Psychotherapy in the Journal: What’s Missing?

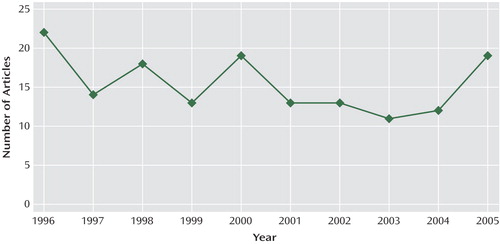

The American Journal of Psychiatry has published a small but consistent stream of articles about psychotherapy over the past decade (Figure 1). Recent Journal articles on psychotherapy have ranged from an assessment of psychotherapy in clinical trials (1) to an analysis of suicides as failures in therapeutic outcomes (2). Case Conferences and the new Treatment in Psychiatry series both examine techniques and outcomes of psychotherapeutic treatment (3, 4). Psychiatric journals have responded to calls from inside and outside our profession to publish rigorous controlled studies of psychotherapy’s efficacy (5, 6). Despite these efforts, readers continue to request more clinically relevant articles about psychotherapy.

Randomized, controlled trials of psychotherapy have been particularly problematic. Because of the requirements for manualization and standardization, the treatments delivered in psychotherapy studies often do not reflect clinical practice. The cost and pragmatics of conducting long-term psychotherapy studies make most treatment trials unrepresentatively brief. Although the results of treatments of several weeks’ duration can be positive, these treatments do not seek to achieve stable changes that are often the goal of psychotherapy in actual clinical practice. Furthermore, studies are almost always disorder based, even though many patients wish to discuss problems of living that stem from personality characteristics that are intermingled with a specific disorder.

The recent emphasis on more naturalistic effectiveness trials may be particularly applicable to the assessment of psychotherapies. Although efficacy trials emphasize scientifically rigorous methods, including placebo control, to document the effect of a treatment, effectiveness trials forgo some aspects of the scientific method to determine if treatments are effective in the clinical setting in which they are usually performed. These studies use pre- and posttreatment ratings of individual patients to compare different treatments across groups. Differences in psychotherapeutic techniques, interactions with pharmacotherapies, and intrinsic therapist and patient variables can all be considered. These trials can monitor the quality of psychotherapies in terms of adherence to specific aspects of technique just as adherence to specific drug regimens is monitored. This type of research can thus elucidate which therapeutic interventions are most helpful to which patient. For analyses to be successful, large groups at many sites must be studied. Psychotherapy is offered as a treatment modality in several of the ongoing effectiveness trials of the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), whose reports appear regularly in the Journal. We welcome more such trials to these pages.

Psychiatrists, like most physicians, generally endorse the need for efficacy and effectiveness trials to guide their practice, but they also report that they find these articles difficult to read and somehow lacking in immediate appeal. When an article is about psychotherapy, the frustration is particularly acute. An initiative to address this problem has begun among more biologically oriented psychiatric researchers. Stephen Marder, director of NIMH’s TURNS and MATRICS consortia to test new pharmacotherapeutics for schizophrenia, has pointed out that patients’ impressions of the effect of a new drug are often more illuminating than a change in rating scales. Patients can describe how the drug affected their thinking and mood more exquisitely than their answers to questions on research instruments can. Marder recommends that reports of drug therapies include direct accounts from patients of their experience with the treatment. Thomas Laughren of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) made a similar point. He stated that the FDA will not approve new drugs for cognitive deficits in schizophrenia based on neuropsychological testing alone. In addition, there must be evidence from the patients and their families that their thinking has changed (7). These directions recall Leon Eisenberg’s prediction that when the ultimate neurobiological treatment for schizophrenia is someday devised and everyone is marveling over the results on the computer monitor, there may be only one psychiatrist left who will remember to ask the patient, “How do you feel?”

Anecdotes and testimonials may seem anathema to the scientific rigor that is needed to establish psychiatric treatment and psychotherapy in particular as an evidence-based practice. We do not propose that any of the methodology of efficacy and effectiveness be compromised. However, wherever appropriate, paragraphs or tables that use the patients’ own words to report what has happened are a desirable feature that contributes to the validity of the report, regardless of the treatment modality under study.

Generations of physicians have become psychiatrists because psychiatry above all other fields prizes listening to patients. Diagnostic assessment and psychotherapy are the classical vehicles of that experience. Now, the manualization of psychotherapy has followed the codification of diagnosis. Both innovations have enhanced our clinical abilities, but both have produced a literature that often seems to be lacking something. What is missing is what we initially sought in our professional lives—our patients’ voices.

Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. Gabbard, Baylor College of Medicine, One Baylor Plaza, Houston, TX 77030; [email protected] (e-mail).

Figure 1. The Number of Articles on Psychotherapy Published in the American Journal of Psychiatry by Year

1. McIntosh VVW, Jordan J, Carter FA, Luty SE, McKenzie JM, Bulik CM, Frampton CMA, Joyce PR: Three psychotherapies for anorexia nervosa: a randomized, controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry 2005; 162:741–747Link, Google Scholar

2. Hendin H, Haas AP, Maltsberger JT, Koestner B, Szanto K: Problems in psychotherapy with suicidal patients. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163:67–72Link, Google Scholar

3. Cutler JL, Goldyne A, Markowitz JC, Devlin MJ, Glick RA: Comparing cognitive behavior therapy, interpersonal psychotherapy, and psychodynamic psychotherapy (clin case conf). Am J Psychiatry 2004; 161:1567–1573Link, Google Scholar

4. Oldham JM: Borderline personality disorder and suicidality. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163:20–26Link, Google Scholar

5. Gabbard GO, Gunderson JG, Fonagy P: The place of psychoanalytic treatments within psychiatry. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2002; 59:505–510Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Institute of Medicine: Research Training in Psychiatry. Washington, DC, National Academy Press, 2003Google Scholar

7. Buchanan RW, Davis M, Goff D, Green MF, Keefe RS, Leon AC, Nuechterlein KH, Laughren T, Levin R, Stover E, Fenton W, Marder SR: A summary of the FDA-NIMH-MATRICS workshop on clinical trial design for neurocognitive drugs for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 2005; 31:5–19Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar