A Naturalistic Study of Consecutive Agitated Emergency Department Patients Treated With Intramuscular Olanzapine Prior to Consent

To the Editor: There is currently a larger body of evidence concerning injectable atypical antipsychotics relative to conventional antipsychotics, and expert consensus favors the use of injectable atypical antipsychotics in agitated patients (1) . However, the American College of Emergency Physicians considers the evidence from extant studies of injectable atypical antipsychotics to be class II as a result of the populations used in modern trials. In the view of the American College of Emergency Physicians Clinical Policy Committee, findings from selected, consented, less agitated clinical trial subjects may not generalize to typical unselected, involuntary emergency patients (2). Injectable antipsychotics are used prior to medical assessment. Hence, data for efficacy and safety in unselected patients are critical, and observational studies in more relevant populations are required (3) . To acquire a typical, unselected population of agitated patients, we obtained permission from the ethical committee of the Hospital “La Citadelle,” Liège, Belgium, to treat patients who refused oral medication according to an established protocol. Under this arrangement, patients received the medication they would have received either voluntarily or involuntarily as usual care for agitated behavior. Consent for the diagnostic interview and use of the research data were obtained after resolution of the episode. Two subjects refused consent, and their data were destroyed. The data were made anonymous prior to the analyses reported in the present study.

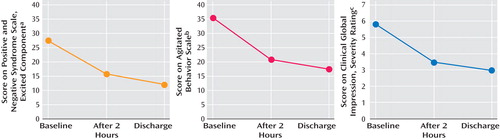

Measures were collected prospectively for patients with acute agitation who presented consecutively to an urban emergency department. Measures included the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale-Excited Component (PANSS-EC), Agitated Behavior Scale, and Clinical Global Impression Severity. Under local clinical policy, agitated patients who refused oral medication received olanzapine (10 mg, intramuscular). Patients with known substance use disorders, pregnancy, unstable diabetes, or intolerance to olanzapine were excluded. Assessments occurred 1) at baseline, 2) 2 hours postinjection, and 3) at discharge 12 to 24 hours postbaseline. Vital signs and adverse effects were assessed at these same time points. Diagnosis was ascertained using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV. The population reported in the present study included 21 women and 19 men (mean age=37.3 [SD=12.2] years) who were diagnosed for psychotic disorders (schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorders [60%]), bipolar disorders (mania [25%]), and personality disorders (15%). Physical restraint was required for 30 patients (75%), and four patients (10%) required subsequent injections. No other psychotropic medications were permitted.

Consistent with the expectation of higher agitation scores in unselected patients, the mean baseline PANSS-EC score was 27.5 (SD=4.23) versus a mean range of 12.39 to 19.7 in blinded, randomized, placebo controlled studies of olanzapine for the treatment of agitation (4 – 6) . There were statistically significant reductions from baseline in PANSS-EC, Agitated Behavior Scale, and Clinical Global Impression Severity scores 2 hours after the first intramuscular injection ( Figure 1 ). Consistent with reductions in agitation, there was a reduction in blood pressure (systolic/diastolic) of 8.2 (SD=3.1)/3.3 (SD=1.2) mmHg and in pulse of 8.7 (SD=1) beats per minute. There were no complaints of dizziness reported spontaneously or on enquiry. Although asymptomatic, seven patients experienced a 20 mmHg drop in systolic pressure and 10 experienced a 10 mmHg drop in diastolic pressure 2 hours postinjection. One patient’s pulse decreased 20 beats per minute from 110 to 90. No patient had a pulse below 70 at any time point. In addition, no instances of excessive sedation were observed. Increases in Simpson Angus Scale and Barnes Akathisia Scale scores were not statistically significant.

a t=10.59, p<0.0001

b t=12.00, p<0.0001

c t=11.43, p<0.0001

To our knowledge, this is the first observational study of olanzapine with consecutive enrollment and treatment prior to consent. Data are consistent with the findings of controlled trials in selected populations. However, the magnitude of effects should be interpreted cautiously, since the benefits of antipsychotics appear twice as large in studies without placebo comparison relative to those with placebo comparison. No conclusions can be reached about the relative efficacy of olanzapine and standard treatments such as haloperidol. The data also confirm the need for vigilance with respect to vital signs. Our sample is not large enough to inform the frequency of more serious but less common adverse effects.

1. Allen MH, Currier GW, Carpenter D, Ross RW, Docherty JP; Expert Consensus Panel for Behavioral Emergencies 2005: The expert consensus guideline series: treatment of behavioral emergencies 2005. J Psychiatr Pract 2005; 11:5–108Google Scholar

2. Lukens TW, Wolf SJ, Edlow JA, Shahabuddin S, Allen MH, Currier GW, Jagoda AS: Clinical policy: critical issues in the diagnosis and management of the adult psychiatric patient in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med 2006; 47:79–99Google Scholar

3. Damsa C, Adam E, De Gregorio F, Cailhol L, Lejeune J, Lazignac C, Allen MH: Intramuscular olanzapine in patients with borderline personality disorder: an observational study in an emergency room. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2007; 29:51–53Google Scholar

4. Breier A, Meehan K, Birkett M, David S, Ferchland I, Sutton V, Taylor CC, Palmer R, Dossenbach M, Kiesler G, Brook S, Wright P: A double-blind, placebo-controlled dose-response comparison of intramuscular olanzapine and haloperidol in the treatment of acute agitation in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2002; 59:441–448Google Scholar

5. Meehan K, Zhang F, David S, Tohen M, Janicak P, Small J, Koch M, Rizk R, Walker D, Tran P, Breier A: A double-blind, randomized comparison of the efficacy and safety of intramuscular injections of olanzapine, lorazepam, or placebo in treating acutely agitated patients diagnosed with bipolar mania. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2001; 21:389–397Google Scholar

6. Wright P, Birkett M, David SR, Meehan K, Ferchland I, Alaka KJ, Saunders JC, Krueger J, Bradley P, San L, Bernardo M, Reinstein M, Breier A: Double-blind, placebo-controlled comparison of intramuscular olanzapine and intramuscular haloperidol in the treatment of acute agitation in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:1149–1151Google Scholar