Influence of Comorbid Alcohol and Psychiatric Disorders on Utilization of Mental Health Services in the National Comorbidity Survey

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study sought to determine how comorbidity of psychiatric and substance abuse disorders affects the likelihood of using mental health services. METHOD: The analysis was based on data on adults aged 18–54 years in the National Comorbidity Survey (N=5,393). Users and nonusers of mental health and substance abuse services were compared in terms of their demographic characteristics, recent stressful life events, social support, parental history of psychopathology, self-medication, and symptoms of alcohol abuse/dependence. RESULTS: The prevalence of service utilization varied by diagnostic configurations. Comorbid psychiatric or alcohol disorders were stronger predictors of service utilization than a pure psychiatric or alcohol disorder. Factors predicting utilization of services differed for each disorder. CONCLUSIONS: Since comorbidity increases the use of mental health and substance abuse services, research on the relationship of psychiatric and alcohol-related disorders to service utilization needs to consider the coexistence of mental disorders. Attempts to reduce barriers to help seeking for those in need of treatment should be increased.

Many individuals meet diagnostic criteria for multiple psychiatric disorders (1–6). Of persons ever meeting criteria for a DSM-III-R diagnosis, 56% also met criteria for another disorder sometime during their lifetime (5). Approximately 50% of individuals with a history of alcohol abuse or dependence have a mental disorder in their lifetime (1–4).

The co-occurrence of psychiatric and substance use disorders has been associated with an increased likelihood of service utilization; a higher prevalence of comorbidity was found in treatment settings than in the general population (1, 7, 8). However, less is known about whether predictors of service use for persons with comorbid disorders differ from those for persons with a single disorder. Previous research on help seeking has focused primarily on the association between the overall use of services and any psychiatric disorder (9, 10) or the association between a specific type of service use and one or more psychiatric diagnoses (11, 12). Most research has not taken into account the influence of other co-occurring disorders on service utilization and the heterogeneity of different types of disorder.

To shed new light on the influence of co-occurring disorders on utilization of services, we investigated determinants of service utilization among adults with different configurations of psychiatric disorders. Specifically, we examined factors affecting use of mental health and/or substance abuse services in the past year by adults with an alcohol disorder, adults with comorbid alcohol and mental disorders, and adults with psychiatric disorders other than alcohol abuse or dependence. The study sought to address three questions. First, is the use of services different for adults with different diagnostic configurations? Second, what factors are related to the use of services for adults with different diagnoses? Finally, are these factors the same across different diagnostic groups?

METHOD

Data for this analysis were drawn from the National Comorbidity Survey, which consisted of a structured psychiatric interview of a representative national sample of 8,098 residents in the United States. Persons aged 15–54 years were selected from the noninstitutionalized civilian population in the 48 coterminous United States and a representative supplemental sample of students living in campus group housing (5) Of all individuals contacted for participation in the survey, 82% completed the survey assessment. The survey used a two-stage design. In part II, the use of mental health services by a subsample of 5,877 respondents was assessed. These 5,877 respondents included those who had any lifetime diagnosis according to the part I assessment, all persons in the age range of 15–24 years, and a random subsample of the remaining part I respondents. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant after the survey had been fully explained. A detailed description of the National Comorbidity Survey design has been presented elsewhere (5). For the present investigation, the statistical analysis was based on data from part II adult respondents aged 18–54 years (N=5,393); data from youths aged 15–17 years were excluded. This allowed us to examine mental health service utilization by the adult respondents in the National Comorbidity Survey.

Measures

The National Comorbidity Survey used a modified version of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (13) to generate psychiatric diagnoses based on DSM-III-R. The modified version was developed at the University of Michigan for the survey (14). The diagnostic criteria for alcohol abuse/dependence and other psychiatric disorders were consistent with those in a previous report from the National Comorbidity Survey (5).

Utilization of mental health and substance abuse services was defined as any visit to mental health care providers, specialty substance abuse care providers, general medical care providers, human service agencies, or self-help groups for mental health problems, alcohol use, and/or drug use in the past year as reported by the respondents.

Respondents were categorized into five groups according to the nature of their psychiatric disorders. 1) The group with pure alcohol disorder (N=276) included adults who had met the criteria for alcohol abuse or dependence, but not other psychiatric disorders, in the past year. 2) The group with comorbid alcohol and mental disorders (N=267) included adults who had met the criteria for both alcohol abuse/dependence and at least one other psychiatric disorder in the past year. These disorders included major depression, dysthymia, mania, bipolar disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, simple phobia, social phobia, agoraphobia, posttraumatic stress disorder, drug abuse/dependence, and nonaffective psychosis. 3) Respondents who met the criteria for at least one of the other psychiatric diagnoses and who did not meet criteria for alcohol abuse or dependence in the past year constituted the group with other psychiatric disorders (N=1,110). 4) Respondents who met the criteria for any psychiatric disorder in their lifetime but not in the past year were included in the lifetime group (N=1,216). 5) The group with no psychiatric disorder (N=2,524) included adults who had never met the criteria for any DSM-III-R diagnosis in their lifetime.

Alcohol-related symptoms

Alcohol-related symptoms were assessed and defined by items from the Alcohol section of the modified Composite International Diagnostic Interview, which elicited information on the respondent’s use of alcohol, with a focus on the amount, frequency, and consequences of alcohol use. These symptoms included the amount of alcohol drinking, alcohol-related social or occupational impairments, alcohol-related health or psychological problems, and the number of alcohol dependence symptoms. Alcohol drinking was assessed by asking respondents about the number of alcoholic drinks consumed in a single day in the past year. Alcohol-related social or occupational impairments were assessed by five items. Alcohol-related health or psychological problems were assessed by asking the respondent whether alcohol use caused health, emotional, or psychological problems (two items). The number of alcohol dependence symptoms was measured by 10 items.

Sociodemographic variables

These variables included age (in years), sex, education (in years), race/ethnicity, marital status, household income (in dollars), employment status (currently working for pay versus not working for pay), and insurance coverage (none, Medicaid, private insurance).

Social and psychological factors

Social support, conflicted support networks, self-medication, recent stressful life events, and parental history of psychopathology were included. Social support was assessed by asking the respondents about positive characteristics of their social support network (spouse, relatives, or friends) (20 items). Conflicted support networks were measured by asking respondents about negative aspects of the support network (18 items). Self-medication was defined as ever having drunk more than usual or having used drugs not prescribed by a physician (or in greater amounts than prescribed by a physician) to help reduce psychiatric symptoms (e.g., fears, anxiety, sadness, manic feeling, or panic attacks). Recent stressful life events included legal problems, loss events, and relationship problems that had occurred in the year before assessment. Legal problems were defined as having been sued by someone, ever having sued someone, or ever having had trouble with the law enforcement system. Loss events were defined as recently experiencing the death of a close friend or a relative. Relationship problems were defined as having a broken close relationship, a long separation from a loved one, or tension or conflicts with friends or family members. Information on whether the respondent’s natural father or mother had ever been hospitalized or treated for depression, anxiety, or alcohol/drug problems was also collected.

Data Analysis

Bivariate analyses were conducted to examine whether there were significant differences in the patterns of utilization of mental health and substance abuse services and in sociodemographic characteristics among the study groups, and what factors were related to the differences in service utilization. To constrain suspected confounding influences of other sociodemographic factors on service utilization, we conducted multiple logistic regression analyses. For testing whether each individual regression coefficient was equal to zero, p values equal to or less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The results of Wald chi-square tests for main effects in the model are reported. Because of the complex sample design and weighting of the National Comorbidity Survey, SUDAAN software (15) (i.e., CROSSTAB and LOGISTIC procedures) was used to conduct the analyses. SUDAAN uses Taylor series linearization (16) for the computation of standard errors.

RESULTS

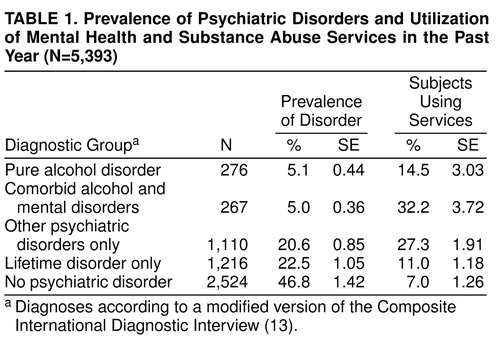

About 47% of the adults had never experienced a psychiatric disorder in their lifetime (Table 1). One-year prevalence rates ranged from 5% to nearly 21% for those with an alcohol disorder only, those with an alcohol disorder and a comorbid psychiatric disorder, and those with non-alcohol-related psychiatric disorders. Almost 23% of the respondents had had a psychiatric disorder in their lifetime. These estimates differ from previous National Comorbidity Survey reports (5) owing to the exclusion of data on persons younger than 18 years of age in our analysis. The rates of service utilization by our four groups with disorders ranged from 7% to 32% (χ2=93.13, df=4, p<0.01). Because disorders over one’s lifetime were difficult to compare with rates of service utilization in 1 year, persons with only a psychiatric disorder in their lifetime (N=1,216) were dropped from subsequent analyses, resulting in a sample of 4,177 respondents. The likelihood of service utilization was significantly different for the four remaining diagnostic groups (χ2=20.51, df=2, p<0.01).

When the sociodemographic characteristics of the four study groups were examined, we found statistically significant differences in age, sex, education, race/ethnicity, and marital status among them (Table 2). These factors have also been found to influence the utilization of mental health services (9, 10, 17).

Bivariate analysis was conducted to estimate the association between each factor examined and service utilization. For persons with an alcohol disorder only, no factors increased the likelihood of using mental health services. For persons with comorbid alcohol disorders, having legal problems in the past year increased the likelihood of reporting use of services (χ2=11.24, df=1, p<0.05). Among persons with nonalcohol disorders, those aged 18–26 years and those who reported having one or two alcohol dependence symptoms were less likely to have used services in the past year (χ2=25.74, df=3, p<0.05, and χ2=12.66, df=1, p<0.05, respectively). Among adults who had never met criteria for any psychiatric disorder, having private insurance coverage was associated with increased service utilization (χ2=14.31, df=1, p<0.05).

We also sought to determine whether the likelihood of service utilization varied by different diagnostic configurations. As can been seen in Table 3, statistical adjustment for the other variables examined in this study did not produce a strong impact on the odds ratio estimates. Among the four diagnostic groups, having no disorder was associated with a decreased likelihood of using services in comparison with having other, non-alcohol-related disorders.

Because the group with only nonalcohol disorders consisted of adults with one or more psychiatric disorders, we divided this group into pure and comorbid categories in order to determine whether having two or more disorders was associated with increased likelihood of service utilization. We did not find a difference in the likelihood of service utilization between respondents having an alcohol disorder only and those having a single non-alcohol-related disorder. In contrast, both comorbid disorder groups (i.e., respondents who had an alcohol disorder with at least one non-alcohol-related disorder and those who had a non-alcohol-related disorder with at least one other non-alcohol-related disorder) were associated with increased relative odds of service utilization as compared with those who had an alcohol disorder only. No significant difference was observed between the two groups with comorbid disorders.

Predictors of Service Utilization

The suspected determinants of service utilization by the four diagnostic groups were also assessed. Adjusted odds ratios were obtained by conducting a multiple logistic regression separately for each diagnostic group while statistically adjusting for the influence of sociodemographic factors.

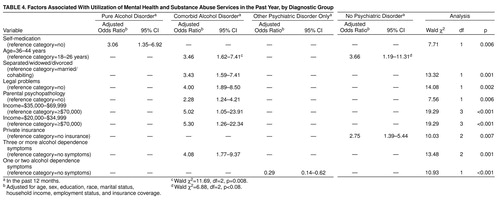

Pure alcohol disorder

Only having a history of self-medication increased the likelihood of service utilization in this group. Persons who had ever used alcohol or drugs to self-medicate their psychological problems were three times more likely to have used services in the past year than those who had not (Table 4).

Comorbid alcohol and mental disorders

Being aged 36–44 years, being separated, widowed, or divorced, having legal problems recently, having a parent with a history of psychopathology, having a household income of $35,000–$69,999 or $20,000–$34,999, and having at least three alcohol dependence symptoms were associated with an increased likelihood of service utilization (Table 4).

Psychiatric disorders other than alcohol disorders

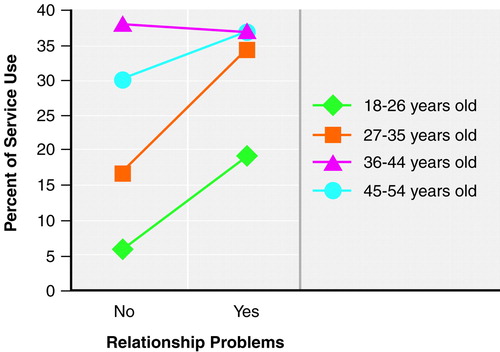

The number of alcohol dependence symptoms was found to have a significant independent effect on mental health service utilization among persons with non-alcohol-related psychiatric disorders. Persons who reported having no alcohol dependence symptoms were about three times (reciprocal of the odds ratio 0.29) more likely to use services than persons who reported having one or two dependence symptoms. A significant interaction term between relationship problems and age was detected. Experiencing a relationship problem increased the likelihood of service utilization among respondents aged 18–35 years (Figure 1).

No psychiatric disorder

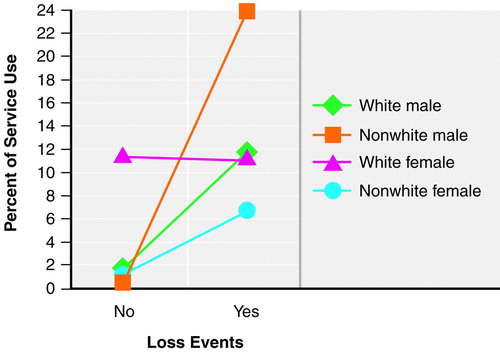

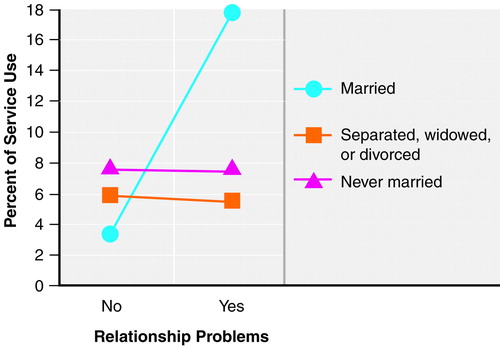

Being aged 36–44 years, relative to being aged 18–26 years, and having private insurance coverage predicted an increased likelihood of service utilization (Table 4). Also, significant interaction terms for loss events and sex, for loss events and race, and for relationship problems and marital status were detected. Recent loss events were associated with an increased likelihood of service use among men and nonwhite women. Experiencing a relationship problem increased the likelihood of service use among the married respondents but not the unmarried respondents. Specifically, 11% of white women used services regardless of whether there were recent loss events; in contrast, recent loss events were associated with increased use of services by men and by nonwhite women (Figure 2). Approximately 18% of married adults with a relationship problem used services as compared with 3% of married adults without a relationship problem (Figure 3).

DISCUSSION

We sought to determine whether the use of services differed among persons with different diagnostic configurations and whether predictors of service utilization were the same across the different diagnostic groups. Our results show that having a comorbid alcohol or nonalcohol disorder was associated with an increased likelihood of service utilization as compared with having an alcohol disorder only. Consistent with previous reports (18–20), the majority of the adults with a psychiatric or alcohol disorder in the past year did not seek help, indicating a need to investigate barriers to help seeking for persons in need of treatment. However, we did not find differences in the likelihood of service utilization between persons having only an alcohol disorder and persons having only a nonalcohol disorder, nor between those having comorbid alcohol disorders and those having comorbid non-alcohol-related disorders. Our findings indicate that persons having comorbid disorders are more likely to be in treatment than persons with a single disorder.

Only being aged 36–44 years was associated with service utilization in more than one diagnostic group. This is consistent with the findings of Ross (4), who reported that adults aged 25–44 years were at the highest risk for having a comorbid alcohol disorder. Developmental transitions associated with changes in employment status or family relationship might have some influence on one’s vulnerability at this stage of the life cycle.

We suspect that a history of self-medication, legal problems, and parental psychopathology may reflect the severity of a person’s psychiatric condition. For instance, use of alcohol and/or drugs to alleviate psychiatric symptoms indicates a need for medication and is likely to depend on one’s mental health. Legal problems were most common in the group with a comorbid alcohol disorder (19%) and least common in the group without a psychiatric disorder (2%).

Similarly, having at least three symptoms of alcohol dependence predicted service use by persons with a comorbid alcohol disorder. There was an unexpected finding for the group that had non-alcohol-related disorders only: having alcohol dependence symptoms was associated with a decreased likelihood of service utilization. This result suggests that persons with non-alcohol-related disorders may use alcohol to self-medicate their psychiatric symptoms (6, 21), and the use of alcohol decreases the likelihood of service utilization.

Contrary to previous reports (9, 11, 17), we did not find sex differences in service utilization in the groups with pure, comorbid, and other diagnoses. When we examined whether women with an alcohol use disorder were greater users of services than men with an alcohol use disorder, no difference was observed. However, when we combined pure, comorbid, and other diagnostic groups into a single diagnostic category, we found that women were about 1.4 times (95% CI=1.04–1.90) more likely to seek help than men regardless of statistical adjustment for other sociodemographic variables. Additional analyses indicated that women in the group with comorbid alcohol use disorder and the group with psychiatric disorders other than alcohol use were more likely to use services than women in the group with no psychiatric disorder. No difference in service utilization was found between the group with comorbid alcohol use disorder and the group with other psychiatric disorders. Among asymptomatic adults, significant interactions between loss events and sex and between loss events and race/ethnicity were detected. Specifically, white women were greater users of services irrespective of a recent loss event (Figure 2), whereas experiencing loss events increased the likelihood of service use among nonwhite women and men.

Among persons without a psychiatric disorder, those aged 36–44 years and those having private health insurance were more likely to use mental health services. Possible limitations associated with the use of a cross-sectional study design (e.g., recall bias and reporting errors) or the survey’s assessment tool may have influenced the identification of psychiatric disturbances among these persons. Such persons may have been at an early stage in the natural history of a disorder and may not have crossed diagnostic thresholds, or they may have had an unidentified psychiatric syndrome or a disorder not assessed by the modified Composite International Diagnostic Interview (22).

Our subsample of service users does not allow us to make more detailed statistical comparisons of determinants of service utilization between the general medical care and specialty mental health care sectors. Replication of our findings by means of a prospective analysis with sufficient numbers of persons in the service sectors should be attempted. An oversampling of racial and ethnic minority groups might provide sufficient numbers of service users with an alcohol disorder in each minority group.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was based on information collected by the National Comorbidity Survey, a collaborative epidemiologic investigation of the prevalence, causes, and consequences of psychiatric morbidity and comorbidity in the United States that is supported by grant MH-46376 from the U.S. Alcohol Drug Abuse and Mental Health Administration and supplemental grant 90135190 from the W.T. Grant Foundation. Ronald C. Kessler is the Principal Investigator. Collaborating National Comorbidity Survey sites and investigators are the Addiction Research Foundation (Robin Room), Duke University Medical Center (Dan Blazer, Marvin Swartz), Harvard Medical School (Ronald C. Kessler), Johns Hopkins University (James Anthony, William Eaton, Philip Leaf), the Max Planck Institute of Psychiatry (Hans-Ulrich Wittchen), the Medical College of Virginia (Kenneth Kendler), the University of Michigan (Lloyd Johnston), New York University (Patrick Shrout), the State University of New York at Stony Brook (Evelyn Bromet), the University of Miami (R. Jay Turner), and Washington University School of Medicine (Linda Cottler).

Received Sept. 10, 1998; revision received Jan. 8, 1999; accepted Feb. 8, 1999. From the Departmental of Mental Hygiene, School of Hygiene and Public Health, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore; and the Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, Baltimore. Reprints of this article are not available. Address correspondence to Dr. Wu, Health and Social Policy Division, Research Triangle Institute, P.O. Box 12194, Research Triangle Park, NC 27709-2194 Supported in part by NIMH training grant T32MH-14592 to Dr. W. Eaton.

|

|

|

|

FIGURE 1. Utilization of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services for Relationship Problems by Subjects With Only a Psychiatric Disorder Other Than an Alcohol-Related Disorder, by Age Group

FIGURE 2. Utilization of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services for Loss Events by Subjects With No Psychiatric Disorder, by Race and Sex

FIGURE 3. Utilization of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services for Relationship Problems by Subjects With No Psychiatric Disorder, by Marital Status

1. Regier DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS, Locke BZ, Keith SJ, Judd LL, Good FK: Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse: results from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) study. JAMA 1990; 264:2511–2518Google Scholar

2. Kessler RC, Crum RM, Warner LA, Nelson CB, Schulenberg J, Anthony JC: Lifetime co-occurrence of DSM-III-R alcohol abuse and dependence with other psychiatric disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1997; 54:313–321Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Kessler RC, Nelson CB, McGonagle KA, Edlund MJ, Frank RG, Leaf PJ: The epidemiology of co-occurring addictive and mental disorders: implications for prevention and service utilization. Am J Orthopsychiatry 1996; 66:17–31Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Ross HE: DSM-III-R alcohol abuse and dependence and psychiatric comorbidity in Ontario: results from the Mental Health Supplement to the Ontario Health Survey. Drug Alcohol Depend 1995; 39:111–128Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, Wittchen H-U, Kendler KS: Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:8–19Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Grant BF, Harford TC: Comorbidity between DSM-IV alcohol use disorders and major depression: results of a national survey. Drug Alcohol Depend 1995; 39:197–206Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Helzer JE, Pryzbeck TR: The co-occurrence of alcoholism with other psychiatric disorders in the general population and its impact on treatment. J Stud Alcohol 1988; 49:219–224Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. du Fort GG, Newman SC, Bland RC: Psychiatric comorbidity and treatment seeking: sources of selection bias in the study of clinical populations. J Nerv Ment Dis 1993; 181:467–474Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Lin E, Goering P, Offord DR, Campbell D, Boyle MH: The use of mental health services in Ontario: epidemiologic findings. Can J Psychiatry 1996; 41:572–577Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Landerman LR, Burns BJ, Swartz MS, Wagner HR, George LK: The relationship between insurance coverage and psychiatric disorder in predicting use of mental health services. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:1785–1790Google Scholar

11. Wells KB, Manning WG, Duan N, Newhouse JP, Ware JE: Sociodemographic factors and the use of outpatient mental health services. Med Care 1986; 24:75–85Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Horgan CM: The demand for ambulatory mental health services from specialty providers. Health Serv Res 1986; 21:291–319Medline, Google Scholar

13. World Health Organization: Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI), Version 1.0. Geneva, WHO, 1990Google Scholar

14. Wittchen H-U, Zhao S, Abelson JM, Abelson JL, Kessler RC: Reliability and procedural validity of UM-CIDI DSM-III-R phobic disorders. Psychol Med 1996; 26:1169–1177Google Scholar

15. Shah BV, Barnwell BG, Bieler GS: SUDAAN Software for the Statistical Analysis of Correlated Data. Research Triangle Park, NC, Research Triangle Institute, 1996Google Scholar

16. Woodruff RS, Causey BD: Computerized method for approximating the variance of a complicated estimate. J Am Statistical Assoc 1976; 71:315–321Crossref, Google Scholar

17. Leaf PJ, Livingston MM, Tischler GL, Weissman MM, Holzer CE, Meyers JK: Contact with health professionals for the treatment of psychiatric and emotional problems. Med Care 1985; 23:1322–1337Google Scholar

18. Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism: Alcohol and Health: Third Special Report to the Congress: DHEW publication ADM 79-832. Washington, DC, US Government Printing Office, 1979Google Scholar

19. Regier DA, Narrow WE, Rae DS, Manderscheid RW, Locke BZ, Goodwin FK: The de facto US mental and addictive disorders service system. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993; 50:85–94Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Robins LN, Locke BZ, Regier DA: Overview: psychiatric disorders in America, in Psychiatric Disorders in America. Edited by Robins LN, Regier DA. New York, Free Press, 1991Google Scholar

21. O’Sullivan K: Depression and its treatment in alcoholics: a review. Can J Psychiatry 1984; 29:379–384Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Marino S, Gallo JJ, Ford D, Anthony JC: Filters on the pathway to mental health care, I: incident mental disorders. Psychol Med 1995; 25:1135–1148Google Scholar