Characteristics of Psychiatrists Who Perform ECT

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Use of ECT is highly variable, and previous study has linked its availability to the geographic concentration of psychiatrists. However, less than 8% of all U.S. psychiatrists provide ECT. The authors analyzed the characteristics of psychiatrists who use ECT to understand more fully the variation in its use and how changes in the psychiatric workforce may affect its availability. METHOD: Data from the 1988–1989 Professional Activities Survey were examined to investigate the influence of demographic, training, clinical practice, and geographic characteristics on whether psychiatrists use ECT. RESULTS: Psychiatrists who provided ECT were more likely to be male, to have graduated from a medical school outside the United States, and to have been trained in the 1960s or 1980s rather than the 1970s. They were more likely to provide medications than psychotherapy, to practice at private rather than state and county public hospitals, to treat patients with affective and organic disorders, and to practice in a county containing an academic medical center. CONCLUSIONS: Demographic and training characteristics significantly influence whether a psychiatrist uses ECT. Opposing trends in the U.S. psychiatric workforce could affect the availability of the procedure. Expanding training opportunities for ECT and making education, training, and testing more consistent nationwide could improve clinicians' consensus about ECT and narrow variation in its use. (Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:889–894)

ECT is an important psychiatric treatment, particularly for severe or refractory major depression (1, 2). Data from states and localities suggest that after increasing during the 1940s and 1950s, use of ECT declined over the following decades (3–6). In analyses of national hospital survey data, Thompson et al. (7) found that use of ECT decreased 46% between 1975 and 1980 but that it did not significantly change between 1980 and 1986. The authors concluded that the decline in use of ECT in the United States ended in the 1980s. A subsequent analysis of Medicare claims (8) found that use of ECT began to rise again in the early 1990s among the nation's elderly and Medicare-eligible disabled.

Trends in aggregate annual ECT use do not adequately reveal the underlying variation. The prevalence of major depression (the principal disorder treated with ECT) has been shown to be consistent across geographic areas (9). However, per capita utilization rates of ECT vary widely across the United States. A study of ECT use in 317 U.S. cities (10), based on survey data, found no use of ECT in one-third of cities. Among the cities where its use was reported, the rate in the city with the greatest use was more than fivefold higher than the rate in the city with the least use. Such patterns of use suggest a lack of access to the procedure in some areas and a lack of uniformity in its administration (11).

The variation study found that one of the most influential predictors of the amount of ECT administered was an area's supply of psychiatrists. It is well-known that psychiatrists are unevenly distributed across the United States; for example, states vary more than eightfold in the number of psychiatrists per capita (12). Overall psychiatrist supply provides only a partial explanation, however, because a very small proportion of psychiatrists (less than 8% [13]) use ECT. In this report, we analyze the characteristics of psychiatrists who make use of ECT, in order to provide a fuller understanding of variation in its use. We also consider how changes in the psychiatric workforce may affect the availability of ECT.

A literature search that used MEDLINE and other sources found little information about the characteristics of psychiatrists who provide ECT. A survey of a sample of members of the American Psychiatric Association (APA) conducted in the late 1970s (14) found that compared with nonusers, ECT users were more likely to be male, to practice in psychiatric hospitals, to work in large or medium-sized cities, and to characterize their orientation as “organic” or “eclectic.” Milstein and Small (15) administered the same survey to Indiana psychiatrists in 1982, with similar findings, except that psychiatrists who provided ECT were more likely to be board-certified in psychiatry. Several studies have examined attitudes of psychiatrists toward ECT and found marked disagreement among clinicians regarding the value of the procedure (16–19). Using data from the 1988–1989 APA Professional Activities Survey, Koran (13) found that psychiatrists who used ECT reported treating greater numbers of patients, spending more hours in hospitals and in patient care, and treating more patients with affective disorders. Our study expands on these bivariate analyses by examining Professional Activities Survey data with multivariate techniques and by exploring a wider array of demographic, training, clinical practice, and geographic characteristics.

METHOD

The data on ECT use were drawn from the 1988–1989 APA Professional Activities Survey. The survey questioned respondents about their demographic characteristics, training, clinical practice activities, caseload, and work setting. The survey methods are described in more detail elsewhere (20). The survey was sent to 34,164 psychiatrist members of APA and the 10,091 nonmember psychiatrists identified from the American Medical Association's Physician Masterfile. The response rate was 67.7% for APA members and 28.9% for nonmembers. Of 26,045 respondents, the final sample consisted of 14,285 psychiatrists living in the United States who 1) were not retired, residents, or fellows, 2) were actively treating patients, and 3) fully completed the survey. There were no significant differences between respondents and nonrespondents on available indexes such as age and gender. Nor were there differences between respondents who fully completed the survey and partial responders on these or other indexes, including caseload characteristics.

The dependent variable for the analysis was whether or not a psychiatrist administered ECT. The Professional Activities Survey asked each respondent whether he or she had administered ECT in the past month.

Potential determinants of whether a psychiatrist used ECT (independent variables) included demographic and training characteristics, clinical orientation, factors related to clinical work, and geographic area characteristics.

A literature review found no published reports of differences in psychiatrists' use of ECT by gender or race. Studies of gender differences in physician practice have found that men are more likely than women to train in procedure-oriented specialties, and within the same specialty they are more likely to use invasive procedures (21, 22). Accordingly, we hypothesized that male psychiatrists would be more likely to use ECT.

Few empirical data have been collected on education and training in ECT in American medical schools and psychiatric residency programs. Fink (23) noted that only a limited number of training programs teach physicians ECT administration and observed that the subject was particularly neglected by residencies between 1960 and 1980. Thus, we hypothesized that psychiatrists trained in these two decades would be less likely to administer ECT than psychiatrists trained during other periods. Psychiatrists were divided into cohorts based on the decade of completion of psychiatric residency training. We also examined whether psychiatrists who graduated from a medical school outside the United States were more or less likely to use ECT. International medical graduates could differ in clinical practices because of differences in their clinical training. However, the association between training and practice could be affected by differences in practice setting or patient case mix as well; thus, our model controlled for some work setting and caseload characteristics. A review of the literature found no studies of differences in the practices of U.S. psychiatrists based on education within or outside the United States.

Much attention has been given in recent years to the undertreatment of depression in the elderly and the usefulness of ECT for depressed elderly patients (24, 25). Thus, we hypothesized that psychiatrists who completed a geriatric psychiatry fellowship would be more likely to use ECT.

To examine the influence of psychiatrists' clinical orientation on whether they provided ECT, we classified respondents' clinical practice as primarily psychotherapy-oriented, psychopharmacologically oriented, or mixed, on the basis of self-reports of customary clinical services they provide. Because ECT and pharmacologic interventions are both based on biology, we expected that psychiatrists with a psychopharmacologically oriented practice would be more likely to administer ECT than psychiatrists with a mixed or psychotherapy-oriented practice.

Several control variables were included in the analysis, reflecting clinical, work setting, and geographic characteristics known to be related to differential patterns of ECT use. We controlled for differences in psychiatrists' caseloads by diagnostic category and for the percentage of psychiatrists' work hours devoted to patient care. Because ECT is more commonly used at private rather than public hospitals (7, 26), we controlled for hospital type among hospital-based psychiatrists. Reports suggest that ECT use is more common in academic medical centers than in other practice settings (3). In the absence of direct information on psychiatrists' academic affiliation, we included a proxy measure: whether there was an academic medical center in the psychiatrist's county of practice. To control for geographic differences in ECT use, we included the psychiatrist's census region and a measure of the urbanicity of the psychiatrist's county of practice. Data on academic medical centers and population density were obtained from the Department of Commerce Area Resource File (27).

In the statistical analysis, we first used univariate tests to determine the significance of differences in the independent variables between the psychiatrists who did and did not use ECT. Chi-square tests and t tests were used to examine differences in proportions and means, respectively. Because of the large number of comparisons made, we chose a conservative cutoff level for type I error (p≤0.01) to determine significance.

We then estimated a multiple regression model of the probability that the psychiatrist would provide ECT, testing the significance of each independent variable while controlling simultaneously for all of the other factors hypothesized above to be significant predictors of ECT use. Because our dependent variable was dichotomous, logistic regression was used for the analysis. Likelihood ratio tests of the joint significance of multiple indicators corresponding to a single categorical variable are reported in addition to the tests of the individual significance of each regressor.

To facilitate interpretation of the logit estimates, we report the odds ratio and 99% confidence interval associated with each regressor. For dichotomous regressors, the odds ratio approximates the probability that the psychiatrist uses ECT when the regressor is set equal to 1, divided by the probability when the regressor is set equal to 0. For continuous regressors, we calculated the odds ratio as an approximation of the probability of ECT use when the regressor is set equal to the mean plus 1 SD, divided by the probability when it is set equal to the mean only.

RESULTS

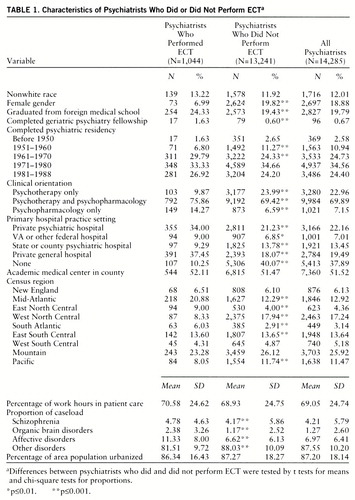

Descriptive statistics are reported in table 1. Of 14,285 psychiatrists in our sample, 1,044 (7.3%) reported providing ECT. Unadjusted differences between psychiatrists based on whether or not they provided ECT are presented.

Results from the logistic regression are reported in table 2. Among the demographic variables, female psychiatrists were much less likely to use ECT than male psychiatrists. No differences by race/ethnicity in psychiatrists' use of ECT were seen.

Training characteristics were significantly associated with differences in the use of ECT. The indicators for year of completion of residency were jointly significant (χ2=25.00, df=4, p≤0.0001), and for the later years, individually significant as well. Compared with psychiatrists who completed their residency between 1971 and 1980, psychiatrists educated between 1961 and 1970 and between 1981 and 1988 were more likely to use ECT. Psychiatrists who graduated from a medical school outside the United States were more likely than graduates of U.S. medical schools to provide ECT. Psychiatrists who completed a geriatric psychiatry fellowship were more likely to use ECT than those who did not, but the difference was only marginally significant at the 0.01 level.

Indicators of clinical orientation were strongly associated with use of ECT, both jointly (χ2=61.48, df=2, p≤0.0001) and individually. Compared with psychiatrists who used both psychotherapy and psychopharmacology, psychiatrists who used psychotherapy only were less likely to administer ECT, while psychiatrists who used psychopharmacology only were more likely to use ECT.

The indicators for hospital type were also jointly significant predictors of ECT use (χ2=331.14, df=4, p≤0.0001). Compared with psychiatrists whose primary inpatient work setting was a private psychiatric hospital, psychiatrists who worked at state or county public hospitals were less likely to use ECT. Differences between psychiatrists at private psychiatric hospitals and those at federal public hospitals were not individually significant. No significant difference between specialty and general hospitals was found.

There were significant differences based on psychiatrists' caseload, both jointly (χ2=250.71, df=3, p≤0.0001) and in some instances individually. Caseloads of psychiatrists who used ECT included a higher proportion of patients with affective disorders and organic disorders than patients with other psychiatric disorders. The finding of higher rates of affective disorders is consistent with studies demonstrating the efficacy of ECT for major depression and bipolar disorder. Higher rates of organic disorders were unexpected and may reflect high rates of comorbidity between depression and dementia in the elderly.

Differences based on census regions were jointly significant (χ2=121.67, df=8, p≤0.0001). Among U.S. census regions, psychiatrists in the South Atlantic region (West Virginia, Florida, Georgia, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Delaware, and Maryland), the Mid-Atlantic region (New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania), and the Southeast Central region (Kentucky, Tennessee, Alabama, and Mississippi) were more likely to perform ECT than psychiatrists in New England. Psychiatrists in the Northeast Central region (Michigan, Illinois, Ohio, Wisconsin, and Indiana) were less likely to perform ECT than psychiatrists in New England. Psychiatrists with an academic medical center in their county were more likely to provide ECT. No difference in the urbanicity of counties of practice was found.

DISCUSSION

These findings provide new information regarding characteristics of psychiatrists who use ECT. Controlling for several potentially confounding factors (psychiatrists' work hours, decade of training, case~load, and work setting), we found that female psychiatrists were only one-third as likely to administer ECT as male psychiatrists. Reasons for the difference between the genders in ECT use are not known, but possibilities include differences in attitudes toward ECT and/or differences in training and job opportunities available to women. Although several studies have examined psychiatrists' attitudes toward ECT, none has looked at differences by gender. A 1993 APA report on the gap between men's and women's participation in academic psychiatry (28) concluded that socialization, subtle discrimination, and family responsibilities may play a role. These factors could contribute to the gender gap seen in ECT use. An important implication of these findings can be observed in the shifting demographics of the psychiatric workforce. The proportion of women among new psychiatrists has been steadily rising, reaching 43% in 1990. If the gap between genders in ECT use continues, this trend may exacerbate the variability in the availability of the treatment. Further study should investigate reasons for this gap and consider appropriate responses.

Training characteristics also were influential in psychiatrists' use of ECT. Psychiatrists who graduated from medical school outside the United States were more likely to use ECT than graduates from U.S. schools. This result may partially reflect unmeasured differences among psychiatrists' caseloads and work settings, but it could also reflect differences in training, clinical orientation, and job opportunities between foreign medical graduates and graduates of U.S. medical schools. These findings also carry implications for the future availability of ECT. In 1997, a broad coalition of health care organizations proposed changes to funding and immigration status that would limit the numbers of international medical graduates training and practicing in the United States. Such measures would have a considerable impact on the supply of U.S. psychiatrists and over time could have an adverse impact on the number of psychiatrists using ECT.

A countervailing trend may serve to increase the supply of psychiatrists providing ECT. Psychiatrists trained in the 1970s were less likely than psychiatrists trained in other decades to use ECT. This suggests that the training deficit cited by Fink (23) and others during this period may have been greatest during the 1970s and been followed by increased attention to ECT by training programs in the 1980s. Such a trend would be consistent with an increasing emphasis on biological treatments and evidence that ECT use may be on the rise.

Although psychiatrists who completed specialty training in geriatric psychiatry were more likely to administer ECT than nonspecialists, this finding was only marginally significant, in part because of the small number of geriatrics-trained psychiatrists in our sample (N=96). In recent years, researchers and educators have focused increased attention on depression in geriatric patients and on findings which suggest that ECT can play an important role in the treatment of this population. The 1992 National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Panel report “Diagnosis and Treatment of Depression in Late Life” (24) concluded that ECT is an effective treatment for depression in the elderly “but is generally underused or unavailable.” Our results suggest that as the number of psychiatrists completing geriatric psychiatry fellowships increases, the use and availability of ECT may increase as well.

Our findings also confirm previous findings regarding ECT use. Psychiatrists who provided ECT were more likely to work at private hospitals than at public institutions and to treat patients with affective disorders rather than those with other conditions. Geographic variation in psychiatrists' use of ECT was seen among large census regions.

Our analysis is subject to certain limitations. The Professional Activities Survey was conducted in 1988–1989. Although it is the most recent national survey of psychiatrists' practices, changes in practice may have occurred since these data were collected. The data are self-reported, with the possibility of recall bias. The survey only asked psychiatrists about use of ECT in the previous month; characteristics of psychiatrists who provided ECT only occasionally or not at all during the period surveyed may not be well represented in the results. The Professional Activities Survey focused on practicing psychiatrists who completed training; thus, characteristics of residents and fellows who used ECT are not included in the results. The response rate of the Professional Activities Survey was low for APA nonmembers, although ECT use did not significantly differ between members and nonmembers.

Other factors, unavailable for inclusion in this analysis, may also influence whether a psychiatrist provides ECT. Examples include characteristics of the psychiatrist's caseload, such as severity of illness and treatment preferences, the residency program in which a psychiatrist trained, and malpractice insurance surcharges for ECT.

We previously reported evidence suggesting that access to ECT is limited in some areas of the United States and that ECT use is strongly associated with the supply of psychiatrists in these areas (10). The present study extends this analysis by evaluating characteristics of psychiatrists who use ECT. However, another group of psychiatrists—not studied in this report—also influence access to the procedure, i.e., psychiatrists who do not themselves administer ECT but nonetheless recommend ECT to their patients and refer them for treatment by others. While attitudes of psychiatrists toward ECT have been studied elsewhere (16–19), their referral practices have not been examined. This component of access requires further attention.

CONCLUSIONS

While ECT is an important and effective treatment for certain psychiatric disorders, its use is highly variable. This study explored the contribution of psychiatrists' characteristics to this variability, finding that gender, training characteristics, and clinical orientation affect psychiatrists' use of ECT. Improving the quality and consistency of ECT training in medical school, residency, postdoctoral fellowships, and psychiatry board examinations would lead to the development of a broader clinical consensus regarding ECT and could narrow variability in its use. Further attention to the association between psychiatrists' gender and use of the modality is warranted, beginning with a survey examining attitudes and opportunities to gain experience with ECT. Trends in the composition of the psychiatry workforce may further affect the availability of ECT and require the attention of mental health care planners and educators.

|

|

Received July 23, 1997; revisions received Nov. 7 and Dec. 29, 1997; accepted Feb. 9, 1998. From the Malcolm Wiener Center for Social Policy, John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass.; the Department of Psychiatry, Cambridge Hospital; and the Department of Health Care Policy, Harvard Medical School, Boston. Address reprint requests to Dr. Hermann, Department of Psychiatry, Cambridge Hospital, 1493 Cambridge St., Cambridge, MA 02139. Supported by NIMH grants MH-01477 (R.C.H.), MH-01177 (R.A.D.), and MH-53698 (S.L.E.). The authors thank Sherrie Epstein for editorial assistance.

1 American Psychiatric Association: Practice Guideline for Major Depressive Disorder in Adults. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150(April suppl)Google Scholar

2 The Practice of Electroconvulsive Therapy: Recommendations for Treatment, Training, and Privileging: A Task Force Report of the American Psychiatric Association. Washington, DC, APA, 1990Google Scholar

3 Fink M: Convulsive Therapy: Theory and Practice. New York, Raven Press, 1979Google Scholar

4 Babigian HM, Guttmacher LB: Epidemiologic considerations in electroconvulsive therapy. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1984; 41:246–253Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5 Morrissey J, Burton N, Steadman H: Developing an empirical base for psycho-legal policy analyses of ECT: a New York State survey. Int J Law Psychiatry 1979; 2:99–111Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6 Mills MJ, Pearsall DT, Yesavage JA, Salzman C: Electroconvulsive therapy in Massachusetts. Am J Psychiatry 1984; 141:534–538Link, Google Scholar

7 Thompson JW, Weiner RD, Myers CP: Use of ECT in the United States in 1975, 1980, and 1986. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:1657–1661Link, Google Scholar

8 Rosenbach ML, Hermann RC, Dorwart RA: Use of electroconvulsive therapy in the Medicare population between 1987 and 1992. Psychiatr Serv 1997; 48:1537–1542Link, Google Scholar

9 Robins LN, Regier DA (eds): Psychiatric Disorders in America: The Epidemiological Catchment Area Study. New York, Free Press, 1991Google Scholar

10 Hermann RC, Dorwart RA, Hoover CW, Brody J: Variation in ECT use in the United States. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:869–875Link, Google Scholar

11 Hermann RC: Variation in psychiatric practices: implications for health care policy and financing. Harvard Rev Psychiatry 1996; 4:98–101Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12 Koran LM: The Nation's Psychiatrists. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1987Google Scholar

13 Koran LM: Electroconvulsive therapy. Psychiatr Serv 1996; 47:23Link, Google Scholar

14 American Psychiatric Association Task Force Report 14: Electroconvulsive Therapy. Washington, DC, APA, 1978Google Scholar

15 Milstein V, Small I: Electroconvulsive therapy: attitudes and experience—a survey of Indiana psychiatrists. Convuls Ther 1985; 1:89–100Medline, Google Scholar

16 Levenson J, Willett A: Milieu reactions to ECT. Psychiatry 1982; 45:298–306Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17 Kalayam B, Steinhart MJ: A survey of attitudes on the use of electroconvulsive therapy. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1981; 32:185–188Abstract, Google Scholar

18 Janicak P, Mask J, Trimakas K, Gibbons R: ECT: an assessment of mental health professionals' knowledge and attitudes. J Clin Psychiatry 1985; 46:262–266Medline, Google Scholar

19 Freeman C, Cheshire K: Review: attitude studies on electroconvulsive therapy. Convuls Ther 1986; 2:31–42Medline, Google Scholar

20 Dorwart RA, Chartock LR, Dial T, Fenton W, Knesper D, Koran LM, Leaf PJ, Pincus H, Smith R, Weissman S, Winkelmeyer R: A national study of psychiatrists' professional activities. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:1499–1505Link, Google Scholar

21 Cohen M, Ferrier B, Woodword C, Goldsmith C: Gender differences in practice patterns of Ontario family physicians. J Am Med Wom Assoc 1991; 46:49–54Medline, Google Scholar

22 Eliason B, Lofton S, Mark D: Influence of demographics and profitability on physician selection of family practice procedures. J Fam Pract 1994; 39:341–347Medline, Google Scholar

23 Fink M: Impact of the antipsychiatry movement on the revival of electroconvulsive therapy in the United States. Psychiatr Clin North Am 1991; 14:793–801Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24 NIH Consensus Development Panel: Diagnosis and treatment of depression in late life. JAMA 1992; 268:1018–1024Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25 Tomac T, Rummans T, Pileggi T, Li H: Safety and efficacy of electroconvulsive therapy in patients over age 85. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 1997; 5:126–130Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26 Kramer BA: Use of ECT in California, 1977–1983. Am J Psychiatry 1985; 142:1190–1192Link, Google Scholar

27 Office of Data Analysis and Management, US Department of Commerce: The ODAM Area Resource File (ARF). Springfield, Va, National Technical Information Service, 1988Google Scholar

28 American Psychiatric Association Committee on Research Training: Women in academic psychiatry and research (official actions). Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:849–851Link, Google Scholar