Screening for Alcohol Use Disorders Among Medical Outpatients: The Influence of Individual and Facility Characteristics

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Screening of adults in primary care has been recommended to reduce alcohol misuse. This study determined the rates and predictors of alcohol screening, screening positive, follow-up evaluation, and subsequently diagnosed alcohol use disorder in a national sample of Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical outpatients. METHOD: Chart-abstracted quality improvement data from the VA’s 2002 External Peer Review Program were merged with records for 15,580 medical outpatients drawn from 139 VA facilities nationwide. RESULTS: Nearly three-quarters of eligible patients (N=11,553) had chart-documented alcohol screening in the past year. Of these, 4.2% (N=484) screened positive. Of those who screened positive, three-fourths (N=370) received follow-up evaluation, and of these, 53.5% (N=198) were subsequently diagnosed with an alcohol use disorder—1.7% of the originally screened sample. Multivariate logistic regression revealed that several factors generally associated with increased risk of alcohol use disorders—including being younger, unmarried, and disabled, as well as having greater medical and psychiatric comorbidities—were actually associated with a decreased likelihood of alcohol screening. At the facility level, screening was less likely at more academically affiliated centers, and follow-up evaluation of a positive screening was less likely at the largest facilities. CONCLUSIONS: Routine alcohol screening yielded relatively few positive cases, raising questions about its cost-effectiveness. Targeted strategies may increase the value of case-finding activities among patients at greatest risk for alcohol use disorders and at more academically affiliated facilities. Targeted efforts are also needed to ensure proper follow-up evaluation at larger medical centers where patients may experience greater system-level barriers.

Excessive alcohol consumption has been associated with a wide array of adverse outcomes, including serious health problems, accidents, injuries, violence, social problems, disability, and death (1). Annually, in the United States, alcohol misuse is estimated to be responsible for approximately 100,000 deaths (2) and $185 billion in economic costs (3).

Prevalence estimates of alcohol abuse/dependence among medical outpatients typically range from 2% to 9% (4, 5). In addition, up to 10% have been found to engage in harmful drinking and up to 29% in risky drinking, that is, drinking enough to experience or to be at risk for experiencing harm from alcohol use but not enough to meet criteria for abuse/dependence (4, 5). Given the seriousness and prevalence of alcohol problems, coupled with evidence that brief behavioral counseling interventions can be effective in reducing alcohol consumption and improving health outcomes (4, 6), groups such as the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism recommend screening of adults in primary care settings to reduce alcohol misuse (1, 7).

There is by no means a clear consensus on this issue, however. Questions continue to be raised about the effectiveness of alcohol screening in general practice. Indeed, in a recent meta-analysis of screening and brief intervention trials, Beich and colleagues (8) pooled results from the literature and estimated that after 1 year, only two to three patients, out of 1,000 screened, reported drinking less than the maximum recommended level, raising doubts about the effectiveness of screening as a precursor to brief intervention.

Nevertheless, consistent with recommendations for screening, the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), which operates the nation’s largest integrated health care system, requires annual alcohol screening and monitors screening as a quality measure (9), although, here too questions have been raised about the appropriateness of translating general practice guidelines into performance measures (10). With ongoing debate over routine screening for alcohol problems as a backdrop, we set out to examine the “real world” experience of the VA in implementing a large-scale, system-wide policy of screening. In this study, we used available data to follow the chain of events from initial screening to subsequent diagnosis of alcohol use disorder. Specifically, we sought to determine, in a large national sample of VA medical outpatients, the rates and predictors of 1) screening for alcohol problems, 2) positive screenings, 3) follow-up evaluation, and 4) subsequently confirmed diagnoses of alcohol use disorder. By determining the extent to which patients in the VA system are screened and later diagnosed with alcohol use disorders and by identifying factors associated with steps in the pathway, the results of this study are expected to improve our understanding of the screening process in actual, real-world clinical practice.

Method

Data Sources

Data for this study came from VA’s national External Peer Review Program (EPRP), which randomly selects and reviews medical records at all VA facilities on an ongoing basis to monitor the quality and appropriateness of care (11). Trained reviewers abstract paper and/or electronic medical records, looking for evidence of adherence to a variety of performance measures; previous analyses suggest high interrater reliability for these reviews (kappa=0.9) (12). For the present study, we used EPRP data collected during the first three quarters of fiscal year 2002. The overall EPRP sampling frame included all patients who were continuously enrolled in VA heath care for the past 2 years and who had at least one primary care or specialty medical visit in the previous 12 months. Moreover, among eligible patients, two types of sampling were done. First, a large random sample of all patients was obtained to ensure stable estimates for each of the VA’s 22 regional networks (i.e., national representativeness of the data). Then, random samples were obtained of patients with selected high-volume medical conditions (e.g., diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, ischemic heart disease, and hypertension).

Using social security numbers, the EPRP chart-review data were merged with three national VA administrative databases (Patient Encounter File, Outpatient File, and Patient Treatment File). Taken together, these three files document all outpatient and inpatient episodes of care received at VA facilities. The administrative records were used to determine patients’ sociodemographic characteristics, as well as to ascertain clinically assessed medical and mental health diagnoses and service use for the 6 months before and after alcohol screening. For patients who were not screened for alcohol problems, we assigned as their “reference date” (for the purpose of administrative database matching) the average screening date of those who were screened in the same data collection quarter.

Study Sample

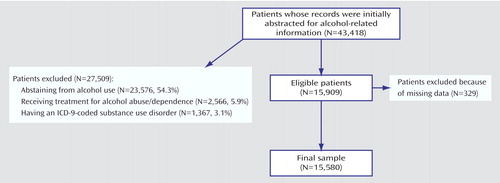

In the EPRP data set, a total of 43,418 patient records were initially abstracted for alcohol-related information. Of these, patients were excluded if, during the past year, they had chart-documented evidence either of completely abstaining from alcohol use (N=23,576, 54.3%) or of receiving treatment for alcohol abuse/dependence, including involvement in support groups such as Alcoholics Anonymous (N=2,566, 5.9%). In addition, using available administrative data, we excluded 1,367 patients (3.1%) who had an ICD-9-coded substance (either alcohol or illicit drug) use disorder (codes 292 and 303–305) in the previous 6-month period. Of the remaining 15,909 eligible patients, we excluded 329 persons (2.1%) who had missing data for one or more study variable (except race), yielding a final sample size of 15,580 (Figure 1). A waiver of informed consent was approved by the institutional review board of the VA Connecticut Healthcare System.

Dependent Variables

We used chart-review data from the EPRP, supplemented with administrative data where indicated, to examine the following cascading series of dichotomous outcomes. First, we determined whether patients had been screened for alcohol problems with a standardized instrument in the past year. Second, among those screened, we determined the proportion that screened positive. Third, among those who screened positive, we determined whether the patient received follow-up evaluation (either chart-review evidence of follow-up or evidence of a specialty mental health visit within 6 months of screening in the administrative data). Finally, among those followed up, we determined the proportion of patients who received a clinical diagnosis of alcohol use disorder (either chart-review evidence or an administrative data diagnosis [ICD-9 codes 303 and 305.0] in the subsequent 6-month period).

Independent Variables

In this study, we considered a broad range of sociodemographic, clinical, and facility-level characteristics as potential predictors of screening for alcohol use disorders and subsequent outcomes.

We included the following sociodemographic variables: age, gender, race, marital status, annual income, and level of VA service connectedness. Information on race was missing for 4,329 individuals; thus, to avoid losing a substantial portion (27.8%) of the sample in multivariate analyses, a separate dummy variable for missing race was included in the modeling process. VA service connection (i.e., the level of compensation for illness or disability associated with military service) was included both as a proxy for functional status and because it confers priority access to VA health care (13).

Using ICD-9-coded administrative records for the 6-month period before the screening or “reference date,” we applied the methodology of Deyo and colleagues (14) to compute the index by Charlson and colleagues (15), a widely used measure to summarize the degree of medical comorbidity. In addition, we determined whether patients had a psychiatric diagnosis (ICD-9 codes 290–291, 293–302, and 306–319).

Finally, we included three VA facility-level variables: academic emphasis (defined as the proportion of funds spent on teaching and research), mental health emphasis (defined as the proportion of funds spent on mental health as contrasted with general health care), and hospital size (defined as the total number of patients treated per year) (16, 17). These factors were hypothesized to influence the likelihood of alcohol screening and subsequent follow-up based on previous research (18), demonstrating their association with the receipt of preventive services for diabetes in the VA system.

Statistical Analysis

We used logistic regression analyses to identify independent predictors of alcohol screening and screening outcomes. Parallel analyses were performed for each of the four outcome measures. The multivariate modeling used generalized estimating equation techniques (19) to account for the clustering of patients within facilities and a backward elimination strategy to determine the most parsimonious set of predictors. Variables that were significant at the 0.05 level were retained in the final models. All analyses were performed by using SAS version 8.

Results

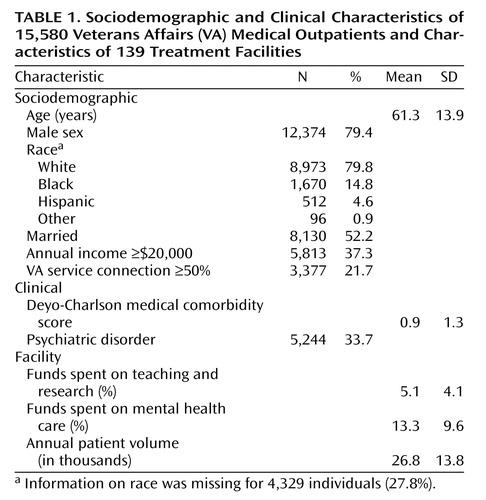

The sample for the present study included 15,580 patients drawn from 139 VA medical centers nationally. Distributions of both individual and facility characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The sample had a mean age of 61.3 years (SD=13.9). The majority of the sample was male, white, married, and of relatively low income. A substantial proportion (21.7%) had at least 50% VA service connection.

Nearly three-quarters of the eligible patients (N=11,553) were screened for alcohol use disorders in the past year (Table 2). Of these, 4.2% (N=484) screened positive. Of those who screened positive, three-fourths (N=370) received follow-up evaluations. Of those followed up, 53.5% (N=198) were subsequently diagnosed with an alcohol use disorder—1.7% of the originally screened sample.

Results of the multivariate analyses are also presented in Table 2. Compared with those age less than 45 years, older persons were significantly more likely to be screened for alcohol problems; however, if screened, they were less likely to screen positive, particularly those ages 65 years and over. The likelihood of being followed up after a positive screening did not differ across age groups, but if followed up, middle-age adults were significantly more likely than those ages <45 years to be diagnosed with an alcohol use disorder. The odds of alcohol screening and subsequent outcomes did not significantly differ by gender, race, or income level, with the exception of a greater likelihood of screening positive among men and black patients.

Married individuals were significantly more likely to be screened; however, they were less likely to screen positive, to be followed up, and to subsequently receive an alcohol use diagnosis. Conversely, veterans with greater service-connected disability and those with a psychiatric disorder were less likely to be screened but more likely to be followed up if they screened positive. Patients with greater medical comorbidity were also less likely to be screened for alcohol problems.

In terms of facility characteristics (Table 2), the likelihood of being screened for alcohol problems was lower at academically affiliated medical centers. Follow-up evaluation of a positive screening was less likely at the largest facilities. Receipt of alcohol screening and subsequent outcomes did not significantly differ with level of funding for mental health care.

Discussion

Using data from a national sample of medical outpatients in the VA system, we sought to evaluate the chain of events from alcohol screening to the diagnosis of alcohol use disorder. In total, three-fourths (74.2%) of the eligible patients had chart-documented alcohol screening in the past year. Of these, 4.2% screened positive. Of those who screened positive, 76.4% received follow-up evaluation, and of these, over half (53.5%) were subsequently diagnosed with an alcohol use disorder, representing 1.7% of the total sample that was screened. This overall rate of diagnosis is somewhat lower than the often-cited prevalence estimates of 2% to 9% for alcohol abuse/dependence in medical outpatient samples (5). In this study, however, a total of 3,933 patients (9.0%) were excluded if they were already known to have a substance use diagnosis and/or were in treatment; thus, the focus was on identifying new cases among at-risk patients.

The relatively low yield raises questions regarding both the value of large-scale, routine screening to detect alcohol problems and the frequency of screening. Beich and colleagues (8) argued that universal screening in general practice is not an effective case-finding strategy. In the present study, for every case that was identified, about 58 persons (11,553÷198) were screened, and nearly two (370÷198) received a follow-up diagnostic evaluation, either in primary care (59.2%) or by a mental health provider (40.8%). To crudely estimate the cost of identifying one case of alcohol use disorder, we assumed the following: 1) each screening cost $4.88, based on the estimate of Valenstein and colleagues (20) for depression screening, and 2) subsequent diagnostic evaluations cost $33.68 if performed in primary care (CPT code 99213) or $138.77 if performed in a specialty mental health clinic (CPT code 90801) with information from the 2000 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule and total facility relative-value units. Under these assumptions, the estimated cost of identifying each case would be $428. Given the health, social, and economic burdens of alcohol misuse, this may well be justified. Unfortunately, detailed treatment and outcome data were not available; thus, a rigorous cost-effectiveness analysis was not possible. Nevertheless, targeted efforts aimed at high-risk patients may improve the overall effectiveness and yield of case-finding activities.

In addition, although the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends screening, it notes that the optimal interval for screening is unknown (7). The low rate of case identification observed in this study may suggest that less-than-annual screening may be a more cost-effective approach, particularly for lower-risk patients.

In the present study, we found that potential risk factors for alcohol problems, such as being younger, unmarried, and disabled, as well as having greater medical and psychiatric comorbidities, were paradoxically associated with a decreased likelihood of alcohol screening. Considerable epidemiological and clinical research has demonstrated strong associations between these characteristics and the prevalence of alcohol use disorders (1, 21, 22). It thus appears that patients who may be at the greatest risk for alcohol abuse and dependence are, in fact, the ones least likely to be screened, and therefore, substantial numbers of cases may be missed.

These findings are consistent with the literature on “competing demands” in the primary care setting (23, 24), which asserts that a patient with multiple problems may receive poorer quality care for a given individual problem because of the competing demands placed on the clinician’s attention. In this view, lack of time is one of the most common barriers to performing a variety of preventive and screening services. At each encounter, clinicians must prioritize the competing demands of acute treatment, clinical preventive services, and patient requests. Given the limited time typically allowed for medical visits, this may be particularly challenging for patients with chronic conditions and multiple complaints.

With respect to the facility characteristics examined, we found a strong negative association between spending on teaching and research and the likelihood of screening patients for alcohol use disorders. One explanation may be that residents, who provide much of the care at academically affiliated facilities, are less likely than attending physicians to adhere to the alcohol screening guideline. Indeed, consistent with this, Burns and colleagues found a similar pattern of association between level of physician training and women’s receipt of screening mammography (25) and clinical breast examination (26). In addition, research and teaching may in some way distract from the provision of clinical preventive services—another example of competing demands. In an earlier study by Linn and Yager (27), the authors found that greater experience treating alcohol problems was associated with less academic work. Another possibility is that many primary care providers express skepticism about the effectiveness of screening and the adequacy of treatment resources (28, 29), and in the present study, this may have been disproportionately true at more academically affiliated medical centers.

Follow-up evaluation of a positive screen is a critical step in properly identifying individuals who have alcohol problems and would benefit from treatment. In this study, we found that only three-fourths of those who screened positive were actually followed up. Facility size was negatively associated with follow-up evaluation of a positive screening. Patients at the largest medical centers may experience greater barriers in terms of factors, such as timely referral and coordination of care, thus decreasing the likelihood of appropriate follow-up.

This study had several limitations. First, our ability to examine variables, such as race, was limited by the quality of the available chart-review and administrative data. Second, the findings may not generalize to non-VA settings. The VA system is unique in several respects, including its use of electronic medical records and clinical reminders for performing preventive services. In addition, the VA is the largest integrated health care system in the country and is geared toward caring for patients with serious mental illness (17), which may, in part, help to explain the lack of association between facility-level variation in mental health spending and the likelihood of alcohol screening and subsequent outcomes. Further studies are needed to determine whether our findings are replicated in non-VA settings.

Third, according to the EPRP chart-review data, over 90% (10,807 of 11,553) of the screenings were performed with the CAGE questionnaire (30); thus, the focus of screening was to detect clinical alcohol abuse/dependence. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test, however, has been shown to be more sensitive in terms of detecting less severe alcohol problems, such as risky and harmful drinking (5, 31, 32). Indeed, the VA now mandates use of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test, or the shortened version (33), as the preferred screening instrument, which will likely increase the identification of patients whose levels or patterns of alcohol consumption do not meet the criteria for abuse/dependence but, nevertheless, place them at increased risk for adverse health and social outcomes. Future work will be needed to ensure that patients with alcohol disorders are not only identified but also followed up and treated appropriately by using therapies that have been shown to be effective in reducing alcohol consumption across the spectrum of alcohol disorders (6). Receipt and adequacy of treatment—the lack of which following systematic identification of problems through screening may be considered unethical—were not assessed in the present study.

Fourth, information was not available on factors such as who performed the screenings. In practice, such screenings are often administered by a VA clinic nurse, which would tend to make screening more cost-effective and less burdensome on providers’ time. In addition, we could not evaluate whether being screened by a regular, familiar provider as opposed to another clinician influenced the likelihood of accurately reporting alcohol problems and of being followed up.

These limitations notwithstanding, the results of this study raise important issues regarding routine annual screening for alcohol problems among medical outpatients. Further work is needed to determine the cost-effectiveness of screening and intervention (34, 35) and the optimal interval for screening in real-world clinical practice, particularly among lower-risk patients, in both VA and non-VA settings. To improve overall effectiveness, targeted strategies may be able to increase case-finding activities among patients who are at greatest risk for alcohol use disorders, as well as among those at more academically affiliated medical centers. Targeted efforts are also needed to ensure proper follow-up evaluation at larger facilities, where patients may experience greater system-level barriers.

|

|

Received July 16, 2004; revision received Oct. 8, 2004; accepted Dec. 2, 2004. From the Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center and the Northeast Program Evaluation Center, VA Connecticut Healthcare System; the Department of Psychiatry and the Department of Epidemiology and Public Health, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, Conn.; and the Office of Quality and Performance, Veterans Health Administration, Washington, D.C. Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. Desai, VA Connecticut Healthcare System, NEPEC (182), 950 Campbell Ave., West Haven, CT 06516; [email protected] (e-mail). Dr. Desai is supported by a Career Development Award from the Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Service (MRP 02-259).

Figure 1. Patients Whose Records Were Initially Abstracted for Alcohol-Related Information and Final Sample of Medical Outpatients Screened for Alcohol Use Disorders

1. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism:10th Special Report to the US Congress on Alcohol and Health: Highlights From Current Research. Rockville, Md, NIAAA,2000Google Scholar

2. McGinnis JM, Foege WH: Mortality and morbidity attributable to use of addictive substances in the United States. Proc Assoc Am Physicians 1999; 111:109–118Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Harwood H: Updating Estimates of the Economic Costs of Alcohol Abuse in the United States: Estimates, Update Methods, and Data. Rockville, Md, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 2000Google Scholar

4. Whitlock EP, Polen MR, Green CA, Orleans T, Klein J: Behavioral counseling interventions in primary care to reduce risky/harmful alcohol use by adults: a summary of the evidence for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med 2004; 140:557–568Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Reid MC, Fiellin DA, O’Connor PG: Hazardous and harmful alcohol consumption in primary care. Arch Intern Med 1999; 159:1681–1689Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Fiellin DA, Reid MC, O’Connor PG: New therapies for alcohol problems: application to primary care. Am J Med 2000; 108:227–237Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. US Preventive Services Task Force: Screening and behavioral counseling interventions in primary care to reduce alcohol misuse: recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 2004; 140:554–556Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Beich A, Thorsen T, Rollnick S: Screening in brief intervention trials targeting excessive drinkers in general practice: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2003; 327:536–542Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Veterans Health Administration: FY 2001 VHA Performance Measurement System Technical Manual. Washington, DC, VHA, 2001Google Scholar

10. Walter LC, Davidowitz NP, Heineken PA, Covinsky KE: Pitfalls of converting practice guidelines into quality measures: lessons learned from a VA performance measure. JAMA 2004; 291:2466–2470Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Halpern J: The measurement of quality of care in the Veterans Health Administration. Med Care 1996; 34(3 suppl):MS55-MS68Google Scholar

12. Jha AK, Perlin JB, Kizer KW, Dudley RA: Effect of the transformation of the Veterans Affairs Health Care System on the quality of care. N Engl J Med 2003; 348:2218–2227Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Hoff RA, Rosenheck RA: Cross-system service use among psychiatric patients: data from the Department of Veterans Affairs. J Behav Health Serv Res 2000; 27:98–106Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA: Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol 1992; 45:613–619Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR: A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987; 40:373–383Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Leslie DL, Rosenheck R: The effect of institutional fiscal stress on the use of atypical antipsychotic medications in the treatment of schizophrenia. J Nerv Ment Dis 2001; 189:377–383Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Rosenheck R, DiLella D: Department of Veterans Affairs National Mental Health Program Performance Monitoring System: Fiscal Year 1999 Report. West Haven, Conn, Northeast Program Evaluation Center, 2000Google Scholar

18. Desai MM, Rosenheck RA, Druss BG, Perlin JB: Mental disorders and quality of diabetes care in the Veterans Health Administration. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159:1584–1590Link, Google Scholar

19. Liang K-Y, Zeger SL: Regression analysis for correlated data. Annu Rev Public Health 1993; 14:43–68Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Valenstein M, Vijan S, Zeber JE, Boehm K, Buttar A: The cost-utility of screening for depression in primary care. Ann Intern Med 2001; 134:345–360Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Mertens JR, Lu YW, Parthasarathy S, Moore C, Weisner CM: Medical and psychiatric conditions of alcohol and drug treatment patients in an HMO: comparison with matched controls. Arch Intern Med 2003; 163:2511–2517Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Bucholz KK: Nosology and epidemiology of addictive disorders and their comorbidity. Psychiatr Clin North Am 1999; 22:221–240Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Klinkman MS: Competing demands in psychosocial care: a model for the identification and treatment of depressive disorders in primary care. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 1997; 19:98–111Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Rost K, Nutting P, Smith J, Coyne JC, Cooper-Patrick L, Rubenstein L: The role of competing demands in the treatment provided primary care patients with major depression. Arch Fam Med 2000; 9:150–154Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Burns RB, Freund KM, Ash A, Shwartz M, Antab L, Hall R: Who gets repeat screening mammography: the role of the physician. J Gen Intern Med 1995; 10:520–522Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Burns RB, Freund KM, Ash AS, Shwartz M, Antab L, Hall R: As mammography use increases, are some providers omitting clinical breast examination? Arch Intern Med 1996; 156:741–744Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Linn LS, Yager J: Factors associated with physician recognition and treatment of alcoholism. West J Med 1989; 150:468–472Medline, Google Scholar

28. Bradley KA, Curry SJ, Koepsell TD, Larson EB: Primary and secondary prevention of alcohol problems: US internist attitudes and practices. J Gen Intern Med 1995; 10:67–72Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Spandorfer JM, Israel Y, Turner BJ: Primary care physicians’ views on screening and management of alcohol abuse: inconsistencies with national guidelines. J Fam Pract 1999; 48:899–902Medline, Google Scholar

30. Ewing JA: Detecting alcoholism: the CAGE questionnaire. JAMA 1984; 252:1905–1907Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Bradley KA, Bush KR, McDonell MB, Malone T, Fihn SD (Ambulatory Care Quality Improvement Project): Screening for problem drinking: comparison of CAGE and AUDIT. J Gen Intern Med 1998; 13:379–388Crossref, Google Scholar

32. Fiellin DA, Reid MC, O’Connor PG: Screening for alcohol problems in primary care: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med 2000; 160:1977–1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Bradley KA, Bush KR, Epler AJ, Dobie DJ, Davis TM, Sporleder JL, Maynard C, Burman ML, Kivlahan DR: Two brief alcohol-screening tests from the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): validation in a female Veterans Affairs patient population. Arch Intern Med 2003; 163:821–829Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Wutzke SE, Shiell A, Gomel MK, Conigrave KM: Cost effectiveness of brief interventions for reducing alcohol consumption. Soc Sci Med 2001; 52:863–870Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Fleming MF, Mundt MP, French MT, Manwell LB, Stauffacher EA, Barry KL: Brief physician advice for problem drinkers: long-term efficacy and benefit-cost analysis. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2002; 26:36–43Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar