Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Investigation of Amantadine for Weight Loss in Subjects Who Gained Weight With Olanzapine

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study sought to determine if amantadine affects weight gain in psychiatric patients taking olanzapine. METHOD: Twenty-one adults who had gained at least 5 lb with olanzapine were randomly assigned to receive amantadine (N=12) or placebo (N=9) in addition to olanzapine. The length of time taking olanzapine ranged from 1 to 44 months. Body mass index, psychiatric status, and fasting blood levels were assessed at baseline and 12 weeks. RESULTS: Significantly fewer subjects taking amantadine gained weight, with a mean change in body mass index of –0.07 kg/m2 for the amantadine group and 1.24 kg/m2 for the placebo group. This effect remained significant when the authors controlled for baseline body mass index and length of olanzapine treatment. No changes in fasting glucose, insulin, leptin, prolactin, and lipid levels were seen. Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale scores remained stable. CONCLUSIONS: Amantadine induced weight stabilization in subjects taking olanzapine and was well tolerated.

Weight gain is the single most important tolerability issue for second-generation antipsychotics. Patients taking olanzapine gain an average of 4.15 kg (1) in 10 weeks, and 40.5% gain more than 7% of their baseline weight (2). Attempts to combat antipsychotic-induced weight gain are uncommon and have yielded mixed results. Human (3–5) and rodent (6) studies using amantadine to stabilize antipsychotic-induced weight gain have had promising results. Amantadine is a dopamine agonist that is approved for the treatment of extrapyramidal side effects of medications, idiopathic parkinsonism, and influenza A virus. The mechanism by which it stabilizes weight is unknown, but it is postulated to be related to its ability to decrease prolactin and thereby influence gonadal and adrenal steroids (7) or to decrease appetite through its dopaminergic anorexic effects (8). In contrast, olanzapine blocks dopamine stimulation at the dopamine D2 receptor (9).

Here we report the effects of a 12-week double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of amantadine on body mass index and glucose and lipid profiles in olanzapine-treated adults.

Method

Psychiatrically stable adult subjects were recruited from the Schizophrenia Treatment and Evaluation Program of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, private outpatient clinics, and the Dorothea Dix Clinical Research Unit in Raleigh, N.C., between January 2001 and June 2003. The subjects had gained at least 5 lb while taking olanzapine and were continuing to take it. Weight gained while they were taking olanzapine was determined by subject interview and verified by a review of medical records. Written informed consent was obtained from the subjects after the procedures had been fully explained. This study was approved by the institutional review board of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Medicine.

The subjects’ DSM-IV psychiatric diagnoses were determined by interview and chart review, and current symptoms were assessed with the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (10). Fasting laboratory studies were performed at study entry. The subjects were randomly assigned to receive amantadine (up to 300 mg/day) or placebo in a double-blind fashion and were offered 12 sessions of a healthy lifestyle education program and a 3-month membership to a gym or a commercial weight-loss program. Weight was measured monthly on the same digital scale, with shoes off and one layer of clothing on. Weight, fasting blood work, and Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale assessments were repeated at the end of the study.

Fasting glucose, insulin, prolactin, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and triglyceride levels were determined by standard laboratory methods. Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol was determined by the Friedewald calculation (total cholesterol – [high-density lipoprotein cholesterol + triglyceride/5]). Leptin levels were measured with the Linco human ultrasensitive radioimmunoassay kit (Linco Research Inc., St. Charles, Mo.).

The primary analysis compared body mass index changes over the study period in the amantadine and placebo groups. The intent-to-treat group (N=21) was used in the analysis with the last observation carried forward for missing data because of early withdrawals (N=3). Additional descriptive statistics were obtained for demographic and clinical information. The baseline equality of the two groups was evaluated by using t tests for continuous variables and Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables. A linear regression model evaluated significant predictors of changes in body mass index, including age, gender, race (Caucasian versus non-Caucasian), baseline body mass index, days of treatment, and type of therapy. The final model was identified with backward selection by eliminating covariates with p>0.05.

Results

Twenty-one subjects with schizophrenia (N=12), schizoaffective disorder (N=6), and bipolar disorder (N=3) were randomly assigned to take amantadine (N=12) or placebo (N=9). There were 16 Caucasians and nine women. The length of treatment with olanzapine before study entry ranged from 1 to 44 months (median=7 months). The subjects had gained 5 to 58 lb while taking olanzapine, and all had body mass indexes greater than 25 kg/m2. Baseline body mass indexes were similar, mean=32.9 kg/m2 (SD=5.0) and mean=31.8 kg/m2 (SD=7.5) for the amantadine and placebo groups, respectively, as were baseline waist-to-hip ratios and fasting glucose, cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, triglycerides, leptin, and prolactin levels. In addition to olanzapine (5 to 30 mg/day), 12 subjects were administered an antidepressant, eight a mood stabilizer, and four both, with no significant group differences (p=0.20 for mood stabilizers and p=1.00 for antidepressants, Fisher’s exact test). The subjects attended at least three lifestyle education sessions. Thirteen attended a gym or a commercial weight-loss program at least once: six subjects taking amantadine and seven taking placebo. Three early terminations occurred, all from the amantadine group. One was at 4.5 weeks because of a worsening of psychosis, one at 9 weeks because of an antipsychotic switch, and one at 9.3 weeks because of nonadherence to olanzapine.

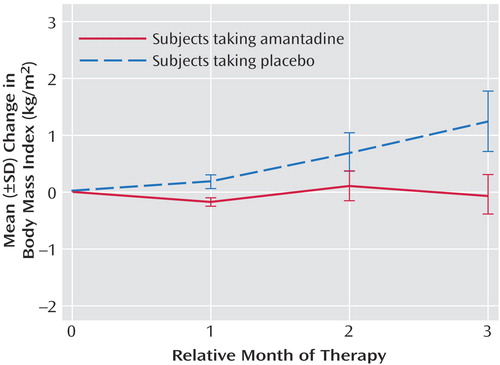

During the study, the amantadine group lost a mean of 0.8 lb (SD=7.8) and reduced its body mass index by a mean of 0.07 kg/m2 (SD=1.21). The placebo group gained a mean of 8.7 lb (SD=11.7) and increased its body mass index by a mean of 1.24 kg/m2 (SD=1.59). Body mass indexes continued to increase over the 12-week period in the placebo group (Figure 1). Significantly fewer subjects taking amantadine gained weight (p=0.05, Fisher’s exact test), with a mean decrease in body mass index of –0.07 kg/m2 (SD=1.21) for the amantadine group and a mean increase of 1.24 kg/m2 (SD=1.59) for the placebo group. This effect remained significant (t=–2.16, df=17, p<0.05) after we controlled for baseline body mass index and length of olanzapine treatment before study entry. Weight stabilization or loss occurred in eight (67%) of 12 amantadine-treated subjects and two (22%) of nine placebo subjects (p=0.05, Fisher’s exact test). The four amantadine subjects who gained weight were not different from the others in the group in terms of age, gender, initial body mass index, or length of time or dose of amantadine.

There were no significant differences in laboratory values between groups at the end of the study or within groups from the beginning to the end of the study. Mean fasting values for insulin, cholesterol, triglycerides, low-density lipoprotein, and prolactin were above the normal range in both groups at baseline and at the end of study. Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale total scores did not worsen during the study for either group.

Discussion

Our study had several limitations, including a small group size, a short length of study, and the use of antidepressants and mood stabilizers by the subjects. Despite these limitations, we found that amantadine halted ongoing weight gain in some adults with olanzapine-induced weight gain. This effect occurred early and reached a plateau by 8 weeks. Amantadine’s effect remained after we controlled for baseline body mass index and length of time the subjects had been taking olanzapine before study entry. This suggests that amantadine has beneficial effects on weight stabilization, even after subjects have gained substantial weight following months of olanzapine treatment.

Weight gain is commonly associated with lipid and carbohydrate disturbances. Here we found that despite weight stabilization, 12 weeks of amantadine did not improve fasting insulin or lipid levels. It is possible that longer treatment may show a metabolic effect. Both groups had mildly elevated prolactin levels at baseline, and a similar small decrease in this level had occurred in both groups by the final visit. This suggests that lowering prolactin is not the mechanism by which amantadine impedes weight gain.

Because of its dopaminergic properties, psychosis may be a possible but uncommon side effect of amantadine. In this study, there was no evidence of an adverse effect on psychosis because Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale scores did not worsen. However, since three early terminations in this study were in the amantadine group, it is not possible to exclude the side effect of worsening psychosis in this group.

Most obese individuals experience modest weight loss, roughly 5 to 20 lb, with diet, behavior therapy, or pharmacotherapy (11). Thus, it is unlikely that interventions initiated after substantial weight has been gained will have a great impact. Prevention of antipsychotic-related obesity is a critical goal, and investigation of the use of amantadine started concurrently with antipsychotic medication is imperative.

Presented at the 12th Biennial Winter Workshop on Schizophrenia, Davos, Switzerland, Feb. 7–13, 2004. Received May 25, 2004; revision received Aug. 17, 2004; accepted Sept. 13, 2004. From the Department of Psychiatry and the Department of Nutrition, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. Graham, Department of Psychiatry, CB 7160, UNC Neurosciences Hospital, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-7160; karen_[email protected] (e-mail). Supported in part by grants from the NIH (National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases) to the University of North Carolina Clinical Nutrition Research Center (DK-56350) and the General Clinical Research Centers program of the Division of Research Resources (RR-00046) and by an unrestricted gift from Eli Lilly and Company.

Figure 1. Monthly Mean Change in Body Mass Index From Baseline in Subjects Taking Amantadine or Placebo With Olanzapinea

aLast-observation-carried-forward analysis.

1. Allison DB, Mentore JL, Heo M, Chandler LP, Cappelleri JC, Infante MC, Weiden PJ: Antipsychotic-induced weight gain: a comprehensive research synthesis. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:1686–1696Abstract, Google Scholar

2. Beasley CM Jr, Tollefson GD, Tran PV: Safety of olanzapine. J Clin Psychiatry 1997; 58(suppl 10):13–17Google Scholar

3. Gracious BL, Krysiak TE, Youngstrom EA: Amantadine treatment of psychotropic-induced weight gain in children and adolescents: case series. J Child Adolescent Psychopharmacol 2002; 12:249–257Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Floris M, Lejeune J, Deberdt W: Effect of amantadine on weight gain during olanzapine treatment. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2001; 11:181–182Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Correa N, Opler LA, Kay SR, Birmaher B: Amantadine in the treatment of neuroendocrine side effects of neuroleptics. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1987; 7:91–95Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Baptista T, Lopez ME, Teneud L, Contreras Q, Alastre T, deQuijada M, Araujo de Baptista E, Alternus M, Weiss SR, Musseo E, Paez X: Amantadine in the treatment of neuroleptic-induced obesity in rats: behavioral, endocrine, and neurochemical correlates. Pharmacopsychiatry 1997; 30:43–54Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Baptista T: Body weight gain induced by antipsychotic drugs: mechanisms and management. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1999; 100:3–16Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Meguid MM, Fetissov SO, Varma M, Sato T, Zhang L, Laviano A, Rossi-Fanelli F: Hypothalamic dopamine and serotonin in the regulation of food intake. Nutrition 2000; 16:843–857Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Frankle WG, Gil R, Hackett E, Mawlawi O, Zea-Ponce Y, Zhu Z, Kochan LD, Cangiano C, Slifstein M, Gorman JM, Laruelle M, Abi-Dargham A: Occupancy of dopamine D2 receptors by the atypical antipsychotic drugs risperidone and olanzapine: theoretical implications. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2004; 175:473–480Medline, Google Scholar

10. Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA: The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1987; 13:261–276Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Clinical Guidelines on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults: The Evidence Report: NIH Publication 98–4083. Bethesda, Md, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Sept 1998Google Scholar