Prognostic Variables at Intake and Long-Term Level of Function in Schizophrenia

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study assessed the relationship between symptoms and cognitive measures at intake and functional outcome 2–8 years later (average 3 years) in first-episode and previously treated schizophrenia patients. METHOD: A composite cognitive score was assessed at intake to determine the influence of cognition on later functional outcome. At intake and follow-up, positive and negative symptoms were assessed with the Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms and the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms, and affective symptoms were assessed with the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale. Level of function in seven domains (social function, occupational function, independent living, symptom severity, fullness of life, extent of psychiatric hospitalization, and overall level of function) at intake and follow-up was assessed with the Strauss-Carpenter Level of Function scale. The contributions of sex, education, and duration of illness to functional outcome were also examined. RESULTS: The results indicated that symptoms at intake had distinct patterns of prognostic significance for functional outcome in previously treated patients, compared with first-episode patients. In addition, male and female patients differed in the degree to which initial symptoms were correlated with later function. CONCLUSIONS: Initial level of function, symptoms, sex, education, and duration of illness are all important predictors for functional outcome in patients with schizophrenia.

Schizophrenia affects behavior, perception, and cognition, with resulting impairments in multiple functional domains. The severity and chronicity of schizophrenia have stimulated examination of sociodemographic and clinical variables at presentation as predictors of outcome. Although this research has yielded several consistent conclusions, inconsistencies are also apparent. Several studies suggested that illness course differs between men and women (1–3), but other studies have found no difference (4–6). Because similar measures may have different predictive values depending on the stage of illness, some inconsistencies may relate to the composition of samples that included patients with new-onset schizophrenia as well as patients with chronic schizophrenia.

Research with first-episode patients has received increased attention in neurobiology (7, 8) and treatment research (9, 10). Yet only a few studies have examined differences in prognostic factors between first-episode and previously treated patients (11, 12). These studies found both similarities and differences between these groups in presentation and outcome. Positive symptoms in first-episode patients and previously treated patients were found to improve at 6-month, 1-year, and 2-year follow-up, but only previously treated patients showed a reduction in negative symptoms (11, 13, 14). It is unclear whether the reduction in negative symptoms for previously treated patients reflects a later stage of illness or whether negative symptoms are less prominent at onset in first-episode patients. This uncertainty highlights the value of evaluating stage of illness in the assessment of the prognostic significance of symptoms and other predictors.

In some studies, symptom severity at intake was correlated with symptom-based and quality-of-life outcomes in first-episode patients (4, 15), yet other researchers failed to find such correlations (16). For example, positive symptom severity at intake has been correlated with poor outcome at 1 year (15) and with better outcome at long-term follow-up (23 years) but not at 2–8 years (17). Negative symptoms have also been assessed in first-episode patients, with mixed results; negative symptoms were found to correlate with poor functioning at intake and 2 years (18) but not 1-year follow-up (15).

In a 5-year study of first-episode patients, depressive symptoms, assessed with the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D), were found at intake in 75% of the patients (19). Furthermore, depressive symptoms were correlated with both positive and negative symptoms and resolved as psychotic symptoms resolved. However, studies examining the significance of depressive symptoms in first-episode patients have yielded mixed results. Depressive symptoms were poorly correlated with 1-year outcome in one study (15), but in another study, depressive symptoms predicted early remission, whereas flat affect predicted longer episodes and shorter remissions (14).

Thus, there are inconsistencies in the findings of outcome studies investigating the role of sex, age, and symptoms, as well as the differences between first-episode and previously treated schizophrenia. The current study was designed to address some inconsistencies through assessment of functional outcome among first-episode and previously treated men and women with schizophrenia who were prospectively recruited over a 20-year period, rigorously characterized, and followed for an average of 3 years. Our goal was to examine how the relationship between symptoms at intake and later functional outcome varies with treatment status and sex. Seven domains were assessed with the nine-item Strauss-Carpenter Level of Function scale (20, 21) concurrently with measurement of symptoms at intake and follow-up. The Level of Function scale is used to measure social, occupational, and independent living domains. In addition, it is used to assess symptom severity, fullness of life, extent of psychiatric hospitalization, and overall level of function. Our goal was to increase the understanding of how demographic and clinical data at intake predict later function in schizophrenia. Such knowledge can help clinicians, patients, and family members gauge long-term prognosis and expectations based on patients’ presentation at intake.

Method

Subjects

A total of 208 patients were recruited by the Schizophrenia Research Center at the University of Pennsylvania and completed intake procedures. Of these, 110 patients did not have follow-up data available for the specified interval. Therefore, 98 participants were included in this study.

All participants received a diagnosis of schizophrenia after a comprehensive intake examination. Inclusion in the current analyses was limited to patients who completed assessment scales at 6-month intervals and for whom outcome data from follow-up evaluations were available for 2–8 years (average 3 years). Intake protocols included a 1–2-hour psychiatric evaluation by a research psychiatrist, standardized interview with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (22), and consensus diagnosis by a team of psychiatrists and psychologists (23). Before the consensus diagnosis and interim assessments, we obtained medical records from physicians who previously treated the patients, patients’ hospital records, and collateral information from family members. All participants had stable residence in an independent living situation, group/boarding home, or family home. No participants lived in long-term psychiatric facilities. Approximately one-half (N=45 of 98) of the participants received clinical care at the University of Pennsylvania. After completion of the intake assessment, patients were followed longitudinally as clinically indicated, enabling detailed follow-up during illness progression. Clinical care was based on best clinical practices, and pharmacological and psychoeducational treatments were provided free of charge if needed. Medical, neurological, and psychiatric evaluations were used to exclude all patients with history of substance abuse, hypertension, metabolic disorders, neurological disorders, or head trauma with loss of consciousness (23). Thus, this cohort was limited to patients with pure schizophrenia with the exclusion of potentially complicating factors. All patients provided informed consent to participate.

Assessment Scales

The patients were evaluated by trained research coordinators, physicians, or psychologists with an overall 0.90 level of reliability (23) for the Scale for Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS) (24), Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS) (25), HAM-D (26), and the Level of Function scale (20, 21). In addition, a cognitive composite z score based on measures of abstraction, attention, verbal memory, spatial memory, language, and spatial processing within 4 months of intake was included for each patient (27). Data on the level of education for patients and parents, age at onset of illness, and duration of illness were recorded. Age at onset was defined as the age at emergence of psychotic symptoms in the context of functional decline. Duration of illness was defined as age at intake minus age at onset. Patients were administered the assessment scales at 6-month intervals, and we examined outcome data from follow-up evaluations performed between 2 and 8 years after intake (average 3 years).

Patient Groups

The first-episode patients were neuroleptic naive, and the previously treated patients had received antipsychotics. Eighteen first-episode female patients, 27 first-episode male patients, 22 previously treated female patients, and 31 previously treated male patients were included in the study.

Data Analysis

The Level of Function scale consists of nine items, each of which is scored on a scale from 0 to 4. Items are designed so that low numbers indicate impaired function and high numbers indicate high function. Several items are stated in the negative (e.g., item 1 measures duration of nonhospitalization) to retain the convention of low scores corresponding to low function (low duration of nonhospitalization = high duration of hospitalization). The nine Level of Function scale items measure duration of nonhospitalization, quantity of social contacts, quality of social contacts, quantity of useful work, quality of useful work, absence of symptoms, ability to meet own basic needs, fullness of life, and overall level of function.

Our goal was to examine how the relationship between symptoms and cognitive measures at intake and long-term function varies by previous treatment status and sex. Thus, linear regression analyses were performed to assess the relationships between the total symptom and composite cognitive scores at intake and total level of function at follow-up. Interactions were also assessed to test if the relationship between the change in total symptom scores at intake and level of function score differed by sex and treatment status. We used stepwise regression analysis with backward elimination; the p value to remove was set at 0.01. We examined HAM-D, SANS, and SAPS scores at follow-up in a similar manner. Because the distributions for the HAM-D, SANS, and SAPS total scores were right-skewed, a square-root transformation was used for each of these outcome variables to achieve approximate normality.

In addition, ordinal logistic regression models were used to examine the relationships between each measure at intake and scores on each of the individual Level of Function scale items at follow-up. Again, interactions were assessed to test whether these relationships differed by gender and treatment status, and stepwise regression with backward elimination was used to derive final multivariate models. The results are presented as odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals.

To examine the long-term stability of the Level of Function scale, HAM-D, SANS, and SAPS scores, linear regression analyses were performed with effects for time period (intake versus follow-up), sex, and treatment status (first episode versus previously treated). Each two-way and three-way interaction between sex, treatment status, and time was included to test whether any changes over time differed by sex and/or treatment status. These models were fit by using generalized estimating equations with a compound symmetry correlation structure to account for the nonindependence or clustering of data from the two assessments for each patient (intake and follow-up).

Pearson’s chi-square tests were used to compare medication use (atypical antipsychotic medication, typical antipsychotic medication, or no medication) at follow-up evaluation among patients grouped by sex and treatment status. Fisher’s exact test was used to compare the four-level group variable. The effect sizes for differences between patients taking atypical antipsychotic medication, typical antipsychotic medication, or no medication at follow-up were calculated for the Level of Function scale, HAM-D, SANS, and SAPS scores at follow-up.

Wilcoxon rank-sum tests were conducted to assess differences in demographic characteristics between groups at intake. Because of the large number of variables under consideration, only associations reaching statistical significance at the 1% level were considered statistically significant throughout all analyses (SAS version 8.2, SAS Institute, Cary, N.C.).

Results

Participant Characteristics

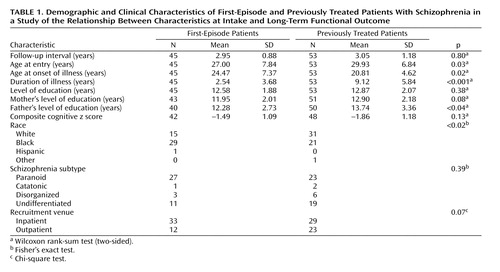

Demographic characteristics for the study participants, including follow-up interval, age at intake, age at onset of illness, duration of illness, race, schizophrenia subtype, inpatient/outpatient status at intake, composite cognitive z score, level of education, and parents’ level of education, are summarized in Table 1. Symptom, function, and cognitive scores at intake were compared between patients with and without follow-up data. There was no difference between these groups for either Level of Function scale total score (t=0.22, df=205, p=0.82) or cognitive score (t=0.26, df=180, p=0.79) at intake. However, patients who did not complete follow-up measures had significantly lower SAPS (t=–5.02, df=206, p<0.001), SANS (t=–3.41, df=201, p≤0.001), and HAM-D (t=–2.08, df=203, p<0.04) scores at intake, suggesting that the study cohort comprised a relatively ill population.

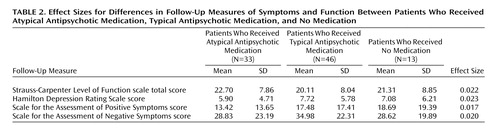

Dates of entry ranged from February 1983 to February 2001. Because patients entered the study during years before and after the period when atypical antipsychotic medications were introduced, we evaluated the effect size of the difference between medication type groups for each total score at follow-up. Of the patients for whom follow-up data were available, 33 received atypical antipsychotic medication, 46 received typical antipsychotic medication, and 13 did not take medications. There were no effects of sex (χ2=0.19, df=2, p=0.91) or treatment status (χ2=1.86, df=2, p=0.24) on the proportion of patients in each medication class at follow-up. Follow-up scores on the Level of Function scale, HAM-D, SAPS, and SANS were also compared between patients who received atypical antipsychotic medication, typical antipsychotic medication, or no medication. Effect sizes for differences in total scale scores by medication class ranged from 0.017 to 0.023 (Table 2).

Prognostic Variables

The group means and standard deviations for scores on individual items on the Level of Function scale, HAM-D, SANS, and SAPS at intake and follow-up are shown in Data Supplement 1, which is available with the online version of this article at http://ajp.psychiatryonline.org.

Stability of Measures

Linear regression analyses using generalized estimating equations were conducted to assess the long-term stability of intake scores on the Level of Function scale, HAM-D, SANS, and SAPS. Scores on all four scales changed significantly between intake and follow-up. On average, the Level of Function scale total score at intake (mean=16.77, SD=7.64) increased by 4.29 points by follow-up (mean=21.06, SD=8.01). HAM-D, SANS, and SAPS scores were transformed for normality by using the square root transformation. Similarly, the average HAM-D score on the square root scale decreased by 0.98 point over time, such that transformed HAM-D mean scores went from 12.15 (SD=6.25) to 7.00 (SD=5.56). The mean SANS score on the square root scale decreased by 1.40 points over time, going from 46.84 (SD=24.97) at intake to 31.68 (SD=21.97) at follow-up. The average SAPS score on the square root scale decreased by 2.90 points, from a mean of 42.63 (SD=20.20) at intake to 16.53 (SD=16.50) at follow-up. In addition, results of the generalized estimating equation analysis for the interactions showed that neither treatment status nor sex was a significant predictor of the stability of the scale scores over time. Duration of follow-up within the specified interval did not significantly affect any outcome measure.

Symptom Scales as Prognostic Variables

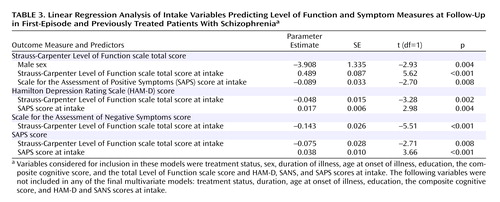

For each outcome prognostic measure considered here—total Level of Function scale score, HAM-D score, SANS score, and SAPS score—a model was constructed to determine the associated intake variables. The prognostic measures at intake considered for inclusion as covariates in these stepwise models were treatment status, sex, duration of illness, age at onset of illness, education, the composite cognitive score, and the total Level of Function scale score. Of the potential covariates, treatment status, duration of illness, age at onset of illness, education, the composite cognitive score, and HAM-D and SANS scores at intake were not significant and thus were not included in any of the final multivariate models. The results of these regression analyses are presented in Table 3. Considering the total Level of Function scale score at follow-up as the outcome measure, significant predictors were gender, total Level of Function scale score at intake, and SAPS score at intake, with higher levels of function at intake positively associated with level of function at follow-up. In addition, at follow-up, the total Level of Function scale score for male patients was on average 4 points less than that for female patients. Also, SAPS scores at intake were negatively associated with total Level of Function scale scores at follow-up. Considering the HAM-D score at follow-up as the outcome measure, significant predictors were total Level of Function scale score and SAPS score at intake, with higher levels of function at intake negatively associated with HAM-D scores at follow-up. Also SAPS scores at intake were positively associated with HAM-D scores at follow-up. Considering the SANS score at follow-up as the outcome measure, total Level of Function scale score at intake was the only predictor and was negatively associated with SANS scores at follow-up. Considering the SAPS score at follow-up as the outcome measure, significant predictors were total Level of Function scale score and SAPS score at intake, with higher levels of function at intake negatively associated with SAPS scores at follow-up. In addition, SAPS scores at intake were positively associated with SAPS scores at follow-up.

There were no associations of SANS or HAM-D scores at intake with either total symptom measures or total Level of Function scale scores at follow-up. Although composite cognitive scores were positively associated with total Level of Function scale scores at follow-up across all groups in the univariate model (t=2.01, df=1, p<0.05), this factor was not retained in the final multivariate model. Similarly, cognitive scores were negatively associated with SANS scores at follow-up in the univariate model (t=–3.08, df=1, p=0.003), but this association was not retained in the final multivariate model. Cognitive scores were not associated with either SAPS or HAM-D scores at follow-up.

Level of Function Scale Items

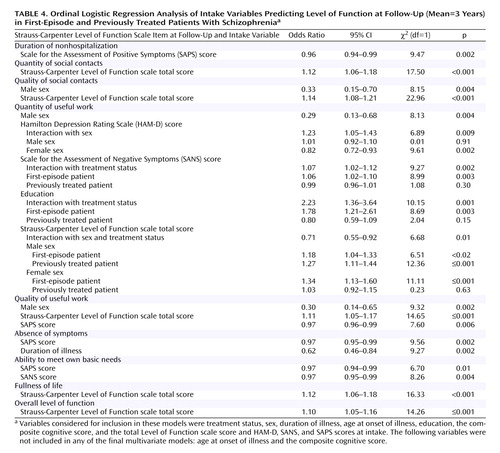

The results of an ordinal logistic regression analysis after backward elimination are summarized in Table 4. Treatment status, sex, duration of illness, age at onset of illness, education, the composite cognitive score, and the total Level of Function scale score, HAM-D score, SANS score, and SAPS score at intake were considered for inclusion in these models. Nonhospitalization scores at follow-up were negatively associated with SAPS scores at intake. Quantity of social contacts scores at follow-up were positively associated with Level of Function scale total scores at intake. Quality of social contacts scores at follow-up were significantly associated with sex and with Level of Function scale total scores at intake. At follow-up, male patients were three times less likely to have meaningful social relationships than were female patients.

For quantity of useful work, the ordinal logistic regression model identified six individual factors, as well as interaction effects. A main effect for sex suggested that male patients have lower odds of attaining a higher quantity of work, compared to female patients. After backward elimination, a significant interaction between gender and HAM-D scores emerged, indicating that the effect of HAM-D score on quantity of work differed for male and female patients. For women, HAM-D scores were negatively associated with quantity of work at follow-up. However, HAM-D scores at intake had no effect on the quantity of work at follow-up for male patients. In addition, there was an interaction between treatment status and SANS scores on this measure, that is, the effect of SANS scores on quantity of work differed for first-episode versus previously treated patients. Among first-episode patients, the amount of work at follow-up was positively associated with total SANS score at intake. However, among previously treated patients, total SANS scores at intake had no association with later quantity of work. There was also a two-way interaction between education and treatment status for quantity of work. For first-episode patients, quantity of useful work increased with an increase in level of education. For previously treated patients, level of education had no effect on later quantity of work. Results for a three-way interaction revealed that as Level of Function scale total scores at intake increased, quantity of work increased for all patients except previously treated female patients.

For quality of useful work, the ordinal logistic regression model identified three main effects. Female patients were three times more likely to be in a higher category for quality of useful work than were male patients. Quality of work at follow-up increased with higher total Level of Function scale scores at intake. In addition, quality of work at follow-up decreased with higher SAPS scores at intake.

Two main effects were identified for the Level of Function scale item measuring absence of symptoms. Higher SAPS scores at intake were associated with lower absence of symptoms scores at follow-up. In addition, longer duration of illness at intake was associated with lower absence of symptoms scores at follow-up. There were two main effects for the Level of Function scale item measuring ability to meet one’s own needs: higher SAPS and SANS scores at intake were associated with decreased ability to meet one’s own needs. For the fullness of life item, the model identified a main effect of total level of function at intake. Higher fullness of life scores at follow-up were associated with higher total Level of Function scale scores at intake. The model also revealed a main effect of Level of Function scale total scores at intake on overall level of function at follow-up. The composite cognitive score was significantly associated with scores for quantity of social contacts (χ2=3.91, df=1, p<0.05), quality of useful work (χ2=6.33, df=1, p<0.02), and ability to meet one’s own needs (χ2=6.15, df=1, p<0.02) at follow-up in the univariate models, but these relationships were not retained in the multivariate models.

Discussion

An extensive literature addresses factors that influence outcome in schizophrenia. However, there are inconsistencies in this literature, and prognostic variables that impact functional outcome in schizophrenia remain unclear. Many studies of outcomes in schizophrenia have indicated gender differences in social and symptom-related course (28). We augment previous literature by highlighting the effects on long-term level of function of sex, education, and duration of illness, as well as positive, negative, affective, and cognitive symptoms. The longitudinal design of this study adds a valuable perspective to existing cross-sectional studies on prediction of outcome.

Our results suggest that patients’ level of function at intake is a reliable predictor of later level of function. In addition, several symptom-related and demographic variables are good predictors of future level of function. Specifically, a higher overall level of function at follow-up is predicted by lower levels of positive, negative, and depressive symptoms at intake. This profile is reflected in greater fullness of life and better occupational and social interactions. Thus, patients who present with higher levels of positive, negative, or depressive symptoms at intake are expected to have a poorer prognosis than patients with lower levels of those symptoms. This finding is particularly relevant, as it suggests that the type of symptoms at intake is less important than the intensity of symptoms in predicting later level of function.

Although cognitive function at intake was associated with total Level of Function scale and SANS scores and scores on three Level of Function scale items in the univariate models, it was not associated with any outcome measure in the multivariate models. Therefore, the cognitive contribution to functional outcome was not retained after all of the other patient variables and scale scores were incorporated. Findings in several previous studies have suggested that specific cognitive domains are associated with long-term functional outcome (29, 30), and the lack of a relationship in our study may have resulted from our use of a composite cognitive z score rather than individual cognitive domain scores. Our approach was chosen to balance the large number of factors that were being assessed with the desire to include an overall measure of cognitive capacity that was comparable to the total scale scores obtained with use of the SAPS, SANS, HAM-D, and Level of Function scale. In addition, the large number of analyses performed suggests that our findings may be best viewed as exploratory and as requiring replication in other settings to confirm the hypotheses generated by the current work.

We found that a higher level of positive symptoms at intake was associated with a longer duration of hospitalization, increased overall symptoms, decreased ability to meet basic needs, and decreased quality of work later in life. It is surprising to note that sex was not an important modifier of this relationship. Previous studies that examined the relationship between positive symptoms at index admission and long-term outcome have focused primarily on previously treated patients. One study found a correlation of residual levels of both positive and negative symptoms after treatment with later levels of symptoms, function, and hospitalization (31). However, symptoms during a medication-free period were not correlated with either symptoms or function at follow-up. Similarly, poor treatment response at index evaluation has been correlated with symptom severity and social and occupational function at 1-year follow-up (13). Our data extended this work by suggesting that the relationship between positive symptom severity at intake and long-term follow-up does not differ by sex or previous treatment status.

As expected, negative symptoms at intake adversely affected later ability to meet one’s own needs. It is surprising to note that first-episode patients’ ability to find work was positively associated with negative symptoms at intake. This increase in quantity of work following greater negative symptoms at index evaluation may be due to the presence of secondary negative symptoms that resolve in response to treatment. An alternative explanation is that previously treated patients may not have shown such a relationship because their secondary negative symptoms had already responded to treatment, resulting in a purer estimate of primary negative symptoms at intake.

We also found that both sex and previous treatment status influenced the relationship between initial level of function and later quantity of work. Previously treated female patients were the only group in whom the quantity of work was not mediated by earlier level of function. This relationship was due to the high quantity of work among previously treated female patients with a low initial level of function, which left less capacity for incremental improvement. Sex of the participant also influenced the relationship between depressive symptoms at intake and later quantity of work such that higher levels of depressive symptoms resulted in decreased quantity of work only in women. This finding may reflect a greater range of affective expression among women with schizophrenia, as well as a higher quantity of work among women patients, relative to men, allowing greater variability in both dimensions.

Male patients were three times less likely than female patients to have meaningful social relationships. It is possible that male patients exhibit more socially unfavorable behaviors, contributing to a poorer social course, and that female patients tend to be cooperative and compliant, which might positively influence social course (28). In addition, estrogen may serve a functionally protective role by causing the illness to manifest at a later age in female patients, affording them greater opportunities to develop social and occupational skills (3, 28). As such, the sex of the patient appears to play an important role in long-term social and occupational relationships.

Other demographic variables, including level of education and duration of illness, also affected later level of function. Although first-episode patients showed a positive association between level of education and future quantity of work, this relationship was not apparent for previously treated patients. This finding suggests that the benefit of education for working that is found for first-episode patients is lost as the illness progresses. Longer duration of illness at intake also had a negative effect on overall symptoms at follow-up. Similar results were found in previous studies in which longer duration of illness was associated with more severe positive symptoms at 2 years, poorer social and occupational function before presentation for treatment, and poorer outcome at 1 and 3 years in first-episode and previously treated patients (11, 32). Similarly, our results are consistent with studies showing that a lag to treatment is an important determinant of time to remission and level of remission in schizophrenia (2).

One encouraging outcome of this study was that patients’ level of function increased over time; this change was also reflected in decreased levels of depressive, negative, and positive symptoms. It is interesting to note that our analyses suggest that neither sex nor treatment status altered the stability of the scale scores over time. This was true despite our finding that male patients had lower levels of function at follow-up than female patients. However, our interpretations have several limitations. The study participants included high-functioning patients with stable living arrangements in the community who were able to remain in longitudinal research protocols. Outcomes may also have been influenced by the psychiatric care that was available. All participants had access to continuous care in the Schizophrenia Research Center for as long as they wished, regardless of their financial status. Approximately one-half of the participants chose to receive care in this setting, which may not be representative of outpatient care in many communities and may bias the results. Also, the majority of patients came to our attention after either inpatient admission or entry/reentry into outpatient care. Although this study was not designed to examine the effects of therapeutic interventions, all participants remained in care and were followed throughout the study interval, which could account for the general improvement in all measures over time. Also, several Level of Function scale items (e.g., items measuring nonhospitalization, quantity of work, fullness of life, and overall level of function) lacked sufficient representation for the most impaired categories. Although it was advantageous to obtain prognostic indicators in a cohort of patients who were engaged in stable long-term care, this design feature may limit generalizability. For instance, the patients in our study were not frequently hospitalized, resulting in decreased variability on the Level of Function scale item measuring nonhospitalization. The study included a relatively large cohort of rigorously characterized patients for a longitudinal study, but even with 98 patients, our ability to detect some interactions was likely to have been limited due to lack of power.

This prospective longitudinal study included data collected over a long period of time. Although advantageous for prognostic analyses, the long study period presents the potential for time-related cohort effects, such as effects related to the introduction of newer medications during the study. However, the effect sizes for medication class were small for all outcome measures at follow-up, suggesting that medication class was not a significant confound.

In summary, our results suggest that level of function at intake is among the most important prognostic variables in analyses with a longitudinal prospective designs. Furthermore, analyses that incorporate the specific contributions of sex, treatment status, age, education, and length of illness are useful in assessing functional prognosis as well as symptom progression. Such comprehensive evaluations can help clinicians, patients, and family members have more informed expectations for long-term prognosis on the basis of presentation at intake.

|

|

|

|

Received Jan. 3, 2005; revision received March 18, 2005; accepted March 31, 2005. From the Division of Neuropsychiatry and Stanley Center for Experimental Therapeutics in Psychiatry, University of Pennsylvania. Dr. Siegel and Ms. Irani contributed equally to this work. Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. Siegel, Department of Psychiatry, University of Pennsylvania, Translational Research Laboratories, Rm. 2223, 125 S. 31st St., Philadelphia, PA 19104; [email protected] (e-mail).Supported by Stanley Medical Research Institute (S.J.S.) and NIMH grant MH-064045 (R.E.G.).Supplemental data from this study are reported in a table that accompanies the online version of this article.

1. Szymanski S, Lieberman JA, Alvir JM, Mayerhoff D, Loebel A, Geisler S, Chakos M, Koreen A, Jody D, Kane J, Woerner M, Cooper T: Gender differences in onset of illness, treatment response, course, and biologic indexes in first-episode schizophrenic patients. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:698–703Link, Google Scholar

2. Loebel AD, Lieberman JA, Alvir JM, Mayerhoff DI, Geisler SH, Szymanski SR: Duration of psychosis and outcome in first-episode schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:1183–1188Link, Google Scholar

3. Hambrecht M, Maurer K, Hafner H, Sartorius N: Transnational stability of gender differences in schizophrenia? an analysis based on the World Health Organization study on determinants of outcome of severe mental disorders. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 1992; 242:6–12Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Browne S, Clarke M, Gervin M, Waddington JL, Larkin C, O’Callaghan E: Determinants of quality of life at first presentation with schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry 2000; 176:173–176Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Ho B-C, Andreasen NC, Flaum M, Nopoulos P, Miller D: Untreated initial psychosis: its relation to quality of life and symptom remission in first-episode schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:808-815; correction, 2001; 158:986Google Scholar

6. Kendler KS, Walsh D: Gender and schizophrenia: results of an epidemiologically-based family study. Br J Psychiatry 1995; 167:184–192Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. McGlashan TH: Duration of untreated psychosis in first-episode schizophrenia: marker or determinant of course? Biol Psychiatry 1999; 46:899–907Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Thakore JH: Metabolic disturbance in first-episode schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry Suppl 2004; 47:S76-S79Google Scholar

9. Lieberman JA, Koreen AR, Chakos M, Sheitman B, Woerner M, Alvir JM, Bilder R: Factors influencing treatment response and outcome of first-episode schizophrenia: implications for understanding the pathophysiology of schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry 1996; 57(suppl 9):5-9Google Scholar

10. Wyatt RJ, Damiani LM, Henter ID: First-episode schizophrenia: early intervention and medication discontinuation in the context of course and treatment. Br J Psychiatry Suppl 1998; 172:77–83Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Szymanski SR, Cannon TD, Gallacher F, Erwin RJ, Gur RE: Course of treatment response in first-episode and chronic schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:519–525Link, Google Scholar

12. Lieberman JA, Alvir JM, Woerner M, Degreef G, Bilder RM, Ashtari M, Bogerts B, Mayerhoff DI, Geisler SH, Loebel A, Levy DL, Hinrichsen G, Szymanski S, Chakos M, Koreen A, Borenstein M, Kane JM: Prospective study of psychobiology in first-episode schizophrenia at Hillside Hospital. Schizophr Bull 1992; 18:351–371Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Gupta S, Andreasen NC, Arndt S, Flaum M, Hubbard WC, Ziebell S: The Iowa Longitudinal Study of Recent Onset Psychosis: one-year follow-up of first episode patients. Schizophr Res 1997; 23:1–13Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Eaton WW, Thara R, Federman E, Tien A: Remission and relapse in schizophrenia: the Madras Longitudinal Study. J Nerv Ment Dis 1998; 186:357–363Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Robinson DG, Woerner MG, Alvir JMJ, Geisler S, Koreen A, Sheitman B, Chakos M, Mayerhoff D, Bilder R, Goldman R, Lieberman JA: Predictors of treatment response from a first episode of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:544–549Link, Google Scholar

16. Lastra I, Vazquez-Barquero JL, Herrera Castanedo S, Cuesta MJ, Vazquez-Bourgon ME, Dunn G: The classification of first episode schizophrenia: a cluster-analytical approach. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2000; 102:26–31Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Jonsson H, Nyman AK: Prediction of outcome in schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1984; 69:274–291Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Addington D, Addington J, Patten S: Depression in people with first-episode schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry Suppl 1998; 172:90–92Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Koreen AR, Siris SG, Chakos M, Alvir J, Mayerhoff D, Lieberman J: Depression in first-episode schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:1643–1648Link, Google Scholar

20. Strauss JS, Carpenter WT Jr: Prediction of outcome in schizophrenia, III: five-year outcome and its predictors. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1977; 34:159–163Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Strauss JS, Carpenter WT Jr: The prediction of outcome in schizophrenia, I: characteristics of outcome. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1972; 27:739–746Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Patient Edition (SCID-P), version 2. New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1996Google Scholar

23. Gur RE, Mozley PD, Resnick SM, Levick S, Erwin R, Saykin AJ, Gur RC: Relations among clinical scales in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1991; 148:472–478Link, Google Scholar

24. Andreasen NC: Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS). Iowa City, University of Iowa, 1984Google Scholar

25. Andreasen NC: Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS). Iowa City, University of Iowa, 1983Google Scholar

26. Hamilton M: Development of a rating scale for primary depressive illness. Br J Soc Clin Psychol 1967; 6:278–296Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Gur RC, Ragland JD, Moberg PJ, Bilker WB, Kohler C, Siegel SJ, Gur RE: Computerized neurocognitive scanning, II: the profile of schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology 2001; 25:777–788Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Hafner H: Gender differences in schizophrenia. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2003; 28(suppl 2):17-54Google Scholar

29. Harvey PD, Bertisch H, Friedman JI, Marcus S, Parrella M, White L, Davis KL: The course of functional decline in geriatric patients with schizophrenia: cognitive-functional and clinical symptoms as determinants of change. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2003; 11:610–619Medline, Google Scholar

30. Green MF: What are the functional consequences of neurocognitive deficits in schizophrenia? Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:321–330Link, Google Scholar

31. Breier A, Schreiber JL, Dyer J, Pickar D: National Institute of Mental Health longitudinal study of chronic schizophrenia. prognosis and predictors of outcome. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48:239–246Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Larsen TK, McGlashan TH, Moe LC: First-episode schizophrenia, I: early course parameters. Schizophr Bull 1996; 22:241–256Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar