The Association of Early Adolescent Problem Behavior With Adult Psychopathology

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The authors investigated whether the association between adolescent problem behavior and adult substance use and mental health disorders was general, such that adolescent problem behavior elevates the risk for a variety of adult disorders, or outcome-specific, such that each problem behavior is associated specifically with an increased risk for disorders clinically linked to that behavior (e.g., early alcohol use with adult alcohol abuse). METHOD: A population-based group of 578 male and 674 female twins reported whether they had ever engaged in, and the age of initiation of, five adolescent problem behaviors: smoking, alcohol use, illicit drug use, police trouble, and sexual intercourse. Participants also completed a structured clinical interview at both ages 17 and 20 covering substance use disorders, major depressive disorder, and antisocial personality disorder. Data were analyzed with simple bivariate methods, survival analysis, and structural equation analysis. RESULTS: Each problem behavior was significantly related with each clinical diagnosis. The association was especially marked for those who had engaged in multiple problem behaviors before age 15. Among those with four or more problem behaviors before age 15, the lifetime rates of substance use disorders, antisocial personality disorder, and major depressive disorder exceeded 90%, 90%, and 30% in males and 60%, 35%, and 55% in females, respectively. The association between the clinical diagnoses and adolescent problem behavior was largely accounted for by two highly correlated factors. CONCLUSIONS: Early adolescent problem behavior identifies a subset of youth who are at an especially high and generalized risk for developing adult psychopathology.

Adolescent problem behavior, especially when expressed early, is associated with an increased risk of adult behavioral problems. For example, early adolescent smoking is associated with higher rates of adult nicotine dependence (1), alcohol use before age 15 is associated with a substantial increase in the risk of adult alcoholism (2–5), early delinquent behavior is predictive of adult antisocial personality disorder (6, 7), and early initiation of sexual behavior increases the risk of unwanted pregnancy and sexually transmitted disease (8, 9). But to some degree, these associations are self-evident because the adult outcomes investigated parallel the adolescent problem behaviors with which they have been linked. That is, it is not altogether surprising to find, for example, that those who started to smoke early in life are most likely to become addicted to nicotine given that initiation to smoking is essentially a precursor to nicotine dependence.

Several lines of evidence, however, suggest that the association of early adolescent problem behavior with adult psychopathology may reflect general rather than specific mechanisms of risk. First, there is a strong co-occurrence among multiple indicators of adolescent problem behavior, implying the existence of an underlying dimension of problem behavior (10–12). Similarly, there is growing evidence that the strong comorbidity among multiple common psychiatric and substance use disorders can be accounted for by one or more underlying dimensions of mental health (13, 14). Finally, at least one indicator of adolescent problem behavior—early alcohol use—is a general rather than specific risk factor for adult psychopathology because alcohol use before age 15 is associated with substantially increased risk not only for alcoholism but also for drug abuse, antisocial personality disorder, and academic underachievement (4).

The present study seeks to further test the hypothesis that the relationship of adolescent problem behavior with adult psychopathology is general rather than specific by investigating multiple indicators of adolescent problem behavior (use of tobacco, use of alcohol, trouble with police, sexual initiation, and illicit drug use) and multiple indicators of adult psychopathology (nicotine dependence, alcohol abuse or dependence, drug abuse or dependence, antisocial personality disorder, and major depressive disorder) in a large sample of twins assessed at both age 17 and 20. Specifically, we sought 1) to determine whether involvement in multiple aspects of adolescent problem behavior is associated with increased general versus specific risk for adult psychopathology and, if so, 2) to estimate the strength of those associations.

Method

Participants

The participants were drawn from the Minnesota Twin Family Study, an ongoing longitudinal study of like-sex adolescent twins and their parents. Twins were ascertained from Minnesota state birth records between 1971 and 1985, with over 90% of twin families located for each relevant birth year. The families were eligible to participate if they lived within a day’s drive of the University of Minnesota and if the twins had no disabling physical (e.g., blindness) or psychological (e.g., mental retardation) condition that precluded their completing our day-long intake assessment. Among the eligible families, approximately 17% refused our invitation to participate. A comparison of participants and nonparticipants on various demographic, socioeconomic, and mental health indicators showed that participating parents were slightly, but significantly, better educated than the nonparticipating parents (mean difference of less than 0.3 years of education), but the two types of families did not differ in self-reported mental health (15).

The Minnesota Twin Family Study intake sample included an 11-year-old and a 17-year-old cohort, only the latter of which was used in the present study. There were 674 female (average age of 17.5 years, SD=0.5) and 578 male (average age of 17.5, SD=0.4) twins who completed the intake assessment. The present report analyzes the twins as individuals and does not make use of the different types of twins to try and infer genetic and environmental contributions to phenotypic differences. A follow-up assessment was scheduled approximately 3 years after the twins’ intake assessments. Follow-ups were completed on 630 (94%, average age of 20.7 years, SD=0.6) of the female and 481 (83%, average age of 20.7 years, SD=0.5) of the male twins. Nonparticipating twins were significantly more likely than participating twins to have 1) had an intake diagnosis of drug abuse/dependence in the female sample only, 2) satisfied the criteria for antisocial personality disorder (ignoring the age-18 requirement) in the male sample only, and nicotine dependence in both samples. The two groups of twins did not, however, differ significantly in the intake rates of major depressive disorder or alcohol abuse/dependence. Typical of Minnesota for the birth years sampled, over 98% of the twins were Caucasian. At both assessments, the participants gave their informed consent, or if they were younger than 18, they gave their assent to participate after the study procedures had been described.

Assessments

Five indicators of adolescent problem behavior were obtained through self-reports at the age-17 assessment. These were 1) tobacco use (“Have you ever tried tobacco?”), 2) alcohol use (“Have you ever used alcohol without parental permission?”), 3) police contact (“Other than for traffic violations, have you ever been in trouble with the police?”), 4) use of any of 10 illicit substances (separate assessment for marijuana, amphetamines, barbiturates, tranquilizers, cocaine, heroin, opiates, phencyclidine [PCP], psychedelics, and inhalants), and 5) sexual intercourse (“Have you ever had intercourse?”). In addition to reporting whether they had ever engaged in each of these activities, the adolescents also reported age at first occurrence. Responses to each indicator were coded on a 3-point scale: 1=engaged in the problem behavior at least once before age 15, 2=engaged in the problem behavior for the first time after age 14, and 3=had not engaged in the problem behavior by the time of the age-17 assessment. There was a small amount of missing data for each behavioral problem indicator because of nonresponse or failure to ask the relevant question.

At both intake and follow-up, diagnostic data were obtained with structured clinical interviews administered by trained master’s- and bachelor’s-level interviewers. Structured interviews included the expanded substance abuse module, developed by Robins et al. (16) as a supplement to the World Health Organization’s Composite International Diagnostic Interview (17) for substance use disorders, the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (18) to cover adolescent- or adult-onset depression, and the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R Personality Disorders antisocial personality disorder section, as modified to include additional probes and follow-up questions to flesh out symptoms of conduct disorder and antisocial behavior since age 15 (19). Five diagnostic outcomes are investigated: 1) nicotine dependence, 2) alcohol abuse or dependence, 3) drug abuse or dependence (i.e., abuse or dependence on any of the following: amphetamines, cannabis, cocaine, hallucinogens, inhalants, opiates, PCP, and sedatives), 4) antisocial personality disorder (assessed ignoring the requirement that individuals be at least 18 years old), and 5) major depressive disorder. Diagnostic criteria were evaluated in consensus case conferences and lifetime diagnoses assigned according to DSM-III-R criteria, the diagnostic standard current at the time that the Minnesota Twin Family Study was started. Except for substance abuse diagnoses, which require only a single positive symptom, lifetime diagnoses were considered positive if either all (definite level of certainty) or all but one (probable level of certainty) of the DSM-III-R symptom criteria were met. The inclusion of probable diagnoses was meant to minimize false negatives in a sample of young adults who had not yet experienced the full period of risk for the disorders we assessed. We investigated the reliability of our diagnostic procedures and found kappas ≥0.90 for antisocial personality disorder and substance abuse and dependence diagnoses and >0.80 for major depressive disorder (15).

Statistical Analysis

The relationship of adolescent problem behavior and adult psychopathology was assessed at both the individual and aggregate level. First, the relationship of each of the five behavioral problem indicators with each of the five diagnostic outcomes was investigated with logistic regression with problem indicator, gender, and their interaction as independent variables and lifetime diagnosis by the age-17 assessment as the dependent variable. The correlated nature of the twin data was taken into account with hierarchical linear methods as incorporated into PROC GENMOD from the Statistical Analysis System (SAS) (20). Significant effects were followed up with pairwise comparisons of the three problem behavior groups separately in the male and female samples to determine how the groups with early, late, and no problem behaviors differed.

Second, to assess the combined effect of early initiation of adolescent problem behavior, we computed an index of the number of problem behaviors engaged in before age 15 and related this index to each of the five diagnostic outcomes with life table (survival analysis) methods from the SAS LIFETEST procedure. In these analyses, the proportion of individuals affected with each diagnosis (and associated standard error) was estimated at age 17 and age 20 with the product-limit method (21). To adjust for missing data, the individuals unaffected at intake who did not participate at follow-up were included as censored observations. The homogeneity of the survival curves across the multiple levels of the index was tested with the log-rank test (21).

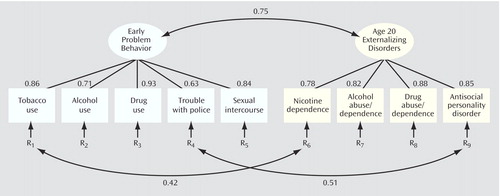

Finally, the aggregate relationship of early adolescent problem behavior and adult psychopathology was assessed with a two-factor model where the first factor loaded on the five adolescent problem behaviors and the second factor loaded on all age-20 diagnoses except major depressive disorder (Figure 1). Previous research supports the existence of two broad dimensions of adult psychopathology: externalizing, which loads on the substance diagnoses and antisocial personality disorder; and internalizing, which loads on depression and the anxiety disorders (13, 14). Major depressive disorder was not included in the factor model because a single indicator of internalizing is not sufficient to identify this factor in the model. In addition to the two common factors, the model allowed for a specific residual correlation between each adolescent problem behavior and its corresponding adult diagnosis (i.e., between early smoking and nicotine dependence, between early alcohol use and alcohol diagnosis, between early drug use and drug diagnosis, and between both early police contact and sex and antisocial personality disorder). The factor model was fit with the Mx software system (22) with input estimates of tetrachoric and polychoric correlations and associated asymptotic variance-covariance matrix from PRELIS based on the method described by Neale and Maes (23). Model fit was judged by the goodness of fit chi-square statistic; the Akaike information criterion, which balances model fit and parsimony; and the root mean square error of approximation, which assesses the agreement between the observed correlations and those predicted by the model. A nonsignificant goodness of fit, negative Akaike information criterion, and root mean square error of approximation <0.05 are all indications of good model fit (22).

Results

Indicators of Problem Behavior and DSM Diagnoses

The rates of early (younger than age 15), late (ages 15 to 17), and no onset of adolescent problem behavior are given separately for male and female subjects in Table 1. The rates vary markedly across the multiple indicators, with tobacco use before age 15 being relatively common (approximately 50% of the sample) and early sexual intercourse and illicit drug use being relatively uncommon (approximately 5% of the sample). The rates of early problem behavior were generally higher in the male than the female subjects, although this difference was not statistically significant for illicit drug use and sexual intercourse.

The rates of definite plus probable DSM-III-R diagnoses as a function of status on each of the five adolescent problem behaviors (early, late, or never) and associated odds ratios are given in Table 2. The odds ratio gives the proportionate increase in the odds of having a diagnosis for a 1-unit change in the problem indicator. In all 25 cases, there was a significant association between adolescent problem behavior and the rate of diagnosis, and since the gender-by-problem behavior interaction was statistically significant in only two of 25 cases, the nature of this relationship appears to be similar for male and female subjects. Since antisocial personality disorder requires evidence of conduct disorder before age 15, we investigated the relationship between the problem indicators and a diagnosis of adult antisocial behavior based on symptoms of adult antisocial behavior manifest after age 15. Adult antisocial behavior was significantly associated with all of the early problem behaviors, indicating that the conduct disorder criteria do not account fully for the association of antisocial personality disorder with adolescent problem behavior. Odds ratios generally exceed 4.0 for externalizing psychopathology and 2.0 for major depressive disorder, indicating that adolescent problem behavior and early-onset adult psychopathology were strongly related. Post hoc comparisons within the male and female samples further underscored the consistent pattern of results: the rates of diagnosis were highest among the early problem initiators, intermediate among the late initiators, and lowest among those who had not engaged in the behavior by the age-17 assessment. To further document the especially strong prognostic significance of early problem behavior, each of the five disorders was predicted in a logistic regression that included as independent variables sex, the number of early problems, and the number of late problems. In every case, the odds ratio for early problems was greater than the odds ratio for late problems (significantly so for more than half of the early-late comparisons), and early problems were significantly associated with outcome even after the effects of late problems had been taken into account.

The Aggregate Effect of Early Problem Behavior

Early problem behaviors were highly intercorrelated, with the mean tetrachoric correlation among the indicators of problem behavior before age 15 being 0.55 (range=0.42 to 0.72) in male subjects and 0.64 (range=0.52 to 0.75) in female subjects. An index of early involvement in problem behavior was computed by summing the number of problem behaviors each participant had engaged in before age 15. Although the scores on this index could range from 0 to 5, scores of 4 and 5 were combined for analysis because few individuals (three males and six females) had engaged in all five problem behaviors before age 15. Males (mean=1.02, SD=1.02) scored significantly higher than females (mean=0.76, SD=1.00) on this index (t=4.61, df=1217, p<0.001).

The life table analysis of the relationship between the number of problem behaviors before age 15 and the rates of lifetime diagnoses at age 17 and 20 is summarized in Table 3. In both the female and male samples, survival curves varied significantly at p<0.001 across the multiple levels of the early problem behavior index score. Among those with a high index score, the rates of clinical diagnoses were high at age 17 and continued to rise through age 20. Among women at the age-20 assessment with four or five early problem behaviors, the lifetime rates were 82% for nicotine dependence, 61% for alcohol abuse or dependence, 84% for drug abuse or dependence, 35% for antisocial personality disorder, and 57% for major depressive disorder. The comparable rates for 20-year-old men with four or five early problem behaviors were 92%, 92%, 100%, 92%, and 33%, respectively.

The full two-factor model fit the observed data well (χ2=24.6, df=21, p>0.25; Akaike information criterion=–17.4; root mean square error of approximation=0.013). Three of the residual correlations (early use of alcohol with alcohol diagnoses, early drug use with drug diagnoses, and early sexual experience with antisocial personality disorder) could be deleted from the model without significantly decreasing the model fit (change in χ2=2.9, df=3, p>0.05); Figure 1 gives the standardized parameter estimates from this latter model. The standardized loadings were uniformly high for both the early problem behavior and the age 20 externalizing psychopathology factors, supporting the existence of the two underlying factors. The moderate or nonsignificant magnitude of the residual correlations in comparison to the strong factor correlation of 0.75 indicates that the association of early problem behavior and adult psychopathology owes primarily to the correlation in the underlying factors.

Discussion

We investigated mental health outcomes associated with adolescent substance use, sexuality, and trouble with police in a sample of 1,252 adolescents and found that adolescent problem behavior, especially when expressed early, is associated with substantial increases in the risk of nicotine dependence, alcohol abuse or dependence, drug abuse or dependence, major depressive disorder, and antisocial personality disorder by age 20. Regardless of the specific problem behavior, the earlier an adolescent engages in that behavior, the more likely he or she is to have a substance use disorder, major depressive disorder, and antisocial personality disorder diagnosis in early adulthood. These findings support the general nature of risk for common mental disorders and underscore the prognostic significance of early adolescent problem behavior.

Research has convincingly shown that multiple indicators of adolescent problem behaviors are strongly intercorrelated (10, 24–26) and that multiple indicators of adult externalizing psychopathology are strongly intercorrelated (13, 14). We have extended this literature by showing that the two domains are themselves highly related. Each of the five indicators of adolescent problem behavior was significantly associated with each of the five diagnostic outcomes we investigated. For substance use disorders and antisocial personality disorder, these associations were quite strong, with odds ratios generally exceeding 4.0. For major depressive disorder, the strength of the association was weaker (odds ratios generally between 2.0 and 3.0) but still statistically significant. These results clearly show that adolescent problem behavior is associated with a generalized—rather than a specific—risk of adult psychopathology.

Further support for the generalized nature of the association between the two domains comes from the correlated factor model we fit. Each of the five adolescent problem behaviors loaded strongly (0.63 to 0.93) on a single adolescent problem behavior factor, and each of the four externalizing diagnoses loaded strongly (0.78 to 0.88) on a single externalizing psychopathology factor. The relationship between the two domains was attributed primarily to a strong correlation (r=0.75) between the two latent factors. Once the factor correlation had been taken into account, the only significant residual correlations were those between early smoking and nicotine dependence and early police contact and antisocial personality disorder. We interpret these findings as providing strong support for the existence of general mechanisms linking adolescent problem behavior and disinhibitory psychopathology in adulthood.

A second striking feature of our data is the age-at-onset effect: adolescent problem behavior before age 15 is associated with a substantially increased risk of adult disorders. This effect is particularly salient when the multiple problem behaviors are aggregated. Among men who reported having engaged in four or five adolescent problem behaviors before the age of 15, the rates of substance use diagnoses and antisocial personality disorder all exceeded 80% at age 20, while the rate of major depressive disorder exceeded 30% by age 20. Among 20-year-old women with four or five early problem behaviors, the rates of substance use diagnoses exceeded 60%, the rate of antisocial personality disorder exceeded 30%, and the rate of major depressive disorder exceeded 55%. It is possible that individuals who engaged in early problem behavior have higher rates of diagnoses than individuals who did not because they have had more time to progress from initial symptom expression to disorder onset. Nonetheless, our survival analyses showed that the relatively high disorder rates at age 17 continued to rise through age 20 for individuals with a large number of early adolescent problem behaviors. Our findings are thus consistent with other research in suggesting that the early initiation of adolescent problem behavior is associated with increased risk and not simply earlier onset of adult psychopathology (27).

Although our findings convincingly establish a link between adolescent problem behavior and adult psychopathology, they do not establish the causal basis for this association. Some have hypothesized that early adolescent problem behavior directly increases the risk for adult psychopathology by disrupting normal developmental processes (2). Alternatively, others have hypothesized that the link between early adolescent problem behavior and adult psychopathology owes to a common, perhaps inherited, liability (5). Resolving these possibilities will require longitudinal observations in genetically informative samples, something we plan to pursue in future research. Despite their causal ambiguity, our findings do have implications for prevention scientists. Clearly, the expression of multiple problem behaviors early in life identifies a group that is at a very high risk of developing substance use disorders, antisocial personality disorder, and major depressive disorder. Moreover, the generality of both the nature of adolescent problem behavior as well as its adult outcomes suggests that interventions or prevention strategies targeted at single behaviors (e.g., youth smoking or sexual initiation) may, even if successful, not fully ameliorate psychopathology risk among problem youth.

There are several limitations to our research design that should be taken into account when interpreting our results and considering their generalizability. First, although our sample is broadly representative of Minnesota families, it does not represent the full range of ethnic diversity that exists in the United States. Second, our assessment of adolescent problem behavior was based on retrospective report. The well-known limitations of retrospective reports (e.g., telescoping) (28) underscore the need for prospective designs.

|

|

|

Received Feb. 1, 2004; revision received June 2, 2004; accepted June 14, 2004. From the Department of Psychology, University of Minnesota. Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. McGue, Department of Psychology, University of Minnesota, 75 East River Rd., Minneapolis, MN 55455; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported in part by U.S. Public Health Service grants AA-00175, AA-09367, and DA-05147.

Figure 1. Two-Factor Model of Adolescent Problem Behavior and Externalizing Psychopathology at Age 20a

aIndicators of early problem behavior refer to whether and at what age adolescents engaged in each of five problem behaviors: early use of tobacco, alcohol, and illicit drugs and early contact with police and engaging in sexual intercourse. Indicators of psychopathology at age 20 refer to lifetime diagnoses made at either a definite or probable level of certainty for nicotine dependence, alcohol abuse or dependence, illicit drug abuse or dependence, and antisocial personality disorder. Values given are standardized parameter estimates; all parameter estimates reported are statistically significant. This model fit the data well (χ2=27.5, df=24, p=0.28).

1. Breslau N, Fenn N, Peterson EL: Early smoking initiation and nicotine dependence in a cohort of young adults. Drug Alcohol Depend 1993; 33:129–137Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. DeWit DJ, Adlaf EM, Offord DR, Ogborne AC: Age at first alcohol use: a risk factor for the development of alcohol disorders. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:745–750Link, Google Scholar

3. Grant BF, Dawson DA: Age at onset of alcohol use and its association with DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: results from the National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey. J Subst Abuse 1997; 9:103–110Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. McGue M, Iacono WG, Legrand LN, Elkins I: The origins and consequences of age at first drink, I: associations with substance-use disorders, disinhibitory behavior and psychopathology, and P3 amplitude. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2001; 25:1156–1165Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Prescott CA, Kendler KS: Age at first drink and risk for alcoholism: a noncausal association. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 1999; 23:101–107Medline, Google Scholar

6. Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Dickson N, Silva P, Stanton W: Childhood-onset versus adolescent-onset antisocial conduct problems in males: natural history from ages 3 to 18 years. Dev Psychopathol 1996; 8:399–424Crossref, Google Scholar

7. Taylor J, Iacono WG, McGue M: Evidence for a genetic etiology of early-onset delinquency. J Abnorm Psychol 2000; 109:634–643Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Brooks-Gunn J, Furstenberg FF: Adolescent sexual behavior. Am Psychol 1989; 44:249–257Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Greenberg J, Magder L, Aral S: Age at first coitus: a marker for risky sexual behavior in women. Sex Transm Dis 1992; 19:331–334Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Donovan JE, Jessor R: Structure of problem behavior in adolescence and young adulthood. J Consult Clin Psychol 1985; 53:890–904Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Burt SA, Krueger RF, McGue M, Iacono WG: Sources of covariation among attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, and conduct disorder. J Abnorm Psychol 2001; 110:516–525Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Young SE, Stallings MC, Corley RP, Krauter KS, Hewitt JK: Genetic and environmental influences on behavioral disinhibition. Am J Med Genet Neuropsychiatr Genet 2000; 96:684–695Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Krueger RF: The structure of common mental disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999; 56:921–926Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Kendler KS, Prescott CA, Myers J, Neale MC: The structure of genetic and environmental factors for common psychiatric and substance use disorders in men and women. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003; 60:929–937Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Iacono WG, Carlson SR, Taylor J, Elkins IJ, McGue M: Behavioral disinhibition and the development of substance use disorders: findings from the Minnesota Twin Family Study. Dev Psychopathol 1999; 11:869–900Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Robins LN, Baber T, Cottler LB: Composite International Diagnostic Interview: Expanded Substance Abuse Module. St Louis, Washington University, Department of Psychiatry, 1987Google Scholar

17. Robins LN, Wing J, Wittchen HU, Helzer JE, Babor TF, Burke J, Farmer A, Jablenski A, Pickens R, Regier DA, Sartorius N, Towle LH: The Composite International Diagnostic Interview: an epidemiologic instrument suitable for use in conjunction with different diagnostic systems and in different cultures. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988; 45:1069–1077Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID). New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1987Google Scholar

19. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MB: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R Personality Disorders (SCID-II). New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1989Google Scholar

20. Liang KY, Zeger SL: Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika 1986; 73:13–22Crossref, Google Scholar

21. Kalbfleisch JD, Prentice RL: The Statistical Analysis of Failure Time Data. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1980Google Scholar

22. Neale MC, Boker SM, Xie G, Maes HH: Mx: Statistical Modeling. Richmond, Medical College of Virginia, Department of Psychiatry, 1999Google Scholar

23. Neale MC, Maes HHM: Methodology for Genetic Studies of Twins and Families. Dordrecht, the Netherlands, Kluwer Academic (in press)Google Scholar

24. Hanna EZ, Yi H, Dufour MC, Whitmore CC: The relationship of early-onset regular smoking to alcohol use, depression, illicit drug use, and other risk behaviors during adolescence: results from the youth supplement to the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Subst Abuse 2001; 13:265–282Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Robins LN: Deviant Children Grown Up. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins, 1966Google Scholar

26. Windle M: A longitudinal study of antisocial behaviors in early adolescence as predictors of late adolescent substance use: gender and ethnic group differences. J Abnorm Psychol 1990; 99:86–91Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Anthony JC, Petronis KR: Early-onset drug use and risk of later drug problems. Drug Alcohol Depend 1995; 40:9–15Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Groves RM: Survey Errors and Survey Costs. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1989Google Scholar