A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study of Risperidone Maintenance Treatment in Children and Adolescents With Disruptive Behavior Disorders

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The authors compared the effects of maintenance versus withdrawal of risperidone treatment in children and adolescents with symptoms of disruptive behavior disorder. METHOD: Patients with disruptive behavior disorder (5–17 years of age and a range of intellect) who had responded to risperidone treatment over 12 weeks were randomly assigned to 6 months of double-blind treatment with either risperidone or placebo. The primary efficacy measure was time to symptom recurrence, defined as sustained deterioration on either the Clinical Global Impression severity rating (÷2 points) or the conduct problem subscale of the Nisonger Child Behavior Rating Form (÷7 points). Secondary efficacy measures included rates of discontinuation due to symptom recurrence, disruptive behavior disorder symptoms, and general function. Safety and tolerability were also assessed. Risperidone dosage was based on weight (patients <50 kg: 0.25–0.75 mg/day; patients ÷50 kg: 0.5–1.5 mg/day). RESULTS: Treatment was initiated in 527 patients, with 335 randomly assigned to a double-blind maintenance condition. Time to symptom recurrence was significantly longer in patients who continued risperidone treatment than in those switched to placebo. Symptom recurrence in 25% of patients occurred after 119 days with risperidone and 37 days with placebo. Secondary efficacy measures also favored risperidone over placebo. Weight increased over the initial 12 weeks of treatment (mean weight z score change=0.2, SD=2.7, N=511), after which it plateaued. CONCLUSIONS: This study is the first placebo-controlled maintenance versus withdrawal trial of its kind in disruptive behavior disorder and provides evidence that patients who respond to initial treatment with risperidone would benefit from continuous treatment over the longer term.

Disruptive behavioral disorders of childhood include conduct disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, and disruptive behavior disorder not otherwise specified. These disorders occur in 7.3%–11.1% of children and adolescents and represent a significant burden, with three-quarters of children diagnosed with conduct disorder or oppositional defiant disorder referred to psychiatric services in a 1-year sample (1, 2). In addition, both conduct disorder and oppositional defiant disorder are often comorbid with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), depression, and anxiety (3).

Disruptive behavior disorders often persist and significantly impact both childhood and adult life. A 7-year longitudinal study of children with conduct disorder showed recovery by mid-to-late adolescence in less than 15% (4). Treatment of disruptive behavior disorders is important because persistent symptoms are linked to difficulty in school, social development, and adult health (5). Long-term persistence and consequences from disruptive behavior disorder often necessitate chronic therapy, with a focus on maintenance of symptom control. However, no studies have been conducted on the duration of treatment necessary for children with disruptive behavior disorders. This withdrawal trial therefore assesses the longer-term need for pharmacological intervention in patients who have shown an initial response to risperidone.

Risperidone has consistently demonstrated efficacy and safety in both controlled short-term (6, 7) and open-label long-term (8–10) studies. The current study expands on the earlier long-term studies by including adolescents and individuals of normal intellect. Patients who had been successfully treated with risperidone to manage disruptive behavior disorder symptoms were randomly assigned to double-blind treatment with risperidone or placebo, and any recurrence of symptoms was closely monitored.

Method

This double-blind, international, multicenter study was conducted from August 2001 to September 2003 in 25 centers in eight countries (Belgium, Germany, Great Britain, Israel, Poland, South Africa, Spain, and the Netherlands). Before initiation of this study, local Independent Ethics Committees approved the protocol and written informed consent procedures. This study was conducted in accordance with good clinical practice and the Declaration of Helsinki, Finland.

Patients

Children and adolescents (ages 5–17 years) without moderate or severe intellectual impairment (IQ ≥55, as determined with assessments [11–13] given at screening or within the preceding 3 years) were eligible for enrollment if they met DSM-IV criteria for conduct disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, or disruptive behavior disorder not otherwise specified, with the diagnosis confirmed by the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children–Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL). The K-SADS-PL has been validated in children ages 7–17 years, with excellent reliability for diagnosing disruptive behavior disorders (14). Inclusion required that the conduct problem be serious enough to warrant clinical treatment with risperidone and be associated with a score ≥24 on the conduct problem subscale of the Nisonger Child Behavior Rating Form—parent version (15, 16) at both screening and treatment initiation. Children and adolescents with comorbid ADHD were not excluded, but those with other serious medical or psychiatric conditions such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder were excluded. Concomitant therapy with stable psychostimulant dosing was permitted (i.e., patients must have been receiving a stable dose of psychostimulants for at least 30 days before study entry and that dose must have been maintained by the clinician). Treatment with additional antipsychotics, lithium, anticonvulsants, or antidepressants was not permitted. Medications to treat extrapyramidal symptoms were allowed only after dose reduction was attempted but were generally discouraged. In addition, each patient was required to have a responsible caregiver to provide assessments and ensure medication compliance. After provision of a complete description of the study, written informed consent was obtained from the parents or guardians of each patient before study enrollment and assent was gained from every patient.

Study Design

Before treatment, all patients were evaluated with standardized and validated measures of disruptive behavior disorder symptoms and general function, which were translated and back-translated into the languages of the various trial centers. These were the Nisonger Child Behavior Rating Form (in particular, the conduct problem subscale, which includes items such as “explosive, easily angered,” “knowingly destroys property,” and “threatens people”), the Clinical Global Impression (CGI) severity scale (17), the Children’s Global Assessment Scale (18), and a visual analogue scale for rating the most troublesome symptom. In addition, at day 7 from the start of treatment and at subsequent assessments, CGI change ratings were obtained. Cognitive function was assessed with a continuous performance test (10) and a modified version (19) of the California Verbal Learning Test–Children’s Version (MVLT-10 for patients with chronological or mental age <6, MVLT-15 for those with chronological or mental age ≥6). All patients also underwent a physical examination (including assignment of Tanner stage), laboratory testing (hematology, chemistry, and urinalysis), and ECG.

Patients were treated with risperidone, 1 mg/ml oral solution, initially as a once-daily dose in the evening, but this could be divided into twice-daily dosing if indicated (e.g., if sedation or breakthrough symptoms occurred). Treatment was divided into three sequential phases: acute treatment (6 weeks of open-label risperidone), continuation treatment (6 weeks of single-blind risperidone), and maintenance (6 months of double-blind risperidone or placebo). The single-blind phase was employed to ensure that the patient and caregiver were unaware of the exact timing of the randomization to risperidone or placebo. Patients and caregivers were informed, before the onset of the trial, that the randomization would take place at some point during the second 6-week treatment period (continuation phase). During the acute treatment phase, patients were treated with flexible risperidone doses depending on their body weight. Patients with a body weight up to 50 kg started at 0.25 mg/day, and those with a body weight of 50 kg or more were treated initially with 0.50 mg/day. If deemed necessary by the treating physician, this dose was increased by 0.25 mg (for patients <50 kg) or 0.50 mg (those ≥50 kg) on the third and fifth day of treatment to a maximum daily dose of 0.75 mg (patients <50 kg) or 1.5 mg (those ≥50 kg). Response during acute treatment was defined as achieving either ≥50% reduction in score on the Nisonger Child Behavior Rating Form conduct problem subscale or a score ≤17 on the conduct problem subscale with a score of 1 or 2 (“much” or “very much” improved) on the CGI change scale. Responders from the acute treatment phase entered into the continuation treatment phase and remained at the dose level used in acute treatment. Dose changes to manage adverse events were allowed during this phase, but every clinically acceptable attempt had to be made to keep the dose constant. Sustained response was defined as having at week 12 no deterioration beyond 3 points on the Nisonger Child Behavior Rating Form conduct problem subscale compared with the end of the acute phase (week 6). Also required was a score <24 on the conduct problem subscale at weeks 8 and 10 and exhibited improvement compared with screening. Patients exhibiting sustained response during continuation treatment were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to one of two maintenance phase conditions: risperidone at the same dose used in the continuation phase or placebo. Maintenance therapy continued for up to 6 months. There was no down-titration of medication for those switched to placebo. The randomization code was generated by the study sponsor, with treatment numbers allocated at each investigative center in chronological order. Placebo and risperidone oral solutions were identical in appearance and flavor.

Outcome Assessments

The primary efficacy measure was time to symptom recurrence, defined during the double-blind maintenance phase as a deterioration of ≥2 points on the CGI severity scale or ≥7 points on the conduct problem subscale at two consecutive visits 6–8 days apart. The CGI severity scale was chosen as a measure for symptom recurrence rather than the CGI change scale because time has less of an impact on the CGI severity scale, given that the rater is not required to recall the condition at baseline. In addition, the CGI severity scale was considered to be less subject to variability introduced by potential changes in raters. As soon as patients met the criteria for symptom recurrence (the second confirmatory visit), they were discontinued from the trial. Secondary efficacy measures included rates of discontinuation due to symptom recurrence, and change from screening or baseline on the Nisonger Child Behavior Rating Form subscales, CGI severity and change scales, and visual analogue scale rating of the most troublesome symptom, all assessed biweekly during acute and continuation treatment and monthly during maintenance treatment. The Children’s Global Assessment Scale score was recorded at completion of the continuation and maintenance treatment phases.

Safety and tolerability were assessed by recording the occurrence of spontaneously reported adverse events. Treatment-emergent adverse events (i.e., new in onset or changed in severity) were tabulated separately for each phase of the study. Cognitive function, laboratory values, ECG, and vital signs were measured at screening and the completion of the continuation and maintenance treatment phases. A physical examination, including assignment of Tanner stage, was performed at screening and completion of maintenance treatment. Height and weight were measured at screening, on completion of acute and continuation treatment phases, and after 3 and 6 months of maintenance treatment. To place weight changes into the context of normal growth, results at each visit for height, weight, and body mass index were transformed to z scores using the SAS code available at http://www.cdc.gov/growthcharts. These z scores indicate the extent that a child’s weight, height, or body mass index differs from the average for children of the same age and sex, using a U.S. reference population.

Data Analysis

A power analysis identified that 208 patients needed to participate in maintenance therapy to achieve a 90% power for detecting a difference in time to symptom recurrence between treatment groups. Accounting for anticipated dropouts with no postbaseline data, 225 patients were required to begin maintenance therapy, necessitating at least 364 patients for acute treatment, since 65% of patients were expected to respond during the acute phase, and 95% of these were expected to fulfill the requirements for randomization.

Descriptive statistics were used to evaluate demographic and baseline data as well as change from screening and baseline for the total and subscale scores of the Nisonger Child Behavior Rating Form, visual analogue scale ratings of the most troublesome symptom, CGI change and severity ratings, and Children’s Global Assessment Scale score. Screening occurred in the 7 days before enrollment in acute therapy. Baseline was considered to be initiation of double-blind maintenance treatment. Efficacy analyses were evaluated for the intent-to-treat dataset, defined as all patients who received at least one dose of placebo or risperidone during the double-blind maintenance phase. A Cox proportional hazard model was used to compare time to symptom recurrence between treatment groups. The Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test for general association, with country controlled, was used for assessing symptom recurrence rate. All statistical tests were interpreted at the 5% significance level (two-tailed). Safety analyses were performed for all patients who received at least one dose of study drug. Prevalence of adverse events and change from screening and baseline in vital signs, laboratory tests, ECG, and cognitive tests were summarized with descriptive statistics. Changes from screening and baseline in height and weight (transformed into z scores) were also summarized by descriptive statistics.

Results

Patients

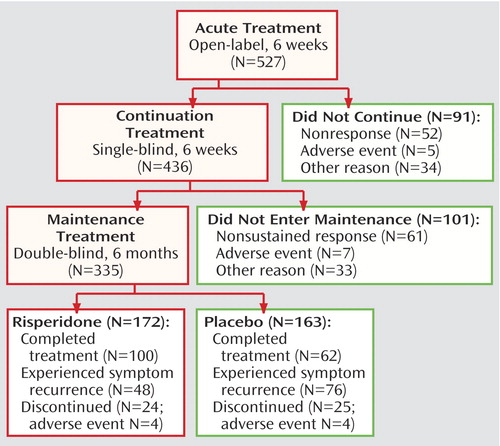

A total of 575 patients were screened and of these, 527 patients were enrolled in the 6-week, open-label, acute treatment phase. Overall, 436 patients continued single-blind treatment for an additional 6 weeks, and 335 were randomly assigned to 6 months of double-blind maintenance treatment (Figure 1). Patient demographics are shown in Table 1. The majority of patients were Caucasian (87%, N=459) and of normal (IQ>84) intellect (63%, N=333); a significant proportion (44%, N=231) were adolescents. Most (66%, N=349) had comorbid ADHD.

The average Nisonger Child Behavior Rating Form conduct problem subscale score of 35.2 (SD=6.29) at screening indicates that patients had severe symptoms. The symptom rated most often with the visual analogue scale as the most troublesome symptom was categorized as either aggression (46%) or oppositional defiant behavior (43%). Mean Children’s Global Assessment Scale score at screening was 47.0 (SD=9.9), corresponding to a moderate interference in most social areas or severe impairment in one area.

Treatment was discontinued before entering the double-blind maintenance phase by 192 (36%) patients, with most discontinuations due to patients not meeting the criteria for either initial response (10%, N=52) or sustained response (12%, N=61). Other reasons for discontinuation during the acute and continuation phases were adverse events (N=12), patient lost to follow-up (N=20), patient withdrawal of consent (N=15), patient noncompliance (N=14), patient ineligibility for study continuation (N=4), and other reasons (N=14). Double-blind maintenance treatment was completed by 162 of the patients who started this phase (48%), with most discontinuations due to meeting symptom recurrence criteria. Mean risperidone dosage was approximately 0.02 mg/kg per day (Table 2). Prior therapy was used by 351 (67%) of patients enrolled into the acute treatment phase, most commonly psychostimulants (39%), antipsychotics (26%), and anticonvulsants (7%). During acute and continuation treatment phases, 59% of all patients received concomitant medications (24% psychostimulants, 16% analgesics). During the maintenance phase, concomitant medications were taken by 55% of risperidone-treated patients (21% psychostimulants, analgesics 15%) and 50% of placebo-treated patients (22% psychostimulants, 12% analgesics).

Primary Efficacy

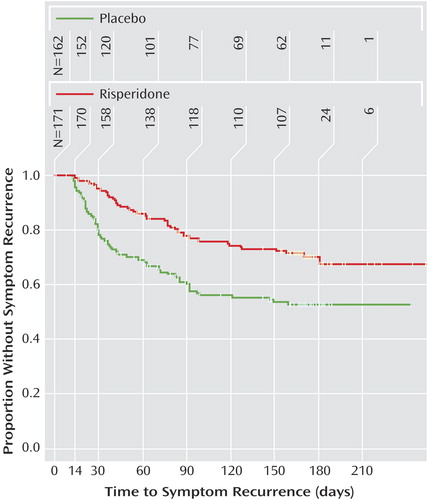

At the end of the maintenance phase, there was a significant difference in rate of symptom recurrence, based on efficacy scales and investigator impression, between those assigned to risperidone (27.3%, N=47) and those assigned to placebo (42.3%, N=69) (c2=10.04, df=1, p=0.002). Time to symptom recurrence was significantly shorter with placebo compared with maintenance risperidone (c2=18.45, df=1, p<0.001) (Figure 2). Symptom recurrence occurred in 25% of patients after 119 days with risperidone and 37 days with placebo. Six-month Kaplan-Meier symptom recurrence estimates were 29.7% for risperidone and 47.1% for placebo. The instantaneous risk-to-symptom recurrence (hazard ratio) was 2.24 (95% CI=1.54–3.28) times higher after switching to placebo compared with continuing risperidone. Since less than 50% of patients met the criteria for symptom recurrence, the median time to symptom recurrence was not estimable. For patients who discontinued due to symptom recurrence, the range of time to symptom recurrence was 12–159 days among those receiving placebo and 14–181 days for those receiving risperidone. Risk for symptom recurrence was not affected by age, gender, diagnosis, or baseline disruptive behavior disorder severity.

Secondary Efficacy

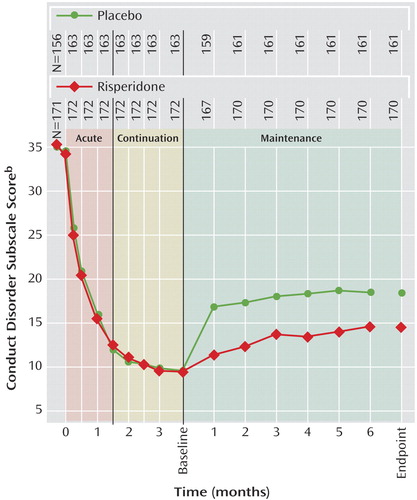

Risperidone was associated with a significantly lower rate of symptom recurrence than placebo (27.3% versus 42.3%) (c2=10.04, df=1, p=0.002). In the intent-to-treat population, conduct problem scores decreased (i.e., condition improved) significantly within 2 weeks of treatment initiation and continued to improve further throughout acute and continuation treatment (Figure 3). During the maintenance phase, mean scores increased compared with the start of the maintenance phase in both groups, but deterioration at endpoint of the maintenance phase was significantly higher in the placebo group (F=13.17, df=1,321, p<0.001). Change from the beginning of the maintenance phase to endpoint for all Nisonger Child Behavior Rating Form subscales, the most troublesome symptom visual analogue scale rating, and the global measurements (CGI severity and Children’s Global Assessment Scale) favored risperidone, with significant differences (p≤0.01) between risperidone and placebo on all measures except the insecure/anxious, self-injury/stereotypic behavior, self-isolated/ritualistic, and overly sensitive subscales of the Nisonger Child Behavior Rating Form. The changes in secondary efficacy measures in the intent-to-treat population from screening to the end of the continuation phase and from the beginning of the maintenance phase until endpoint are presented in Table 3.

Patients maintained on risperidone for up to 9 months had significant improvements (by two decile categories) in mean Children’s Global Assessment Scale scores, corresponding to a change from moderate or severe impairment to generally functioning well.

Safety and Tolerability

Safety data were available for all 527 patients enrolled in the acute treatment phase. Treatment-emergent adverse events were reported more frequently during acute treatment (54.8%) compared with the continuation phase (34.9%) and maintenance phase (47.7% with risperidone versus 36.2% with placebo) (Table 4). The most frequently reported treatment-emergent adverse events were headache, somnolence, fatigue, and increased appetite. Most treatment-emergent adverse events were mild or moderate in severity. Treatment-emergent adverse events resulted in treatment discontinuation in 1.7% of patients during acute treatment, 2.1% during the continuation phase, and 1.7% with risperidone and 0.6% with placebo during the maintenance phase. Treatment-emergent adverse events that resulted in treatment discontinuation during the maintenance phase with risperidone were involuntary muscle contractions, abnormal ECG, and paranoid reaction, each of which occurred in one patient. One patient receiving placebo discontinued because of an implantation complication related to treatment for a different condition. The incidence of extrapyramidal symptoms was low (Table 5), and antiextrapyramidal-symptom medications were used to treat extrapyramidal symptoms in only two patients. There were no reports of tardive dyskinesia. Potentially prolactin-related treatment-emergent adverse events were infrequent and occurred during acute and continuation therapy in 10 patients (six male [gynecomastia] and four female [amenorrhea in one, breast pain and lactation in one, and lactation only in two]) and during risperidone maintenance in three male subjects (gynecomastia) and two female subjects (amenorrhea and lactation in one, and breast discharge in one). There were no potentially prolactin-related treatment-emergent adverse events among those receiving placebo during the maintenance phase. Somnolence was most commonly reported during the acute phase of treatment (11.6%) and dramatically decreased thereafter. In general, somnolence was of mild-to-moderate severity and time-limited to treatment initiation or dose increase.

There was no clinically significant change in mean fasting glucose levels during treatment. Neither were there clinically meaningful changes in other laboratory values with the exception of prolactin plasma levels. Mean prolactin plasma levels increased during acute and continuation phases from 8.3 ng/ml (SD=6.6) at screening to 27.2 ng/ml (SD=20.1) at the end of the continuation phase. In the intent-to-treat population, mean levels decreased during the maintenance phase both for patients treated with risperidone (baseline: 29.4 ng/ml [SD=21.9]; endpoint: 20.3 ng/ml [SD=21.3]) and those receiving placebo (baseline: 29.7 ng/ml [SD=18.0]; endpoint: 9.6 ng/ml [SD=9.5]).

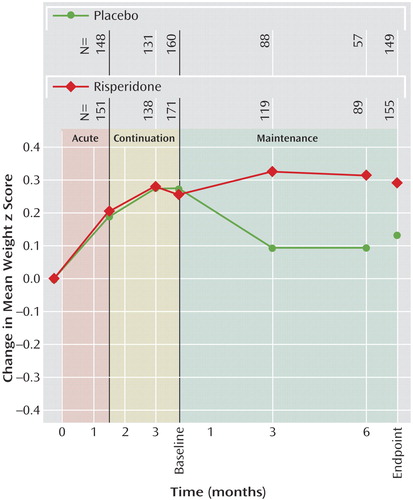

Mean weight increased from screening to the end of the continuation phase (week 12) by 3.2 kg (SD=2.49). Subsequently, from the beginning to the end of the maintenance phase, mean weight increased by 2.1 kg (SD=2.7) for risperidone-treated patients, whereas patients receiving placebo experienced a decrease in mean weight of –0.2 kg (SD=2.2). Mean height and body mass index increased over the first 12 weeks of treatment by 1.7 cm (SD=2.1) and 1.0 kg/m2 (SD=1.1), respectively. From the beginning to the end of the maintenance phase, height increased in both groups (risperidone: mean=2.5 cm, SD=1.9; placebo: mean=1.5 cm, SD=1.7), and body mass index increased in risperidone-treated patients (0.3 kg/m2 [SD=1.1]) but decreased for patients switched to placebo (–0.4 kg/m2 [SD=0.9]). Among patients receiving risperidone in all study phases, mean weight and body mass index z scores increased during the first 12 weeks of treatment (weight: mean change=0.3 [SD=0.3]; body mass index: mean change=0.3 [SD=0.4]). During maintenance treatment no further weight gain beyond natural growth was observed (change in weight z scores from maintenance baseline: mean=0.0, SD=0.3, at endpoint and mean=0.1, SD=0.3, at other time points). In placebo patients, mean weight z scores decreased compared with maintenance baseline by 0.1 (SD=0.2). Mean body mass index z scores showed a similar pattern, with no increase in risperidone patients (mean change from baseline to endpoint=0.0, SD=0.4) and a decrease in placebo patients (mean change=–0.2, SD=0.3). Figure 4 indicates that weight increase was an initial effect, was not continued with prolonged treatment, and was reversed with discontinuation of risperidone treatment.

There were no clinically significant changes in vital signs and no significant changes in QT intervals during any treatment phases. Most mean changes in ECG parameters were small, and the incidences of high heart rate (>100 bpm) and low PR interval (≤120 msec) during the double-blind maintenance phase were similar between the risperidone and placebo groups.

Changes in cognitive testing scores from beginning to end of the double-blind maintenance phase were small and similar for the risperidone and placebo groups. Mean changes on the MVLT-15 (total correct scores) were 0.1 (SD=1.7) for placebo (N=139) and –0.3 (SD=3.8) for risperidone (N=138); on the MVLT-10 these were 4.3 (SD=4.9) for placebo (N=5) and 2.0 (SD=2.1) for risperidone (N=9). The scores on the continuous performance test were also similar between placebo- and risperidone-treated patients (mean change in number of correct hits: placebo, mean=0.1 [SD=0.4], N=136; risperidone, mean=0.1 [SD=0.4], N=139). These differences were not statistically significant.

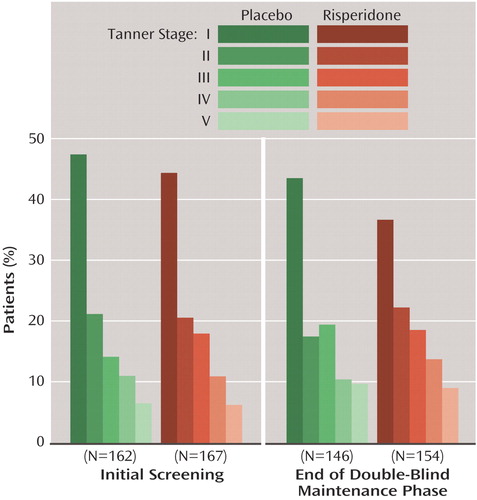

As expected, Tanner stages increased during the study, with similar changes in patients receiving risperidone and placebo during the maintenance phase (Figure 5).

Conclusions

Numerous studies support the clinical use of risperidone for the acute treatment of conduct disorder and other disruptive behavior disorders in patients with subaverage IQ (6–10). This study evaluated the efficacy of long-term maintenance treatment in a broader population and included children and adolescents with average IQ. Risperidone, at low doses of 0.02 mg/kg per day, had a beneficial acute and sustained effect on disruptive behavior disorder and was significantly better than placebo at maintaining symptom control. Before the current study, there were no controlled data to support the benefits of long-term pharmacological therapy for disruptive behavior disorders. Data from the current study suggest that some individuals benefit from risperidone treatment beyond initial symptom improvement and stabilization. Analysis of the time to symptom recurrence in the placebo group suggests that exacerbation of acute behavioral symptoms in these disruptive behavior disorders occurs rapidly, within 1–2 months of treatment discontinuation. Conversely, a subgroup of placebo-treated patients appears to have maintained stabilization following 12 weeks of acute treatment with risperidone.

A limitation of this trial is the criteria used to identify “symptom recurrence,” which may be considered too conservative. In standard practice, a patient meeting these criteria would typically receive a dose adjustment or a change in intervention. A second limitation of our study is that only patients who responded to initial treatment were randomized, potentially introducing a selection bias. This was, in part, addressed by including a single-blind period prior to double-blind randomization, but it is likely that this did not fully remove any dropout bias due to the perceived placebo condition. However, most patients did respond to initial risperidone treatment, suggesting that these findings can be generalized. A substantial proportion of patients (24%) were treated with concomitant psychostimulants, and the effect of these on outcome was not assessed. However, any effects should have been minimized, since psychostimulant dose had been stabilized for 30 days before entry into the trial and every attempt was made to keep dose constant throughout the trial. Previous studies have also indicated that the presence or absence of psychostimulants does not affect the efficacy or tolerability of risperidone (20).

The primary goal of managing disruptive behavior disorder symptoms in pediatric patients is to enhance function within the family, peer group, and school. The current study demonstrates persistent benefits for up to 6 months in patients whose previous response to risperidone occurred across a broad range of symptoms, including enhanced prosocial behaviors. Cognition, including the critical areas of verbal learning and memory and attention, did not deteriorate with risperidone treatment. Risperidone thus improves symptoms of disruptive behavior disorder and conduct disorder while preserving intellectual functioning, an important finding since roughly two-thirds of the study population had comorbid ADHD.

The safety data collected in this study reflect the larger body of our published data in over 1,300 children and adolescents with disruptive behavior disorder treated with risperidone (6–10). Overall, risperidone was well tolerated, with infrequent symptoms of movement disorders and no cases of tardive dyskinesia. Weight gain in excess of that expected in a growing population occurred predominantly during the first 12 weeks of risperidone treatment, and thereafter matched expected weight gain associated with continued growth and development, as suggested by no change from beginning to end of the maintenance phase in mean weight z scores in patients treated with risperidone. Sexual maturation and growth were not impaired with extended risperidone treatment. Risperidone treatment was associated with increased mean prolactin plasma levels—especially at treatment initiation—but clinical symptoms potentially related to high prolactin plasma levels were uncommon and were unrelated to dose or prolactin level. This is consistent with previously published long-term data showing an initial increase in prolactin levels that decreased toward normal levels with continued treatment (21). Given these findings, clinicians are specifically encouraged to monitor for the occurrence of sexual side effects rather than changes in prolactin levels. Somnolence occurred most commonly during the acute treatment phase (11.6%) and improved with continued risperidone treatment.

In conclusion, this study is the first placebo-controlled, long-term maintenance trial of its kind in disruptive behavior disorder and provides strong evidence that patients who respond to 12 weeks of initial treatment with risperidone continue to benefit for up to an additional 6 months. Low-dose risperidone improves a broad range of behavioral and social symptoms in children and adolescents with disruptive behavior disorders, including those with normal IQ. These benefits are maintained in the long term, with substantial worsening of symptoms more likely to occur in patients who do not continue maintenance risperidone treatment.

|

|

|

|

|

Presented in part at the 16th congress of the International Association for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Allied Professions, Berlin, Aug. 22–26, 2004; the 17th congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology, Stockholm, Oct. 9–13, 2004; and the 43rd annual meeting of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology, San Juan, Puerto Rico, Dec. 12–16, 2004. Received March 10, 2005; revisions received June 16 and Oct. 20, 2005; accepted Nov. 7, 2005. From the Tel-Aviv-Brull Community Mental Health Center, Child and Adolescent Outpatient Clinic, Tel Aviv, Israel. Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. Reyes, Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development, 1125 Trenton-Harbourton Rd., Titusville, NJ 08530; [email protected] (e-mail).The authors thank Dawn Marcus, M.D., and Claire McNulty, Ph.D., for help with the preparation of the manuscript.This study was supported by Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research and Development.

Figure 1. Study Progression of Children and Adolescents With Disruptive Behavior Disordersa

aSymptom recurrence was defined as a deterioration from baseline of ≥2 points on the CGI severity scale or ≥7 points on the Nisonger Child Behavior Rating Form conduct problem subscale at two consecutive visits 6–8 days apart. For seven placebo group patients and one risperidone-treated patient, symptom recurrence was not verified at a second visit. These patients were considered as censored in the primary efficacy analysis.

Figure 2. Time to Symptom Recurrence Among Children and Adolescents With Disruptive Behavior Disorders Randomly Assigned to 6 Months of Double-Blind Maintenance Treatment With Risperidone or Placebo Following Acute Response to Risperidonea

aTwo patients (one from each group) had no postbaseline efficacy data and were censored at day 0. Time to symptom recurrence was significantly shorter with patients who switched to placebo compared with those maintaining risperidone (p<lst<0.001).

Figure 3. Conduct Problem Scores During Different Treatment Phasesa for Children and Adolescents With Disruptive Behavior Disorders Participating in a Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study of Risperidone Maintenance Treatment

aAcute phase was 6 weeks of open-label risperidone treatment. The continuation phase was 6 weeks of single-blind treatment for those responding to acute phase treatment, after which those patients exhibiting sustained response entered the maintenance phase in which they were randomly assigned in a double-blind manner to receive risperidone or placebo for up to 6 months.

bFrom the Nisonger Child Behavior Rating Form—Parent Version. Data points are mean scores with last observation carried forward. Lower scores indicate improvement.

Figure 4. Mean Weight Change (z scores) in Children and Adolescents With Disruptive Behavior Disorders Randomly Assigned to 6 Months of Double-Blind Maintenance Treatment With Risperidone or Placebo Following Acute Response to Risperidone

Figure 5. Tanner Stages at Initial Screening and Endpoint of Children and Adolescents With Disruptive Behavior Disorders Randomly Assigned to 6 Months of Double-Blind Maintenance Treatment With Risperidone or Placebo Following Acute Response to Risperidone

1. Canino G, Shrout PE, Rubio-Stipec M, Bird HR, Bravo M, Ramirez R, Chavez L, Alegria M, Bauermeister JJ, Hohmann A, Ribera J, Garcia P, Martinez-Taboas A: The DSM-IV rates of child and adolescent disorders in Puerto Rico: prevalence, correlates, service use, and the effects of impairment. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2004; 61:85–93Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Arcelus J, Vostanis P: Child psychiatric disorders among primary mental health service attenders. Br J Gen Pract 2003; 53:214–216Medline, Google Scholar

3. Maughan B, Rowe R, Messer J, Goodman R, Meltzer H: Conduct disorder and oppositional defiant disorder in a national sample: developmental epidemiology. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2004; 45:609–621Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Lahey BB, Loeber R, Burke J, Rathouz PJ: Adolescent outcomes of childhood conduct disorder among clinic-referred boys: predictors of improvement. J Abnorm Child Psychol 2002; 30:333–348Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Burke JD, Loeber R, Birmaher B: Oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder: a review of the past 10 years, part II. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2002; 41:1275–1293Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Aman MG, De Smedt G, Derivan A, Lyons B, Findling RL (Risperidone Disruptive Behavior Study Group): Double-blind, placebo-controlled study of risperidone for the treatment of disruptive behaviors in children with subaverage intelligence. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159:1337–1346Link, Google Scholar

7. Snyder R, Turgay A, Aman M, Binder C, Fisman S, Carroll A: Risperidone conduct study group: effects of risperidone on conduct and disruptive behavior disorders in children with subaverage IQs. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2002; 41:1026–1036Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Turgay A, Binder C, Snyder R, Fisman S: Long-term safety and efficacy of risperidone for the treatment of disruptive behavior disorders in children with subaverage IQs. Pediatrics 2002; 110:e34Google Scholar

9. Findling RL, Aman MG, Eerdekens M, Derivan A, Lyons B (Risperidone Disruptive Behavior Study Group): Long-term, open-label study of risperidone in children with severe disruptive behaviors and below-average IQ. Am J Psychiatry 2004; 161:677–684Link, Google Scholar

10. Croonenberghs J: Risperidone in children with disruptive behavior disorders: a 1-year, open-label study of 504 patients. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2005; 44:64–72Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Wechsler D: Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence, Revised. New York, Psychological Corporation/Harcourt, Brace, 1983Google Scholar

12. Wechsler D: Manual for the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, 3rd ed. San Antonio, Tex, Psychological Corp, 1991Google Scholar

13. Thorndike RL, Hagen EP, Sattler JM: Guide for Administering and Scoring the Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scale, 4th ed. Chicago, Riverside Publishing, 1986Google Scholar

14. Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U, Flynn C, Moreci P, Williamson D, Ryan N: Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children—Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997; 36:980–988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Aman MG, Tassé MJ, Rojahn J, Hammer D: The Nisonger CBRF: a child behavior rating form for children with developmental disabilities. Res Dev Disabil 1996; 17:41–57Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Tassé MJ, Aman MG, Rojahn J: The Nisonger Child Behavior Rating Form: age and gender effects and norms. Res Dev Disabil 1996; 17:59–75Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Guy W (ed): ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology: Publication ADM 76-338. Washington, DC, US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, 1976, pp 218-222Google Scholar

18. Shaffer D, Gould MS, Brasic J, Ambrosini P, Fisher P, Bird H, Aluwahlia S: A Children’s Global Assessment Scale (CGAS). Arch Gen Psychiatry 1983; 40:1228–1231Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Delis DC, Kramer JH, Kaplan E, Ober BA: The California Verbal Learning Test Manual. New York, Psychological Corp, 1987Google Scholar

20. Aman MG, Binder C, Turgay A: Risperidone effects in the presence/absence of psychostimulant medicine in children with ADHD, other disruptive behavior disorders, and subaverage IQ. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2004; 14:243–254Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Findling RL, Kusumakar V, Daneman D, Moshang T, De Smedt G, Binder C: Prolactin levels during long-term risperidone treatment in children and adolescents. J Clin Psychiatry 2003; 64:1362–1369Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar