Smoking Cessation and Schizophrenia

The issue of smoking among those with mental illness is becoming an important one. Smoking rates are declining in the general population (21%), but the prevalence of tobacco use among those with mental illness remains high (50%), particularly among patients with schizophrenia (80%). It has been suggested that for schizophrenia patients, smoking represents a form of self-medication—an attempt to treat underlying biological deficits. Recent evidence suggests that this may indeed be the case. Schizophrenia patients have reduced numbers of nicotinic receptors, the first line of response to nicotine in cigarettes. Smoking normalizes sensory processing deficits in schizophrenia patients and their first-degree relatives. Low expression of the α7 nicotinic receptor has been linked to sensory processing and cognitive deficits in a rodent model of schizophrenia. Nicotinic receptors are pentameric ion channels that flux calcium. They are present both pre- and postsynaptically in brain. Presynaptic activation by nicotine, or the endogenous agonist acetylcholine, results in the release of a large number of different neurotransmitters affecting multiple synapses. It is the neuroadaptation in these transmitter systems that likely results in long-lasting addiction to tobacco. Postsynaptically, the α7 nicotinic receptor lies in or near the NMDA postsynaptic density, where calcium influx leads to changes in gene expression. Indeed, the expression of more than 250 genes has been observed to change in the hippocampus of human smokers. Gene expression was differentially regulated in smoking schizophrenia subjects in specific patterns. Aberrant expression was observed for approximately 70 genes in nonsmoking schizophrenia subjects, and expression was normalized for these genes in smoking schizophrenia subjects, with little change in smoking comparison subjects. These results are consistent with a self-medication hypothesis and also suggest underlying neuropathology in the abnormal response to smoking. A reduced nicotinic receptor level represents one layer of molecular pathology that may be associated with the propensity to smoke in schizophrenia patients. Compensation of this deficit might benefit both drug treatment and smoking cessation in this disorder. A recent phase I trial of DMXB-A, an α7 agonist, resulted in improvements in both sensory deficits and cognition, suggesting that medication targeted to the nicotinic cholinergic system is beneficial for schizophrenic neuropathology. Smoking cessation is also a problem for this patient group. An article by Baker et al. in the current issue reports on a use of nicotine replacement therapy, motivational interviewing, and cognitive behavior therapy for psychotic disorder. The findings indicate that the combination therapy was more effective than nicotine replacement therapy alone. It is possible that DMXB-A, or similar drugs, would provide a better adjuvant treatment for smoking cessation than the nicotine patch.

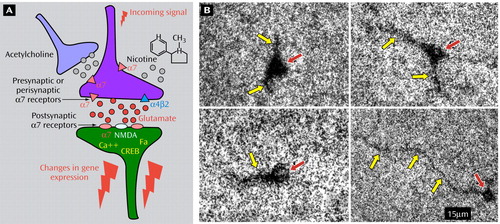

Figure 1. The glutamatergic synapse model on the left shows pre- and postsynaptic α7 nicotinic receptors. The photomicrograph on the right shows presumed interneurons in DBA/2 mouse hippocampus. The interneurons are labeled with [ 125 I]α-bungarotoxin, a selective antagonist at the α7 subtype of nicotinic receptor. Binding is found on both the cell bodies (red arrows) and dendrites (yellow arrows) of the hippocampal cells.