entry into the study, 57.5% of the patients met Akiskal’s criteria for depressive personality disorder (1) . In addition, 31.5% had a current anxiety disorder, 8.7% had a current substance use disorder, and 45.7% had a personality disorder other than depressive personality disorder.

The study was naturalistic; hence there was no attempt to control treatment. The participants (N=127) received one or more antidepressant medications for a mean of 28.3% of the follow-up period (SD=31.2%) and some form of psychotherapy or counseling with a mental health professional for 28.7% (SD=27.7%) of the follow-up period.

Measures

The baseline assessment included the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID) (20) , the 24-item Modified Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) (21) , and the Personality Disorder Examination (22) , a semistructured interview assessing axis II personality disorders. The study was initiated before the publication of DSM-IV, and so we could not assess the DSM-IV criteria for depressive personality disorder in the baseline evaluation. Instead, a semistructured interview assessing Akiskal’s criteria for depressive personality disorder (1) , derived from the work of Schneider (4) , was appended to the Personality Disorder Examination. We used this interview in several previous studies and documented good interrater reliability for depressive personality disorder (7 , 8) .

A participant was diagnosed with depressive personality disorder if five or more of the following characteristics were present: 1) quiet, passive, and nonassertive; 2) gloomy, pessimistic, and incapable of fun; 3) self-critical, self-reproaching, and self-derogatory; 4) skeptical, hypercritical, and complaining; 5) conscientious and self-disciplining; 6) brooding and given to worry; and 7) preoccupied with inadequacy, failure, and negative events. A dimensional score of 0–7 was derived by counting the number of criteria that were present. In keeping with the conventions of the Personality Disorder Examination, at least one criterion had to be present before age 25. For a criterion to be scored as present, it had to be evident the majority of time for at least the past 5 years, as well as throughout the past year. In addition, the criterion could not have occurred exclusively during a major depressive episode. The DSM-IV exclusion of depressive personality disorder that is “better accounted for” by dysthymic disorder was not employed, as it is unclear how this can be determined.

The follow-up evaluations included the 24-item HAM-D, the Personality Disorder Examination, and the interview for Akiskal’s depressive personality disorder criteria. At the 7.5- and 10.0-year evaluations, DSM-IV depressive personality disorder was also assessed by using the depressive personality disorder section from the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personality Disorders (SCID-II) (23) . In the follow-up interviews, the Akiskal criteria and DSM-IV depressive personality disorder traits were scored as present only if they were evident for the majority of the time during the previous 2.5 years and throughout the previous year.

All assessments were conducted by master’s- and doctoral-level clinicians (including D.N.K.) and advanced graduate students in clinical psychology. Generally, the raters interviewing each patient differed among the follow-up evaluations. All follow-up interviewers were blind to the results of the baseline assessment.

Interrater reliability for the baseline evaluations with the SCID, HAM-D, and Personality Disorder Examination and the follow-up evaluations with the HAM-D was generally good, as documented elsewhere (17 , 24) . Interrater reliability of Akiskal’s criteria at baseline was assessed through independent evaluations of 15 videotaped interviews. The kappa for the diagnostic concordance of depressive personality disorder was 0.70; the ICC for the number of depressive personality disorder traits was 0.81. Interrater reliability of follow-up evaluations of Akiskal’s criteria was assessed by having a second diagnostician independently reevaluate 33 randomly selected patients within 3 months of their 7.5- or 10.0-year follow-up. The kappa for the diagnostic concordance of depressive personality disorder was 0.72; the ICC for the dimensional score was 0.67.

Data Analysis

Kappa was used to assess the stability of the depressive personality disorder diagnosis, and McNemar’s test was used to examine change in diagnosis. ICCs were used to assess the stability of the dimensional score. Pearson correlations were used to examine the association between dimensional scores assessed with Akiskal’s criteria (1) and with DSM-IV. We employed growth curve modeling to examine the stability and change of the depressive personality disorder dimensional score, using the Hierarchical Linear Modeling program (25) . Repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to explore whether remission of axis I depressive disorders was associated with change in depressive personality disorder traits. Finally, growth curve modeling was used to determine whether depressive personality disorder predicted the course of depressive symptoms in patients with a baseline diagnosis of dysthymia. For all statistical tests, alpha was set at p<0.05.

Results

Stability and Change in Diagnosis

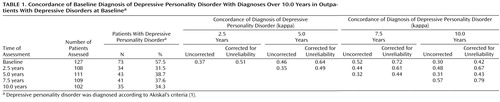

The data on the 2.5-year diagnostic stability of depressive personality disorder were previously published (9) . Data on the 10.0-year stability of diagnoses based on Akiskal’s criteria are presented in Table 1 . The kappas for the concordance between the initial and follow-up assessments ranged from 0.30 to 0.52, with a median of 0.42. The concordance between the baseline and 10.0-year assessments was fair. Stability estimates are attenuated by imperfect interrater reliability; hence the stability coefficients were corrected for attenuation by using the short-term test-retest interrater reliability coefficient (kappa=0.72) from our reliability study. Corrected for unreliability, the kappas ranged from 0.42 to 0.72, with a median of 0.58. Corrected for attenuation, the 10.0-year stability of depressive personality disorder was moderate.

Stability coefficients were also calculated for each pair of follow-up visits. The diagnostic concordance between different pairs of follow-up assessments ranged from 0.31 to 0.57, with a median of 0.44. Corrected for attenuation, the kappas ranged from 0.43 to 0.79, with a median of 0.55. It is interesting that there did not appear to be systematic differences in concordance as a function of the length of the interval between assessments.

Next we looked at changes in the rates of depressive personality disorder diagnosis between the baseline and follow-up assessments ( Table 1 ). McNemar’s test for differences between correlated proportions indicated that the proportion of patients with a diagnosis of depressive personality disorder at baseline was significantly higher than the proportion at each of the follow-ups (p<0.001 for all). However, the proportion did not differ significantly between any of the pairs of follow-ups.

Stability and Change in Dimensional Score

We used growth curve modeling to examine the stability of the number of criteria for depressive personality disorder across the five assessments. To derive an ICC for stability across all five assessments, we estimated an unconditional means model (i.e., the model included a term for the intercept but not the slope). This yielded an ICC of 0.57.

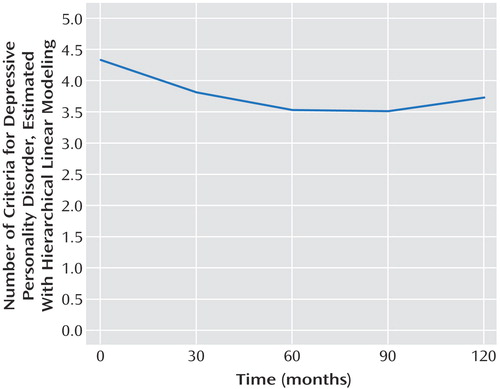

Next, we used growth curve modeling to explore linear and nonlinear changes in the trajectory of the dimensional score over time. The mean dimensional scores were 4.39 (SD=1.90) at baseline, 3.51 (SD=2.03) at 2.5 years, 3.52 (SD=2.12) at 5.0 years, 3.75 (SD=2.03) at 7.5 years, and 3.66 (SD=2.02) at 10 years. We computed an unconditional growth model, which includes parameters for both the intercept (estimated score at baseline) and slope (rate of change over time). The unconditional growth model exhibited a significant improvement in fit over the unconditional means model (χ 2 =20.84, df=1, p<0.001), indicating that there was a linear trend in the trajectory of the dimensional score over time. We then examined nonlinear trajectories by determining whether the addition of a quadratic or cubic term for time significantly improved model fit. When a quadratic term for time was added to the model, there was a significant improvement in fit compared to the unconditional growth model (χ 2 =21.22, df=4, p<0.001). However, adding a cubic term did not further improve model fit ((χ 2 =10.55, df=5, p>0.05). Figure 1 shows a plot of the growth curve estimated with hierarchical linear modeling and indicates that the dimensional score for depressive personality disorder declined sharply from the baseline assessment to the 2.5-year follow-up and then continued to decrease more gradually in subsequent assessments. Although there appears to be a slight increase in depressive personality disorder traits at the 10.0-year follow-up, this was not statistically significant.

a Depressive personality disorder was assessed according to Akiskal’s seven criteria (1).

Stability of DSM-IV Diagnosis

The DSM-IV criteria for depressive personality disorder were assessed at the 7.5- and 10.0-year follow-ups. At 7.5 years, 18.5% of the patients met the DSM-IV criteria, and at 10.0 years 16.0% met the DSM-IV criteria. These rates are lower than the proportions meeting Akiskal’s criteria at the corresponding evaluations ( Table 1 ). Nonetheless, there was a moderate level of concordance between the two criteria sets: the kappas for the associations between the Akiskal and DSM-IV criteria were 0.54 and 0.51 at 7.5 and 10.0 years, respectively. Pearson correlations between the total number of Akiskal and DSM-IV traits of depressive personality disorder at the 7.5- and 10.0-year follow-ups were 0.76 (N=106, p=0.01) and 0.67 (N=100, p=0.01), respectively.

The kappa for the stability of the DSM-IV diagnosis between the 7.5- and 10.0-year follow-ups was 0.57. This was identical to the value for this interval based on Akiskal’s criteria. The ICC representing the stability of the dimensional score between the 7.5- and 10.0-year assessments was 0.71, which was similar to the corresponding value for Akiskal’s criteria (ICC=0.74).

Remission of Axis I Depressive Disorders

Given the significant changes in depressive personality disorder over time, we examined whether change in traits of depressive personality disorder was associated with remission of axis I depressive disorders ( Table 2 ). We used a HAM-D score of less than 8 to indicate remission and a score of 8 or more to indicate nonremission. In order to conserve space, only the data for the 5.0- and 10.0-year follow-ups are presented. Repeated-measures ANOVAs revealed a significant main effect for remission status at both the 5.0-year follow-up (F=24.68, df=1, 108, p<0.001) and the 10.0-year follow-up (F=31.12, df=1, 100, p<0.001). Patients who were symptomatic at follow-up exhibited higher levels of depressive personality disorder traits across both the baseline and follow-up assessments. In addition, there were significant main effects for time at both the 5.0-year assessment (F=28.28, df=1, 108, p<0.001) and 10.0-year assessment (F=15.77, df=1, 100, p<0.001). This reflects the fact that the mean number of traits decreased over time. Finally, the main effects in both analyses were qualified by a significant interaction between remission status and time (baseline to 5.0 years: F=10.40, df=1, 108, p=0.002; baseline to 10.0 years: F=9.57, df=1, 100, p=0.0003). Patients with remitted axis I depressive disorders experienced a greater reduction in the mean number of depressive personality disorder traits at both the 5.0- and 10.0-year follow-ups than patients who continued to exhibit depressive symptoms.

Course of Dysthymia

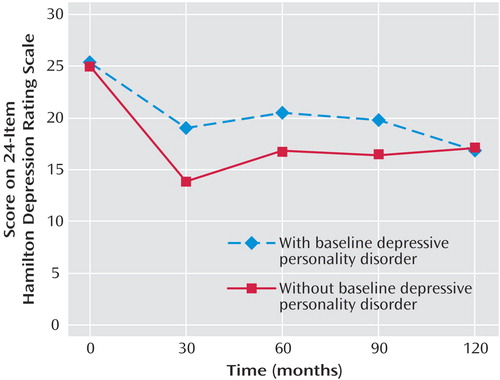

To determine whether a diagnosis of depressive personality disorder conveys prognostic information over and above its near-neighbor category of dysthymic disorder, we examined the effects of baseline depressive personality disorder on the trajectory and outcome of depressive symptoms in the 87 patients who entered the study with dysthymia (with or without a superimposed major depressive episode). This analysis was conducted by using a growth curve model of HAM-D scores at baseline and at 2.5, 5.0, 7.5, and 10.0 years. Time was coded so that the intercepts of the patients’ growth curves reflected their estimated scores at 10.0-year follow-up. As there was a nonlinear effect of time on HAM-D scores, with depression decreasing more rapidly between baseline and 2.5 years than between subsequent assessments, we included a quadratic effect in the model.

A diagnosis of depressive personality disorder at entry into the study significantly predicted the linear trajectory of change in depressive symptoms over time (unstandardized coefficient=0.13, SE=0.06, t=2.26, df=80, p<0.05). Dysthymic patients with depressive personality disorder exhibited a slower rate of improvement in depression over time ( Figure 2 ). In addition, there was a nonsignificant trend for baseline depressive personality disorder to predict the nonlinear component of the slope (unstandardized coefficient=–0.001, SE=0.0006, t=–1.91, df=404, p=0.06). Depressive personality disorder did not predict estimated HAM-D scores at 10.0 years (the intercept) (unstandardized coefficient=0.96, SE=2.24, t=0.43, df=80, p>0.05).

Discussion

Personality disorders are conceptualized as patterns of maladaptive traits that persist over time. However, data on the stability of depressive personality disorder are limited to three studies with durations of 1.0–2.5 years (9 , 10 , 12) . In the present study, we extended our previous 2.5-year study (9) to investigate stability and change in depressive personality disorder over 10.0 years.

The stability of the diagnosis was fair to moderate. The kappas for the concordance between depressive personality disorder at baseline and each follow-up assessment ranged from 0.30 to 0.52. Corrected for attenuation, the kappas ranged from 0.42 to 0.72. These stability estimates are similar to, albeit slightly higher than, the kappa of 0.29 (correction-attenuated kappa=0.47) reported by Markowitz et al. (10) in a 2-year follow-up of depressive personality disorder, and our estimates are generally comparable to the stability of the main-text personality disorders in other studies (26) . In addition, the 10.0-year stability of depressive personality disorder (kappa=0.30) in our study was higher than the 10.0-year stability estimates for most of the main-text personality disorders in the present study group, the kappas for which ranged from –0.03 to 0.33, with a median of 0.09 (unpublished paper by C.E. Durbin and D.N. Klein).

It is interesting that there was no systematic relationship between the magnitude of the stability coefficients and the duration of the follow-up period. Indeed, the association between diagnoses of depressive personality disorder at baseline and follow-up increased slightly with each subsequent assessment before dropping at the last evaluation. Thus, the results do not follow the expected pattern of increasing attenuation over time. This suggests that the lack of stability is more likely to be due to measurement error than to systematic change in depressive personality disorder over time.

We also examined the stability of depressive personality disorder by means of a dimensional approach. Depressive personality disorder traits were moderately stable (ICC=0.57), and somewhat more stable than the diagnosis, over the 10.0-year follow-up period. This is consistent with results in numerous studies demonstrating that dimensional measures of personality disorders have greater stability than categorical diagnoses (27) .

In addition to investigating stability, we examined change in the rates of the diagnosis and in the level of traits over the 10.0-year period. There was a significant reduction in the rate of the diagnosis between the baseline evaluation and each follow-up assessment, but the rate of depressive personality disorder did not vary significantly within the follow-ups. Growth curve analyses revealed a nonlinear decrease in traits of depressive personality disorder, consisting of a sharp decrease between the baseline and 2.5-year assessments and a small decrease in subsequent assessments.

Taken together, these findings suggest that depressive personality disorder may be influenced by clinical state. At baseline, the participants were seeking treatment and exhibited higher levels of depression and impairment than in the follow-up assessments (24) . In contrast, the follow-ups were conducted at times that were independent of the patients’ clinical and treatment status. These results are consistent with results of previous studies indicating a greater reduction in personality disorder traits between the baseline and first follow-up assessment than between subsequent follow-ups (14 , 26) . However, previous studies did not include a sufficient number of assessments to examine nonlinear patterns of change.

This study was initiated before the introduction of DSM-IV; hence most analyses were based on Akiskal’s criteria (1) for depressive personality disorder. However, we also used the DSM-IV criteria in the 7.5- and 10.0-year assessments. Like Hirschfeld and Holzer (5) , we found moderate concordance between the DSM-IV and Akiskal criteria for depressive personality disorder. Moreover, the estimates of the stability of the diagnosis and the dimensional score from 7.5 to 10.0 years were similar with the two sets of criteria.

In light of the indirect evidence suggesting state effects on the assessment of depressive personality disorder, we examined whether changes in the mean number of depressive personality disorder symptoms over time were associated with remission of axis I depressive symptoms. We found that patients who had remissions of depressive symptoms at the 5.0-year and 10.0-year follow-ups showed a significantly greater decrease in depressive personality disorder traits than patients who continued to experience depressive symptoms. This suggests that fluctuations in clinical state may be a source of instability and change in depressive personality disorder. However, these findings should be interpreted cautiously, as they are also consistent with the possibility that stable traits of depressive personality disorder contribute to the persistence of depressive symptoms.

Finally, some investigators have questioned whether a diagnosis of depressive personality disorder provides unique information that goes beyond the diagnosis of dysthymic disorder (see, for example, reference 13). In order to address this issue, we investigated the effect of a baseline diagnosis of depressive personality disorder on the 10.0-year trajectory and outcome of dysthymic disorder. We found that patients with depressive personality disorder exhibited a significantly slower rate of improvement over time. These results support the distinctiveness of the constructs of depressive personality disorder and dysthymic disorder, as the former contributes unique information in predicting the long-term course of the latter. In addition, these data are consistent with findings from previous studies indicating that depressive personality disorder is a negative prognostic indicator for the treatment and course of major depression (10 , 16) .

The present study may be useful in informing the debate over including depressive personality disorder in DSM-V (3 , 6 , 11 , 13) . Our findings indicate that depressive personality disorder has fair to moderate long-term stability that is comparable to or higher than that for the main-text personality disorders (14 , 27) , as well as prognostic utility for the course of dysthymic disorder. Along with previous studies indicating that many patients with depressive personality disorder are not adequately identified by the existing mood and personality disorder categories (5 , 7–12) , these data suggest that adding depressive personality disorder (or revising the existing categories, such as dysthymic disorder, to encompass depressive personality disorder) would enhance the coverage and clinical utility of the classification system. Whether depressive personality disorder, if it is included in DSM-V, should be classified as a mood or personality disorder is controversial. Although the present data are only marginally relevant to this question, studies of the familial aggregation of depressive personality disorder and axis I mood disorders suggest that depressive personality disorder lies on a spectrum of chronic mood disorders (28) .

This study had a number of strengths. We examined stability and change in depressive personality disorder over 10 years by using repeated assessments, semistructured interviews, and raters who were unaware of baseline scores. In addition, our assessments used both categorical and dimensional approaches and, for the last two assessments, used both the Akiskal (1) and DSM-IV criteria for depressive personality disorder. However, the study also had several limitations. First, we used a clinical sample and all patients had axis I mood disorders. Hence, the findings may not generalize to more diagnostically heterogeneous, or community, groups. Second, although our raters were careful in trying to distinguish depressive episodes from depressive personality disorder and to minimize mood-state effects on patients’ reports of depressive personality disorder traits, it is likely that there was some degree of confounding of state and trait. Finally, the patients were asked to report on their behavior over relatively long periods of time (2.5 years), increasing the risk of inaccurate and/or biased recall. Unfortunately, however, long follow-up intervals are necessary in order to attempt to distinguish states from traits.

In conclusion, this study indicates that the stability of the diagnosis of depressive personality disorder over 10 years is fair and that the stability of the dimensional score is moderate. In addition, rates of the diagnosis and levels of traits tend to decline over time. Finally, depressive personality disorder has prognostic implications for the course of axis I mood disorders, such as dysthymic disorder.

1. Akiskal HS: Validating affective personality types, in The Validity of Psychiatric Diagnosis. Edited by Robins L, Barrett J. New York, Raven Press, 1989, pp 217–227Google Scholar

2. Kraepelin E: Manic Depressive Insanity and Paranoia. Edinburgh, E&S Livingston, 1921Google Scholar

3. Phillips KA, Gunderson JG, Hirschfeld RM, Smith LE: A review of the depressive personality. Am J Psychiatry 1990; 147:830–837Google Scholar

4. Schneider K: Psychopathic Personalities. London, Cassell, 1958Google Scholar

5. Hirschfeld RMA, Holzer CE III: Depressive personality disorder: clinical implications. J Clin Psychiatry 1994; 55:10–17Google Scholar

6. Huprich SK: Depressive personality disorder: theoretical issues, clinical findings, and future research directions. Clin Psychol Rev 1998; 118:477–500Google Scholar

7. Klein DN: Depressive personality: reliability, validity, and relation to dysthymia. J Abnorm Psychol 1990; 99:412–421Google Scholar

8. Klein DN, Miller GA: Depressive personality in nonclinical subjects. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:1718–1724Google Scholar

9. Klein DN, Shih JH: Depressive personality: associations with DSM-III-R mood and personality disorders and negative and positive affectivity, 2.5-year stability, and prediction of course of axis I depressive disorders. J Abnorm Psychol 1998; 107:319–327Google Scholar

10. Markowitz JC, Skodol AE, Petkova E, Xie H, Cheng J, Hellerstein DJ, Gunderson JG, Sanislow CA, Grilo CM, McGlashan TH: Longitudinal comparison of depressive personality disorder and dysthymic disorder. Compr Psychiatry 2005; 46:239–245Google Scholar

11. McDermut W, Zimmerman M, Chelminski I: The construct validity of depressive personality disorder. J Abnorm Psychol 2003; 112:49–60Google Scholar

12. Phillips KA, Gunderson JG, Triebwasser J, Kimball CR, Faedda G, Lyoo IK, Renn J: Reliability and validity of depressive personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:1044–1048Google Scholar

13. Ryder AG, Bagby RM, Schuller DR: The overlap of depressive personality disorder and dysthymia: a categorical problem with a dimensional solution. Harv Rev Psychiatry 2002; 10:337–352Google Scholar

14. Shea MT, Stout R, Gunderson J, Morey LC, Grilo CM, McGlashan T, Skodol AE, Dolan-Sewell R, Dyck I, Zanarini MC, Keller MB: Short-term diagnostic stability of schizotypal, borderline, avoidant, and obsessive-compulsive personality disorders. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159:2036–2041Google Scholar

15. Shea MT, Widiger TA, Klein MH: Comorbidity of personality disorders and depression: implications for treatment. J Consult Clin Psychol 1992; 60:857–868Google Scholar

16. Shahar G, Blatt SJ, Zuroff DC, Pilkonis PA: Role of perfectionism and personality disorder features in response to brief treatment for depression. J Consult Clin Psychol 2003; 71:629–633Google Scholar

17. Klein DN, Ouimette PC, Kelly HS, Ferro T, Riso LP: Test-retest reliability of team consensus best-estimate diagnoses of axis I and II disorders in a family study. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:1043–1047Google Scholar

18. Klein DN, Riso LP, Donaldson SK, Schwartz JE, Anderson RL, Ouimette PC, Lizardi H, Aronson TA: Family study of early-onset dysthymia: mood and personality disorders in relatives of outpatients with dysthymia and episodic major depression and normal controls. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995; 52:487–496Google Scholar

19. Hollingshead AB: Four Factor Index of Social Position. New Haven, Conn, Yale University, Department of Sociology, 1975Google Scholar

20. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MB: User’s Guide for the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID). Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1990Google Scholar

21. Miller IW, Bishop S, Norman WH, Maddever H: The Modified Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression: reliability and validity. Psychiatry Res 1985; 14:131–142Google Scholar

22. Loranger AW, Susman VL, Oldham JM, Russakoff M: Personality Disorder Examination (PDE) Manual. Yonkers, NY, DV Communications, 1988Google Scholar

23. First MB, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW: The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personality Disorders (SCID-II). Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1997Google Scholar

24. Klein DN, Schwartz JE, Rose S, Leader JB: Five-year course and outcome of dysthymic disorder: a prospective, naturalistic follow-up study. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:931–939Google Scholar

25. Raudenbush S, Bryk A, Congdon R: HLM 5.05: Hierarchical Linear and Nonlinear Modeling. Lincolnwood, Ill, Scientific Software International, 2001Google Scholar

26. Lenzenweger MF: Stability and change in personality disorder features: the Longitudinal Study of Personality Disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999; 56:1009–1015Google Scholar

27. Grilo CM, McGlashan TH: Stability and course of personality disorders. Curr Opin Psychiatry 1999; 12:157–162Google Scholar

28. Morey LC, Hopwood CJ, Klein DN: Passive-aggressive, depressive, and sadistic personality disorders, in Sage Publications Handbook of Personality Disorders. Edited by O’Donohue WT, Fowler KA, Lilienfeld SO. Thousand Oaks, Calif, Sage Publications (in press)Google Scholar