Prevalence and Predictors of Lipid and Glucose Monitoring in Commercially Insured Patients Treated With Second-Generation Antipsychotic Agents

Abstract

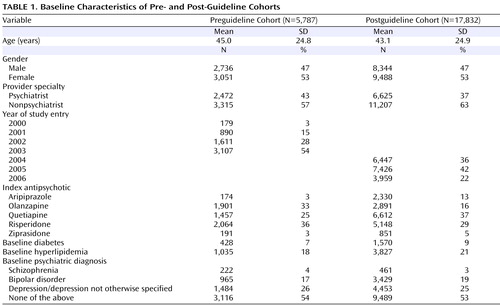

Objective: The authors sought to quantify plasma lipid and glucose testing rates in patients receiving second-generation antipsychotics before and after guidelines recommending testing were issued in February 2004 by the American Diabetes Association (ADA). Method: In this retrospective cohort analysis using data from a large managed care database (PharMetrics, 2000–2006), patients under age 65 on second-generation antipsychotics were identified and followed from 40 days before to 130 days after the antipsychotic prescription was written. Baseline and 12-week (40 days) lipid and glucose testing rates were determined for pre- and postguideline cohorts. Logistic regression analyses determined predictors of baseline and 12-week lipid and glucose testing while controlling for covariates. Results: A total of 5,787 preguideline patients and 17,832 postguideline patients were identified. Baseline lipid testing rates were 8.4% for the preguideline cohort and 10.5% for the postguideline cohort, and the 12-week testing rates were 6.8% and 9.0%, respectively. Baseline glucose testing rates were 17.3% for the preguideline cohort and 21.8% for the postguideline cohort, and the 12-week testing rates were 14.1% and 17.9%, respectively. All four comparisons were statistically significant. Baseline and 12-week testing rates for lipids and glucose in children were the lowest of all age groups. Conclusions: Despite statistically significant improvements after the ADA guidelines were issued, monitoring for plasma lipids and glucose in this population remains low. Clinicians and administrators responsible for the health of at-risk populations should implement new approaches for effective monitoring of major modifiable risk factors for medical morbidity and mortality in patients taking second-generation antipsychotics.

Individuals with psychiatric disorders have a higher rate of premature mortality related to medical conditions, including cardiovascular disease and diabetes mellitus, with coronary heart disease as the leading cause of death (1 , 2) . The increased risk of mortality related to coronary heart disease can be explained in part by undermonitoring and undertreatment of risk factors in patients with psychiatric disorders compared with the general population (3 – 5) . In individuals with severe mental illness, primary and secondary cardiovascular disease prevention efforts are less likely to be undertaken (4) , and there is an overall reduced frequency of standard health care checks and treatment for physical health problems (6) . Standard risk-reduction approaches include screening for key modifiable risk factors, including smoking, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and hyperglycemia. The American Diabetes Association (ADA) Cardiometabolic Risk Initiative underscores the increase in risk for both cardiovascular disease and diabetes that can occur in relation to increases in the prevalence of these risk factors (7) .

The third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III), sponsored by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, describes screening procedures in the general population as well as in high-risk groups (8) . These include specific screening of plasma lipids and glucose, with the frequency of screening largely determined by the level of risk or in relation to interventions.

While various disease, lifestyle, and health care delivery issues can affect cardiometabolic risk in this population, there is substantial evidence that antipsychotic treatment can influence risk through effects on body weight as well as on lipid and glucose metabolism (3 , 9 – 15) . In addressing this topic in early 2004, a consensus development conference convened by four key organizations—ADA, APA, the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, and the North American Association for the Study of Obesity—recommended that all patients receiving second-generation antipsychotics, regardless of diagnosis, “should receive appropriate baseline screening and ongoing monitoring” (9) . The conference report specifically recommended that fasting lipids and glucose be assessed at baseline and after 12 weeks of treatment. Around the same time, antipsychotic manufacturers and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) agreed on additional warnings regarding the risk of hyperglycemia during treatment with second-generation antipsychotics, including a recommendation for regular or periodic monitoring for symptoms and, in at-risk patients, testing (16) . Thus, it is now considered essential that all patients who receive second-generation antipsychotics be monitored for metabolic side effects and managed appropriately to minimize their cardiometabolic risk. Metabolic monitoring is even more important in light of the growing use of antipsychotics, both for recently approved indications for aripiprazole and risperidone in the treatment of adolescent schizophrenia and bipolar disorder and in frequent off-label uses (17) . Furthermore, the average age of antipsychotic users is declining as a result of the increasing use of second-generation antipsychotics in younger populations (17) .

Evidence regarding the use of the screening of lipids and glucose in patients treated with second-generation antipsychotics as recommended in Adult Treatment Panel III, either annually or in conjunction with the prescription of these agents, as recommended by the ADA and FDA, has not been encouraging. Recently, Morrato et al. (5) conducted a retrospective multistate Medicaid cohort study evaluating testing rates from 1998 to 2003. They observed that lipid and glucose testing was underutilized in patients receiving second-generation antipsychotics prior to the ADA guidelines. On average, less than 20% of individuals starting therapy with a second-generation antipsychotic received baseline glucose testing, and less than 10% received lipid testing. Initial prescription of an antipsychotic was associated with only a 2%–3% increase in lipid testing and a 7%–11% increase in glucose testing. Patients below age 20 were less likely to receive testing. While these results indicate low rates of lipid and glucose testing in accordance with the recommendations from Adult Treatment Panel III, FDA, and ADA, the question remains as to whether the low rates of monitoring are limited to the Medicaid sector or are similarly low in managed care populations. There may be reason to believe that the Medicaid sector is less effectively monitored for various medical conditions in comparison with managed care populations (18) . Using a large national managed care database, we conducted a retrospective study of managed care patients receiving second-generation antipsychotics to quantify lipid and glucose testing in relation to antipsychotic treatment, before and after the ADA guidelines were issued.

Method

Study Design

This was a longitudinal retrospective cohort study using data for 2000–2006 from the PharMetrics Database, a large national insurance claims database providing integrated insurance claims data from more than 70 different managed care organizations. The database includes information on inpatient, outpatient, and pharmacy claims.

Study Population

The study population included patients with a prescription claim for a second-generation antipsychotic (aripiprazole, olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, or ziprasidone) who had been continuously enrolled in a commercial health plan for at least 6 months before and 4 months after the index prescription date. Patients enrolled in other health plan types (Medicaid, Medicare, self-insured, and other) were excluded in order to reduce demographic variability. For inclusion in the study, patients had to be under 65 years of age, not to have received previous drug therapy with a second-generation antipsychotic for a least 6 months prior to the index date, and to have received continuous treatment (less than a 45-day gap between prescriptions) with a second-generation antipsychotic (not necessarily the index agent) for at least 4 months after the index date. Two cohorts were defined for comparison: the preguideline cohort, which comprised patients with an index prescription date between July 1, 2000, and September 30, 2003, and the postguideline cohort, comprising patients with index prescription date between March 1, 2004, and November 30, 2006. Although the ADA consensus statement was published in February 2004, we defined the end of the preguideline period as September 30, 2003, to allow for a 12-week follow-up period free of influence from the guidelines. We defined the postguideline period as beginning in the first full month after publication of the guidelines.

Identification of Lipid and Glucose Testing

All lipid and glucose testing procedures were identified using the codes from Current Procedural Terminology, 4th Revision (CPT). Glucose testing was identified by codes for a comprehensive metabolic panel (80050, 80053, and 80054), glucose test (82947, 82948, 82950, 82951, 81000, 81002, 81005, and 81099), glycated hemoglobin (A1C) testing (83036), or home glucose-monitoring device (82962). Lipid testing was defined as the presence of a lipid panel (CPT code 80061) or individual tests (CPT codes 83721, 83715, 83716, or [83718 and 82465 and 84478]).

The ADA recommends lipid and glucose testing at initiation of treatment with a second-generation antipsychotic and again 12 weeks later (9) . The rates of lipid and glucose monitoring at the beginning of treatment (baseline) were calculated as the proportion of patients starting medication who had at least one medical claim for a lipid or glucose test, respectively, during the period 40 days before or after the index prescription claim date. This provides a “window” into testing on or around initiation of the second-generation antipsychotic to allow for the imprecision of timing in claims data. The rates of lipid and glucose monitoring at 12-week follow-up were calculated as the proportion of patients who had at least one medical claim for a lipid or glucose test, respectively, within 84±40 days of the index prescription claim date.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, N.C.). Descriptive statistics were calculated for demographic variables of the pre- and postguideline cohorts. Testing rates were compared across cohorts using unadjusted analyses. Chi-square tests were used to compare categorical variables, and t tests to compare continuous variables. Analyses included comparison of baseline characteristics between cohorts as well as rates of lipid and glucose monitoring at baseline and week 12.

Univariate analysis was conducted on rates of lipid and glucose monitoring during treatment in the pre- and postguideline cohorts. Lipid and glucose monitoring rates were also stratified by age for both cohorts. For the characterization and comparison of patients in the preguideline versus postguideline cohorts, unadjusted analyses were conducted using chi-square tests for categorical variables and t tests for continuous variables. Analyses included comparison of baseline characteristics, rate of lipid monitoring at baseline and at 12 weeks, and rate of glucose monitoring at baseline and at 12 weeks.

Multivariate logistic regression was performed to determine predictors of glucose and lipid monitoring at baseline and at week 12 after controlling for the following covariates: age; sex; psychiatric diagnosis (bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, depression/depression not otherwise specified, or none); number of prior primary care visits (≤1 or >1 office visits to a designated primary care provider [internal medicine, family medicine, general practitioner, pediatrician, etc.] in the 180 days before the index date); baseline (within 180 days before the index date) metabolic comorbidity (diabetes, obesity, or dyslipidemia identified using ICD-9 diagnosis codes or a prescription for diabetes, lipid, or weight-control medication identified using National Drug Codes); index antipsychotic agent; calendar year; provider specialty; and monitoring at baseline (for week 12 models). For age, the 55–64 age category was chosen as the referent because descriptive analyses indicated that patients in this group had the highest rates of monitoring. For index antipsychotic agent, olanzapine was chosen as the referent because it is the drug with the most evidence for metabolic effects to date, suggesting that it may be associated with the highest monitoring rates.

Results

A total of 27,623 patients in the database were identified as having a prescription for a second-generation antipsychotic. Of these, 4,004 patients were excluded (1,148 in the preguideline cohort and 2,856 in the postguideline cohort) because they were not enrolled in commercial health plans, which left 23,619 patients for analysis (5,787 in the preguideline cohort and 17,832 in the postguideline cohort). Baseline demographic characteristics ( Table 1 ) were similar between cohorts, with the exception of the index second-generation antipsychotic, which showed variation between cohorts, most likely reflecting changes due to the more recent introduction of aripiprazole and ziprasidone.

Metabolic Testing Rates (Univariate Analysis)

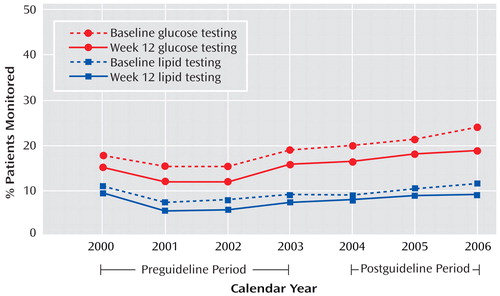

Overall, only a low percentage of patients had any lipid or glucose testing at baseline or at 12 weeks during treatment with the index second-generation antipsychotic ( Figure 1 ). The rates of lipid and glucose testing showed low, statistically significant increases in the postguideline cohort compared with the preguideline cohort at both baseline and week 12 (all p values <0.001). Overall rates of metabolic monitoring by calendar year are shown in Figure 2 . Glucose monitoring rates were higher than lipid monitoring rates, baseline monitoring rates were higher than week 12 rates, and there was a small increase in the proportion of patients who were monitored for metabolic effects in the post- versus preguideline periods.

a All four group comparisons significant at p<0.001.

a The American Diabetes Association guidelines were issued in February 2004.

Stratification of lipid and glucose testing rates by age showed that older patients were more frequently tested for metabolic effects ( Figure 3 ), in both the pre- and postguideline periods. Stratification of lipid and glucose testing rates by specific antipsychotic agent showed some differences in monitoring rates among the different agents ( Figure 4 ). The introduction of the guidelines does not appear to have had a great effect on the variability of monitoring among second-generation antipsychotics in this crude analysis.

Predictors of Metabolic Testing (Multivariate Analysis)

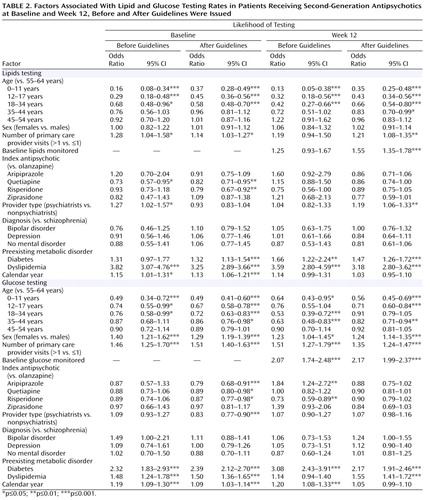

Table 2 summarizes the factors associated with lipid and glucose monitoring at baseline and week 12, in both the pre- and postguideline cohorts. This analysis confirmed that age was a significant factor in metabolic monitoring, in both the pre- and postguideline periods for both lipid and glucose monitoring. Up to age 34, increasing age consistently increased the likelihood of lipid or glucose testing at baseline and week 12, before and after the guidelines were issued. Gender had no impact on lipid testing, but males were significantly less likely than females to receive glucose testing, in the pre- and postguideline periods, at baseline and week 12.

Other factors influencing monitoring rates included number of primary care provider visits, preexisting metabolic disorders, and calendar year. Number of primary care provider visits prior to the index prescription generally had a significant impact on the likelihood of metabolic monitoring; patients with more than one visit to their primary care provider were consistently more likely to receive lipid and glucose monitoring than those with one or no visits, in both pre- and postguideline periods, with the exception of preguideline week 12 lipid testing. The presence of preexisting metabolic disorders generally increased the likelihood of lipid or glucose monitoring. Preexisting diabetes was associated with a significantly greater likelihood of lipid and glucose monitoring at all times, with the exception of preguideline baseline lipid testing. Pre- and postguideline values were similar. Preexisting dyslipidemia was associated with a significantly greater likelihood of lipid and glucose monitoring at all times, with the exception of glucose testing at week 12 in the preguideline period. Increasing calendar year was a significant predictor of glucose monitoring at both baseline and week 12 in the preguideline period and at baseline in the postguideline period. Calendar year was associated with lipid monitoring only at baseline in both the pre- and postguideline periods.

The specific antipsychotic agent prescribed showed no consistent effect on the likelihood of monitoring. Postguideline baseline lipid testing was significantly more likely in patients receiving olanzapine than in those receiving quetiapine or risperidone, and postguideline baseline glucose testing was significantly more likely in patients receiving olanzapine than in those receiving aripiprazole, quetiapine, risperidone, or ziprasidone. In the preguideline period, week 12 glucose testing was significantly more likely in patients receiving olanzapine than in those receiving risperidone but significantly less likely in those receiving olanzapine than in those receiving aripiprazole. The type of health care provider was generally not a predictor of metabolic monitoring in the pre- or postguideline period. Diagnosis was not predictive of monitoring rates.

Discussion

The results of this analysis of more than 23,000 managed care patients receiving antipsychotic treatment indicate that monitoring of plasma lipids and glucose at treatment initiation or at the recommended interval of 12 weeks after initiation has been relatively uncommon, both before and after the ADA and FDA issued recommendations for monitoring this patient population. These results are in line with a survey (19) showing that less than 30% of psychiatrists measured lipid or glucose levels in most patients prior to initiating treatment with a second-generation antipsychotic. Our results also extend a previous report (5) of low monitoring rates in a multistate Medicaid sample prior to 2004, in which a similar pattern of low screening and monitoring was observed in an insured managed care population both before and several years after the ADA and FDA recommendations were issued. While rates of lipid and glucose monitoring did tend to increase over the period covered in this analysis, and there was a statistically significant increase in rates from the pre- to the postguideline period, no major increase in monitoring rates was seen in proximity to the period during which the FDA and ADA recommendations were issued, and the rates of lipid and glucose monitoring overall remained low; by 2006, just over 10% of patients received lipid monitoring and just over 20% of patients received glucose monitoring. Given the leading role of premature coronary heart disease in the overall mortality of patients commonly treated with antipsychotic medications, the low rates of monitoring indicate a missed opportunity for appropriate prevention-related screening and intervention (4) .

The results also indicate that patients who had more than one primary care provider visit had higher rates of monitoring, which suggests the importance of designating a clinician to focus on general medical health. It cannot be determined from this study whether this effect was related to patients with recognized diabetes or dyslipidemia receiving multiple primary care provider visits for required lipid and glucose monitoring, or whether the same beneficial effect could accrue from more than one visit with a psychiatric clinician similarly focused on general health concerns in addition to psychiatric treatment. The observation that older patients tended to have higher levels of lipid and glucose monitoring may similarly reflect the greater likelihood that older patients will encounter clinicians who are appropriately focused on screening for common general health conditions. Older patients may have had higher levels of monitoring as a result of a prior ADA recommendation that low-risk individuals undergo diabetes screening every 3 years beginning at age 45, with earlier and more screening recommended for those with elevated risk (20) . Higher levels of monitoring related to age have also been observed in the general population (21) . Despite evidence that children and adolescents are at increasing risk of type 2 diabetes (22 , 23) and are increasingly being treated with antipsychotics (23 – 27) , the results of this study indicate that younger patients were the least likely to be screened and monitored, both before and after the ADA and FDA recommendations were issued. This is of particular concern because children and adolescents have been reported to be more susceptible to the weight gain and metabolic adverse effects associated with antipsychotic treatment (28) .

In general, monitoring rates at or around week 12 were lower than rates at initiation of treatment. This may reflect clinicians screening for baseline risk but not following up with monitoring after treatment has been initiated. This pattern is concerning, because data from published reports and the FDA Medwatch drug surveillance system suggest that a high proportion of new-onset diabetes cases occur within 6 months of initiation of antipsychotic therapy (29 – 32) . Moreover, an analysis of data from the Veterans Health Administration has shown that the elevated risk of diabetes in patients with schizophrenia taking second-generation antipsychotics is higher in younger age groups (33) . There was no consistent effect of individual antipsychotic medication choice on the overall pattern of monitoring rates. While this result is consistent with the ADA and FDA guidelines, which did not recommend preferential monitoring based on the specific antipsychotic prescribed, this observation may have more to do with a floor effect than with adherence to ADA or FDA recommendations.

The main advantage of using the large PharMetrics claims database to analyze physician behavior over the course of several years is the large patient population available for analysis, which increases the generalizability of the findings. However, the results of this study are subject to a number of limitations. For one thing, as this was a retrospective database analysis, data were limited to those recorded in the database. Thus, information on a number of important clinical parameters that may influence further monitoring—such as weight, diet, family history, and prior treatment history and laboratory values—was unavailable and could not be controlled for in the analyses. In addition, the sample was not evenly distributed through the study period, and we cannot be certain that the same patients were represented in the database at each time point. Furthermore, in this study we evaluated metabolic monitoring per se and did not investigate how the results of monitoring may have affected a clinician’s psychiatric treatment plan, such as switching a patient with metabolic abnormalities to an antipsychotic less likely to cause metabolic disturbances. Similarly, this analysis was restricted to the proactive monitoring of metabolic health at the time of antipsychotic initiation and 12 weeks later in order to assess the rates of adherence to the guidelines, which specifically focus on the importance of monitoring at these time points. An assessment of whether the duration of antipsychotic exposure affects monitoring rates over time was beyond the scope of this study. A final limitation is that this analysis was limited to commercial health care plans in order to reduce demographic variability, which limits the generalizability of these findings to public-sector patients. However, this study complements the Medicaid population study by Morrato et al. (5) , and together the two studies provide broad generalizability to a variety of clinical settings.

The observation of very low rates of monitoring of lipid and glucose levels both at initiation of antipsychotic treatment and during the course of treatment suggests that adoption of either the ADA or FDA recommendations has not been widespread. This is remarkable since these guidelines were widely promoted, in a consistent way, by a variety of organizations, including the ADA, the FDA, several pharmaceutical companies, and a substantial number of journal articles and continuing medical education activities. Given that 1) this is a patient population that has a higher prevalence of cardiometabolic risk factors, such as overweight and obesity, hyperglycemia, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and smoking, 2) this population has a reduced life expectancy primarily because of premature cardiovascular disease, and 3) screening and prevention are known to be effective in reducing cardiovascular mortality, the evidence that monitoring rates remain low indicates that new approaches are needed to enhance screening and safety monitoring for cardiometabolic risk in this population (4) .

1. Colton CW, Manderscheid RW: Congruencies in increased mortality rates, years of potential life lost, and causes of death among public mental health clients in eight states. Prev Chronic Dis 2006; 3:A42Google Scholar

2. Parks J, Svendsen D, Singer P, Foti ME (eds): Morbidity and Mortality in People With Serious Mental Illness. Alexandria, Va, National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors, Medical Directors Council, Oct 2006. http://www.nasmhpd.org/general_files/publications/med_directors_pubs/Mortality and Morbidity Final Report 8.18.08.pdfGoogle Scholar

3. Nasrallah HA, Meyer JM, Goff DC, McEvoy JP, Davis SM, Stroup TS, Lieberman JA: Low rates of treatment for hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes in schizophrenia: data from the CATIE schizophrenia trial sample at baseline. Schizophr Res 2006; 86:15–22Google Scholar

4. Newcomer JW, Hennekens CH: Severe mental illness and risk of cardiovascular disease. JAMA 2007; 298:1794–1796Google Scholar

5. Morrato EH, Newcomer JW, Allen RR, Valuck RJ: Prevalence of baseline serum glucose and lipid testing in users of second-generation antipsychotic drugs: a retrospective, population-based study of Medicaid claims data. J Clin Psychiatry 2008; 69:316–322Google Scholar

6. Roberts L, Roalfe A, Wilson S, Lester H: Physical health care of patients with schizophrenia in primary care: a comparative study. Fam Pract 2007; 24:34–40Google Scholar

7. Eckel RH, Kahn R, Robertson RM, Rizza RA: Preventing cardiovascular disease and diabetes: a call to action from the American Diabetes Association and the American Heart Association. Diabetes Care 2006; 29:1697–1699Google Scholar

8. National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III): Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation 2002; 106:3143–3421Google Scholar

9. American Diabetes Association; American Psychiatric Association; American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists; North American Association for the Study of Obesity: Consensus development conference on antipsychotic drugs and obesity and diabetes. Diabetes Care 2004; 27:596–601Google Scholar

10. Meyer JM, Koro CE: The effects of antipsychotic therapy on serum lipids: a comprehensive review. Schizophr Res 2004; 70:1–17Google Scholar

11. Newcomer JW: Second-generation (atypical) antipsychotics and metabolic effects: a comprehensive literature review. CNS Drugs 2005; 19:1–93Google Scholar

12. Allison DB, Mentore JL, Heo M, Chandler LP, Cappelleri JC, Infante MC, Weiden PJ: Antipsychotic-induced weight gain: a comprehensive research synthesis. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:1686–1696Google Scholar

13. Koro CE, Fedder DO, L’Italien GJ, Weiss S, Magder LS, Kreyenbuhl J, Revicki D, Buchanan RW: An assessment of the independent effects of olanzapine and risperidone exposure on the risk of hyperlipidemia in schizophrenic patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2002; 59:1021–1026Google Scholar

14. Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, McEvoy JP, Swartz MS, Rosenheck RA, Perkins DO, Keefe RS, Davis SM, Davis CE, Lebowitz BD, Severe J, Hsiao JK: Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia. N Engl J Med 2005; 353:1209–1223Google Scholar

15. Stroup TS, Lieberman JA, McEvoy JP, Swartz MS, Davis SM, Rosenheck RA, Perkins DO, Keefe RSE, Davis CE, Severe J, Hsiao JK, CATIE Investigators: Effectiveness of olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, and ziprasidone in patients with chronic schizophrenia following discontinuation of a previous atypical antipsychotic. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163:611–622Google Scholar

16. US Food and Drug Administration: 2004 safety alert: Zyprexa (olanzapine), March 1, 2004. http://www.fda.gov/medwatch/SAFETY/2004/zyprexa.htmGoogle Scholar

17. Domino ME, Swartz MS: Who are the new users of antipsychotic medications? Psychiatr Serv 2008; 59:507–514Google Scholar

18. Halpern MT, Ward EM, Pavluck AL, Schrag NM, Bian J, Chen AY: Association of insurance status and ethnicity with cancer stage at diagnosis for 12 cancer sites: a retrospective analysis. Lancet Oncol 2008; 9:222–231Google Scholar

19. Buckley PF, Miller DD, Singer B, Arena J, Stirewalt EM: Clinicians’ recognition of the metabolic adverse effects of antipsychotic medications. Schizophr Res 2005; 79:281–288Google Scholar

20. ADA: Screening for type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2003; 26(suppl 1):S21–S24Google Scholar

21. Rifas-Shiman SL, Forman JP, Lane K, Caspard H, Gillman MW: Diabetes and lipid screening among patients in primary care: a cohort study. BMC Health Serv Res 2008; 8:25Google Scholar

22. Narayan KM, Boyle JP, Thompson TJ, Sorensen SW, Williamson DF: Lifetime risk for diabetes mellitus in the United States. JAMA 2003; 290:1884–1890Google Scholar

23. Growth in Medication Use in Children, 2001–2006. Franklin Lakes, NJ, Medco Health Solutions, 2007Google Scholar

24. Fegert JM: [Specific features and problems in the pharmacotherapy of schizophrenic psychoses in children and adolescents]. Z Arztl Fortbild Qualitatssich 2002; 96:597–603 (German)Google Scholar

25. Hugtenburg JG, Heerdink ER, Tso YH: Psychoactive drug prescribing by Dutch child and adolescent psychiatrists. Acta Paediatr 2005; 94:1484–1487Google Scholar

26. Zito JM, Safer DJ, dosReis S, Gardner JF, Boles M, Lynch F: Trends in the prescribing of psychotropic medications to preschoolers. JAMA 2000; 283:1025–1030Google Scholar

27. Zito JM, Safer DJ, Valluri S, Gardner JF, Korelitz JJ, Mattison DR: Psychotherapeutic medication prevalence in Medicaid-insured preschoolers. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2007; 17:195–203Google Scholar

28. Safer DJ: A comparison of risperidone-induced weight gain across the age span. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2004; 24:429–436Google Scholar

29. Koller E, Schneider B, Bennett K, Dubitsky G: Clozapine-associated diabetes. Am J Med 2001; 111:716–723Google Scholar

30. Koller EA, Cross JT, Doraiswamy PM, Schneider BS: Risperidone-associated diabetes mellitus: a pharmacovigilance study. Pharmacotherapy 2003; 23:735–744Google Scholar

31. Koller EA, Doraiswamy PM: Olanzapine-associated diabetes mellitus. Pharmacotherapy 2002; 22:841–852Google Scholar

32. Koller EA, Weber J, Doraiswamy PM, Schneider BS: A survey of reports of quetiapine-associated hyperglycemia and diabetes mellitus. J Clin Psychiatry 2004;65:857–863Google Scholar

33. Lambert BL, Cunningham FE, Miller DR, Dalack GW, Hur K: Diabetes risk associated with use of olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone in Veterans Health Administration patients with schizophrenia. Am J Epidemiol 2006; 164:672–681Google Scholar