Dartmouth Assessment of Lifestyle Instrument (DALI): A Substance Use Disorder Screen for People With Severe Mental Illness

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Despite high rates of co-occurring substance use disorder in people with severe mental illness, substance use disorder is often undetected in acute-care psychiatric settings. Because underdetection is related to the failure of traditional screening instruments with this population, the authors developed a new screen for detection of substance use disorder in people with severe mental illness. METHOD: On the basis of criterion (“gold standard”) diagnoses of substance use disorder for 247 patients admitted to a state hospital, the authors used logistic regression to select the best items from 10 current screening instruments and constructed a new instrument. They then tested the validity of the new instrument, compared with other screens, on an independent group of 73 admitted patients. RESULTS: The new screening instrument, the Dartmouth Assessment of Lifestyle Instrument (DALI), is brief, is easy to use, and exhibits high classification accuracy for both alcohol and drug (cannabis and cocaine) use disorders. Receiver operating characteristic curves showed that the DALI functioned significantly better than traditional instruments for both alcohol and drug use disorders. CONCLUSIONS: Initial findings suggest the DALI may be useful for detecting substance use disorder in acutely ill psychiatric patients. Further research is needed to validate the DALI in other settings and with other groups of psychiatric patients. (Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:232–238)

Almost 20% of people in the U.S. population have a substance use disorder at some point in their lives, yet one-half or more of the cases of current substance use disorders go undetected by medical providers (1). Detection of substance use disorder in psychiatric patients is even more critical because of the high rate of comorbidity (approximately 50%) in people with severe disorders, such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder (2–6), and because of the negative consequences of substance abuse in this population (7–11). Nevertheless, substance use disorders frequently go undetected in psychiatric care settings (11–14).

One reason for the frequent underdetection of these disorders in the psychiatric population is the limitations of available approaches. Acutely ill psychiatric patients are frequently unable to complete lengthy structured interviews (15). Many psychiatric patients deny, minimize, or fail to perceive the consequences of substance abuse when responding to interviews (16). For example, Goldfinger et al. (17) found that the substance use disorder section of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R had only 24% sensitivity with a group of homeless mentally ill patients. Medical examinations also have poor detection rates with psychiatric patients, possibly because psychiatric patients who abuse substances often do not have the long histories of heavy drinking that produce medical sequelae (18). The picture with laboratory tests is more mixed. Although these tests yield many false negatives and are ineffective when there are delays between drug use and testing, they often detect current use that is denied by patients (11, 13, 14).

The most common approach to screening for substance use disorder has been the use of brief self-report or interview instruments. A number of these tests have been developed, but they often have poor classification accuracy for specific groups other than the ones with which they have been developed, and few have been carefully tested with psychiatric patients. For example, the Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (MAST) (19), which is reliable and valid as a screening tool for persons with primary alcoholism, has been tested several times with psychiatric patients and found to have poor specificity (36%–89%) (20). Many of the MAST items are irrelevant or confusing for people with severe mental illness (21).

Thus, previous work strongly supports the need for a brief screen for substance use disorder that is specifically tailored for psychiatric patients in acute-care settings. In this paper we describe the development and initial testing of a new screen for the detection of substance use disorder in people with severe mental illness, the Dartmouth Assessment of Lifestyle Instrument (DALI). The DALI focuses on alcohol, cannabis, and cocaine use disorders, which are by far the most common substance use disorders among psychiatric patients (2, 4, 5, 22–24).

METHOD

Overview

We established criterion diagnoses of substance use disorder for patients entering a state hospital by using a structured clinical interview and clinician ratings from the community. The patients were then evaluated by using 10 current screening instruments, and an optimal set of items for detecting alcohol use disorder and drug use disorder was selected by means of logistic regression. The DALI was then validated in a second group of admissions by using receiver operating characteristic curves to compare its classification accuracy with that of other screening instruments.

Study Groups

We evaluated all eligible admissions to New Hampshire Hospital over 2 years between 1994 and 1996. As the only public psychiatric hospital in the state, New Hampshire Hospital receives admissions from all regions of New Hampshire. The eligibility criteria for the study included a diagnosis of severe and persistent mental illness (e.g., schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder, major depression) according to the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID) (25), no organic mental syndrome or disorder, and a 6-month connection with a clinician in the New Hampshire mental health system. The selection procedure for study inclusion was blind to the clients' substance abuse status. A prior connection in the New Hampshire mental health system was necessary to obtain the clinician ratings of substance use disorder used in establishing the criterion diagnosis (to be described). Each patient was enrolled in the study only once, regardless of the number of admissions to New Hampshire Hospital over the course of the study. During the 2-year period, 352 patients met these eligibility criteria, and 320 (90.9%) of the eligible patients provided written informed consent to participate in the study. The first 247 patients admitted became the index study group, and the next 73 patients formed the validation study group.

The index study group of 247 patients had an average age of 38.03 years (SD=8.82); 52.2% were female (N=129), 1.6% were non-Caucasian (four of 246), 84.6% were not married (N=209), and 73.9% had graduated from high school or had equivalent education (176 of 238). Primary psychiatric diagnoses were available for 245 patients; most patients had primary diagnoses of schizophrenia (19.2%, N=47), schizoaffective disorder (24.9%, N=61), bipolar disorder (19.2%, N=47), or major depression (12.7%, N=31); 24.1% of the patients (N=59) had other diagnoses. A group of 73 patients consecutively admitted after the index group constituted the validation study group. These patients were similar to the index group on all demographic and clinical characteristics. Both groups were similar to all patients admitted to this hospital during this period on age, education, ethnicity, and marital status. Approximately one-third of all admitted patients were not eligible for the study because their diagnoses did not qualify as severe mental illness (e.g., personality disorders, adjustment disorder, or acute stress disorder).

Measures

Criterion diagnosis. The criterion, or “gold standard,” diagnosis was based on clinician ratings on the Clinician Rating Scale (3) and an independent diagnosis for current (last 6 months) substance use disorder according to the SCID. Our criterion for alcohol or drug use disorder was a finding of active abuse or dependence in the past 6 months according to either the Clinician Rating Scale or the SCID.

The Clinician Rating Scale addresses the problem of diagnostic sensitivity by reducing the rater's reliance on disclosure through either self-report or interview procedures. Trained clinicians make ratings on this scale on the basis of self-reports, interviews, longitudinal behavioral observations, collateral reports, and all clinical records, including results from medical examinations, psychiatric evaluations, and laboratory tests, over the past 6 months. Separate ratings are made for alcohol and other drugs on 5-point scales: 1=abstinence; 2=use without impairment; 3=abuse (DSM-III-R criteria); 4=dependence (DSM-III-R criteria); and 5=severe dependence (DSM-III-R criteria for dependence plus a recurrent need for institutionalization due to substance use disorder). For the purpose of examining screening devices, we collapsed the five Clinician Rating Scale ratings into two levels: ratings of 1 and 2 indicated nonabuse, and ratings of 3–5 denoted substance use disorder. Clinicians made separate ratings for alcohol, cannabis, and cocaine.

The Clinician Rating Scale is reliable, sensitive, and specific when used by case managers who follow their mentally ill patients over time in the community (3, 8, 26–29). Analyses of interrater reliability, comparing ratings of trained clinical case managers and team psychiatrists, have yielded kappa coefficients between 0.80 and 0.95 for current use disorder (3, 8). Clinician Rating Scale ratings have been validated with psychiatric patients by using other substance abuse measures (3, 26, 28) and measures of motives and expectations for substance abuse (29). Other researchers (2, 16, 17, 30) have also shown that clinician ratings are better for detecting substance use disorder than is self-report.

The SCID (25) is a structured interview that entails specific questions for DSM-III-R criteria. The substance use disorder section addresses alcohol and other drugs separately. For the purpose of this study, interviewers focused the alcohol and drug questions on the 6 months preceding hospitalization so that the time interval coincided with that represented by the Clinician Rating Scale ratings.

Substance use disorder among psychiatric patients is often detected with one mode of assessment but not another, and the discrepancy between any two measures is typically due to nondisclosure on one measure rather than to a false positive on the other (3, 11, 17, 31). For this reason, our criterion diagnosis was defined as the presence of substance use disorder according to either the Clinician Rating Scale or the SCID. Among the total of 118 patients with an alcohol use disorder according to either the Clinician Rating Scale (scores of 3–5) or the SCID, 46 patients (39.0%) were identified by both the Clinician Rating Scale and SCID, 47 patients (39.8%) were identified by only the Clinician Rating Scale, and 25 patients (21.2%) were identified by only the SCID. Among the 69 patients with drug use disorder, 26 (37.7%) were identified by both the Clinician Rating Scale and SCID, 26 (37.7%) were identified by only the Clinician Rating Scale, and 17 (24.6%) were identified by only the SCID. The SCID-only diagnoses were taken as face valid, as already described, but the diagnoses determined by only the Clinician Rating Scale were confirmed by a check of all community records on 15 randomly selected patients. These records contained strong confirmatory evidence. For example, one patient had been hospitalized five times because of alcohol abuse during the 6-month interval but was not given a diagnosis of substance use disorder with the SCID because he denied any use.

Substance use disorder screening instruments. The following widely used screens were administered in their entirety to all participants as part of a comprehensive battery: MAST (19), CAGE (32), T-ACE (33), NET (34), TWEAK (35), Drug Abuse Screening Test (36), and Reasons for Drug Use Screening Test (37). These scales vary in length from three to 31 items, and all have shown good reliability and validity with nonpsychiatric populations. Although these screens are often self-administered, in this study trained interviewers administered the entire battery. This procedure has been recommended by both researchers and clinicians assessing acutely and severely mentally ill persons because problems of attention, motivation, question comprehension, and literacy are likely to interfere with direct self-report procedures (for example, see reference 38). At the study site we had evidence that standard scales, such as the SCL-90-R (39), had much lower completion rates when self-administered than when used in the interviewer-administered format. Some of the scales have overlapping items, and we asked each of the overlapping questions once.

Structured interviews for substance use disorder. We also incorporated portions of the Life-Style Risk Assessment Interview (40), the Alcohol Research Foundation Intake Interview (41), and the Addiction Severity Index (42). The Life-Style Risk Assessment Interview was designed to be nonthreatening and to detect alcohol use disorder in medical settings where patients' presenting complaints are not related to substance use disorder. We incorporated the nine introductory questions from this scale to reduce subject defensiveness. The Alcohol Research Foundation Intake Interview deals with legal and treatment history, alcohol consumption patterns, quantity, social context, beverage preference, recent drug use, and adverse consequences of alcohol use. The Addiction Severity Index sections on drug and alcohol use, family and social relationships, and family history of substance use disorder were also included.

Cognitive function. The Mini-Mental State examination (43) is a brief screen for assessing cognitive functioning. It consists of 11 questions. The maximum score is 30, and a score of less than 23 is generally taken to indicate cognitive impairment.

Procedures

Researchers tracked all admissions to New Hampshire Hospital daily to determine study eligibility. Hospital charts were reviewed to determine probable diagnosis and prior connections with community mental health centers, and staff nurses provided initial estimates of current mental status, ability to provide informed consent, and approachability. Hospital psychologists and trained clinicians, independent from the research interviewers, administered the SCID, including the alcohol and substance use module. Once probable eligibility was determined, the project coordinator contacted potential subjects to explain the nature of the study, to obtain written informed consent, and to administer the Mini-Mental State examination. When appropriate, consent from legal guardians was also obtained.

Trained research interviewers administered the composite substance use disorder interview, which averaged less than 1 hour. Interrater reliability was checked throughout the study on every 10th patient. To simulate usual clinical procedures, the subjects were informed that information gleaned during the interview would be shared with their clinical team at the hospital and treated as part of the clinical record.

Statistical Analyses

When a reliable and valid criterion measure exists, discriminative procedures are preferable to traditional instrument-development techniques (44). Starting with the criterion diagnoses of alcohol use disorder and drug use disorder (cannabis or cocaine), we used standard logistic regression procedures to identify the optimal set of items from the existing screens to form the DALI. We then tested the DALI on an independent group of patients, using receiver operating characteristic curves to compare the DALI with other screens. Receiver operating characteristic procedures allow the comparison of two continuous screening measures with different blends of sensitivity and specificity to determine optimum cutoff points for detection. Receiver operating characteristic curves plot false alarms (1 minus sensitivity) against specificity. The area under the curve provides a comparison of scales (45).

RESULTS

Alcohol Use Disorder Screen

In the index study group of 247 patients, our procedures for establishing a criterion diagnosis identified 96 patients (38.9%) as meeting the DSM-III-R criteria for current (past 6 months) alcohol use disorder (abuse or dependence). Using stepwise logistic regression with the criterion alcohol diagnosis as the dependent variable, we identified the best items (p<0.01) from each of the 10 scales. The individual instruments contained between four and 50 questions each, and the stepwise logistic regression generally yielded between zero and four items per scale, for a total of 28 best items. These 28 items were included in a final stepwise logistic regression that yielded nine items and correctly classified 85.4% (170 of 199) of the patients as to their status on alcohol use disorder.

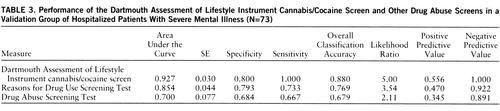

We next compared the DALI screen for alcohol use disorder with traditional instruments by using receiver operating characteristic curves. The standard interview and self-report measures of alcohol use disorder yielded overall classification accuracies varying between 61.1% and 74.1%, with different mixtures of sensitivity and specificity. Curves for the DALI and three of the common measures that performed best are shown in figure 1.

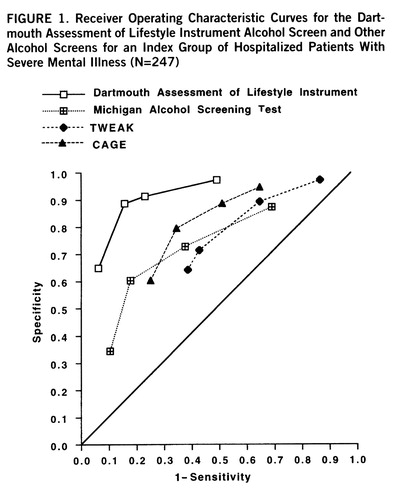

The DALI enjoys an inherent advantage, in comparisons with the existing scales from which it was drawn, in the index group from which it was derived. To eliminate this bias, we next assessed the DALI alcohol items in the validation group of 73 patients, which contained 22 patients (30.1%) with alcohol use disorder. The classification accuracy in the validation group was a comparable 83.1% (49 of 59). Figure 2 shows the performance of the alcohol DALI, in comparison with traditional instruments, in the validation group.

We carried out additional statistical comparisons of the various alcohol scales, using the approximation procedures described by Hanley and McNeil (45, 46). Because the scores on the DALI and the other alcohol scales came from the same patients, we used the corrected formula for the combined standard error described by Hanley and McNeil (46). The corrected formula involves the calculation of r on the basis of the correlation between two separate sets of scores for the abusers and nonabusers and the areas under the two respective curves. The value of that r from the index group was 0.44. Using these procedures, we compared the DALI to all of the other alcohol scales. Pairwise z values appear in table 1.

A number of statistics besides sensitivity, specificity, and overall classification accuracy are commonly used to compare the accuracy of screens, and these include positive predictive value, negative predictive value, and likelihood ratio. The comparisons of the DALI to the other alcohol use disorder scales based on scores from the validation group are shown in table 2.

Cannabis or Cocaine Use Disorder Screen

The same procedures were then followed to develop a screen for cannabis and cocaine use disorders (abuse and dependence). In the index study group, 49 patients (19.8%) had current cannabis use disorder and 16 (6.5%) had current cocaine use disorder. Because of overlaps, 54 (21.9%) had cannabis or cocaine use disorder.

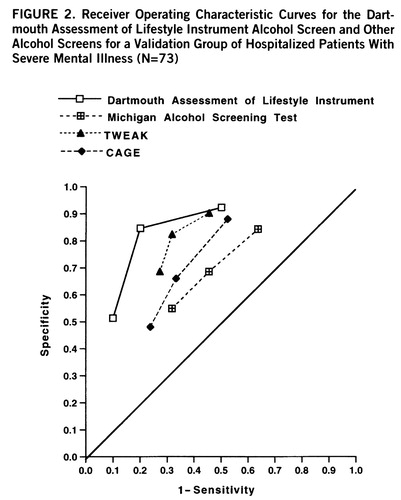

Using the same procedures to combine the best items from other scales, we developed the DALI drug questions. The DALI cannabis/cocaine screen consists of eight items, two of which are shared with the DALI alcohol screen. This scale yielded an overall classification accuracy for current cannabis or cocaine use disorder in the index study group of 89.5%. Figure 3 shows the receiver operating characteristic performance of the Drug Abuse Screening Test and Reasons for Drug Use Screening Test as compared to the DALI cannabis/cocaine questions in the index study group.

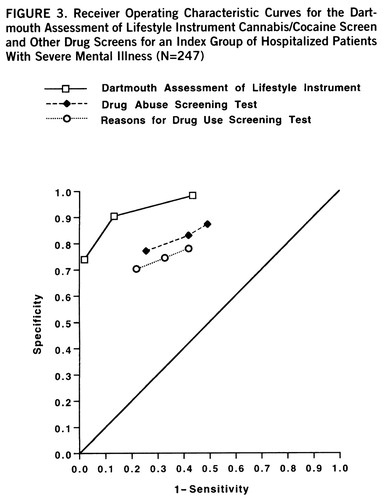

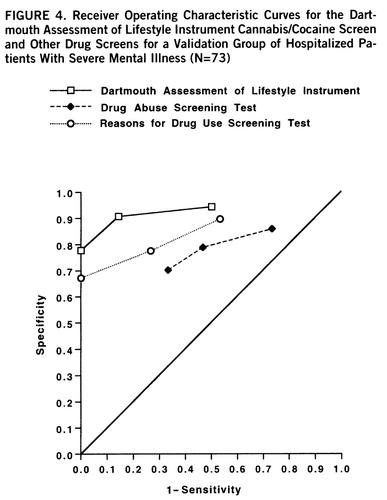

Among the validation group of 73 patients, 11 had cannabis use disorder, eight had cocaine use disorder, and owing to overlaps, 15 (20.5%) had drug use disorder overall. The classification accuracy of the DALI for cannabis or cocaine use disorder in the holdout group was 89.7% (61 of 68). Figure 4 displays the receiver operating characteristic curves for the DALI, the Reasons for Drug Use Screening Test, and the Drug Abuse Screening Test for the validation group.

We then followed the same procedures in order to compare the performance of the DALI drug scale to the performance of the other two drug abuse measures. The pairwise z value of the area under the curve for the DALI drug screen was significantly greater than the area under the curve for either the Drug Abuse Screening Test or the Reasons for Drug Use Screening Test (p<0.001), and the latter two areas were not significantly different from each other.

As with the alcohol screens, to compare the accuracy of the drug screens we calculated several commonly used statistics, including positive predictive value, negative predictive value, and likelihood ratio. The comparison of the DALI to the other drug use disorder scales based on the validation group is shown in table 3.

Description of DALI

The DALI is presented to patients as an 18-item, interviewer-administered scale. Three items, drawn from the Life-Style Risk Assessment Interview (40), are designed to reduce subject defensiveness and are not scored. Starting the screening interview in this manner was well received by the respondents. The remaining 15 items in the DALI are drawn from the Reasons for Drug Use Screening Test, TWEAK, CAGE, Drug Abuse Screening Test, Addiction Severity Index, and Life-Style Risk Assessment Interview. As in the original scales, many of the items do not explicitly refer to a specific time period (e.g., “How many drinks can you hold without passing out?”) but are useful in predicting current use disorder. Although the items have differential weighting in the discriminant function equation, the reported classification accuracy is achieved by using equal weightings for all questions. The average time for administering the scale to a patient is approximately 6 minutes. The DALI questionnaire, including scoring instructions and scale cutoff points, can be obtained directly from the authors, either by mail or directly from the New Hampshire-Dartmouth Psychiatric Research Center Web site (http://www.dartmouth.edu/dms/psychrc/). Interrater reliability, calculated for 40 interviews and five different interviewers, was as follows: alcohol questions, kappa=0.96; cannabis and cocaine questions, kappa=0.98; total scale, kappa=0.97. Test-retest reliability, calculated for 26 interviews, yielded a kappa coefficient of 0.90.

To evaluate how the DALI was affected by patient characteristics, we combined the two study groups (N=320) and examined gender, cognitive functioning (Mini-Mental State examination score ≥23), and diagnosis in relation to classification accuracy, using the Hanley and McNeil method (45). These analyses revealed no significant differences in classification accuracy according to any of these patient characteristics.

DISCUSSION

The DALI functioned well as a brief screen for detecting substance use disorder among psychiatric patients entering a state hospital in New Hampshire. It is short and easy to administer; it classified patients with a degree of accuracy that is comparable to the accuracy of screening tests used for other populations; and it outperformed existing brief screens in one validation group. Additional work is needed to evaluate its performance in other settings and with other groups of psychiatric patients. A self-administered version, using either paper and pencil or computer procedures, may be more efficient with less acutely ill respondents.

This study had several advantages over existing approaches. The criterion measure of substance use disorder provides the best approximation of a diagnostic “gold standard” for this population. The existence of a reliable, valid criterion measure permitted us to use current discriminative procedures for developing the screen. The study used a relatively large number of patients, and the 90.9% participation rate was higher than rates reported for other studies of similar populations. Finally, the study maximized generalizability by using a real-world setting where assessment is difficult and by assessing the majority of regularly admitted patients. We also used confidentiality procedures that matched those generally used in acute-care settings.

Unlike traditional methods of test construction, the logistic regression procedures used in this study were not intended to identify face-valid items or items from specific domains of assessment, such as pattern of use or consequences of use. Although many face-valid items were included in the candidate items, most of the optimal items were slightly indirect: “Have you ever attended an AA meeting?” or “Have you used marijuana in the past six months?” The final set of items in the DALI did address several dimensions of substance use disorder: patterns of use, loss of control, the physiological syndrome of dependence, consequences of use, and subjective distress. Many of the final items focus on use versus nonuse and on attempts to control use, rather than on quantity of use or frequency of use. These findings are consistent with observations that patients with severe mental illness are vulnerable to adverse consequences with relatively small amounts of use (47). The included items that reflect consequences emphasize relationships with family, and this focus is consistent with evidence showing that patients with severe mental illness have small social networks and often depend on families as their major supports (48).

The DALI was developed with a predominantly Caucasian, English-speaking, rural, New England population, in an inpatient setting, and in an environment where the rate of cocaine use is lower than rates in urban areas. Its generalizability to other populations and other settings obviously needs to be assessed. Establishing the validity of the DALI for different patient populations and in different settings is critical before the screening instrument enters general use. However, the results thus far provide encouragement that the DALI may be a more accurate screening instrument for substance use disorder in the psychiatric population than other currently available screens.

|

|

|

Presented at the 30th annual meeting of the Association for the Advancement of Behavior Therapy, New York, Nov. 21–24, 1996. Received Dec. 2, 1996; revision received May 13, 1997; accepted June 13, 1997. From the Department of Psychiatry, Dartmouth Medical School, and Department of Psychology, Dartmouth College, Hanover, N.H.; the New Hampshire-Dartmouth Psychiatric Research Center, Concord and Lebanon, N.H.; and the New Hampshire Hospital, C oncord, N.H. Address reprint requests to Dr. Rosenberg, New Ham pshire-Dartmouth Psychiatric Research Center, 2 Whipple Place, Lebanon, NH 03766; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by NIMH grants MH-50094 and MH-00839. The authors thank the clinical staff of the New Hampshire Hospital, for their cooperation and care of the patients described in this report, and the New Hampshire Division of Mental Health for support in gaining access to clients and providers in its facilities.

FIGURE 1. Receiver Operating Characteristic Curves for the Dartmouth Assessment of Lifestyle Instrument Alcohol Screen and Other Alcohol Screens for an Index Group of Hospitalized Patients With Severe Mental Illness (N=247)

FIGURE 2. Receiver Operating Characteristic Curves for the Dartmouth Assessment of Lifestyle Instrument Alcohol Screen and Other Alcohol Screens for a Validation Group of Hospitalized Patients With Severe Mental Illness (N=73)

FIGURE 3. Receiver Operating Characteristic Curves for the Dartmouth Assessment of Lifestyle Instrument Cannabis/Cocaine Screen and Other Drug Screens for an Index Group of Hospitalized Patients With Severe Mental Illness (N=247)

FIGURE 4. Receiver Operating Characteristic Curves for the Dartmouth Assessment of Lifestyle Instrument Cannabis/Cocaine Screen and Other Drug Screens for a Validation Group of Hospitalized Patients With Severe Mental Illness (N=73)

1. Coulehan JL, Zettler-Segal M, Block M, McClelland M, Schulberg HC: Recognition of alcoholism and substance abuse in primary care. Arch Intern Med 1987; 147:349–352Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Barry KL, Fleming MF, Greenley J, Widlak P, Kropp S, McKee P: Assessment of alcohol and other drug disorders in the seriously mentally ill. Schizophr Bull 1995; 21:313–321Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Drake RE, Osher FC, Noordsy DL, Hurlbut SC, Teague GB, Beaudette MS: Diagnosis of alcohol use disorders in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1990; 16:57–67Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Lehman AF, Myers CP, Dixon LB, Johnson JL: Detection of substance use disorders among psychiatric inpatients. J Nerv Ment Dis 1996; 184:228–233Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Mueser KT, Yarnold PR, Levinson DF, Singh H, Bellack AS, Kee K, Morrison RI, Yalalam KG: Prevalence of substance abuse in schizophrenia: demographic and clinical correlates. Schizophr Bull 1990; 16:31–56Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Regier DS, Farmer ME, Rae DS, Locke B, Keith S, Judd L, Goodwin F: Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse. JAMA 1990; 264:2511–2518Google Scholar

7. Cournos F, Empfield M, Horwath E, McKinnon K, Meyer I, Schrage H, Currie C, Agosin B: HIV seroprevalence among patients admitted to two psychiatric hospitals. Am J Psychiatry 1991; 148:1225–1230Google Scholar

8. Drake RE, Osher FC, Wallach MA: Alcohol use and abuse in schizophrenia: a prospective community study. J Nerv Ment Dis 1989; 177:408–414Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Haywood TW, Kravitz HM, Grossman LS, Cavanaugh JL Jr, Davis JM, Lewis DA: Predicting the “revolving door” phenomenon among patients with schizophrenic, schizoaffective, and affective disorders. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:856–861Link, Google Scholar

10. Linszen D, Dingemans P, Lenoir M: Cannabis abuse and the course of recent-onset schizophrenic disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:273–279Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Shaner A, Khalsa ME, Roberts L, Wilkins J, Anglin D, Hsieh S-C: Unrecognized cocaine use among schizophrenic patients. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:758–762Link, Google Scholar

12. Ananth J, Vandewater S, Kamal M, Brodsky A, Gamal R, Miller M: Missed diagnosis of substance abuse in psychiatric patients. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1989; 40:297–299Abstract, Google Scholar

13. Galletley CA, Field CD, Prior M: Urine drug screening of patients admitted to a state psychiatric hospital. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1993; 44:587–589Medline, Google Scholar

14. Stone A, Greenstein R, Gamble G, McLellan AT: Cocaine use in chronic schizophrenic outpatients receiving depot neuroleptic medications. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1993; 44:176–177Abstract, Google Scholar

15. Barbee JG, Clark PD, Craqanzano MS, Heintz GC, Kehoe CE: Alcohol and substance abuse among schizophrenic patients presenting to an emergency service. J Nerv Ment Dis 1989; 177:400–407Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Test MA, Wallisch LS, Allness DJ, Ripp K: Substance use in young adults with schizophrenic disorders. Schizophr Bull 1989; 15:465–476Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Goldfinger SM, Schutt RK, Seidman LJ, Turner WM, Penk WE, Tolomiczenko GS: Alternative measures of substance abuse among homeless mentally ill persons in the cross-section and over time. J Nerv Ment Dis 1996; 184:667–672Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Wolford GL, Rosenberg SD, Oxman TE, Drake RE, Mueser KT, Hoffman D, Vidaver RM: Evaluating existing methods for detecting substance use disorder in persons with severe mental illness, in Book of Abstracts, 1996 Midwinter Meeting of the Society for Personality Assessment. Falls Church, Va, Society for Personality Assessment, 1996Google Scholar

19. Selzer M: The Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test: the quest for a new diagnostic instrument. Am J Psychiatry 1971; 127:1653–1658Google Scholar

20. Hedlund JL, Vieweg BW: The Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (MAST): a comprehensive review. J Operational Psychiatry 1984; 15:55–65Crossref, Google Scholar

21. Searles JS, Alterman AI, Purtill JJ: The detection of alcoholism in hospitalized schizophrenics: a comparison of the MAST and MAC. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 1990; 14:557–560Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Mueser KT, Yarnold PR, Bellack AS: Diagnostic and demographic correlates of substance abuse in schizophrenia and major affective disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1992; 85:48–55Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Teague GB, Drake RE, McHugo GM, Vowinkle S: Alcohol and Substance Abuse, Housing, and Vocational Status in a Statewide Survey of Severely Mentally Ill Clients: Final Report to the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Rockville, Md, NIAAA, 1994Google Scholar

24. Toner BB, Gillies LA, Prendergast P, Cote FH, Browne C: Substance use disorders in a sample of Canadian patients with chronic mental illness. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1992; 43:251–254Abstract, Google Scholar

25. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MB: Instruction Manual for the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID). New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1988Google Scholar

26. Carey KB, Cocco KM, Simons JS: Concurrent validity of clinicians' ratings of substance abuse among psychiatric outpatients. Psychiatric Serv 1996; 47:842–847Link, Google Scholar

27. Drake RE, McHugo GM, Clark RE, Teague GB, Ackerson TH, Xie H, Miles KM: A clinical trial of assertive community treatment for patients with dual disorders. Am J Orthopsychiatry (in press)Google Scholar

28. Irvin EA, Flannery RB, Penk WE, Hanson MA: The Alcohol Use Scale: concurrent validity data. J Soc Behavior and Personality 1995; 10:899–905Google Scholar

29. Mueser KT, Nishith P, Tracy JI, DeGirolamo J, Molinaro M: Expectations and motives for substance use in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1995; 21:367–378Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Comtois KA, Ries R, Armstrong HE: Case manager ratings of the clinical status of dually diagnosed outpatients. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1994; 45:568–573Abstract, Google Scholar

31. Drake RE, Yovetich NA, Bebout RR, Harris M, McHugo GM: Integrated treatment for dually diagnosed homeless adults. J Nerv Ment Dis 1997; 185:298–305Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Mayfield D, McLeod G, Hall P: The CAGE questionnaire: validations of a new alcoholism screening instrument. Am J Psychiatry 1974; 131:1121–1123Google Scholar

33. Sokol RJ, Martier SS, Ager JW: The T-ACE questions: practical prenatal detection of risk drinking. Am J Obst Gyn 1989; 160:863–870Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Bottoms SF, Martier SS, Sokol RJ: Refinement in screening for risk drinking in reproductive aged women: the NET results (abstract). Alcoholism 1989; 13:339Google Scholar

35. Russell M, Martier SS, Sokol RJ, Mudar P, Bottoms S, Jacobson S, Jacobson J: Screening for pregnancy risk-drinking. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 1994; 18:1156–1161Google Scholar

36. Skinner HA: The Drug Abuse Screening Test. Addict Behav 1982; 7:363–371Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Grant B, Hasin DS, Harford TC: Screening for current drug use disorders in alcoholics: an application of receiver operating characteristic analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend 1988; 21:113–125Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Dworkin RJ: Researching Persons With Mental Illness: Applied Social Research Methods Series, vol 30. Newbury Park, Calif, Sage Publications, 1992Google Scholar

39. Derogatis LR: The SCL-90-R. Baltimore, Clinical Psychometric Research, 1993Google Scholar

40. Graham AW: Screening for alcoholism by life-style risk assessment in a community hospital. Arch Intern Med 1991; 151:958–964Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41. Lettieri D, Nelson JE, Sayers MA (eds): Treatment Handbook Series: Alcoholism Treatment Assessment Research Instruments. Washington, DC, National Institute on Alcohol and Alcohol Abuse, 1985Google Scholar

42. McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Woody GE, O'Brien CP: An improved diagnostic evaluation instrument for substance abuse patients: the Addiction Severity Index. J Nerv Ment Dis 1980; 168:26–33Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

43. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR: “Mini-Mental State”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975; 12:189–198Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

44. Kraemer H: Evaluating Medical Tests: Objective and Quantitative Guidelines. Newbury Park, Calif, Sage Publications, 1992Google Scholar

45. Hanley JA, McNeil BJ: The meaning and use of the area under a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Radiology 1982; 143:29–36Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

46. Hanley JA, McNeil BJ: A method for comparing the areas under receiver operating characteristic curves derived from same cases. Radiology 1983; 148:839–843Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

47. Lieberman J, Kinon B, Loebel A: Dopaminergic mechanisms in idiopathic and drug-induced psychoses. Schizophr Bull 1990; 16:97–110Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

48. Cresswell C, Kuipers L, Power M: Social networks and support in long-term psychiatric patients. Psychol Med 1992; 22:1019–1026Google Scholar