Efficacy of Sibutramine for the Treatment of Binge Eating Disorder: A Randomized Multicenter Placebo-Controlled Double-Blind Study

Abstract

Objective: Preliminary evidence suggests that the antiobesity agent sibutramine is effective in the treatment of binge eating disorder, impacting both binge eating and weight. This study is the first large-scale, multisite, placebo-controlled trial to test the efficacy of sibutramine in binge eating disorder. Method: Participants (N=304) who met DSM-IV criteria for binge eating disorder were randomly assigned to 24 weeks of double-blind sibutramine (15 mg) or placebo treatment. The outcome measures included the frequency of eating binges (primary outcome), binge day frequency, body mass index, body weight, global improvement, response categories, associated eating pathology, and quality of life. The primary analysis for continuous measures was the difference between groups in the change from baseline to endpoint using analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the last observation carried forward. Results: Compared with subjects receiving placebo, participants who received sibutramine had a significantly greater reduction in weekly binge frequency (sibutramine group mean=2.7 [SD=1.7], placebo group mean=2.0 [SD=2.3]); weight loss (sibutramine group mean=4.3 kg [SD=4.8], placebo group mean=0.8 kg [SD=3.5]); reduction in frequency of binge days; reduction in body mass index; global improvement; level of response, including the percentage of abstinence from binge eating (sibutramine group: 58.7%; placebo group: 42.8%); and reduction in eating pathology (cognitive restraint, disinhibition, and hunger). The change in quality of life scores was not significant. Sibutramine was associated with significantly higher incidence of headache, dry mouth, constipation, insomnia, and dizziness. Conclusions: This trial demonstrated the efficacy of sibutramine in reducing binge eating, weight, and associated psychopathology.

Binge eating disorder is characterized by recurrent episodes of binge eating accompanied by feelings of loss of control and marked distress in the absence of regular compensatory behaviors. The prevalence of binge eating disorder in the general population is 2%–3% (1) . Binge eating disorder usually occurs in conjunction with obesity—a condition associated with many adverse health consequences, including hypertension, type 2 diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and cardiovascular disease (2) . Yet obese individuals with binge eating disorder are a distinctive subset of the obese population, and relative to obese individuals without binge eating disorder, they show higher rates of psychiatric comorbidity, more medical complaints and psychosocial impairment, and poorer quality of life (3) . Accordingly, treatment for binge eating disorder ideally targets the multiple problems of binge eating, body weight, and psychopathology.

Several psychological treatments, particularly cognitive behavior therapy and interpersonal psychotherapy, demonstrate robust improvements in binge eating and associated specific and general psychopathology in both the short- and long-term (4) . However, while these treatments can result in clinically significant weight loss for participants who cease binge eating (5 , 6) , the majority fail to achieve weight loss of this magnitude. Moreover, results from behavioral weight loss studies of obese patients with binge eating disorder have yielded very modest or equivocal findings for weight loss efficacy (6 , 7) . Thus, to date, psychological treatments alone have not been effective in treating the overweight and obesity issues associated with binge eating disorder.

Medications that have been examined in randomized placebo-controlled trials for the treatment of binge eating disorder include the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) fluvoxamine (8 , 9) , sertraline (10) , fluoxetine (6 , 11 , 12) , and citalopram (13) ; the antiobesity agents d -fenfluramine (14) (withdrawn from the market in 1997), sibutramine (15 , 16) , and orlistat (17) ; the anticonvulsants topiramate (18 , 19) and zonisamide (20) ; and the norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor atomoxetine (21) . Although many of these medications induced statistically superior reductions in binge eating and weight compared with placebo (8 – 11 , 13 – 21) , only sibutramine, orlistat, topiramate, and zonisamide produced large, clinically significant drug-placebo differences in weight change (15 , 16 – 20) . In general, these studies have evaluated small samples and have been of relatively brief duration (e.g., 6–16 weeks).

Sibutramine, a serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, appears to modify internal signals that control hunger and satiation (22) . Sibutramine has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the inducement and maintenance of weight loss (23 , 24) , and its efficacy for the treatment of obese patients has been well established (25) . Sibutramine has been shown to suppress food intake during episodes of binge eating (26) , and preliminary findings suggest that sibutramine also effectively and safely addresses the multiple problems of obese patients with binge eating disorder (15 , 16) . Thus, further examination of this agent for binge eating disorder is warranted. The present study is a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, parallel-group, multicenter study designed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of 24 weeks of sibutramine treatment in binge eating disorder.

Method

Participants

Participants were men and women between the ages of 18 and 65, with a body mass index <45 kg/m 2 (there was no minimum body mass index requirement), who met DSM-IV criteria for binge eating disorder. Recruitment was conducted through advertisements at 18 participating sites. Participants were excluded if they had blood pressure >140/90 mm Hg; pulse >95 bpm; history of stroke, narrow angle glaucoma, cardiac disease, seizures, or renal or hepatic dysfunction; use of insulin, medications known to affect weight, or certain psychoactive medications (monoamine oxidase inhibitors, lithium, SSRIs, opioids); current participation in a weight loss program; surgical treatment for obesity; bulimia nervosa or purging in the past 6 months; alcohol or drug abuse in the past year; current psychiatric condition being treated with a psychoactive agent; current major depressive disorder; history of anorexia nervosa, psychosis, bipolar disorder, or suicide attempts; or psychotherapy within the previous 2 months. Women were excluded if they were pregnant, lactating, or not practicing adequate contraceptive precautions if fertile. All participating sites received review and approval from their respective institutional review boards to conduct the study.

Study Design

Interested participants completed a screening assessment during which the study was described, and written informed consent was obtained prior to the performance of any study procedures. Following screening, eligible participants entered the run-in phase, consisting of 4 weeks of single-blind placebo treatment. Two visits occurred at 2-week intervals during the 4-week run-in period. At each visit, participants received a 5- to 10-minute session of dietary/life style psychoeducation, which included information on caloric intake and portion control. A pamphlet, “On Your Way to Fitness” (27) , was distributed at the first visit. At each visit, participants submitted binge episode diaries.

Following the run-in phase, individuals eligible for participation were those who continued to meet binge eating disorder diagnostic criteria and had not experienced a marked decrease in binge eating; specifically, they had a minimum of 4 days with binge eating episodes over the previous 2 weeks, and the average number of binge episodes/week for those 2 weeks was >25% of the number for the week preceding the beginning of the run-in phase. These participants were randomly assigned to 24 weeks of double-blind treatment with either sibutramine, 15 mg/day, or placebo. Medication was provided in coded identical bottles containing the visually identical capsules of sibutramine or placebo. The 15-mg dose is the highest FDA-approved dose for sibutramine (23) and was selected to study in this new indication. Participants were randomly assigned by a computer-generated table, and a separate schedule was prepared for each center. Seven visits were conducted over the double-blind treatment period, biweekly during the first 4 weeks and monthly thereafter.

Diagnostic Assessment and Outcome Measures

The binge eating disorder diagnosis was determined at the time of screening using the binge eating disorder diagnostic version of the Eating Disorder Examination, an investigator-based, semistructured interview designed to provide an assessment of binge eating disorder (derived from the Eating Disorder Examination 12.0D [28] ), which has established reliability and validity (29) . The Eating Disorder Examination was conducted by assessors trained in its administration by its developer (Christopher Fairburn, M.D.).

Participants recorded their binge eating episodes, defined as “episodes of overeating during which you feel out of control,” in a daily diary. Participants recorded the time, content, ratings of loss of control, and distress related to such episodes. These episodes were reviewed and verified at each study visit by an investigator using the Eating Disorder Examination.

At each study visit, weight was measured on a calibrated balance-beam scale to the nearest 0.1 kg. Height was measured at baseline, with a stadiometer to the nearest 0.5 cm.

Participants completed self-report and interview-based psychological assessments at baseline, midpoint (week 12), and following the 24-week double-blind treatment. Quality of life was measured by the Impact of Weight on Quality of Life-Lite total score (30) . The total score of this 31-item measure was calculated from the 74-item Impact of Weight on Quality of Life questionnaire and evaluated the domains of work, public distress, sexual life, physical function, and self-esteem.

Problematic eating attitudes and behaviors (also called eating pathology) were measured using the Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire (31) , designed to measure the following three dimensions of eating pathology: cognitive restraint, disinhibition, and hunger. Global improvement was rated by the investigator and participant on a 7-point scale (very much improved, improved, slightly improved, no change, slightly worse, worse, very much worse).

The following safety measures were assessed: adverse events, clinical laboratory data, physical examination findings, and vital signs. Adverse events were obtained through spontaneous participant reports and by open-ended inquiries by investigators.

Statistical Analyses

The primary outcome measure was the change from baseline in frequency of binge eating episodes (binges/week), defined as the mean number of binges per week in 2-week intervals. If the visit interval was less than 2 weeks, the mean number of binges per week was estimated based on the number of binge days in the interval since the last visit.

At the monthly visits in weeks 8–24 of double-blind treatment, the number of binge episodes was recorded for the entire preceding 28-day period, divided into two 2-week intervals. Secondary outcome measures included the change from baseline in frequency of binge days (or mean days per week when the participant had one or more binges), weight, body mass index, global improvement, Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire, and Impact of Weight on Quality of Life-Lite.

Response categories were tabulated based on the percentage decrease in frequency of binges from baseline (the period 2 weeks before double-blind treatment initiation) to endpoint (the final 2 weeks of treatment), which were defined as follows: complete=cessation of binges; marked=75% to <100% decrease; moderate=50% to <75% decrease; and none=<50% decrease. We also assessed the outcome of ≥5% decrease in weight from baseline. A ≥5% decrease in body weight is considered to be clinically significant because of the association with improvements in medical complications of obesity (32) .

Sample-size calculations, performed prior to the study, were based on detecting differences in the frequency of binges (median changes from baseline) for placebo and sibutramine participants. If we assume that a participant in the sibutramine group has a 61% greater chance of reducing his or her frequency of binges than a participant in the placebo group, then the required sample size—with 90% power at the 0.049 significance level—is 150 per group (31) .

We compared the baseline characteristics of each group using Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and the t test for continuous variables. We calculated adherence to treatment, based on the number of capsules returned at each visit, as the number of capsules taken divided by the number of days in the study × 100%.

The primary analysis of efficacy for continuous measures was analysis of variance (ANOVA), with terms for treatment and center, to assess differences between treatment groups in the change from baseline to endpoint (for frequency of binges and frequency of binge days, we transformed the frequencies during the 14 days before baseline and before endpoint into ranks to stabilize the variance and then analyzed the changes from baseline in those ranks) using the last observation carried forward. The primary analysis for global improvement and response categories was the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test, stratified by center for endpoint values using the last observation carried forward. The primary analysis for ≥5% reduction in weight was Fisher’s exact test using the last observation carried forward (33) .

We also performed several secondary analyses. For frequency of binges, frequency of binge days, weight, and body mass index, we used a longitudinal analysis comparing the rate of change of the outcome during the treatment period between groups. The difference in rate of change was estimated by random regression methods (34) as used in previous binge eating disorder studies (8 , 10 , 13 , 15 , 18 – 21) . The model for the mean of the outcome included terms for treatment, time, treatment-by-time interaction, and center. Time was modeled as a continuous variable, expressed as log (weeks +1). For the analyses of frequency of binges and frequency of binge days, we used the logarithmic transformations log (binges/week +1) and log (binge days/week +1), respectively, to normalize the data and stabilize the variance. To account for the correlation of observations within participants, we used SAS procedure MIXED with a first-order antedependence covariance structure. The longitudinal analyses used all available observations from all time points from all participants who completed a baseline evaluation.

For frequency of binges and weight, we also used change scores from baseline to endpoint using the baseline value carried forward, for which the difference between groups was assessed by ANOVA with terms for treatment and center. For response categories, we applied the same analysis described above, only substituting the baseline value carried forward for the last observation carried forward. We calculated effect sizes for the primary analysis of binges per week and weight using Cohen’s d (35) . In addition, for the frequency of binges we used Poisson regression, with terms for treatment and center, to analyze the change from baseline to endpoint using the last observation carried forward. Finally, we performed a Spearman rank correlation to assess the association between the change in frequency of binges from baseline to week 24 and the change in weight from baseline using completers.

We evaluated the differences between groups in the incidence of treatment-emergent adverse events using Fisher’s exact test. Alpha was 0.05, two-tailed.

Results

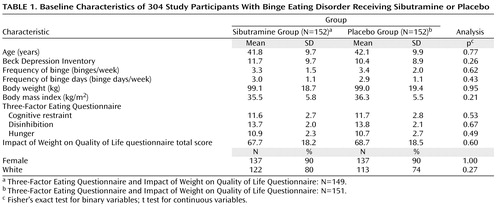

Overall, 543 participants entered the placebo lead-in period, of whom 239 discontinued prior to random assignment (147 were classified as placebo responders and 92 discontinued for other reasons); 304 participants who met the entry criteria were randomly assigned to sibutramine (N=152) or placebo (N=152) (see Figure 1 in the data supplement accompanying the online version of this article for disposition of study participants). At baseline, there were no significant differences between the treatment groups in demographic or clinical variables ( Table 1 ). The first participant was treated on March 24, 2000, and the last participant was treated on April 22, 2001.

At least one postrandomization efficacy measure was obtained on 289 participants (sibutramine: N=150; placebo: N=139); 50 (32.9%) of 152 participants in the sibutramine group and 65 (42.8%) of 152 participants in the placebo group did not complete all 24 weeks of treatment (Fisher’s exact test, two-tailed, p=0.10). The reasons for withdrawal were as follows: adverse events (sibutramine: N=10; placebo: N=6); lack of efficacy (sibutramine: N=3; placebo: N=7); nonadherence with the protocol (sibutramine: N=5; placebo: N=4); withdrawal of consent (sibutramine: N=13; placebo: N=24); administrative reasons (sibutramine: N=0; placebo: N=2); and loss to follow-up (sibutramine: N=19; placebo: N=22). Dropouts did not differ significantly from completers on any of the baseline characteristics listed in Table 1 .

Mean adherence was 76.2% in the sibutramine treatment group and 82.6% in the placebo treatment group; 65.1% of participants in the sibutramine group and 69.1% in the placebo group were >90% adherent.

The mean frequency of binges decreased over the 24-week study period in both treatment groups, but more so in the sibutramine group ( Figure 1 ). Mean weight was reduced considerably over this period in the sibutramine group but not in the placebo group ( Figure 2 ).

The primary efficacy analysis showed that participants receiving sibutramine had a significantly reduced frequency of binges compared with participants receiving placebo ( Table 2 ), with an effect size of 0.46. Participants receiving sibutramine experienced a mean reduction in the frequency of binges of 2.7 binges/week (SD=1.7) from baseline to endpoint, whereas those receiving placebo experienced a mean reduction of 2.0 binges/week (SD=2.3). Sibutramine was also associated with a significantly greater improvement than placebo for the following variables: frequency of binge days, weight (effect size=0.87), body mass index, and percentage change from baseline in weight and two Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire subscales ( Table 2 ). There was no significant difference between groups in the change in Impact of Weight on Quality of Life-Lite scores ( Table 2 ).

In examining categorical outcomes at week 24, sibutramine was associated with a significantly higher level of global improvement in investigator and participant ratings relative to placebo (p<0.001 for both last observation carried forward and baseline value carried forward analyses). Investigator ratings were “improved” or “very much improved” for 82.2% of the sibutramine group and 58.6% of the placebo group, and participant ratings were “improved” or “very much improved” for 80.2% of the sibutramine group and 56.3% of the placebo group. Sibutramine was also associated with a significantly higher level of response than placebo (p<0.001 for both last observation carried forward and baseline value carried forward analyses [ Figure 3 ]), with the following percent abstinent from binges: 58.7% (last observation carried forward) and 44.1% (baseline value carried forward) for sibutramine participants and 42.8% (last observation carried forward) and 30.3% (baseline value carried forward) for placebo participants. Finally, we observed ≥5% decrease of weight in 56 (37.3%) of 150 participants in the sibutramine group compared with only 13 (9.4%) of 139 in the placebo group (p<0.001).

a p<0.001 vs. placebo.

In the longitudinal analysis, sibutramine was associated with significant decreases in the frequency of binges, frequency of binge days, weight, and body mass index ( Table 2 ). In the baseline value carried forward analysis, sibutramine was associated with a significant decrease in the frequency of binges (F=6.58, df=1, 285, p=0.011) and weight (F=23.4, df=1, 285, p<0.001). In the Poisson regression, sibutramine was associated with a significant decrease in the frequency of binges (coefficient=–0.064, SE=0.012, z=–4.98, p<0.001).

Participants receiving sibutramine experienced a mean body weight loss of 4.3 kg (SD=4.8) from baseline to endpoint, whereas those receiving placebo experienced a mean weight loss of 0.8 kg (SD=3.5). Among participants who completed 24 weeks of treatment, the corresponding weight losses were 5.2 kg (SD=5.4) and 1.2 kg (SD=4.1), respectively. Among completers, weight loss since baseline was significantly correlated with percentage reduction in binge frequency at week 24 (r s =0.25, p<0.001).

For comparisons on measures of binge eating, weight, and body mass index using ANOVA or longitudinal analysis, we tested for overall site-by-treatment effect interaction and found no significant interactions, indicating that there was no evidence for a lack of homogeneity of effects across sites.

Adverse events occurring in ≥5% of participants receiving sibutramine or placebo are presented in Table 1 of the data supplement accompanying the online version of this article. Compared with placebo, sibutramine treatment was associated with significantly higher incidence of headache, dry mouth, constipation, insomnia, and dizziness (see Table 1 in the online data supplement). We observed statistically significant differences between the sibutramine and placebo treatment groups in the mean change from baseline to week 24 (last observation carried forward) for systolic blood pressure (sibutramine group: mean=2.0 [SD=10.7]; placebo group: mean=–1.3 [SD=12.1], p=0.012), diastolic blood pressure (sibutramine group: mean=2.0 [SD=8.5]; placebo group: mean=–0.8 [SD=8.7], p=0.006), and pulse (sibutramine group: mean=3.6 [SD=10.1]; placebo group: mean=–0.4 [SD=9.0], p<0.001). We observed no clinically significant differences between groups in hematology or blood chemistry measures.

Discussion

This multicenter trial replicated the findings of earlier small-scale controlled trials of sibutramine in individuals with binge eating disorder (15 , 16) . Sibutramine was found to be more effective than placebo in decreasing binge eating and reducing weight. Effect sizes for binge eating were moderate, and effect sizes for weight loss were large. In addition, sibutramine conferred beneficial effects on eating pathology and indices of global improvement. In general, the medication was well tolerated.

The placebo response rate in this trial was considerable. In the single-blind phase, 32.5% of participants were classified as placebo responders. In the double-blind phase, 42.8% of individuals in the placebo group were abstinent from binge eating using the last observation carried forward. These rates are similar to the mean placebo response rates for other major psychiatric illnesses (36 , 37) and consistent with the mean placebo response in other pharmacological studies of binge eating disorder (38) . Nonetheless, the following two features of our design may have increased the placebo response: 1) during the single-blind phase, participants received psychoeducation on changing dietary and physical activity behaviors, and 2) during the trial, participants maintained a diary monitoring the frequency of and food intake during binge eating episodes. These components have been shown to impact binge eating and body weight (22 , 39) . Nonspecific treatment effects may also have had an impact on the measurement of placebo response, along with other factors such as expectation effects and regression to the mean (36 , 37) .

Dropout rates in this trial were substantial (38% overall). Although most dropouts were not due to adverse events, the reports of dropouts resulting from adverse events in both treatment groups might possibly represent an underestimate if some discontinuations due to “loss to follow up” were actually related to adverse events. It is likely that the length of treatment had an impact on the dropout rate in this study, since the 24-week duration was twice as long as the majority of previous pharmacological trials of binge eating disorder. To address missing data in our study, the analyses of binge eating and weight were threefold (last observation carried forward, baseline value carried forward, longitudinal analysis); each analysis yielded a similar pattern of findings. Note that unlike the last observation carried forward and baseline value carried forward, the longitudinal analysis does not make the assumption that the data are missing completely at random, and thus it probably represents the most valid analysis.

The results of this trial confirm and extend previous work in this area, including studies of sibutramine (15 , 16) and other medications (8 – 14 , 17 – 21 , 38) . With different study designs, comparisons among trials are limited; nevertheless, changes in binge eating in this trial were of similar magnitude to those reported previously. It is noteworthy that many previous trials in binge eating disorder have shown limited impact on reducing weight, even when subjects achieved substantial changes in binge eating. To achieve weight loss in association with a reduction in binge eating episodes is therefore notable, particularly since weight loss is an important goal for individuals seeking treatment (40) .

There are several limitations to this trial that we should consider. First, the lack of a follow-up assessment prevented us from determining the persistence of changes following the discontinuation of medication. Second, although Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire scores were available to assess eating pathology, more extensive data on various aspects of eating disorder cognitions, such as overconcern with shape and weight, would have been useful. Third, strict entry criteria for the study (specifically a body mass index <45 and no comorbid psychiatric illness) may have excluded participants who had a poorer prognosis because of high levels of obesity or psychiatric comorbidity. Fourth, it may be that prolonged observation could reveal gradual diminishment of weight loss effects, which has been observed with many weight loss trials. Finally, some participants in the sibutramine group experienced small but significant increases in pulse and blood pressure during the study, consistent with those previously reported in obese patients and included in the label (23) . Since the lower dose of sibutramine (10 mg) has been shown to reduce the occurrence of such effects and has similar positive effects on body weight in studies of obese subjects (22 , 25) , it is possible that this lower dose of sibutramine may reduce these minor cardiovascular effects and still retain the beneficial effects on binge eating and weight in subjects with binge eating disorder.

In summary, the results of this placebo-controlled trial of sibutramine for binge eating disorder demonstrate good tolerability and clinically significant effects on binge eating and body weight over a 24-week period.

1. Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope HG Jr, Kessler RC: The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biol Psychiatry 2007; 61:348–358Google Scholar

2. National Task Force on the Prevention and Treatment of Obesity: Overweight, obesity, and health risk. Arch Int Med 2000; 160:898–904Google Scholar

3. Wilfley DE, Wilson GT, Agras WS: The clinical significance of binge eating disorder. Int J Eat Disord 2003; 34(suppl):S96–S106Google Scholar

4. National Institute for Clinical Excellence: Clinical Guidelines for Eating Disorders: Core Interventions in the Treatment and Management of Anorexia Nervosa, Bulimia Nervosa and Related Eating Disorders. London, NICE, 2004Google Scholar

5. Wilfley DE, Welch RR, Stein RI, Spurrell EB, Cohen L, Saelens BE, Dounchis JZ, Frank MA, Wiseman CV, Matt GE: A randomized comparison of group cognitive-behavioral therapy and group interpersonal psychotherapy for the treatment of binge eating disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2002; 59:713–721Google Scholar

6. Devlin MJ, Goldfein JA, Petkova E, Jiang H, Raizman PS, Wolk S, Mayer L, Carino J, Bellace D, Kamenetz C, Dobrow I, Walsh BT: Cognitive behavioral therapy and fluoxetine as adjuncts to group behavioral therapy for binge eating disorder. Obes Res 2005; 13:1077–1088Google Scholar

7. Grilo CM, Masheb RM: A randomized controlled comparison of self-help cognitive behavioral therapy and behavioral weight loss for binge eating disorder. Behav Res Ther 2005; 43:1509–1525Google Scholar

8. Hudson JI, McElroy SL, Raymond NC, Crow S, Keck PE, Carter WP, Mitchell JE, Strakowski SM, Pope HJ, Coleman B, Jonas J: Fluvoxamine in the treatment of binge-eating disorder: a multicenter placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:1756–1762Google Scholar

9. Pearlstein TB, Spurell EB, Hohlstein LA, Gurney V, Read J, Fuchs C, Keller MB: A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of fluvoxamine in binge eating disorder: a high placebo response. Arch Womens Ment Health 2003; 6:147–151Google Scholar

10. McElroy SL, Casuto LS, Nelson EB, Lake KA, Soutullo CA, Keck PE, Hudson JL: Placebo-controlled trial of sertraline in the treatment of binge eating disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:1004–1006Google Scholar

11. Arnold LM, McElroy SL, Hudson JL, Welge JA, Bennett AJ, Keck PE: A placebo-controlled, randomized trial of fluoxetine in the treatment of binge-eating disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2002; 63:1028–1033Google Scholar

12. Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Wilson GT: Efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy and fluoxetine for the treatment of binge eating disorder: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled comparison. Biol Psychiatry 2005; 57:301–309Google Scholar

13. McElroy SL, Hudson JI, Malhorta S, Welge JA, Nelson EB, Keck PE Jr: Citalopram in the treatment of binge-eating disorder: a placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry 2003; 64:807–813Google Scholar

14. Stunkard AJ, Berkowitz R, Tanrikut C, Reiss E, Young L: D-fenfluramine treatment of binge eating disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:1455–1459Google Scholar

15. Appolinario JC, Bacaltchuk J, Sichieri R, Claudino AM, Godoy-Matos A, Morgan C, Zanella MT, Coutinho W: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of sibutramine in the treatment of binge-eating disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003; 60:1109–1116Google Scholar

16. Milano W, Petrella C, Casella A, Capasso A, Carrino S, Milano L: Use of sibutramine, an inhibitor of the reuptake of serotonin and noradrenaline, in the treatment of binge eating disorder: a placebo-controlled study. Adv Ther 2005; 22:25–31Google Scholar

17. Golay A, Laurent-Jaccard A, Habicht F, Gachoud J, Chabloz M, Kammer A, Schutz Y: Effect of orlistat in obese patients with binge eating disorder. Obes Res 2005; 10:1701–1708Google Scholar

18. McElroy SL, Arnold LM, Shapira N, Keck PE, Rosenthal N, Karim M, Kamin M, Hudson JI: Topiramate in the treatment of binge eating disorder associated with obesity: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry 2003; 160:255–261Google Scholar

19. McElroy SL, Hudson JI, Capece JA, Beyers K, Fisher AC, Rosenthal NR: Topiramate for the treatment of binge eating disorder associated with obesity: a placebo-controlled study. Biol Psychiatry 2007; 61:1039–1048Google Scholar

20. McElroy SL, Kotwal R, Guerdjikova A, Welge JA, Nelson EB, Lake KA, Keck PE Jr, Hudson JI: Zonisamide in the treatment of binge eating disorder with obesity: a placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry 2006; 67:1897–1906. Erratum in: J Clin Psychiatry 2007; 68:172Google Scholar

21. McElroy SL, Guerdjikova A, Kotwal R, Welge JA, Nelson EB, Lake KA, D’Alessio D, Keck PE Jr, Hudson JI: Atomoxetine in the treatment of binge eating disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2007; 68:390–398Google Scholar

22. Wadden TA, Berkowitz RI, Womble LG, Sarwer DB, Phelan S, Cato RK, Hesson LA, Osei SY, Kaplan R, Stunkard AJ: Randomized trial of lifestyle modification and pharmacotherapy for obesity. N Engl J Med 2005; 353:2111–2120Google Scholar

23. Meridia (sibutramine hydrochloride monohydrate): Chicago, Abbott Laboratories (package insert), 2004Google Scholar

24. Yanovski SZ, Yanovski JA: Obesity. N Engl J Med 2002; 346:591–602Google Scholar

25. Arterburn DE, Crane PK, Veenstra DL: The efficacy and safety of sibutramine for weight loss: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med 2004; 164:994–1003Google Scholar

26. Mitchell JE, Gosnell BA, Roerig JL, de Zwaan M, Wonderlich SA, Crosby RD, Burgard MA, Wambach BN: Effects of sibutramine on binge eating, hunger, and fullness in a laboratory human feeding paradigm. Obes Res 2003; 11:599–602Google Scholar

27. Shape Up America: On Your Way to Fitness (available at http://www.shapeup.org/publications/on.your.way.to.fitness/index.html)Google Scholar

28. Fairburn CG, Cooper Z: The Eating Disorder Examination, Twelfth Edition, in Binge Eating: Nature, Assessment, and Treatment. Edited by Fairburn CG, Wilson GT. New York, Guilford Press, 1993, pp 317–356Google Scholar

29. Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Lozano-Blanco C, Barry DT: Reliability of the eating disorder examination in patients with binge eating disorder. Int J Eating Disord 2004; 35:80–85Google Scholar

30. Kolotkin RL, Crosby RD, Kosloloski KD, Williams GR: Development of a brief measure to assess quality of life in obesity. Obesity Res 2001; 9:102–111Google Scholar

31. Stunkard AJ, Messick S: Eating Inventory Manual. San Antonio, Tex, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1988Google Scholar

32. Goldstein DJ: Beneficial health effects of modest weight loss. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 1992; 6:397–415Google Scholar

33. Noether GE: Sample size determination for some common nonparametric tests. J Am Stat Assoc 1987; 82:645–647Google Scholar

34. Fitzmaurice GM, Laird NM, Ware JH: Applied Longitudinal Analysis. Hoboken, NJ, Wiley, 2004Google Scholar

35. Cohen J: Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, Second Editon. Hillsdale, NJ, Lawrence Erlbaum, 1988Google Scholar

36. Charney DS, Nemeroff CB, Lewis L, Laden SK, Gorman JM, Laska EM: National Depressive and Manic-Depressive Association consensus statement on the use of placebo in clinical trials of mood disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2002; 59:262–270Google Scholar

37. Walsh BT, Seidman SN, Sysko R, Gould M: Placebo response in studies of major depression. JAMA 2002; 287:1840–1847Google Scholar

38. Carter WP, Hudson JI, Lalonde J, Pindyck L, McElroy SL, Pope HG Jr: Pharmacologic treatment of binge eating disorder. Int J Eating Disord 2003; 34:S74–S88Google Scholar

39. Wonderlich SA, de Zwaan M, Mitchell JE, Peterson CB, Crow SJ: Psychological and dietary requirements for binge eating disorder: conceptual implications. Int J Eat Disord 2003; 24(suppl):558–573Google Scholar

40. Brody ML, Masheb RM, Grilo CM: Treatment preferences of patients with binge eating disorder. Int J Eat Disord 2005; 37:452–356Google Scholar