Response to Emotional Stimuli in Boys With Conduct Disorder

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Boys with conduct disorder are at risk of persistently showing antisocial behavior in adult life, particularly if they have an additional diagnosis of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). In the search for biological risk factors that predispose children to the development of antisocial personality disorder, research has provided substantial data suggesting that autonomic hyporesponsiveness indicates a greater likelihood of future antisocial behavior. The purpose of this study was to examine autonomic arousal in boys with conduct disorder, comorbid conduct disorder and ADHD, and ADHD only. METHOD: In addition to self-ratings, electrodermal responses to pleasant, neutral, and unpleasant slides were obtained for 21 boys with conduct disorder and 54 boys with ADHD plus conduct disorder. Forty-three boys with a diagnosis of ADHD only were recruited as a clinical comparison group, and 43 boys with no conduct disorder or ADHD were included as a healthy comparison group. All subjects were ages 8–13 years. RESULTS: Compared to the healthy subjects and the subjects with ADHD only, the boys with conduct disorder and with ADHD plus conduct disorder reported lower levels of emotional response to aversive stimuli and lower autonomic responses to all slides independent of valence. CONCLUSIONS: Although the self-report data supported a deficit in reactivity to explicit fear cues, the psychophysiological data indicated that boys with conduct disorder both with and without a comorbid condition of ADHD are characterized by a generalized deficit in autonomic responsivity in an experimental situation in which children were exposed to complex visual stimuli of unpredictable affective quality. Psychophysiological findings may point to a deficit in associative information processing systems that normally produce adaptive cognitive-emotional reactions.

As many as 50% of boys with conduct disorder continue to show antisocial behavior as young adults (1), and the risk of antisocial personality development is even higher if antisocial behavior starts before age 10 years (2). Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) has also long been associated with a higher risk of antisocial outcome (3). However, a growing amount of data suggest that although there is indeed a close relationship between conduct disorder and antisocial personality disorder, no connection exists between ADHD and antisocial personality disorder (4). The inconsistency in previous study findings could result from not considering the presence of comorbid conduct disorder in children with ADHD.

Progress has been made in uncovering biological risk factors in children that predispose them to developing antisocial personality disorder as grown-ups. In the field of psychophysiology, research has provided substantial data suggesting that lower levels of autonomic arousal (e.g., low resting heart rate), as well as autonomic hyporesponsiveness, indicate a greater likelihood of future antisocial behavior (5, 6). In antisocial adolescents and adults, low responses to neutral and aversive stimuli have been found (7, 8). In a previous study we found that boys with conduct disorder only and boys with comorbid ADHD and conduct disorder show low levels of electrodermal responses to orienting stimuli (i.e., nonprominent acoustic tones) and low levels of response to aversive tones but that boys with ADHD only did not differ from healthy comparison subjects on these measures (9, 10). Fowles et al. (5) suggested that there may be two attentional deficits in antisocial individuals of any age, one deficit with respect to attending to neutral stimuli and another deficit with respect to the anticipation of aversive events. In the search for factors underlying electrodermal hyporesponsiveness in antisocial individuals, temperamental dimensions, such as fearlessness, low levels of inhibitory control, or executive function deficits, have been discussed (5, 11), and these dimensions may in turn give a predisposition toward antisocial behavior.

Case reports of patients with orbitofrontal damage who consistently showed an absence of punishment-related learning led Damasio et al. (12) to establish the so-called somatic marker hypothesis. According to this hypothesis, somatic marker signals help in the anticipation of option-outcome scenarios with respect to punishment and reward (13). Electrodermal hyporesponsiveness may be a relevant somatic marker, because individuals with “acquired sociopathy” after orbitofrontal cortex lesions were found to show low levels of autonomic responses to both positively and negatively valenced visual stimuli. Antisocial behavior in children has also been associated with amygdalar dysfunction, on the basis of findings of selective impairments in the processing of sad and fearful facial expressions (14).

The objective of the current study was to examine psychophysiological responses as well as self-report measures of response to emotional stimuli (pictures of pleasant, neutral, and unpleasant phenomena) in 8–13-year-old boys with an exclusive diagnosis of conduct disorder or with the comorbid condition of ADHD plus conduct disorder, compared with children with ADHD only and healthy comparison subjects. ADHD children were chosen as a clinical comparison group for two reasons: 1) to control for probable psychophysiological effects related to the failure to adequately allocate attention to experimental stimuli and 2) because the choice of a comparison group with another extraversive disorder would possibly lead to findings that are specific for antisocial behavior. We had the specific hypothesis that children with conduct disorder and children with ADHD plus conduct disorder who viewed emotional pictures would report lower levels of emotional arousal on self-rating scales and would show lower levels of autonomic responses, compared with subjects with ADHD only and healthy comparison subjects.

Method

Subjects

One hundred forty Caucasian boys ages 8–13 years with a diagnosis of externalizing behavior problems were screened for participation in the study. They had been consecutively admitted to the inpatient and outpatient clinics of the Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry at Aachen University over a period of 2.5 years. Exclusion criteria were as follows: WISC-III verbal and performance IQ below 85, medical disorder (particularly a neurological disorder), and additional relevant mental disorder (i.e., psychosis, tics, anxiety or mood disorder) assessed by using a German standardized interview, the Diagnostic Interview for Psychiatric Disorders in Childhood and Adolescence (15). In addition, all children underwent an extensive pediatric examination, including screening for receptive or expressive language disorders, and, if indicated, they were referred for additional neurolinguistic assessment. Although some of the children had a sigmatism or a history of stuttering, none of the children in the current study fulfilled the criteria for a receptive language disorder. Furthermore, it was particularly important to exclude children with anxiety disorders because this comorbid condition might modulate psychophysiological responsiveness. Finally, 21 boys with conduct disorder and 54 boys with ADHD plus conduct disorder were recruited as the two experimental groups, and 43 boys with a diagnosis of ADHD only were included as a clinical comparison group. In addition, 43 male healthy comparison subjects were randomly recruited in local primary and secondary schools. The healthy comparison subjects were assessed with the Diagnostic Interview for Psychiatric Disorders in Childhood and Adolescence and the Diagnostic System for Mental Disorders in Childhood and Adolescence (16) to rule out psychiatric disorders. All interviews were conducted by a senior child and adolescent psychiatrist. Eighty-five percent (N=82) of the subjects with a diagnosis of ADHD only or ADHD plus conduct disorder were drug naive; 15% (N=15) had taken methylphenidate in the past but had been free of any medication for a minimum of 2 weeks at the time of testing. All conduct disorder subjects and healthy comparison subjects were drug naive.

The diagnostic procedure was identical to the one described in detail previously by Herpertz et al. (9). To receive a diagnosis of conduct disorder, ADHD, or ADHD plus conduct disorder, boys had to fulfill the diagnostic criteria presented in DSM-IV, including those related to age at onset. The Diagnostic System for Mental Disorders in Childhood and Adolescence was used as a standardized diagnostic instrument. This very commonly used German instrument is based on a semistructured interview of parents. It covers all DSM-IV items listed in the corresponding diagnostic categories and subsumes a severity score for each item ranging from 0 to 3. In our study this interview was conducted by a senior child and adolescent psychiatrist who was blind to the subject’s clinical diagnosis and was trained in administering the instrument. The reliability of diagnoses was tested by using the blind test-retest reliability paradigm in a subgroup of children, i.e., the parents of 10 randomly selected children in each diagnostic group were reinterviewed by an independent rater (experienced child and adolescent psychiatrist trained in this interview) who was unaware of the prior diagnoses. Significant associations were found for all symptoms, with correlation coefficients for the number of fulfilled symptoms and symptom severity scores ranging between 0.87 and 0.95. The two raters’ agreement on the diagnostic grouping was good (Cohen’s kappa of 0.90). Subjects who fulfilled a sufficient number of the criteria for both disorders were assigned a diagnosis of ADHD plus conduct disorder. All conduct disorder and ADHD plus conduct disorder children fulfilled the criteria for early-onset conduct disorder (starting before age 10 years). To recruit clinical groups with rather homogeneous severity of psychopathology, children who merely fulfilled the criteria for oppositional defiant disorder without additionally meeting the criteria for conduct disorder were excluded. A further inclusion criterion was established for the ADHD and the ADHD plus conduct disorder groups by using the Conners’ Teachers and Parents Rating Scales (17). Children had to have a score 15 or greater on the parent scale or the teacher scale and a summary score of 30 or greater to be included in the study. The Child Behavior Checklist (18) was used to obtain further information on externalizing and internalizing symptoms from the parents.

To assess additional characteristics that might have an influence on psychophysiological responses and the likelihood of developing antisocial behavior, two self-report measurements were used: the Anxiety Questionnaire for Pupils (19) and the Depression Inventory for Children and Adolescents (20), a German adaptation of the Children’s Depression Inventory. Both questionnaires were read to the children. The investigation, for which the children were required to stay in the laboratory for at least 30 minutes, was carried out in accordance with the latest version of the Declaration of Helsinki, and the study design was reviewed by the local ethics committee. Children and their parents gave written informed consent for the children to participate after receiving a comprehensive description of the study.

Emotional Stimuli and Study Design

Stimulus material consisted of 18 slides from the International Affective Picture System (21). In a preliminary study of 100 randomly selected 8–13-year-old pupils, the slides applied in the present study were proven to reliably provoke emotional responses (22). The stimulus pool included six pleasant (exciting sports activities, family scenes, pets), six neutral (work situations, agriculture, surroundings), and six unpleasant images (crying and wounded children, people in despair, violent scenes). Slides appeared for 6 seconds each in random order. After each slide, the subjects were asked to rate the intensity of their affective response by using the Self-Assessment Manikin (23). This visual analog scale consists of self-report ratings for valence and arousal; the valence scale ranged from feeling extremely unpleasant (score=0) to feeling extremely pleasant (score=5), and the arousal scale ranged from a state of very low emotional arousal (score=0) to a state of very high arousal (score=5).

Psychophysiological Recordings

Physiological measures of skin conductance and heart rate activity were recorded by a modular system (ZAK Medical Technics, Marktheidenfeld, Germany). Physiological signals were recorded with Ag-AgCl electrodes—miniature electromyogram electrodes and 1-cm skin conductance electrodes—filled with electrode gel (Spectra 360, Parker Laboratories, Fairfield, N.J.). Impedances were kept below 5 kΩ . To record skin conductance activity, electrodes were centered on the thenar and hypothenar eminences of the nondominant hand; activity was sampled every 20 msec. The magnitude of the skin conductance response was defined as the largest increase from baseline within 0.9 and 4 seconds of the presentation of the stimulus standardized to the intraindividual maximum. The intraindividual maximum was assessed within the same experiment to control for influences related to the subjects or the environment that may change over time—children’s mood or motivation, in particular. Finally, values were transformed logarithmically to improve the symmetry of the distribution curves. An amplitude exceeding 0.02 μS was considered to indicate an elicited response (24). Heart rate signals, recorded from the left forefinger by an infrared sensor, were regarded as an ancillary measure, because they are sensitive not only to changes in affective state but also to task demands. The signals were sampled at 50 Hz and were rectified and integrated with a time constant of 0.3 seconds within a measuring range of 1 mV. Heart rate activity was defined as the mean change during the first 3 seconds after the appearance of each slide, compared with the mean for the 3-second baseline period immediately preceding the slide’s appearance. Subjects were seated comfortably in a light- and sound-attenuated room where temperature and humidity levels were kept constant.

Data Analyses

All variables were tested for normal distribution. Because some psychophysiological variables were not distributed normally, the main effects of analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were controlled by using nonparametric statistical procedures. To detect group differences in clinical characteristics and symptom severity, the four diagnostic groups were compared by using one-way ANOVAs with post hoc tests (Tukey’s honestly significant difference test, with control for the type I error rate). To examine changes in self-report and physiological measures as a function of the affective valence of the stimuli, in addition to group effects, repeated-measures ANOVAs were used for the experimental data, with diagnostic group as a between-subjects factor and slide valence category (pleasant, neutral, unpleasant) as a within-subject factor. In case of nonsphericity, the Greenhouse-Geisser or Huynh-Feldt correction procedure was performed (each time considering the more conservative correction). Because of our specific hypothesis that the conduct disorder and conduct disorder plus ADHD groups would differ from both the ADHD only and healthy comparison groups, contrasts were used to test the combined conduct disorder and ADHD plus conduct disorder groups against the others. This procedure was performed in relation to total responses over all slide categories and to each of the three slide valence categories. The level of significance was set at p=0.05. If a main effect was observed for diagnosis with regard to age, IQ, or relevant state variables of anxiety or depression, the influence of the variable on overall group differences in physiological data was analyzed by means of analysis of covariance. All statistical analyses were performed with SAS 6.12 (SAS Institute, Cary, N.C.).

Results

Diagnostic Data

The subjects’ demographic and diagnostic data are summarized in Table 1. There were group effects for age and intelligence. The ADHD boys were significantly younger than the conduct disorder boys, and the healthy comparison subjects were more intelligent than the other three groups, which were highly comparable with each other.

Data from all subscales of the diagnostic instrument (Diagnostic System for Mental Disorders in Childhood and Adolescence) confirmed significant overall group effects (p<0.0001). Post hoc Tukey’s tests revealed that, consistent with the design, the boys with conduct disorder only differed in ADHD symptoms from the boys with comorbid ADHD and conduct disorder. With regard to the conduct disorder symptoms, the boys with the comorbid condition showed more severe symptoms than those with conduct disorder only, and this difference reached the level of significance with regard to oppositional defiant behavior. By design the ADHD plus conduct disorder group did not differ from the ADHD group in the three ADHD criteria of attention deficit, hyperactivity, and impulsivity, but they differed in the severity of the two symptom criteria of conduct disorder (oppositional defiant behavior and conduct disorder behavior). Further diagnostic data based on the Conners’ Teachers and Parents Rating Scales supported the Diagnostic System for Mental Disorders in Childhood and Adolescence data, as they consistently showed that children with ADHD did not differ from those with ADHD plus conduct disorder in the severity of ADHD symptoms. Data from the Child Behavior Checklist showed a highly significant overall group effect on the externalizing and internalizing subscales, with all clinical groups differing from the healthy comparison subjects on both dimensions of psychopathology. Again, the ADHD plus conduct disorder group exhibited the most severe symptoms, with higher scores on the externalizing and internalizing subscales than the groups with conduct disorder only and ADHD only.

Self-report data showed no overall group differences on the anxiety scale. However, an overall group effect was found for the severity of depression (F=3.75, df=3, 157, p=0.01), although the mean values of all groups were still a long way from the pathological range (T score >60). Post hoc pairwise comparisons indicated that the boys with ADHD plus conduct disorder scored significantly higher than the healthy comparison subjects but that there was no difference between the clinical groups.

Emotional Ratings

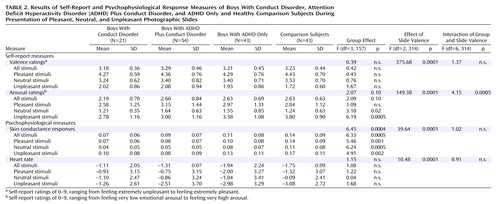

The slides selected from the International Affective Picture System were suitable for inducing various emotional ratings in 8–13-year-old boys. This finding was reflected in the repeated-measures ANOVA by the overall effect for slide valence category, which was significant for valence and arousal. For the valence ratings, neither a group effect nor an interaction effect (interaction of group and slide valence) was found (Table 2). However, although contrasts did not show significant differences with regard to total valence ratings (F=0.03, df=1, 157, p=0.85), the combined conduct disorder and conduct disorder plus ADHD groups evaluated the negative pictures less aversively than did the combined ADHD only and healthy comparison groups, although this result did not reach significance (F=2.68, df=1, 157, p=0.10).

The overall group effect concerning arousal ratings approached significance, and there was a significant interaction of group and slide valence (Table 2). The interaction effect was particularly produced by the ADHD plus conduct disorder group, which, relative to the healthy comparison group, gave higher ratings to the pleasant pictures and, particularly, to the neutral pictures but lower ratings to the unpleasant pictures. The ADHD only group reported a similar, but less marked, arousal pattern in response to the various slide categories. The conduct disorder group reported the lowest ratings for all slide valence categories. In a test of our specific hypothesis, contrasts showed that the combined conduct disorder and conduct disorder plus ADHD groups rated the pictures as less arousing, relative to the combined ADHD only and healthy comparison groups (F=3.66, df=1, 157, p=0.05). Considering each slide category, the combined conduct disorder and conduct disorder plus ADHD groups evaluated only negative slides as significantly less arousing (F=14.99, df=1, 157, p=0.0002); no difference was found with regard to positive stimuli (F=0.03, df=1, 157, p=0.85) and neutral stimuli (F=0.05, df=1, 157, p=0.82).

In contrast to intelligence and depressive state (measured with the Depression Inventory for Children and Adolescents), age had an influence on subjective arousal ratings for negative slides (F=3.66, df=1, p=0.05) in the covariance analysis. However, the effect of age alone is not likely to be sufficient to explain the group differences, because the overall group effect remained significant (F=5.69, df=3, 157, p=0.001).

Psychophysiological Data

An overall effect of slide valence was found, indicating that skin conductance responses were a function of slide valence category. Repeated-measures ANOVA revealed a main overall group effect but no interaction effect (Table 2). Contrasts indicated that compared to the combined groups of ADHD boys and healthy comparison subjects, the combined groups of boys with conduct disorder only and with ADHD plus conduct disorder showed lower total electrodermal responses (F=12.81, df=1, 157, p=0.0005) as well as lower responses to each of the slide valence categories (pleasant: F=10.46, df=1, 157, p=0.001; neutral: F=15.03, df=1, 157, p=0.0002; negative: F=9.14, df=1, 157, p=0.003). Heart rate was modulated by the various slide valence categories; however, group effects were not found.

Age, intelligence, and depression were not found to be significant covariants of electrodermal response to the emotional stimuli (age: p=0.78; IQ: p=0.60; Depression Inventory for Children and Adolescents score: p=0.26).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the first to assess self-report and autonomic measures of emotional responses to experimental stimuli in boys with conduct disorder. Special features of the study included the differentiation between conduct disorder boys with and without the comorbid condition of ADHD and the introduction of a clinical comparison group of ADHD children in addition to healthy comparison subjects. Our data indicate that compared to healthy comparison subjects and ADHD children, conduct disorder boys with and without comorbid ADHD reported lower levels of emotional response to aversive pictures only and showed lower intensity of autonomic responses to all categories of pictures independent of valence. In addition, our psychometric data indicate that children with the comorbid condition of ADHD plus conduct disorder are characterized by more severe behavioral disturbances than children with conduct disorder only, a finding that supports previous work by Pliszka et al. (25).

According to the self-report data, the combined groups of conduct disorder and ADHD plus conduct disorder boys rated negative pictures as less arousing than the other two groups, and they tended to evaluate these pictures as less aversive. These findings are consistent with the theory of fearlessness in antisocial individuals of any age and may reflect an insensitivity toward potentially frightening events, which may interfere with anticipation of danger (26). Furthermore, the two ADHD groups gave higher arousal ratings to neutral stimuli, but lower ratings to negative stimuli, compared with healthy comparison subjects, producing an interaction of group and slide valence. Conduct disorder boys reported the lowest arousal ratings throughout, indicating that children with pure conduct disorder generally experience low levels of arousal or experience indifference in response to pictures. These differential results suggest that self-ratings of emotional stimuli in children with conduct disorder are more likely to reflect real emotional experiences, compared to those of adults with personality disorder diagnoses, who do not differ in self-ratings of emotional stimuli from healthy comparison subjects and therefore appear to possess associative processing faculties that allow stimulus-appropriate evaluations (27).

As for the findings on autonomic responses, our hypothesis that children with conduct disorder would exhibit a specific deficit in responding to affective stimuli was not supported, i.e., we failed to find an interaction of group by slide valence in the electrodermal data. Conduct disorder children with and without an additional diagnosis of ADHD showed low levels of response to aversive stimuli but also to emotional (both positive and negative) stimuli in general and to neutral pictures, as well. Therefore, the deficit in conduct disorder children that accounts for electrodermal hyporeactivity may extend beyond a failure to anticipate future punishment or reward and points to a generalized autonomic hyporesponsivity in this experimental situation.

The difference in findings between the two applied sets of measurements—self-report and autonomic responsiveness—again supports the observation of a dissociation between measures of emotional and physiological reactivity (28) and reinforces the long recognized need in the emotion literature to examine multiple response domains. One could speculate that boys with conduct disorder with and without ADHD report low levels of arousal to negative pictures in particular because these appraisals fit their self-image of being fearless, tough, and “cool” (29). Psychophysiological data, however, which are closer to basic information processing systems than are self-ratings, suggest that hyporesponsiveness is not restricted to a failure to identify aversive events

To guide research to identify the underlying deficit of autonomic hyporesponsivity, one hypothesis, focused on attention deficit, is that antisocial individuals are characterized by a fundamental deficit in allocating attentional resources to stimuli (5). However, this view may be questioned, because the autonomic responses of ADHD children without coexistent conduct disorder did not differ from those of comparison subjects, even though the ADHD children had severe attentional deficits. Alternatively, decreased autonomic responses in the conduct disorder and ADHD plus conduct disorder children may reflect the way children process complex stimuli that may signal an emotionally potent event. Our results support the findings of Schmidt et al. (30), who reported low levels of response to nonemotional tones in undersocialized aggressive children, and they are consistent with data previously obtained by our research group in an analogous study design in which adults with psychopathy exhibited a generalized deficit in electrodermal responsivity (31). Therefore, the general autonomic hyporeactivity we found in the conduct disorder children with and without ADHD may reflect a deficit in associative processing systems that respond to complex cueing contexts, as was found by Patrick and Lang (32) in their study of adult antisocial individuals.

Autonomic hyporesponsiveness appears to be a highly reliable correlate of childhood conduct disorder and adult psychopathy; however, the underlying deficit is far from clear. Some methodical limitations need to be considered, as well, concerning demographic and clinical characteristics of our cohort. As in other studies (33), the comparison subjects had a higher IQ than the clinical groups, although this difference had no influence on group effects in psychophysiological data. The boys with conduct disorder only were older than the boys in the other groups, and this age difference was significant in the comparison between the conduct disorder only and ADHD only groups. However, the age distribution was typical of child psychiatric samples. The broad majority of children under the age of 12 who meet the criteria for conduct disorder also meet the criteria for ADHD (34). Again, covariance analyses indicated that psychophysiological data were not confounded by differences in age. In addition, the group sizes were quite heterogeneous because of the selection bias associated with a clinical population in which conduct disorder comorbid with ADHD is more likely to occur than is pure conduct disorder. Klein et al. (35), who sought to find a group of children with pure conduct disorder for a research study, discovered that 69% of the conduct disorder group concurrently had ADHD.

In summary, our data indicate that conduct disorder children with and without ADHD, but not children with ADHD only, are characterized by a response deficit when exposed to complex visual stimuli of unpredictable affective quality.

|

|

Received April 16, 2003; revisions received Sept. 2, 2003, and April 4, 2004; accepted May 19, 2004. From the Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Rostock University; and the Departments of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy and of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Aachen University, Aachen, Germany. Address correspondence and reprint requests to Prof. Dr. Herpertz, Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Rostock University, Gehlsheimer Str. 20, D-18147 Rostock, Germany; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by grant HE 2660/3–1 from the German Research Foundation and a grant from the Interdisciplinary Center for Clinical Research, RWTH Aachen (IZKF BIOMAT). The authors thank D. Cardaci, I. Juette, T. Kirsten, V. Kuhnen, S. Leger, J. Leycik, R. Loehrer, T. Vloet, and A. Kathoefer for medical assistance and A. Schuerkens and K. Willmes for statistical support.

1. Langbehn DR, Cadoret RJ, Yates WR, Troughton EP, Stewart MA: Distinct contributions of conduct and oppositional defiant symptoms to adult antisocial behavior. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998; 55:821–829Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Kazdin AE: Conduct Disorders in Childhood and Adolescence, 2nd ed. London, Sage, 1996Google Scholar

3. Weiss G, Hechtman T: Hyperactive Children Grown Up: ADHD in Children, Adolescents, and Adults. New York, Guilford, 1993Google Scholar

4. Kim-Cohen J, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Harrington H, Milne BJ, Pulton R: Prior juvenile diagnoses in adults with mental disorder: developmental follow-back of a prospective-longitudinal cohort. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003; 60:709–717Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Fowles DC, Kochanska G, Murray K: Electrodermal activity and temperament in preschool children. Psychophysiology 2000; 37:777–787Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Raine A: Annotation: the role of prefrontal deficits, low autonomic arousal, and early health factors in the development of antisocial and aggressive behavior in children. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2002; 43:417–434Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Raine A, Venables PH, Williams M: Autonomic orienting responses in 15-year-old male subjects and criminal behavior at age 24. Am J Psychiatry 1990; 147:933–937Link, Google Scholar

8. Hare RD, Frazelle J, Cox DN: Psychopathy and physiological responses to threat of an aversive stimulus. Psychophysiology 1978; 15:165–172Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Herpertz SC, Wenning B, Mueller B, Qunaibi M, Sass H, Herpertz-Dahlmann B: Psychophysiological responses in ADHD boys with and without conduct disorder: implications for adult antisocial behavior. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2001; 40:1222–1230Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Herpertz SC, Müller B, Wenning B, Qunaibi M, Lichterfeld C, Herpertz-Dahlmann B: Autonomic responses in boys with externalizing disorders. J Neural Transm 2003; 110:1181–1195Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Moffitt TE, Lynam D: The neuropsychology of conduct disorder and delinquency, in Progress in Experimental Personality and Psychopathology Research. Edited by Fowles D, Sutker P, Goodman S. New York, Springer, pp 233–262Google Scholar

12. Damasio AR, Tranel D, Damasio H: Individuals with sociopathic behavior caused by frontal damage fail to respond autonomically to social stimuli. Behav Brain Res 1990; 41:81–94Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Bechara A, Damasio H, Damasio AR: Emotion, decision making and the orbitofrontal cortex. Cereb Cortex 2000; 10:295–307Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Blair RJR, Morris JS, Frith CD, Perrett DI, Dolan R: Dissociable neural responses to facial expression of sadness and anger. Brain 1999; 122:882–893Crossref, Google Scholar

15. Unnewehr S, Schneider S, Margraf J: Diagnostic Interview for Psychiatric Disorders in Childhood and Adolescence. Berlin, Springer, 1995Google Scholar

16. Doepfner M, Lehmkuhl G: Diagnostic System for Mental Disorders in Child and Adolescence According to ICD-10 and DSM-IV (DISYPS-KJ). Bern, Switzerland, Huber, 1998Google Scholar

17. Conners CK: Rating scales for use in drug studies with children. Psychopharmacol Bull 1973; 9:24–84Google Scholar

18. Achenbach TM, Edelbrock C: Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist and Revised Child Behavior Profile. Burlington, University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry, 1983Google Scholar

19. Wieczerkowski W, Nickel H, Janowski A, Fittkau B, Rauer W: Angstfragebogen für Schüler (AFS), 4th ed. Göttingen, Germany, Hogrefe, 1974Google Scholar

20. Stiensmeier-Pelster J, Schürmann M, Duda K: Depressions-Inventar für Kinder und Jugendliche (DIKJ), 2nd ed. Göttingen, Germany, Hogrefe, 2000Google Scholar

21. Center for the Study of Emotion and Attention (CSEA): The International Affective Picture System: Digitized Photographs. Gainesville, University of Florida, 1999Google Scholar

22. Mueller B, Wenning B, Schuerkens A, Herpertz-Dahlmann B, Herpertz SC: Validierung und Normierung von kindgerechten, standardisierten Bildmotiven aus dem International Affective Picture System. [Validation and norms of standardized pictures from the International Affective Picture System suitable for children.] Z Kinder Jugendpsychiatr 2004; 32:235–243Crossref, Google Scholar

23. Lang PJ: Behavioral treatment and biobehavioral assessment: computer applications, in Technology in Mental Health Care Delivery. Edited by Sidowski JB, Johnson JH, Williams TA. Norwood, NJ, Albex, 1980, pp 109–137Google Scholar

24. Turpin G, Schaefer F, Boucsein W: Effects of stimulus intensity, risetime, and duration on autonomic and behavioral responding: implications for the differentiation of orienting, startle, and defense responses. Psychophysiology 1999; 36:453–463Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Pliszka SR, Carlson CL, Swanson JM: ADHD With Comorbid Disorders: Clinical Assessment and Management. New York, Guilford, 1999Google Scholar

26. Raine A: Autonomic nervous system factors underlying disinhibited, antisocial, and violent behavior. Ann NY Acad Science 1996; 794:46–59Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Herpertz SC, Kunert HJ, Schwenger UB, Sass H: Affective responsiveness in borderline personality disorder: a psychophysiological approach. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:1550–1556Link, Google Scholar

28. Quas JJ, Hong M, Alkon A, Boyce WT: Dissociation between psychobiologic reactivity and emotional expression in children. Psychobiology 2000; 37:153–175Crossref, Google Scholar

29. Cohen D, Strayer J: Empathy in conduct disordered and comparison youth. Dev Psychol 1996; 32:988–998Crossref, Google Scholar

30. Schmidt K, Solanto MV, Bridger WH: Electrodermal activity of undersocialized aggressive children. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1985; 26:653–660Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Herpertz SC, Werth U, Lukas G, Qunaibi M, Schuerkens A, Kunert HJ, Freese R, Flesch M, Mueller-Isberner R, Osterheider M, Sass H: Emotion in criminal offenders with psychopathy and borderline personality disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001; 58:737–745Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Patrick CJ, Lang AR: Psychopathic traits and intoxicated states: affective concomitants and conceptual links, in Startle Modification: Implications for Neuroscience, Cognitive Science, and Clinical Science. Edited by Dawson M, Schell A. New York, Cambridge University Press, 1999, pp 209–230Google Scholar

33. Schachar R, Mota VL, Logan GD, Tannock R, Klim P: Confirmation of an inhibitory control deficit in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Abnorm Child Psychol 2000; 28:227–235Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Reeves JC, Werry JS, Elkind GS, Zametkin A: Attention deficit, conduct, oppositional, and anxiety disorders in children, II: clinical characteristics. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1987; 26:144–155Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Klein RG, Abikoff H, Klass E, Ganeles D, Seese LM, Pollack S: Clinical efficacy of methylphenidate in conduct disorder with and without attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1997; 54:1073–1080Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar