Anxiety and Outcome in Bipolar Disorder

Abstract

Objective: Important differences exist between bipolar disorder with and without comorbid anxiety, but little is known about the long-term prognostic significance of coexisting anxiety in bipolar disorder. The authors sought to identify the anxiety features most predictive of subsequent affective morbidity and to evaluate the persistence of the prognostic relationship. Method: Probands with bipolar I or II disorder from the National Institute of Mental Health Collaborative Depression Study were followed prospectively for a mean of 17.4 years (SD=8.4) and were characterized according to various manifestations of anxiety present at baseline. A series of general linear model analyses examined the relationship between these measures and the proportion of follow-up weeks in episodes of major depression and in episodes of mania or hypomania. Results: Patients whose episode at intake included a depressive phase spent nearly three times as many weeks in depressive episodes than did those whose intake episode was purely manic. Psychic and somatic anxiety ratings, but not the presence of panic attacks or of any lifetime anxiety disorder, added to the predictive model. Combined ratings of psychic and somatic anxiety were associated in a stepwise fashion with a greater proportion of weeks in depressive episodes, and this relationship persisted over the follow-up period. Conclusions: The presence of higher levels of anxiety during bipolar mood episodes appears to mark an illness of substantially greater long-term depressive morbidity.

It is has long been appreciated that the presence of prominent anxiety in major depressive episodes is associated with a greater severity and persistence of depressive symptoms, whether the anxiety manifests as panic attacks (1 – 4) or as more global dimensions of anxiety (5 – 8) . Recent work has focused on the significance of anxiety in bipolar disorder and has yielded similar results. Bipolar patients with high anxiety levels or with coexisting DSM-IV anxiety disorders appear to have a higher likelihood of rapid switching (9 – 11) and of suicidal behavior (12) , shorter euthymic periods (12) , poorer treatment response (13 , 14) , and, in the only large-scale follow-up study on the topic, a longer time to remission from the index affective episode (15) .

In this study, we used data from a long-term, high-surveillance-intensity follow-up of patients with bipolar I or II disorder to determine the effects of comorbid anxiety on subsequent affective morbidity. The analyses address the following questions in particular: What is the effect of anxiety on the time spent in depressive or manic (or hypomanic) episodes? What measure of anxiety best reflects this relationship? How persistent is the relationship? Does this effect vary by age, sex, or index episode polarity (depressed, manic, or polyphasic)?

Method

Participants

The National Institute of Mental Health Collaborative Depression Study recruited inpatients and outpatients who satisfied Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC) (16) for major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, or schizoaffective disorder from 1978 to 1981. All were seeking treatment at one of five academic centers: Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston; New York State Psychiatric Institute and Columbia-Presbyterian Hospital in New York City; Rush Presbyterian Hospital in Chicago; Washington University in St. Louis; and the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics in Iowa City. Inclusion criteria required that participants be at least 18 years old, not mentally retarded, English-speaking, Caucasian, and knowledgeable of their biological parents.

In the present study, patients with manic or hypomanic syndromes manifesting before intake or at any time during follow-up were designated as having bipolar disorder. The course of those whose first episode of mania or hypomania appeared during follow-up was nevertheless tracked from study entry. Those with RDC schizoaffective disorder, other than the mainly schizophrenic subtype, were also included. The RDC-defined mainly schizophrenic subtype of schizoaffective disorder is equivalent to DSM-IV schizoaffective disorder, but the remainder of RDC schizoaffective manic or depressed patients nearly all meet DSM-IV criteria for bipolar or major depressive disorder with mood-incongruent psychotic features.

Procedures

After participants provided informed consent, professional raters conducted structured interviews using the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (SADS) (17) . Item ratings and the resulting diagnoses integrated information from the interview, from review of medical records, and from informants when available.

Follow-up assessments then took place semiannually for the subsequent 5 years and annually thereafter. Raters used the Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Evaluation (LIFE) (18) and later variants (the LIFE-II and the Streamlined Longitudinal Interval Continuation Evaluation) to record descriptions of the clinical course and psychosocial outcome based on direct interview and on medical record review.

These instruments used the LIFE psychiatric symptom ratings to track all RDC syndromes that had been active at intake or that developed during follow-up. Interviewers helped patients identify points at which symptom levels had changed and then quantified symptom levels between those points. For major depression, bipolar disorder, schizoaffective depression, and schizoaffective mania, symptom levels were assigned scores ranging from 1 to 6, with 1 indicating no symptoms, 2 indicating the presence of one or two symptoms to a mild degree, 3 and 4 indicating the continued presence of an episode with less than the number of symptoms necessary for an initial diagnosis, 5 indicating a full syndrome, and 6 indicating a relatively severe full syndrome. An episode was defined as ended after 8 consecutive weeks of psychiatric symptom ratings no greater than 2; a new episode was declared when the patient again met criteria for definite major depression, mania, or schizoaffective disorder. For hypomania, minor depression, and intermittent depressive disorders, symptoms were rated on a 3-point scale in which 3 indicated a full syndrome; recovery was defined as 8 consecutive weeks with ratings of 1.

Data Analyses

We selected the persistence of depressive episodes as the principal outcome measure because earlier analyses have shown that depression dominates the symptomatic course of the bipolar disorders (19 , 20) . This measure, which we here call “depressive morbidity,” was quantified as the percentage of follow-up weeks in episodes of major, schizoaffective, minor, or intermittent depressive disorders as indicated by psychiatric symptom ratings of 3 or more for any of the syndromes.

Because the presence or absence of cycling in an index episode, as well as the index episode’s phase, have established prognostic importance (21 – 24) , patients were initially grouped according to the polarity of their intake episode at the time of the baseline assessment as purely manic, purely depressed, cycling, or mixed. Only 11 patients were in mixed episodes, and because mixed states appear (in prognostic terms) simply to be extreme forms of rapid cycling, we included these patients with those who were cycling, as we have done in earlier studies (25) . The three groups were compared by baseline demographic and clinical measures and by the principal outcome measure, the proportion of weeks of follow-up in depressive episodes, to determine whether these groups should be separated or combined in the analyses of outcome prediction.

We likewise tested for significant relationships between percentage time in depressive episodes and sex, age at intake, lifetime non-anxiety comorbid diagnoses (alcoholism, drug dependence, and antisocial personality disorder), bipolar type (I versus II), intake episode polarity (cycling, pure depressive, or pure manic), and four measures of concurrent anxiety—presence or absence of panic attacks within the index episode, presence of any lifetime RDC anxiety disorder (panic disorder, phobic disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, or generalized anxiety disorder), and the 6-point SADS ratings of somatic and psychic anxiety (items 263 and 265). The somatic anxiety item specifies “physiological concomitants of anxiety other than during panic attacks” and lists as examples headaches, stomach cramps, diarrhea, and muscle tension. The psychic anxiety item specifies “subjective feelings” of anxiety, fearfulness, or apprehension, excluding panic attacks. The 6-point scales for each range from 1 for no anxiety at all to 6 for “extreme,” indicating “pervasive feelings of intense anxiety.”

These anxiety measures were entered into an SPSS (version 16.0) general linear model to determine which added to the prediction of time depressed. Sex, age at intake, non-anxiety comorbid diagnoses, bipolar type, or episode polarity was included in the model if univariate analysis had shown that factor to have a significant relationship to time depressed.

After selecting the most salient predictor of subsequent morbidity, we tested for the persistence of the relationship by considering depressive morbidity in each of four 5-year periods that comprised the follow-up period. These analyses were restricted to patients who completed the respective 5-year follow-up periods.

These procedures were repeated for the prediction of proportion of weeks in episodes of mania, schizoaffective mania, or hypomania. Two-tailed tests and an alpha of 0.05 were used throughout.

Results

Of 333 patients who entered the Collaborative Depression Study with a current or past mania or hypomania and another 102 patients who first developed a manic episode during the follow-up period, 71 (16.2%) were known to have died within 20 years (19 [4.3%] by suicide) and another 126 (28.8%) failed to complete follow-up for other reasons. Eight (2.4%) were followed for less than a year and were excluded from the analyses, leaving 427.

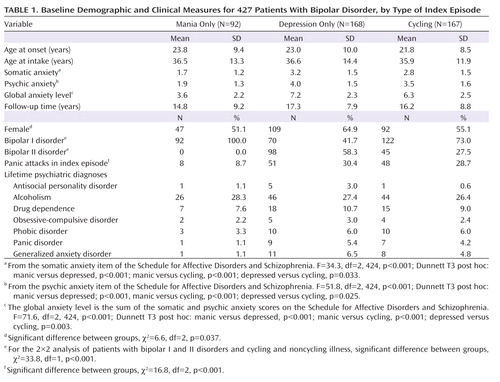

Table 1 summarizes participants’ demographic and clinical measures at baseline, by type of index episode.

Depressive Episodes

The percentage of weeks in depressive episodes during follow-up was not predicted by sex, age at intake, age at illness onset, or presence of antisocial personality disorder, alcoholism, or drug dependence. The 284 patients with past or future manic episodes (bipolar I) were in depressive episodes for a lesser percentage of weeks during follow-up (mean=27.4% [SD=28.1]), than were the 143 with only episodes of hypomania (bipolar II) (mean=36.5% [SD=27.7]) (t=–3.2, df=427, p=0.001). A strong relationship existed between baseline episode polarity and subsequent time in depressive episodes; mean values were 13.2% (SD=20.1) of follow-up weeks for those who entered the study with a pure manic episode, 37.7% (SD=27.1) for those who entered with a pure depressive episode, and 33.0% (SD=29.6) for those who had been in a cycling episode (F=25.8, df=2, 424, p<0.001; Dunnett T3 test: manic versus depressed, p<0.001; manic versus cycling, p<0.001). Those in pure depressive episodes did not differ significantly from those who cycled, however (Dunnett T3 test: p=0.871), and because baseline anxiety measures also separated the pure mania group from the other two, subsequent analyses condensed patient grouping to two polarity categories: pure mania and pure depression or cycling. When bipolar type and polarity category were entered together, polarity category was predictive (F=37.6, p<0.001) and bipolar type was not. Subsequent analyses therefore included only polarity category.

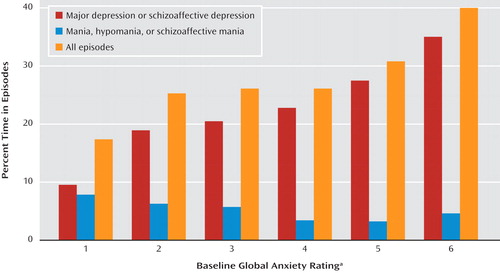

When tested individually, together with polarity category, neither the presence nor the absence of panic attacks in the index episode, nor the presence or absence of any anxiety disorder, predicted subsequent time in depressive episodes, but somatic (F=7.9, p=0.005) and psychic (F=11.2, p=0.001) anxiety did. With these two measures together, psychic anxiety remained highly significant (F=7.0, p=0.008), and somatic anxiety was of borderline significance (F=3.8, p=0.052). Because somatic anxiety appeared to add somewhat to the prediction of time depressed, the two measures were combined into a single measure of anxiety level (global anxiety level) for further analyses. When this scale was, for graphic purposes, condensed from 12 to 6 points and plotted against the proportion of follow-up weeks in depressive episodes, a continuous relationship emerged with no prognostically meaningful threshold for the separation of anxious and nonanxious patients ( Figure 1 ).

a The global anxiety rating was computed as the sum of the somatic and psychic anxiety scores on the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia, divided by 2.

Combinations of global anxiety level and index episode polarity yielded large outcome differences. The 80 patients with a purely manic index episode and with a baseline global anxiety level below the median value of 7 spent a mean of only 12.4% (SD=20.2) of the follow-up weeks in depressive episodes. The 12 patients with mania who had anxiety ratings of 7 or above were in depressive episodes for 18.8% (SD=18.3) of follow-up weeks, and the corresponding figures for those with depressed or cycling index episodes were 29.7% (SD=28.4) and 40.4% (SD =27.6), respectively, for groups below (N=156) and above (N=176) the anxiety median.

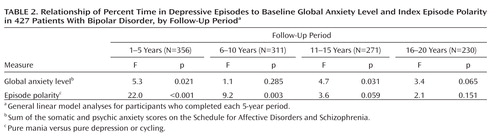

A series of general linear model analyses for each of the four 5-year follow-up periods showed that the relationship between index episode polarity at intake and proportion of follow-up time in depressive episodes for patients who completed those periods faded after the first 10 years, while global anxiety continued to predict, although at more modest or trend levels, throughout the 20 years ( Table 2 ).

Manic or Hypomanic Episodes

Neither sex nor baseline age was associated with subsequent time in manic or hypomanic episodes, nor were the presence or absence of alcoholism, drug abuse, antisocial personality disorder, or any anxiety disorder. Both index episode polarity and bipolar type predicted subsequent manic or hypomanic morbidity, and when both were included in a general linear model, bipolar type (I versus II) was predictive (F=31.0, p<0.001), but episode polarity was not. When the presence of any anxiety disorder, panic attacks, somatic anxiety, and psychic anxiety were entered individually in general linear model analyses with bipolar type, none were predictive. Global anxiety level, though, was significantly related to manic or hypomanic morbidity (F=4.4, p=0.036) such that higher levels of anxiety were associated with less subsequent time in manic or hypomanic episodes (partial correlation=–0.101, p=0.036).

Discussion

Bipolar patients with high global anxiety levels, as quantified in combined 6-point ratings of psychic and somatic anxiety, went on to experience a greater proportion of weeks in major depressive episodes and a lesser proportion of weeks in manic or hypomanic episodes during a follow-up period of up to 20 years. The continuous, stepwise dose effect of initial global anxiety level on subsequent affective morbidity favors a dimensional over a categorical view of anxiety in bipolar disorder, at least for this important outcome measure.

The phase of index episode at the time of intake was also strongly associated with subsequent depressive morbidity such that patients who had entered the study in a purely manic episode experienced substantially less depressive morbidity. This is consistent with a report early in the Collaborative Depression Study follow-up (25) that showed that recovery 1 year after intake was much more likely for those bipolar patients whose index episode was purely manic than for those whose index episode was depressed or cycling. The present findings show that the prognostic importance of episode polarity extends well beyond a year. Although episode polarity and a combined measure of psychic and somatic anxiety were highly interrelated at intake, both were independently predictive of subsequent depressive morbidity. These two factors together thus comprise a powerful prognostic formulation.

As with long-term follow-up studies generally, the Collaborative Depression Study did not assign or control treatment. Although essentially all participants were receiving some type of medication for affective disorder when they began the study, many were subsequently without somatic treatment for extended periods (23 – 28) . Earlier analyses showed that Collaborative Depression Study participants whose previous episodes were more frequent or severe received more intensive somatotherapy and that after control for these antecedent variables, the intensity of somatotherapy was associated with a higher likelihood of recovery from a given episode (27 , 28) . If higher levels of psychic and somatic anxiety and a subsequently greater persistence of depressive symptoms resulted in higher intensities of somatotherapy, the results of that treatment would have tended to lessen the apparent relationship between these anxiety levels and later depressive morbidity. The results described here are therefore more likely to underestimate than to overestimate the relationship between anxiety level and subsequent depressive morbidity.

The observation that the strength of the relationship between psychic and somatic anxiety and depressive morbidity changed little over a 20-year period indicates that such anxiety levels mark a type of bipolar illness rather than a phase of an individual’s bipolar illness. This type may well reflect the permanent effects of childhood trauma on a course of illness; others have shown that such trauma in patients with bipolar disorder is correlated with both higher levels of anxiety and lower likelihoods of recovery (29) . The Collaborative Depression Study did not obtain measures of childhood trauma, however, and we therefore cannot assess this relationship.

The combination of presenting phase and anxiety level appears to offer a potent clinical tool for predicting whether an individual is likely to follow a course dominated by depressive symptoms or one in which mania is more prominent. Such prediction is inherently valuable but may also have practical importance in the selection of a mood-stabilizer regimen designed to offer more protection against one or the other pole of bipolar illness.

These findings also fit well with evidence from family studies that the coexistence of panic attacks and bipolar disorder in probands substantially increases the risk for the same comorbidity in family members (9 , 30) . Such comorbidity thus may help to identify phenotypes with unique genetic determinants. It remains a challenge, however, to identify an optimal threshold for separating bipolar episodes with low and high levels of anxiety for such investigations.

1. Coryell W, Endicott J, Andreasen NC, Keller MB, Clayton PJ, Hirschfeld RM, Scheftner WA, Winokur G: Depression and panic attacks: the significance of overlap as reflected in follow-up and family study data. Am J Psychiatry 1988; 145:293–300Google Scholar

2. Grunhaus L, Pande AC, Brown MB, Greden JF: Clinical characteristics of patients with concurrent major depressive disorder and panic disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:541–546Google Scholar

3. Johnson J, Weissman MM, Klerman GL: Panic disorder, comorbidity, and suicide attempts. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1990; 47:805–808Google Scholar

4. VanValkenburg C, Akiskal HS, Puzantian V, Rosenthal T: Anxious depressions: clinical, family history, and naturalistic outcome: comparisons with panic and major depressive disorders. J Affect Disord 1984; 6:67–82Google Scholar

5. Clayton PJ, Grove WM, Coryell W, Keller M, Hirschfeld R, Fawcett J: Follow-up and family study of anxious depression. Am J Psychiatry 1991; 148:1512–1517Google Scholar

6. Fawcett J, Scheftner WA, Fogg L, Clark DC, Young MA, Hedeker D, Gibbons R: Time-related predictors of suicide in major affective disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1990; 147:1189–1194Google Scholar

7. Mykletun A, Bjerkeset O, Dewey M, Prince M, Overland S, Stewart R: Anxiety, depression, and cause-specific mortality: the HUNT study. Psychosom Med 2007; 69:323–331Google Scholar

8. Fava M, Rush AJ, Alpert JE, Balasubramani GK, Wisniewski SR, Carmin CN, Biggs MM, Zisook S, Leuchter A, Howland R, Warden D, Trivedi MH: Difference in treatment outcome in outpatients with anxious versus nonanxious depression: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry 2008; 165:342–351Google Scholar

9. MacKinnon DF, Zandi PP, Cooper J, Potash JB, Simpson SG, Gershon E, Nurnberger J, Reich T, DePaulo JR: Comorbid bipolar disorder and panic disorder in families with a high prevalence of bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159:30–35Google Scholar

10. MacKinnon DF, Zandi PP, Gershon E, Nurnberger JI Jr, Reich T, DePaulo JR: Rapid switching of mood in families with multiple cases of bipolar disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003; 60:921–928Google Scholar

11. Nwulia EA, Zandi PP, McInnis MG, DePaulo JR Jr, MacKinnon DF: Rapid switching of mood in families with familial bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord 2008; 10:597–606Google Scholar

12. Simon NM, Otto MW, Wisniewski SR, Fossey M, Sagduyu K, Frank E, Sachs GS, Nierenberg AA, Thase ME, Pollack MH (STEP-BD Investigators): Anxiety disorder comorbidity in bipolar disorder patients: data from the first 500 participants in the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD). Am J Psychiatry 2004; 161:2222–2229Google Scholar

13. Feske U, Frank E, Mallinger AG, Houck PR, Fagiolini A, Shear MK, Grochocinski VJ, Kupfer DJ: Anxiety as a correlate of response to the acute treatment of bipolar I disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:956–962Google Scholar

14. Frank E, Cyranowski JM, Rucci P, Shear MK, Fagiolini A, Thase ME, Cassano GB, Grochocinski VJ, Kostelnik B, Kupfer DJ: Clinical significance of lifetime panic spectrum symptoms in the treatment of patients with bipolar I disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2002; 59:905–911Google Scholar

15. Otto MW, Simon NM, Wisniewski SR, Miklowitz DJ, Kogan JN, Reilly-Harrington NA, Frank E, Nierenberg AA, Marangell LB, Sagduyu K, Weiss RD, Miyahara S, Thas ME, Sachs GS, Pollack MH: Prospective 12-month course of bipolar disorder in out-patients with and without comorbid anxiety disorders. Br J Psychiatry 2006; 189:20–25Google Scholar

16. Spitzer RL, Endicott J, Robins E: Research Diagnostic Criteria: rationale and reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1978; 35:773–782Google Scholar

17. Endicott J, Spitzer RL: A diagnostic interview: the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1978; 35:837–844Google Scholar

18. Keller MB, Lavori PW, Friedman B, Nielsen E, Endicott J, McDonald-Scott P, Andreasen NC: The Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation: a comprehensive method for assessing outcome in prospective longitudinal studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1987; 44:540–548Google Scholar

19. Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, Endicott J, Maser J, Solomon DA, Leon AC, Rice JA, Keller MB: The long-term natural history of the weekly symptomatic status of bipolar I disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2002; 59:530–537Google Scholar

20. Judd LL, Schettler PJ, Akiskal HS, Maser J, Coryell W, Solomon D, Endicott J, Keller M: Long-term symptomatic status of bipolar I vs bipolar II disorders. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2003; 6:127–137Google Scholar

21. Angst J, Gamma A, Pezawas L, Ajdacic-Gross V, Eich D, Rossler W, Altamura C: Parsing the clinical phenotype of depression: the need to integrate brief depressive episodes. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2007; 115:221–228Google Scholar

22. Angst J, Gerber-Werder R, Zuberbuhler HU, Gamma A: Is bipolar I disorder heterogeneous? Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2004; 254:82–91Google Scholar

23. Keller MB: The course of manic-depressive illness. J Clin Psychiatry 1988; 49(suppl):4–7Google Scholar

24. Keller MB, Lavori PW, Coryell W, Andreasen NC, Endicott J, Clayton PJ, Klerman GL, Hirschfeld RM: Differential outcome of pure manic, mixed/cycling, and pure depressive episodes in patients with bipolar illness. JAMA 1986; 255:3138–3142Google Scholar

25. Keller MB, Lavori PW, Klerman GL, Andreasen NC, Endicott J, Coryell W, Fawcett J, Rice JP, Hirschfeld RM: Low levels and lack of predictors of somatotherapy and psychotherapy received by depressed patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1986; 43:458–466Google Scholar

26. Dawson R, Lavori PW, Coryell WH, Endicott J, Keller MB: Course of treatment received by depressed patients. J Psychiatr Res 1999; 33:233–242Google Scholar

27. Leon AC, Solomon DA, Mueller TI, Endicott J, Rice JP, Maser JD, Coryell W, Keller MB: A 20-year longitudinal observational study of somatic antidepressant treatment effectiveness. Am J Psychiatry 2003; 160:727–733Google Scholar

28. Dawson R, Lavori PW, Coryell WH, Endicott J, Keller MB: Maintenance strategies for unipolar depression: an observational study of levels of treatment and recurrence. J Affect Disord 1998; 49:31–44Google Scholar

29. Neria Y, Bromet EJ, Carlson GA, Naz B: Assaultive trauma and illness course in psychotic bipolar disorder: findings from the Suffolk County Mental Health Project. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2005; 111:380–383Google Scholar

30. Doughty CJ, Wells JE, Joyce PR, Olds RJ, Walsh AE: Bipolar-panic disorder comorbidity within bipolar disorder families: a study of siblings. Bipolar Disord 2004; 6:245–252Google Scholar