Predictors of Antidepressant Use Among Older Adults: Have They Changed Over Time?

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Antidepressant use increased substantially among older adults with the introduction of the new-generation medications such as the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. The authors analyzed data from two follow-up intervals—1986–1987 to 1989–1990 (interval 1) and 1992–1993 to 1996–1997 (interval 2)—from a community-based cohort of 4,162 older adults to determine predictors of future antidepressant use. METHOD: Information on antidepressant use, demographic and health characteristics, and categories of depressive symptoms—positive affect, negative affect, somatic complaints, and interpersonal problems—were obtained. Logistic regression was used to control simultaneously for multiple variables predicting antidepressant use during the two intervals. Repeated-measures logistic regression (with generalized estimating equations) was employed to model the probability of antidepressant use, with adjustment for the effect of time. RESULTS: Prior antidepressant use and white race were strong predictors of future use during both intervals. Negative affect was the only additional significant predictor of use during interval 1. In contrast, low positive affect scores, cognitive impairment, and poorer health were additional significant predictors during interval 2. In a repeated-measures model, race, prior antidepressant use, poor health, low positive affect scores, and somatic complaints varied as predictors over time. Negative affect and cognitive impairment were consistent predictors over time. CONCLUSIONS: The predictors of antidepressant use by older adults changed over time, with health-related measures of quality of life, such as positive affect, health status, and somatic complaints, becoming more prominent as predictors of use.

Antidepressants are among the most frequently prescribed medications in the United States across the life cycle (1, 2). Their use increased substantially beginning in the late 1980s, in large part because of the introduction of the new-generation antidepressant medications such as the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (3). In 2002, antidepressants were the third-ranking therapy class worldwide, experiencing an 18% sales growth in 2000, with North America as the dominant market (4).

We previously published results from a community-based survey of an elderly cohort documenting an increase in use of antidepressants from 1986–1987 to 1996–1997, noting the significant increase in use of antidepressants in this cohort and the marked differences in antidepressant use by race (5). In that study we found that factors associated with antidepressant use varied somewhat from 1986–1987 to 1996–1997. In 1986–1987, antidepressant use was associated with cognitive impairment, female sex, fair to poor perceived health, white race, and higher education. Depressive symptoms were not associated with use. (If the symptoms for which the drug is prescribed improve, then the absence of an association of use with overall depression scores is not surprising.) In 1996–1997 we found that white race and physical disability were associated with use. Given that we found no cross-sectional association between the overall burden of depressive symptoms and antidepressant use, we questioned whether specific depressive symptoms were predictors of antidepressant use over time. The overall burden of depressive symptoms may be relieved by medications, yet persistent symptoms could predict future use. In addition, people who are not taking medications could experience depressive symptoms that predict use in the future. The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D Scale) (6) can be used to explore the potential association between types of depressive symptoms and use of antidepressants, as described later in the Method section.

A person may receive a diagnosis of major depression whether or not he or she experiences specific symptoms, such as sleep disturbance or feelings of guilt, as long as five of the DSM-IV-TR symptom criteria are met and the person experiences symptoms that are considered clinically significant. Depressive symptoms, however, range across a spectrum that includes depressed mood (such as feeling depressed), anhedonia and loss of interest, psychomotor disturbances (such as agitation or retardation), cognitive dysfunction (such as memory difficulties and confusion), and negative views of the world and the self (such as hopelessness and low self-esteem) (7). Depression can also contribute to problems relating to others in the social network (8). The CES-D Scale has been shown to have a four-factor structure reflecting this diversity of symptoms; the four factors are positive affect, negative affect, somatic complaints, and interpersonal problems (6, 9).

We therefore studied a cohort of elderly people from the Duke Established Populations for Epidemiologic Studies of the Elderly, a sample drawn in the Piedmont of North Carolina in 1986 and followed for 10 years. During this follow-up, information on antidepressant use was gathered on four occasions: P1 (1986–1987), P2 (1989–1990), P3 (1992–1993), and P4 (1996–1997). The dates of these interviews permitted us to consider depressive symptoms as predictors of future antidepressant use, while controlling for possible confounders, during two intervals: interval 1 (from 1986–1987 to 1989–1990), before the significant increase in the use of the new-generation antidepressants, and interval 2 (1992–1993 to 1996–1997), during the rapid rise in the use of the new-generation antidepressants. We hypothesized that the core symptoms of depression, specifically negative affect and somatic complaints, would predict future use of antidepressants, even with adjustment for important covariates, such as prior use of antidepressants, race, cognitive impairment, and education (variables that we previously found to be associated with antidepressant use in cross-sectional analysis) (5). We also hypothesized that, with the introduction of the new-generation antidepressants, some of the predictors of future antidepressant use would change over time, specifically that factors other than the core symptoms of depression would be predictive of future use during interval 2.

Method

Participants

Data for this study are from the Duke Established Populations for Epidemiologic Studies of the Elderly (10, 11). The Duke sample consisted of community residents selected from five contiguous Piedmont counties in North Carolina, one of which was predominantly urban and the other four predominantly rural. The Duke Established Populations for Epidemiologic Studies of the Elderly was a 10-year prospective cohort study. The sampling design has been described in detail previously (10). Briefly, the study used a four-stage probability sample of 4,162 people age ≥65 years, 54% of whom were African American. (With the exception of 26 subjects, all designated their race as either white or African American. Those who designated their race as “other” were categorized with the white subjects in this analysis.) A baseline interview was conducted in 1986–1987, and three additional in-person interviews were conducted in 1989–1990, 1992–1993, and 1996–1997. All subjects (or their designated proxy respondents) signed a written consent form approved by the Duke Institutional Review Board.

Measures

A comprehensive demographic section of the interview assessed age, sex, race, and education. The demographic variables at baseline were dichotomized and coded as follows: age (1=65–74 years, 2=≥75 years), self-designated race (1=white/other, 2=African American), and education (1=≥9 years, 2=<9 years). Health status was measured with a health index that assessed the weighted number of chronic illnesses self-reported by the subject and was trichotomized, with lower values indicating better medical status (12). Cognitive status was assessed with the 10-item Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire (13). The scale score was dichotomized (1=three or more errors, 0=less than three errors) (13).

Depression

Depression was assessed by using a modified version of the CES-D Scale (6, 11). The modified version included all 20 items from the original scale and is highly comparable to the original version (11). Subjects answered the items by responding either yes or no, rather than using the four options from the original scale, for a range of scores from 0 to 20. Radloff (6) and Weissman et al. (9) explored the factor structure of the original 20-item scale and identified four factors: 1) positive affect—four items (felt as good as other people, felt hopeful about the future, felt happy, and enjoyed life), 2) negative affect—seven items (could not shake the blues, felt depressed, thought life was a failure, felt fearful, felt lonely, had crying spells, and felt sad), 3) somatic complaints—seven items (bothered by things, appetite poor, trouble concentrating, felt everything an effort, sleep restless, talked less than usual, and could not get going), and 4) interpersonal problems—two items (people were unfriendly and felt people disliked me). This factor structure was confirmed in the Duke Established Populations for Epidemiologic Studies of the Elderly sample (14). The ranges of scores for the four subscales were 0–4 for positive affect, 0–7 for negative affect, 0–7 for somatic complaints, and 0–2 for interpersonal problems. The positive affect scale was recoded so that higher scores indicated more depressive symptoms on all four subscales. In a previous study we found that the positive affect scale score predicted 3-year mortality, whereas the other scale scores did not, suggesting that the score on each subscale may have unique value as a variable (15).

All scale scores were entered as continuous variables in the logistic regression modeling, so the odds ratios can be interpreted as the relative odds of antidepressant use per change of one unit (symptom) for each scale. The four subscales were intercorrelated, with the highest bivariate correlation between the negative affect scale and the somatic scale (r=0.60). The positive affect scale was only modestly correlated with the negative affect scale (r=0.28), the somatic scale (r=0.25), and the interpersonal scale (r=0.12).

Medications

As part of the interview, participants were asked whether they had taken any medicines prescribed by a doctor or any other medicines obtained from a store during the previous 2 weeks. If they responded “yes,” the participants were asked to show the interviewer these medications (16, 17). The interviewer recorded the drug name, dosage form, and number of dosage forms the respondent reported taking the previous day. For prescription drugs, the interviewer also recorded from the label the drug strength, whether the participant’s name was on the label, and whether the medicine was prescribed to be taken regularly or as needed. Details about the procedure have been published elsewhere (16).

Antidepressants were categorized as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants, and “other antidepressants.” Monoamine oxidase inhibitors, stimulants, and lithium were not included in the analysis because of the very low frequency of use (<0.1%). We determined use of antidepressants from computerized files of participants’ self-reported prescription drug data coded by using an updated and modified version of the Drug Product Information Coding System (16, 18, 19). Of those subjects interviewed during interval 1, a total of 3,017 provided data on antidepressant use (use/no use) both in 1986–1987 and 1989–1990. Of those subjects interviewed during interval 2, a total of 1,540 provided data on antidepressant use both in 1992–1993 and 1996–1997.

Statistical Analyses

For this study, data from each interview were first analyzed as two longitudinal studies of the same cohort, over the periods of interval 1 (from 1986–1987 to 1989–1990) and interval 2 (from 1992–1993 to 1996–1997). The analyses proceeded in four phases. In the first phase, the data were summarized by means or percentages for all covariates for interval 1 and interval 2. Unadjusted odds ratios for antidepressant use at follow-up were then calculated for all covariates. Next, logistic regression was used to estimate the direct effect of each of the independent variables on antidepressant use at follow-up for each of the two intervals. All variables were entered in the regression analysis simultaneously. Finally, a repeated-measures logistic regression model (with generalized estimation equations or generalized estimating equations under PROC GENMOD in SAS [20]) was employed.

Results

Among participants for whom antidepressant data were available (that is, subjects who reported use/no use) during interval 1, 86 (2.9%) reported antidepressant use in 1986–1987 and 134 (4.5%) reported such use in 1989–1990. Among participants in interval 2, 66 (4.3%) reported antidepressant use in 1992–1993 and 125 (8.1%) reported such use in 1996–1997. Among subjects taking antidepressants at 1986–1987, 57% were also taking them 3 years later. Among subjects taking antidepressants in 1992–1993, 47% were taking them 4 years later.

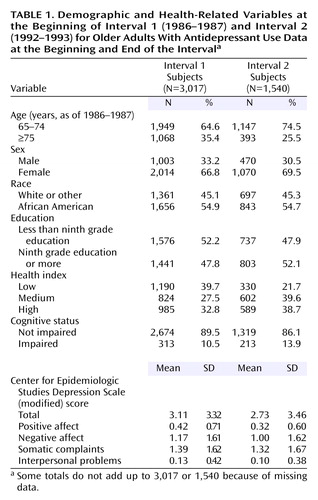

The demographic characteristics of the samples are presented in Table 1. Data are presented for those subjects for whom antidepressant data were available for both interviews during interval 1 or both interviews during interval 2. As would be expected, subjects in interval 2 were younger and more likely to be female than the subjects in interval 1, reflecting the survival characteristics of the cohort. With aging, the cohort was more likely to report poorer self-rated health and more likely to be cognitively impaired. Scores on the entire CES-D Scale and the four subscales were slightly better at the beginning of interval 2 than at the beginning of interval 1.

As Table 2 shows, bivariate predictors from logistic regression analysis of antidepressant use during both intervals included white race (African American race was “protective” against use), cognitive impairment, negative affect, and antidepressant use at the beginning of the interval (by far the strongest predictor). The overall CES-D Scale score (entered as a continuous variable) and the somatic complaint scale score were significant predictors of future use during interval 1 and interval 2. In contrast, higher education (lower education was “protective” against use), poorer health index, and low positive affect scores were significant predictors of future use during the interval 2.

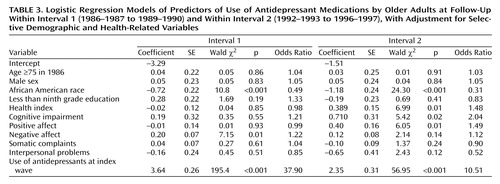

The full logistic models shown in Table 3 demonstrate a clearly different pattern of predictors for interval 1, compared to interval 2. Prior antidepressant use and race remain strong predictors during both intervals. Negative affect was the only additional significant predictor of future use during interval 1. In contrast, negative affect was not a significant predictor for the later time period. Poor health index, cognitive impairment, and low positive affect scores were significant predictors. In a separate analysis, the composite CES-D Scale was a significant predictor in the full model during interval 1 but not interval 2.

To accommodate a repeated-measures design, we used a generalized estimating equations model in which we entered the CES-D Scale subscale scores, cognitive status measures, the health index, and data on use of antidepressant medications at the index wave as time-varying covariates along with demographic variables. A term classified as “interval” was then entered as a separate variable (coded 1 for the first interval and 2 for the second) to control for the effect of time. In the initial full repeated-measures model, interval (time) was a highly significant predictor of future use (p<0.0001). In addition, race (p<0.0001), use of an antidepressant at the index wave (p<0.0001), cognitive impairment (p<0.03), and negative affect (p=0.008) were significant predictors of future use. To determine if these effects were stable over time, we entered 11 interaction terms simultaneously (one term for each covariate by interval) to determine if, as a set, the interaction terms were significant additions to the model (21). We conducted a log-likelihood ratio test with 11 degrees of freedom; the result was significant, indicating that one or more of the interaction terms was significant on a multiplicative scale. We next did a series of generalized estimating equations models and removed nonsignificant interaction terms, one step at a time, until all the remaining terms in the model were significant (21). The final model is presented in Table 4. We found that cognitive impairment and negative affect were significant as main effects in the model. The interaction terms for interval-by-race, taking antidepressants at the beginning of the interval, the health index, low positive affect scores, and high somatic complaint scores were each significant, suggesting that the effects of these factors varied over time. The effect of race, poor health, and low positive affect scores increased over time, while the effects of taking an antidepressant at the beginning of the interval and of high somatic complaint scores decreased over time.

Discussion

The findings of this study expand our earlier findings (5) by documenting that white race was not only a correlate but also a strong predictor of antidepressant use and that the predictive strength of that variable increased from interval 1 (1986–1987 to 1989–1990) to interval 2 (1992–1993 to 1996–1997). In addition, previous antidepressant use predicted future use, although the predictive strength of that variable decreased from interval 1 to interval 2. We also confirmed our first hypothesis: the negative affect scale score predicted future antidepressant use regardless of interval. In contrast, the somatic complaints scale score was more predictive during interval 1 than during interval 2. Cognitive function was a predictor of future antidepressant use, perhaps reflecting the relatively high frequency of clinically significant depressive symptoms as cognitive dysfunction increases (22, 23).

The positive affect scale score and chronic illness became significant predictors of antidepressant use during interval 2, with increased use of antidepressants in this cohort. These findings follow the trend of using the new-generation antidepressant medications for a wider range of problems. The greater safety of these agents may have increased use in people with chronic illnesses. Greater safety also may lead to greater use among persons with subthreshold depression (24, 25).

The positive affect scale score may reflect overall physical and psychological well-being. Scoring low on these items may therefore suggest either a reaction to a less than optimal psychosocial environment or a perception that “things are just not as they should be.”

The strengths of this study include good response rates in a cohort of older adults living in one geographic area throughout the duration of the study. We used two analytic approaches to facilitate understanding of the data. The first permitted “eyeball” comparison of change over time across the two intervals; the second, a more sophisticated longitudinal analytic approach, took into account in a single analysis all changes that occurred since the start of the study.

There are a number of problems in the study design that could bias the results. First, follow-up occurred over 3–4 years, and many factors can intervene during these intervals to either increase or decrease the likelihood that the subjects will take antidepressants in the future, such as the occurrence of a first-time episode of major depression with no prior known risk. The subjects who reported on use of antidepressants during interval 2, compared to those who participated during interval 1, were older, as survivors were more healthy than nonsurvivors. They were less healthy and slightly more cognitively impaired than subjects who reported use of antidepressants during interval 1, as would be expected. They also scored slightly lower on the four CES-D Scale subscales. In our previous study (5) we did not find age to be a significant predictor of antidepressant use when other factors were controlled. We do not know how long participants used antidepressants. Some subjects may have taken the drugs for the entire 3–4 years, others for the short periods that were captured in the follow-up interviews, and still others might have stopped and started use during the study. In addition, we have no data on the efficacy of the medications in symptom reduction. We only have data on medication use for the past 24 hours before the interview. The overall number of participants who took antidepressants was small; the width of the confidence interval for the use of antidepressants is noteworthy. Finally, the study subjects consisted of a group of survivors.

Nevertheless, we were able to capitalize on a fortuitous circumstance. New-generation antidepressants were introduced and became widely prescribed during the 10 years of the study (2). In consequence, we have been able to examine how characteristics of users have changed with the availability of these new medications.

We found that the basic characteristics of users (white race, prior use of antidepressants, negative symptoms indicative of depression) persisted across the two intervals and that the discrepancy in use between whites and African Americans appears to be increasing. We previously reported that African Americans in North Carolina were less likely to use over-the-counter medications and total medications, with the greatest differences found for psychotropic drugs and nutritional supplements (16). These medications perhaps are viewed by both doctors and their patients as less imperative to be prescribed than, for example, medications for hypertension (for which use does not vary by race). One may speculate that the dramatic increase in use of antidepressants reflects physicians’ greater comfort in prescribing these medications for patients who are less critically ill. If so, then the increasing disparity in the use of antidepressants by race suggests that the need for antidepressants among African Americans may be viewed as less critical to their health care than their need for other medications. Given that the frequency of depression does not vary by race (14), then community-dwelling older African Americans may be significantly undertreated.

Other characteristics of the user base have broadened to include physical health, cognitive status, and a broader array of depressive symptoms. Although the indications for use of the new-generation antidepressant agents are widening, these findings suggest that these agents are being use for an even wider range of symptoms, perhaps for behavioral control of dementing disorders and mild psychiatric symptoms associated with physical illness. In addition, these agents are clearly being used for depressive symptoms that do not meet the criteria for major depressive disorder, given the frequency of use compared to the frequency of major depressive disorder in late life among community-dwelling older adults, which rarely exceeds 5% in survey data (26, 27).

|

|

|

|

Received May 25, 2004; revision received Aug. 11, 2004; accepted Aug. 20, 2004. From the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Department of Biostatistics and Bioinformatics, Center for the Study of Aging and Human Development, Duke University Medical Center; and the Geriatric Education, Research, and Clinical Center, Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Durham, N.C. Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. Blazer, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Duke University Medical Center, Box 3003, Durham, NC 27710; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by grant 5R01-AG-20614 from the National Institute on Aging and grant MH-066380 from the National Institute of Mental Health. Additional support was provided by grant 5P60 AG-11268 from the National Institute on Aging to the Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center, Duke University. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

1. Glaser M: Annual Rx survey hats off. Drug Topics 1995; 139:43–48Google Scholar

2. Pincus H, Tanielin S, Marcus S, Olfson M, Zarin D, Thompson J, Magno Zito J: Prescribing trends in psychotropic medications: primary care, psychiatry, and other medical specialties. JAMA 1998; 279:526–531Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Helgason T, Tomasson H, Zoega T: Antidepressants and public health in Iceland. Br J Psychiatry 2004; 184:157–162Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. IMS Health: IMS HEALTH Reports 10 Percent Growth in 2000 Audited Global Total Pharmaceutical Sales to $317.2 Billion. http://www.imshealth.com/ims/portal/front/articleC/0,27777,6025_3665_1003594,00.htmlGoogle Scholar

5. Blazer DG, Hybels CF, Simonsick EM, Hanlon JT: Marked differences in antidepressant use by race in an elderly community sample: 1986–1996. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:1089–1094Link, Google Scholar

6. Radloff LS: The CES-D Scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Journal of Applied Psychological Measurement 1977; 1:385–401Crossref, Google Scholar

7. Akiskal H: Mood disorders: clinical features, in Kaplan and Sadock’s Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry, 7th ed. Edited by Sadock BJ, Sadock VA. Philadelphia, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2000, pp 1338–1376Google Scholar

8. Blazer DG: Impact of late-life depression on the social network. Am J Psychiatry 1983; 140:162–166Link, Google Scholar

9. Weissman M, Sholamskas D, Pottenger M, Prusoff B, Locke B: Assessing depressive symptoms in five psychiatric populations: a validation study. Am J Epidemiol 1977; 106:203–214Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Cornoni-Huntley J, Blazer D, Lafferty M, Everett D, Brock D, Farmer M: Established Populations for Epidemiologic Studies of the Elderly: Resource Data Book. Bethesda, Md, National Institutes of Health, 1990Google Scholar

11. Blazer D, Burchett B, Service C, George LK: The association of age and depression among the elderly: an epidemiologic exploration. J Gerontol 1991; 46:M210-M215Google Scholar

12. Fillenbaum GG, Leiss JK, Pieper CF, Cohen HJ: Developing a summary measure of medical status. Aging (Milano) 1998; 10:395–400Medline, Google Scholar

13. Pfeiffer E: A short portable mental status questionnaire for the assessment of organic brain deficit in elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc 1975; 23:433–441Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Blazer D, Landerman L, Hays J, Simonsick E, Saunders W: Symptoms of depression among community-dwelling elderly African-American and white older adults. Psychol Med 1998; 28:1311–1320Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Blazer DG, Hybels CF: What symptoms of depression predict mortality in community dwelling elders? J Am Geriatr Soc 2004; 52:2052–2056Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Hanlon JT, Fillenbaum GG, Burchett B, Wall WE Jr, Service C, Blazer DG, George LK: Drug-use patterns among black and nonblack community-dwelling elderly. Ann Pharmacother 1992; 26:679–685Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Fillenbaum G, Hanlon J, Corder E, Ziqubu-Page T, Wall W, Brock D: Prescription and nonprescription drug use among black and white community-residing elderly. Am J Public Health 1993; 83:1577–1582Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Helling D, Lemke J, Semla T, Wallace R, Lipson D, Cornoni-Huntley J: Medication use characteristics in the elderly: the Iowa 65+ Rural Health Study. J Am Geriatr Soc 1987; 35:4–12Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. DeVito C, Aldridge G, Wilson A, Vidas J, Goldberg T, Dickson W: Framework and development of a comprehensive drug product coding system. Contemp Pharm Pract 1979; 2:62–65Medline, Google Scholar

20. SAS/STAT User’s Guide, version 8.1. Cary, NC, SAS Institute, 2000Google Scholar

21. Kleinbaum D, Klein M: Logistic Regression: A Self-Learning Text, 2nd ed. New York, Springer, 2002Google Scholar

22. Li Y, Meyer J, Thornby J: Longitudinal follow-up of depressive symptoms among normal versus cognitively impaired elderly. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2001; 16:718–727Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Lyketsos C, Baker L, Warren A, Steele C, Brandt J, Steinberg M: Major and minor depression in Alzheimer’s disease: prevalence and impact. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1997; 9:556–561Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Williams J, Mulrow C, Chiquette E, Noel P, Aguilar C, Cornell J: A systematic review of newer pharmacotherapies for depression in adults: evidence report summary. Ann Intern Med 2000; 132:743–756Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Hybels C, Blazer D, Pieper C: Toward a threshold for subthreshold depression: an analysis of correlates of depression by severity of symptoms using data from an elderly community survey. Gerontologist 2001; 41:357–365Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Weissman M, Bruce M, Leaf P, Florio L, Holzer C III: Affective disorders, in Psychiatric Disorders in America: The Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study. Edited by Robins L, Regier D. New York, Free Press, pp 53–80Google Scholar

27. Beekman A, Deeg D, van Tilberg T, Smit J, Hooijer C, van Tilberg W: Major and minor depression in later life: a study of prevalence and risk factors. J Affect Disord 1995; 36:65–75Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar