Dr. Schneck Replies

To the Editor: We appreciate the comments by Dr. Bhattacharyya et al. They raise a number of important questions regarding the methodology and statistical analysis used in our study, notably the possibility that we underestimated the prevalence of rapid cycling at the end of the study by including only those patients who completed 1 year of treatment.

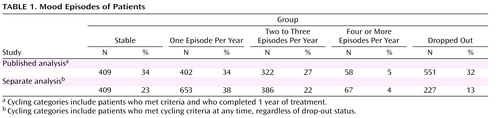

To address this issue, we conducted a separate analysis that included all patients who were either stable for 1 year or who had at least one episode prior to dropping out of the study and compared these results with our original results ( Table 1 ). Patients who were stable when they discontinued the study were not included. Using this method, the relative percentages of patients assigned to the “frequent cycling” category (i.e., two to three episodes per year) decreased from 27% to 22%, and the percentage of patients in the rapid-cycling category (four or more episodes per year) decreased from 5% to 4%. Therefore, it appears that those patients who experienced more mood episodes were not more likely to drop out relative to those patients who experienced fewer episodes.

We agree with Dr. Bhattacharyya et al. that recall bias may have led to the large percentage of reported rapid-cycling patients at the study entry, which we highlighted in our discussion. However, patients’ recall of prior episodes is commonly used in studies of rapid cycling in order to estimate prevalence rates (1 , 2) and is consistent with everyday clinical practice. Moreover, it is usually not feasible to independently verify the number of prior episodes. In our study, patient reports of rapid cycling were adequate to predict future cycling and to predict increased cycle frequency while undergoing antidepressant treatment. Thus, the mood instability described by patients retrospectively as rapid cycling appears to be consequential. Additionally, our use of strict DSM-IV criteria to demarcate prospectively observed mood episodes, as well as the model practice procedures employed by the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD) psychiatrists, also likely contributed to the decline in cycling rates.

What contribution, if any, did comorbidities play in the development of rapid cycling? The large number of patients enrolled in our study limited the number of variables that could be reliably captured. However, studies examining the role of medical comorbidities (particularly hypothyroidism and gonadal steroid effects) and their relationship to rapid cycling have yielded either negative or equivocal results (3 , 4) . Studies of substance abuse and its association with rapid cycling have also yielded mixed results. For example, in our earlier study (5) , rates of substance abuse among rapid cycling bipolar I and II disorder patients were equivalent (36%), although Kupka et al. (6) found an association between rapid cycling and substance abuse in patients with bipolar I disorder.

The comments by Dr. Battacharyya et al. highlight the complexities in studying the course of bipolar disorder in general and in rapid cycling in particular. We hope that future studies using the STEP-BD data set may provide a better understanding of rapid cycling patients over the course of their 4 years in the STEP-BD study.

1. Maj M, Magliano L, Pirozzi R, Marasco C, Guarneri M: Validity of rapid cycling as a course specifier for bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:1015–1019Google Scholar

2. Bauer MS, Calabrese J, Dunner DL, Post R, Whybrow PC, Gyulai L, Tay LK, Younkin SR, Bynum D, Lavori P: Multisite data reanalysis of the validity of rapid cycling as a course modifier for bipolar disorder in DSM-IV. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:506–515Google Scholar

3. Valle J, Ayuso-Gutierrez JL, Abril A, Ayuso-Mateos JL: Evaluation of thyroid function in lithium-naive bipolar patients. Eur Psychiatry 1999; 14:341–345Google Scholar

4. Leibenluft E, Ashman SB, Feldman-Naim S, Yonkers KA: Lack of relationship between menstrual cycle phase and mood in a sample of women with rapid cycling bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry 1999; 46:577–580Google Scholar

5. Schneck CD, Miklowitz DJ, Calabrese JR, Allen MH, Thomas MR, Wisniewski SR, Miyahara S, Shelton MD, Ketter TA, Goldberg JF, Bowden CL, Sachs GS: Phenomenology of rapid-cycling bipolar disorder: data from the first 500 participants in the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program. Am J Psychiatry 2004; 161:1902–1908Google Scholar

6. Kupka RW, Luckenbaugh DA, Post RM, Suppes T, Altshuler LL, Keck PE Jr, Frye MA, Denicoff KD, Grunze H, Leverich GS, McElroy SL, Walden J, Nolen WA: Comparison of rapid-cycling and non-rapid-cycling bipolar disorder based on prospective mood ratings in 539 outpatients. Am J Psychiatry 2005; 162:1273–1280Google Scholar