In This Issue

Childhood Trauma and Psychotic Symptoms

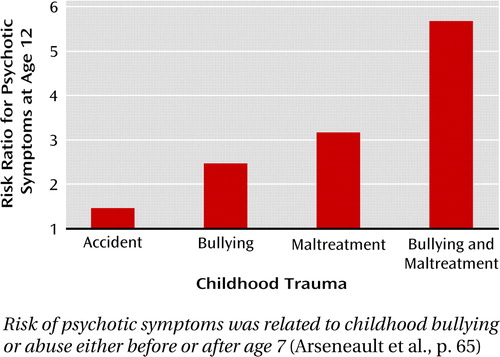

Abusive treatment of children, including bullying, increased the likelihood of psychotic symptoms at age 12 in a nationally representative sample of twins assessed between ages 5 and 12. Arseneault et al. (CME, p. Original article: 65) report that the effect of maltreatment was not related to genetic risk, socioeconomic status, and age at the time of maltreatment. Accidents were also associated with greater risk of psychotic symptoms at age 12 but to a lesser degree than traumas with the intention to harm. The combination of maltreatment by an adult and bullying by peers increased the risk of psychotic symptoms more than either one alone. The growing evidence of adverse long-term outcomes from childhood abuse is described by Cohen in an editorial (p. Original article: 7).

Risk of psychotic symptoms was related to childhood bullying or abuse either before or after age 7 (Arseneault et al., p. 65)

A Biological Predictor of PTSD?

The likelihood of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in Dutch military personnel sent to Afghanistan was greater in those with higher predeployment numbers of glucocorticoid receptors, conveyors of hormones affecting immunity, metabolism, and inflammation. The relationship discovered by van Zuiden et al. (p. Original article: 89) was independent of posttraumatic depressive symptoms and traumatic childhood experiences. With each increase of 1,000 glucocorticoid receptors in peripheral mononuclear cells, the odds of PTSD increased 7.5-fold. The increase persisted 1 and 6 months after deployment. Delahanty, in an editorial (p. Original article: 9), points out that there was considerable overlap in levels of glucocorticoid receptors between those who did and did not develop PTSD, but nonetheless this measure represents an interesting addition to the other risk factors that might help predict who develops PTSD.

A 20-year prospective study of the course of depressive disorder showed that nearly 25% of patients initially diagnosed as having unipolar major depressive disorder eventually developed either bipolar I or bipolar II mood disorder. Conversion to bipolar disorder was more frequent in patients with earlier onset and more severe symptoms, psychosis, and hypomanic symptoms. Less need for sleep, unusual energy, and increased goal-directed activities were the symptoms most frequently associated with later mania, according to Fiedorowicz et al. (p. Original article: 40). However, the majority of patients who later converted had no predictive signs. In his editorial (p. Original article: 4), Schneck suggests that in the absence of clinical or biomarker indicators for incipient bipolar disorder in most patients, it might be prudent to initiate psychoeducational approaches, such as family stress reduction and social rhythm therapies, with all young depressed patients and their families, to help mitigate the effects of a later conversion to bipolar disorder.

More Evidence Linking Suicide and Altitude

The relationship between suicide risk and elevation was confirmed by a nationwide study that also examined the possibility of intermediate roles of gun ownership and low population density. Kim et al. (p. Original article: 49) analyzed county- and state-level databases and found that rates of both firearm and non-firearm suicides were correlated with county altitude. Gun ownership and low population density were also associated with the suicide rate, but the role of altitude was separate from these other factors. To minimize the influence of cultural factors, the researchers conducted a parallel study in South Korea, which has variable geography and a relatively high suicide rate. Altitude and the number of suicides over a 4-year period again showed a strong correlation. This association does not indicate a causal relationship between elevation and suicide, but mild hypoxia may increase metabolic stress in people with mood disorders.