Epidemiology of and Risk Factors for Psychosis of Alzheimer’s Disease: A Review of 55 Studies Published From 1990 to 2003

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The authors reviewed studies published between 1990 and 2003 that reported the prevalence, incidence, and persistence of, as well as the risk factors associated with, psychosis of Alzheimer’s disease. METHOD: PubMed and PsycINFO databases were searched by using the terms “psychosis and Alzheimer disease” and “psychosis and dementia.” Empirical investigations presenting quantitative data on the epidemiology of and/or risk factors for psychotic symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease were included in the review. A total of 55 studies, including a total of 9,749 subjects, met the inclusion criteria. RESULTS: Psychosis was reported in 41% of patients with Alzheimer’s disease, including delusions in 36% and hallucinations in 18%. The incidence of psychosis increased progressively over the first 3 years of observation, after which the incidence seemed to plateau. Psychotic symptoms tended to last for several months but became less prominent after 1 year. African American or black ethnicity and more severe cognitive impairment were associated with a higher rate of psychosis. Psychosis was also associated with more rapid cognitive decline. Some studies found a significant association between psychosis and age, age at onset of Alzheimer’s disease, and illness duration. Gender, education, and family history of dementia or psychiatric illness showed weak or inconsistent relationships with psychosis. CONCLUSIONS: Psychotic symptoms are common and persistent in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Improved methods have advanced the understanding of psychosis in Alzheimer’s disease, although continued research, particularly longitudinal studies, may unveil biological and clinical associations that will inform treatments for these problematic psychological disturbances.

From the time of Alzheimer’s first description of psychotic symptoms in a patient with Alzheimer’s disease in 1907, psychosis has been recognized as a major clinical syndrome in this illness. The consequences of psychotic symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease may be painful and costly for the affected individuals, those who care for them, and society at large. Psychotic symptoms have been linked to greater caregiver distress (1–3) and have been found to be a significant predictor of functional decline and institutionalization (4–7). Compared to patients with Alzheimer’s disease without psychosis, those with Alzheimer’s disease and psychotic symptoms are also more likely to have worse general health (8) as well as a greater incidence of other psychiatric and behavioral disturbances (9–11). Psychotic patients tend to have more frequent and problematic behaviors, including agitation (12–14), episodes of verbal and physical aggression (10, 15–18), and anxiety (11).

Reviews completed before the early 1990s found that psychotic symptoms were common in dementia, including Alzheimer’s disease (19–23). In their review of 21 studies, for example, Wragg and Jeste (23) found that approximately one-third of all patients with Alzheimer’s disease had delusions at some point during their illness, 28% had hallucinations, and nearly 35% had other psychotic symptoms that were difficult to categorize. Overall, however, the reviewed studies were compromised by sampling deficiencies and methodological problems. Wragg and Jeste’s review included studies with as few as nine subjects. Moreover, only five of the 21 studies had a sample size larger than 100 subjects. Other methodological problems included the use of unreliable or nonvalidated diagnostic criteria for Alzheimer’s disease. Consequently, samples included individuals with various types of dementias, and thus generalizability was limited, and findings as they related to Alzheimer’s disease specifically were obscured. Imprecise operational definitions of psychosis (24) and utilization of assessment methods with questionable reliability and validity also undermined these investigations. Moreover, all of the studies published before 1990 were cross-sectional or descriptive and thus did not provide data on the incidence or course (e.g., persistence) of symptoms.

Since the early 1990s, research on psychosis of Alzheimer’s disease has advanced considerably. There have been improvements in the development of diagnostic criteria for Alzheimer’s disease and for psychosis of Alzheimer’s disease (25) and the development of more reliable measures of psychotic symptoms, including the Behaviorial Pathology in Alzheimer’s Disease Rating Scale (26) and the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (27). Larger sample sizes have become available because of increased awareness of the disease and the establishment of Alzheimer’s disease centers. Longitudinal data from these centers have become available, and more investigators have undertaken prospective studies on this topic.

We reviewed studies published from 1990 through 2003 that investigated psychosis of Alzheimer’s disease with the aim of providing a systematic overview of the current state of knowledge in this area. In so doing, we employed more stringent inclusion criteria than were applied in reviews conducted before the early 1990s. In this article, we summarize findings on the epidemiology of psychotic symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease. Delusions and hallucinations are also reviewed separately, and we include findings on other uncategorized psychotic symptoms. In addition, we examine the literature on potential risk factors for psychosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Implications of the findings for clinical practice and for future research are discussed.

Method

Computerized searches using PubMed and PsycINFO databases were performed for English-language articles published between 1990 and the end of 2003 with the keywords “psychosis and Alzheimer disease” and “psychosis and dementia.” Additional articles were identified by using the “related articles” function in PubMed and by cross-referencing identified articles. Only empirical investigations reporting data on psychotic symptoms in patients with Alzheimer’s disease were selected. If a given study included subjects with dementias other than Alzheimer’s disease (e.g., vascular dementia or mixed dementia), sufficient data on the Alzheimer’s disease group itself (e.g., number of subjects and a prevalence rate of psychotic symptoms) must have been provided. In addition, the study design, study setting, some description of the method of diagnosing Alzheimer’s disease (e.g., National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association criteria), and description of how psychotic symptoms were measured or defined must have been clearly stated. Target symptoms that could not be well categorized as delusions or hallucinations were considered “other psychotic symptoms.” Using these methods, we identified 55 articles for review.

Results

Sample Size and Subject Characteristics

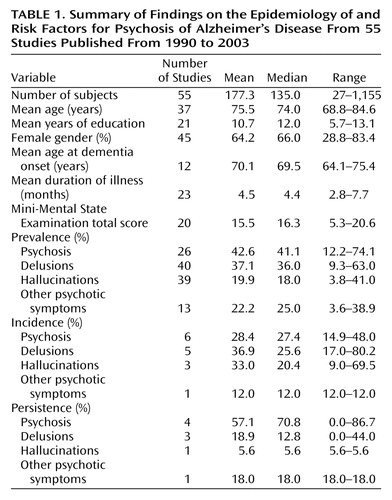

The mean sample size in the 55 studies reviewed (Table 1) was 177 subjects (median=135; range 27 to 1,155). These findings represent an increase in sample sizes from those in the studies of psychosis in Alzheimer’s disease prior to 1990 that were included in a previous review (23). In that review, the largest sample size among 21 studies was merely 175 subjects, and the median sample size was 33. In the current review, the mean age of subjects with Alzheimer’s disease was 75.5 years (median=74.0, range=69–85), and the mean level of education was 10.7 years (median=12.0, range=6–13). Inclusion of education data was not possible for some studies because of the use of alternative scales of measurement (e.g., less than high school versus high school). Nearly two-thirds of the total subject sample were women (mean=64.2%), although considerable variability in gender distribution was noted across studies, with the proportion of women ranging from 28.8% to 83.4%. In general, subjects included in the studies tended to have mild or moderate cognitive impairment, as reflected by a mean Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) (28) score of 15.5 (median=16.3; range 5–21), although there was considerable variability in this regard across studies as well. Relatively few studies provided data on age at onset or the mean duration of illness. These variables may be considered unreliable estimates because they are based on a patient’s or informant’s retrospective memory and/or perceptions.

Study Design and Setting

Although a majority of the reports (63.6%) were cross-sectional (8, 10, 12, 17, 29–60), 34.5% of the studies provided longitudinal data (9, 13, 16, 63–78). The primary settings for 72.7% of the studies were outpatient clinics, Alzheimer’s disease clinical centers, or Alzheimer’s disease research centers (8, 10, 12, 13, 16, 17, 29–32, 34–39, 43, 44, 48–50, 52, 53, 55, 57–74); relatively few studies included samples of inpatients (33, 41, 45–47, 56, 75) or a combination of inpatients and outpatients (9, 42). Even fewer reports (51, 54) included community-based samples, which are often more difficult to obtain. The setting was not clear in one investigation (76).

Diagnosis and Measurement

The National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association criteria (77) were used most commonly for diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease (8, 10, 12, 16, 31–34, 36, 40–44, 48, 50–55, 57, 61–63, 65, 66, 71–75). Both those criteria and the DSM criteria were used together in several studies (9, 13, 17, 29, 30, 35, 37, 45–47, 50, 59, 63, 64, 67, 69). Autopsy results, specifically those that utilized criteria of the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (78), were used infrequently.

Numerous measures or tools were used alone or in combination to assess psychotic symptoms. Informal or semistructured interviews of patients and/or their caregivers (such as the National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule [79], the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders [80], and the Initial Evaluation Form [81]) were utilized most frequently (15 studies), with an additional six studies incorporating other measures in addition to interviews. The Behavioral Pathology in Alzheimer’s Disease Rating Scale and the Neuropsychiatric Inventory, or both, were also used frequently.

Results

Epidemiology

Prevalence

The median prevalence of psychotic symptoms (delusions or hallucinations) in patients with Alzheimer’s disease was 41.1% (range=12.2%–74.1%). The median prevalence of delusions was 36% (range=9.3%–63%). Delusions of theft were the most common type of delusions reported (50.9% of studies). Hallucinations occurred less frequently, with a median prevalence of 18% (range=4%–41%). Visual hallucinations were more prevalent than auditory hallucinations (median=18.7% and 9.2%, respectively). Between 7.8% and 20.8% of subjects (median=13%) experienced both hallucinations and delusions. Psychotic symptoms not categorized as delusions or hallucinations were reported by 3.6% to 38.9% of patients with Alzheimer’s disease (median=25.6%). Most often, this category comprised misidentifications (frequently considered to be a type of delusion, although it may be a separate phenomenon). Prevalence data are summarized in Table 1.

Prevalence is affected by several factors, including the study setting and study design. A higher prevalence of psychotic symptoms tended to occur in inpatient settings (e.g., acute care hospitals, nursing homes, neurobehavioral units) (31.2% to 74.1%) (33, 40, 41, 45–47, 56, 75), whereas lower rates (12.2% to 65.2%) were noted in patients referred to outpatient memory or research clinics (8, 10, 12, 13, 16, 17, 29–32, 34–38, 43, 44, 48–50, 52, 53, 55, 57–61, 63–70, 72–74). Two studies included a community sample (51, 54), and one reported that 26.9% of the subjects experienced psychosis (51). Delusions among inpatients were present in 44.4% to 62.9% and hallucinations were present in 5.7% to 34%. In outpatient samples, 9.3% to 63% of subjects experienced delusions, and 3.8% to 41% had hallucinations. In the two studies of community-dwelling subjects, 21.8% and 22.7% had delusions, and 12.8% and 13.1% had hallucinations.

Incidence

The incidence of psychosis of Alzheimer’s disease refers to the percentage of individuals with Alzheimer’s disease who are initially not psychotic and who develop one or more psychotic symptoms by a specified end-point. No studies before 1990 reported data on incidence. In studies conducted since 1990, however, seven studies (13, 61, 63, 64, 66, 69, 73) reported data on incidence over observation periods ranging from 1 to 5 years. Paulsen et al. (69) reported a 1-year incidence of 20%. Levy and colleagues (13) reported a comparable incidence of 25% after 1 year. Over a 2-year period, Paulsen and colleagues (69) reported an incidence of 36.1%, and in the study by Caligiuri et al. (63) of neuromotor abnormalities and risk for psychosis, 32.5% of subjects developed psychotic symptoms over the course of 2 years. The latter rates are likely comparable because the samples from the two studies overlapped to some extent, given that subjects in both studies were drawn from the same group of individuals enrolled in longitudinal studies at the Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center in San Diego. Delusions and hallucinations both seem to develop more readily within a 1-year to 2-year span, although these data are limited by the small number of studies addressing delusions and hallucinations specifically over more than two assessment points (60, 65). Incidence seemed to plateau after 3 years, as there was little difference between 3-year (49.5%) and 4-year (51.3%) cumulative rates for psychosis in the study by Paulsen et al. (69). In the study by Chen and colleagues (64), 29.7% of the subjects developed psychosis over an average of 5 years of follow-up. However, the authors pointed out that subjects were not evaluated the same number of times or at the same time points. The 14.9% incidence reported by Sweet and associates (73) was difficult to compare to the findings of other studies because the length of follow-up was not specified.

Persistence

Persistence of psychosis of Alzheimer’s disease refers to whether an individual experiences a symptom at two or more consecutive evaluations. Again, comparison of rates across studies is limited because variable follow-up periods were used by different researchers. In one study, subjects were evaluated every 3 months over 1 year, and 57% had psychotic symptoms on at least two occasions (13). In another study, a similarly high persistence of psychosis was found for individuals evaluated at baseline and 1 year later: 44% for delusions, 26% for visual hallucinations, and 45% for auditory hallucinations (61). Psychotic symptoms rarely seemed to persist after several months, however. Haupt et al. (66) reported that after 2 years, psychotic symptoms did not persist in any of 21 subjects who had delusions or in any of 11 subjects who had hallucinations at baseline. The results may have been affected by the small number of patients manifesting psychotic symptoms. Furthermore, the authors assessed symptoms at 1 and 2 years but reported persistence on the basis of the presence of a symptom at both time points. A low persistence rate over a 2-year period was also found by Devanand and colleagues (9), who reported that delusions persisted in only 12.8% of 180 subjects and hallucinations in only 5.6%. Rosen et al. (70) and Zubenko et al. (76) considered a symptom to be persistent if it was present on any two consecutive annual evaluations conducted over the course of the study (on average, 2 and 5 years, respectively). Using this definition, these authors reported that 86.7% and 84.6%, respectively, of the same subject sample had persistent psychotic symptoms.

Risk Factors

Seven studies examined the relationship between African American or black ethnicity and psychosis. Five found a positive association (8, 16, 31, 36, 52), and two found no relationship (9, 32). Bassiony and colleagues (31) reported that African Americans were significantly more likely to have hallucinations than Caucasians; the investigators did not report on other psychotic symptoms. Lopez et al. (52) reported that African Americans in the moderate to severe stages of Alzheimer’s disease had significantly more psychotic symptoms than Caucasians in the same stages; the relationship between ethnicity and psychotic symptoms was not significant in mild stages, however. No studies reported associations with any other ethnic groups. Associations between risk factors and psychosis are summarized in Table 2.

Severity of cognitive impairment (assessed with the MMSE or a similar global cognitive measure) showed a significant positive association with the presence of psychosis in individuals with Alzheimer’s disease in 20 studies (8, 9, 12, 13, 31, 32, 34, 36, 37, 40, 44, 45, 48, 52, 57, 65, 67–69, 74) and no association in 10 studies (10, 33, 39, 42, 47, 50, 51, 58, 62, 70). Overall, the prevalence of psychosis in general increased as cognitive impairment became more severe. Delusions tended to initially become more prevalent as cognitive functioning worsened but then decreased again as cognitive impairment became more severe in later stages of the illness. Hallucinations, like general psychotic symptoms, also increased in prevalence as cognitive impairment became more severe. When subjects were categorized as mildly, moderately, or severely cognitively impaired on the basis of MMSE scores (28), a similar pattern was observed. The median prevalence of psychosis was 25.5% (range=3.1%–50%) in mildly impaired individuals (MMSE scores 21–25), 37% (range=18.8%–56%) in those with moderate cognitive impairment (MMSE scores 20–11), and 49% (range=21.9%–79%) in severely impaired subjects (MMSE score 10 or below). Delusions were reported in a median of 23.5% (range=11%–50%) of mildly impaired individuals, 46% (range=13%–67%) of those with moderate cognitive impairment, and 33.3% (range=23%–57%) of severely impaired subjects. The median prevalence of hallucinations among those with mild cognitive impairment was 11.4% (range=9%–33%) and increased to 19% in those with moderate cognitive impairment (range=13%–48%) and to 28% (range=16%–44%) in severely impaired patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Other psychotic symptoms occurred in 5.9% and 16.7% of mildly impaired subjects (as reported in two studies), in 43.5% of moderately impaired individuals, and in 41.7% of those with severe cognitive impairment (one study). Overall, a statistical examination of the mean prevalence figures for psychotic symptoms and cognitive severity level revealed a significant difference only between the mean prevalence of hallucinations in mildly and moderately impaired individuals, with hallucinations being more prevalent in the moderately impaired than in the mildly impaired subjects. There were no other significant differences in mean prevalence of symptoms at any other levels of cognitive impairment.

Education, gender, and family history of dementia or psychiatric disorder were weakly associated with increased risk for psychosis in the majority of reviewed studies. A majority of studies (76.5%) found that education level was not correlated with the presence of psychotic symptoms (10, 16, 31, 36, 37, 44, 45, 47, 48, 50, 51, 56, 69). In contrast, education level was positively associated with delusions in one study (33) and negatively associated with psychosis in three (8, 32, 52). Gender was not associated with psychosis in 17 studies presenting these data (9, 10, 16, 31, 32, 36, 37, 44, 47, 48, 50, 55, 56, 68–70, 76), but it was associated with psychosis in seven. Of those seven, four found that women were at greater risk for psychotic symptoms (45, 51, 63, 65) and three found that men had a higher risk for psychosis (39, 42, 62). Of seven studies that investigated the association of family history of dementia and/or other psychiatric disorders and psychosis in Alzheimer’s disease (8, 10, 12, 31, 37, 48, 56), none found a positive relationship. However, lack of knowledge and diagnostic inaccuracy in diagnosis among family members could have obscured such an association.

The relationships between psychosis and patients’ age, age at onset of Alzheimer’s disease, and duration of Alzheimer’s disease were generally equivocal. Older age was correlated with psychotic symptoms (delusions, hallucinations, or both) in 12 of 25 studies (8, 13, 17, 32, 36, 37, 40, 45, 47, 50, 55, 56) and was not associated with psychosis in the remaining 13 investigations (9, 10, 31, 42, 43, 48, 57, 59, 62, 69, 70, 75, 76). In 12 studies reporting on the relationship between age at onset of Alzheimer’s disease and psychotic symptoms, seven studies found no relationship (12, 16, 42, 47, 51, 68, 76), four found that the later the age at onset of Alzheimer’s disease, the more likely the individual was to experience psychosis (40, 45, 56, 75), and only one found that an earlier age at onset was associated with psychosis (62). Nine of 17 studies found no relationship between duration of Alzheimer’s disease and the occurrence of psychotic symptoms (36, 47, 51, 55, 56, 58, 68, 71, 76). The other eight studies, however, found that a longer duration of Alzheimer’s disease was correlated with the occurrence of psychosis (12, 17, 31, 32, 34, 37, 39, 45).

Other Associations

Psychotic symptoms were significantly associated with more rapid cognitive decline over time in all nine studies that examined this relationship (13, 37, 40, 58, 62, 69–71, 74), supporting the notion that psychosis may denote a subset of patients with Alzheimer’s disease with a more aggressive course of the disease (see references 13, 69, 70). It is interesting to note that only two of these studies examined the relationship between the rate of cognitive decline and hallucinations or delusions separately, and each found that hallucinations, but not delusions, were significantly associated with more rapid cognitive decline (62, 74).

Discussion

Our review of 55 studies of psychosis in possible or probable Alzheimer’s disease revealed that a sizable proportion (median 41%) of individuals with the disease experience psychotic symptoms at some time during the course of their illness. Delusions occurred more frequently (median=36%) than hallucinations (median=18%). Other psychotic symptoms not categorized as delusions or hallucinations occurred in 25% of individuals. The incidence of psychotic symptoms seemed to increase with increasing follow-up intervals over the first 3 years. Psychotic symptoms tended to be reported in a majority of patients at least over a period of several months but often were not observed beyond 1 or 2 years. African American or black ethnicity and greater degree of cognitive impairment were strongly associated with a higher rate of psychosis. Psychosis was also associated with a faster rate of cognitive decline. Age, age at onset of Alzheimer’s disease, and duration of Alzheimer’s disease were associated with psychosis in approximately one-half of studies. Education, gender, and family history of dementia or psychiatric illness showed a weak or inconsistent relationship with psychosis in patients with Alzheimer’s disease.

The prevalence rate of psychosis in patients with Alzheimer’s disease found in our review was 41%. The median rate for delusions was 36%, which is comparable to the median rate of 33.5% reported in one of the only review studies of psychosis in Alzheimer’s disease published before the early 1990s (23). The rate of hallucinations found in the present review (18%) represents a decrease from the 28% reported by Wragg and Jeste (23). The fact that prevalence remains high in light of pharmacologic treatment may reflect increased awareness that these disturbances are consequences of Alzheimer’s disease, improved detection, or the use of better criteria and rating scales that allow for psychotic symptoms to be diagnosed with greater accuracy. As an increasing number of patients with Alzheimer’s disease are treated with cholinesterase inhibitors over the coming years, we might expect that the prevalence and incidence of psychosis would decrease, although findings for the efficacy of these drugs in reducing psychotic symptoms specifically have been mixed (see references 13, 82, 83).

The fact that psychosis is persistent over a short interval of a few months may reflect the reasonable amount of time it takes to begin typical treatment for psychosis and to observe amelioration of symptoms. To assess the true persistence of symptoms, subjects would have to be enrolled in a placebo-controlled study in which some psychotic patients did not receive the typical treatment for symptoms. In the studies that were reviewed, it was more the exception than the rule that subjects would be excluded if they were taking an antipsychotic drug or cholinesterase inhibitor or that a drug washout period would be invoked. Furthermore, there were no means of determining whether the patients who were taking these drugs were being treated optimally, and the extent to which psychotic symptoms persist despite antipsychotic treatment is not known. Therefore, persistence values may reflect the experience of psychosis given current treatments rather than the true persistent nature of psychotic symptoms.

Few equivocal associations with psychosis emerged from the reviewed studies. The association between African American or black ethnicity and psychosis is intriguing, although it is also limited by the fact that only Caucasian samples are available for comparison. Issues of acculturation and genetic influences are yet to be adequately examined, highlighting an area in need of exploration. Cognitive impairment and the rate of cognitive decline were also found to be strongly associated with psychotic symptoms.

The findings of the present review suggest that psychosis represents a developmental feature marking the progression of Alzheimer’s disease or that it represents a distinct disease subtype marked by psychotic symptoms and a particularly rapid disease course. The fact that delusions, specifically, seemed most prevalent in patients with moderate cognitive impairment supports the hypothesis that a certain amount of neuronal integrity must be present for delusions to occur (see references 48, 84). Conclusions are limited, however, by a general failure to include severely cognitively impaired subjects in these studies. In addition, the association between psychosis and cognitive impairment and between psychosis and rate of cognitive decline may be influenced by medications, including antipsychotics and cholinesterase inhibitors, the former of which is recommended as a first-line treatment for dementia patients with delusions (85). Yet, a majority of the studies reviewed did not account for the potential effects of medication on cognition and simply reported that these effects were a possible limitation to their findings. A number of studies altogether failed to report what, if any, medications the subjects were taking. The importance of considering medication effects is illustrated in studies of antipsychotic use and cognition. The use of two atypical antipsychotics (clozapine and risperidone) in cognitively impaired patients was reviewed by Jeste et al. (86) and Gladsjo et al. (87). Jeste and colleagues found that the effects of clozapine on cognition were somewhat conflicting, which they posited was due, at least in part, to the strong anticholinergic activity of clozapine, which is likely to confound or diminish any enhancement of cognitive functioning. Berman and colleagues (88, 89) reported significant increases in MMSE scores in patients with schizophrenia or mild dementia treated with risperidone. Moreover, cholinesterase inhibitors have been shown to improve cognitive symptoms or temporarily reduce the rate of cognitive decline (90). Certainly, future studies should examine the potential influence of medication use, not only to examine any potential effects, positive or negative, on cognitive functioning but also to elucidate underlying biological mechanisms of psychosis in dementia. Furthermore, difficulties in diagnosing patients with Lewy body dementia may have led to their inadvertent inclusion in studies of patients with Alzheimer’s disease, thereby affecting the association between some psychotic symptoms and rate of cognitive decline, given that psychotic symptoms, and hallucinations in particular, may occur in nearly one-half of those with Lewy body dementia (30, 91).

For many variables that were found not to be associated with psychosis, including age, age at onset, and duration of illness, small standard deviations likely affected the detection of associations. In the case of age and age at onset, few individuals who were younger than age 55 years or who had an early age at onset (age 55 years or younger) were included in these studies. Similarly, the range and standard deviation for illness duration were restricted (range=2.8–7.7 years, SD=1.33 years), thus limiting the potential to detect a positive association. In addition, many authors noted that age at onset of Alzheimer’s disease was inherently difficult to determine, because it was often an estimate that relied on the failing memory of those with Alzheimer’s disease or the recall and dating by others of behaviors that occurred several years earlier.

The results of this review are also limited by problems in assessing psychosis. Despite more regular use of accepted diagnostic criteria, some researchers continue to use diagnostic criteria that are nonspecific to Alzheimer’s disease (e.g., DSM-III or DSM-IV criteria). Even when accepted criteria are utilized, inconsistencies in interpreting those criteria are evident. Presumably, the rates reported herein may underestimate the prevalence of delusions and hallucinations specifically, as evidenced by the fact that from 3.6% to 38.9% of psychotic symptoms remained uncategorized and were labeled “other psychotic symptoms.” Conversely, as suggested by Devanand and colleagues (24), the lack of clarity may result in an overestimation of prevalence rates for symptoms such as delusions, as some symptoms are classified as delusions when they would otherwise be better classified as other psychiatric symptoms or as behavioral problems of Alzheimer’s disease. Clarity regarding the definition of psychosis and the categorization of symptoms such as misidentifications will be necessary to produce data that can be better compared across studies.

Overall, the present review reflects improvements in sampling, study design, diagnosis, and assessment, compared to reviews conducted before the early 1990s. Subject samples were larger, providing a more accurate picture of the nature and frequency of psychosis. More studies were prospective in nature and thus used methods designed to answer a directed research question. Longitudinal data were more readily available, providing information on incidence that had not previously been reported and other insights into how psychotic symptoms affect the course of Alzheimer’s disease over time. More reliable assessment tools have also come into use over the past decade with the advent of measurements such as the Neuropsychiatric Inventory and Behaviorial Pathology in Alzheimer’s Disease Rating Scale and the use of structured clinical interviews, as opposed to the previously employed methods of chart review and behavioral observation. However, future studies should continue to address the remaining shortcomings of the past 15 years. Research should use longitudinal designs to advance our understanding of the incidence and persistence of psychosis. Future studies should also develop or utilize appropriate diagnostic criteria and rating scales for psychosis in the Alzheimer’s disease population. By taking into account medication use (such as antipsychotics and anticholinergics) among subjects included in these studies, we may also learn about the relative benefits of various pharmacological agents in treating psychosis as well as the mechanisms underlying the occurrence of psychotic symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease and other illnesses.

Conclusions

Research since the early 1990s shows that psychotic symptoms affect a sizable proportion of individuals with Alzheimer’s disease. The incidence of psychosis in any sample of patients typically continues to climb during the first 3 years of observation and may persist for several months, pointing to the necessity for early detection and treatment. With recognition of how prominent and devastating psychotic symptoms may be, it becomes increasingly clear that research should continue to focus on the epidemiology of and risk factors for psychosis of Alzheimer’s disease. As Alzheimer’s disease affects a growing number of individuals over time, so too will psychosis as a syndrome. Systematic delineation of the epidemiology of and risk factors for psychosis in Alzheimer’s disease may clarify the biological underpinnings of these symptoms and direct indications for early interventions, facilitate patient management, reduce caregiver burden, improve patients’ quality of life, and open the door to discovering the nature of psychosis in other diseases.

|

|

Received Nov. 29, 2004; revision received Feb. 1, 2005; accepted Feb. 22, 2005. From the Department of Psychiatry, University of California, San Diego; and the Veterans Affairs San Diego Healthcare System, San Diego. Address correspondence to Dr. Jeste, Department of Psychiatry, University of California, San Diego, VA San Diego Healthcare System, 9500 Gilman Dr., Mail Code 0603V, La Jolla, CA 92093-0603; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported in part by NIMH grants MH-66248 and MH-59101 and by the Department of Veterans Affairs.

1. Bedard M, Molloy DW, Pedlar D, Lever JA, Stones MJ: Associations between dysfunctional behaviors, gender, and burden in spousal caregivers of cognitively impaired adults. Int Psychogeriatr 1997; 9:277–290Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Donaldson C, Tarrier N, Burns A: Determinants of carer stress in Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1998; 13:248–256Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Kaufer DI, Cummings JL, Christine D, Bray T, Castellon S, Masterman D, MacMillan A, Katchel P, DeKosky ST: Assessing the impact of neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease: the Neuropsychiatry Inventory Caregiver Distress Scale. J Am Geriatr Soc 1998; 46:210–215Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Cummings JL, Diaz C, Levy ML, Binetti G, Litvan II: Neuropsychiatric syndromes in neurodegenerative diseases: frequency and significance. Semin Clin Neuropsychiatry 1996; 1:241–247Medline, Google Scholar

5. Lopez OL, Wisniewski SR, Becker JT, Boller F, DeKosky ST: Psychiatric medication and abnormal behavior as predictors of progression in probable Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol 1999; 56:1266–1272Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Magni E, Binetti G, Bianchetti A, Trabucchi M: Risk of mortality and institutionalization in demented patients with delusions. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 1996; 9:123–126Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Rabins PV, Mace NL, Lucas MJ: The impact of dementia on the family. JAMA 1982; 248:333–335Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Bassiony MM, Steinberg MS, Warren A, Rosenblatt A, Baker AS, Lyketsos CG: Delusions and hallucinations in Alzheimer’s disease: prevalence and clinical correlates. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2000; 15:99–107Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Devanand DP, Jacobs DM, Tang MX, Del Castillo-Casteneda C, Sano M, Marder K, Bell K, Bylsma FW, Brandt J, Albert M, Stern Y: The course of psychopathologic features in mild to moderate Alzheimer disease. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1997; 54:257–263Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Kotrla KJ, Chacko RC, Harper RG, Doody R: Clinical variables associated with psychosis in Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:1377–1379Link, Google Scholar

11. Schneider LS, Katz IR, Park S, Napolitano J, Martinez RA, Azen SP: Psychosis of Alzheimer disease: validity of the construct and response to risperidone. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2003; 11:414–425Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Gilley DW, Whalen ME, Wilson RS, Bennett DA: Hallucinations and associated factors in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1991; 3:371–376Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Levy ML, Cummings JL, Fairbanks LA, Bravi D, Calvani M, Carta A: Longitudinal assessment of symptoms of depression, agitation, and psychosis in 181 patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:1438–1443Link, Google Scholar

14. Tractenberg RE, Weiner MF, Patterson MB, Teri L, Thal LJ: Comorbidity of psychopathological domains in community-dwelling persons with Alzheimer’s disease. J Geriatr Psychiatry 2003; 16:94–99Crossref, Google Scholar

15. Aarsland D, Cummings JL, Yener G, Miller B: Relationship of aggressive behavior to other neuropsychiatric symptoms in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:243–247Link, Google Scholar

16. Deutsch LH, Bylsma FW, Rovner BW, Steele C, Folstein MF: Psychosis and physical aggression in probable Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Psychiatry 1991; 148:1159–1163Link, Google Scholar

17. Doody RS, Massman P, Mahurin R, Law S: Positive and negative neuropsychiatric features in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1995; 7:54–60Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Lopez OL, Becker JT, Brenner RP, Rosen J, Bajulaiye OI, Reynolds CF: Alzheimer’s disease with delusions and hallucinations: neuropsychological and electroencephalographic correlates. Neurology 1991; 41:906–912Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Burns A: Psychiatric phenomena in dementia of the Alzheimer type. Int Psychogeriatr 1992; 4:43–54Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Devanand DP, Sackeim HA, Mayeux R: Psychosis, behavioral disturbance, and the use of neuroleptics in dementia. Compr Psychiatry 1988; 29:387–401Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Flint AJ: Delusions in dementia: a review. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1991; 3:121–130Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Wragg RE, Jeste DV: Neuroleptics and alternative treatments: management of behavioral symptoms and psychosis in Alzheimer’s disease and related conditions. Psychiatr Clin North Am 1988; 11:195–214Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Wragg RE, Jeste DV: Overview of depression and psychosis in Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Psychiatry 1989; 146:577–587Link, Google Scholar

24. Devanand DP, Miller L, Richards M, Marder K, Bell K, Mayeux R, Stern Y: The Columbia University Scale for psychopathology in Alzheimer’s disease. Arch Neurol 1992; 49:371–376Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Jeste DV, Finkel SI: Psychosis of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias: diagnostic criteria for a distinct syndrome. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2000; 8:29–34Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Reisberg B, Borenstein J, Salob SP, Ferris S, Franssen E, Georgotas A: Behavioral symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease: phenomenology and treatment. J Clin Psychiatry 1987; 48:9–15Medline, Google Scholar

27. Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray K, Rosenberg-Thompson S, Carusi DA, Gornbein J: The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology 1994; 44:2308–2314Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR: “Mini-Mental State”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975; 12:189–198Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Ballard CG, Bannister C, Graham C, Oyebode F, Wilcock G: Associations of psychotic symptoms in dementia sufferers. Br J Psychiatry 1995; 167:537–540Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Barber R, Scheltens P, Gholkar A, Ballard C, McKeith I, Ince P, Perry R, O’Brien J: White matter lesions on magnetic resonance imaging in dementia with Lewy bodies, Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia, and normal aging. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1999; 67:66–72Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Bassiony MM, Warren A, Rosenblatt A, Baker A, Steinberg M, Steele CD, Lyketsos CG: Isolated hallucinosis in Alzheimer’s disease is associated with African-American race. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2002; 17:205–210Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Bassiony MM, Warren A, Rosenblatt A, Baker A, Steinberg M, Steele CD, Sheppard JE, Lyketsos CG: The relationship between delusions and depression in Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2002; 17:549–556Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Binetti G, Bianchetti A, Padovani A, Lenzi G, De Leo D, Trabucchi M: Delusions in Alzheimer’s disease and multi-infarct dementia. Acta Neurol Scand 1993; 88:5–9Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Caligiuri MP, Peavy G: An instrumental study of the relationship between extrapyramidal signs and psychosis in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2000; 12:34–39Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Cohen D, Eisdorfer C, Gorelick P, Paveza G, Luchins DJ, Freels S, Ashford JW, Semla T, Levy P, Hirschman R: Psychopathology associated with Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders. J Gerontol 1993; 48:M255-M260Google Scholar

36. Cooper JK, Mungas D, Weiler PG: Relations of cognitive status and abnormal behaviors in Alzheimer’s disease. J Am Geriatr Soc 1990; 38:867–870Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Della Sala S, Francescani A, Muggia S, Spinnler H: Variables linked to psychotic symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease. Eur J Neurol 1998; 5:553–560Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Farber NB, Rubin EH, Newcomer JW, Kinscherf DA, Miller JP, Morris JC, Olney JW, McKeel DW: Increased neocortical neurofibrillary tangle density in subjects with Alzheimer disease and psychosis. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000; 57:1165–1173Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Forstl H, Burns A, Levy R, Cairns N: Neuropathological correlates of psychotic phenomena in confirmed Alzheimer’s disease. Br J Psychiatry 1994; 165:53–59Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. Frisoni GB, Rozzini L, Gozzetti A, Binetti G, Zanetti O, Bianchetti A, Trabucchi M, Cummings JL: Behavioral syndromes in Alzheimer’s disease: description and correlates. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 1999; 10:130–138Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41. Geroldi C, Akkawi NM, Galluzzi S, Ubezio M, Binetti G, Zanetti O, Trabucchi M, Frisoni GB: Temporal lobe asymmetry in patients with Alzheimer’s disease with delusions. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2000; 69:187–191Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

42. Gormley N, Rizwan MR: Prevalence and clinical correlates of psychotic symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1998; 13:410–414Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

43. Harwood DG, Barker WW, Ownby RL, Duara R: Prevalence and correlates of Capgras syndrome in Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1999; 14:415–420Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

44. Harwood DG, Barker WW, Ownby RL, Duara R: Clinical characteristics of community-dwelling black Alzheimer’s disease patients. J Natl Med Assoc 2000; 92:424–429Medline, Google Scholar

45. Hirono N, Mori E, Yasuda M, Ikejiri Y, Imamura T, Shimomura T, Ikeda M, Hashimoto M, Yamashita H: Factors associated with psychotic symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1998; 64:648–652Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

46. Hirono N, Mori E, Yasuda M, Imamura T, Shimomura T, Hashimoto M, Tanimukai S, Kazui H, Yamashita H: Lack of effect of apolipoprotein E e4 allele on neuropsychiatric manifestations in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1999; 11:66–70Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

47. Hwang JP, Yang CH, Tsai SJ, Liu KM: Psychotic symptoms in psychiatric inpatients with dementia of the Alzheimer and vascular types. Chin Med J 1996; 58:35–39Google Scholar

48. Jeste DV, Wragg RE, Salmon DP, Harris MJ, Thal LJ: Cognitive deficits of patients with Alzheimer’s disease with and without delusions. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:184–189Link, Google Scholar

49. Kloszewska I: Incidence and relationship between behavioural and psychological symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Psychiatry 1998; 13:785–792Crossref, Google Scholar

50. Kotrla KJ, Chacko RC, Harper RG, Jhingran S, Doody R: SPECT findings on psychosis in Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:1470–1475Link, Google Scholar

51. Leroi I, Voulgari A, Breiner JC, Lyketsos CG: The epidemiology of psychosis in dementia. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2003; 11:83–91Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

52. Lopez OL, Becker JT, Sweet RA, Klunk W, Kaufer DI, Saxton J, Habeych M, DeKosky ST: Psychiatric symptoms vary with the severity of dementia in probable Alzheimer’s disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2003; 15:346–353Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

53. Lyketsos CG, Baker L, Warren A, Steele C, Brandt J, Steinberg M, Kopunek S, Baker A: Depression, delusions, and hallucinations in Alzheimer’s disease: no relationship to apolipoprotein E genotype. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1997; 9:64–67Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

54. Lyketsos CG, Sheppard JE, Steinberg M, Tschanz JT, Norton MC, Steffens DC, Breitner JC: Neuropsychiatric disturbance in Alzheimer’s disease clusters into three groups: the Cache County Study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2001; 16:1043–1053Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

55. Mendez M, Martin R, Smyth KA, Whitehouse PJ: Psychiatric symptoms associated with Alzheimer’s disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1990; 2:28–33Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

56. Nambudiri DE, Teusink JP, Fensterheim L, Young RC: Age and psychosis in degenerative dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1997; 12:11–14Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

57. Patterson M, Schnell A, Martin R, Mendez M, Smyth K: Assessment of behavioral and affective symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 1990; 3:21–30Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

58. Rocchi A, Micheli D, Ceravolo R, Manca ML, Tognoni G, Siciliano G, Murri L: Serotoninergic polymorphisms (5-HTTLPR and 5-HT2A): association studies with psychosis in Alzheimer disease. Genet Test 2003; 7:309–314Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

59. Rubin EH, Kinscherf DA, Morris JC: Psychopathology in younger versus older persons with very mild and mild dementia of the Alzheimer type. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:639–642Link, Google Scholar

60. Sweet RA, Hamilton RL, Lopez OL, Klunk WE, Wisniewski SR, Kaufer DI, Healy MT, DeKosky ST: Psychotic symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease are not associated with more severe neuropathologic features. Int Psychogeriatr 2000; 12:547–558Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

61. Ballard CG, O’Brien JT, Swann AG, Thompson P, Neill D, McKeith IG: The natural history of psychosis and depression in dementia with Lewy bodies and Alzheimer’s disease: persistence and new cases over 1 year of follow-up. J Clin Psychiatry 2001; 62:46–49Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

62. Burns A, Jacoby R, Levy R: Psychiatric phenomena in Alzheimer’s disease, I: disorders of thought content; II: disorders of perception. Br J Psychiatry 1990; 157:72–76Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

63. Caligiuri MP, Peavy G, Salmon DP, Galasko DR, Thal LJ: Neuromotor abnormalities and risk for psychosis in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 2003; 61:954–958Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

64. Chen JY, Stern Y, Sano M, Mayeux R: Cumulative risks of developing extrapyramidal signs, psychosis, or myoclonus, in the course of Alzheimer’s disease. Arch Neurol 1991; 48:1141–1143Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

65. Chui HC, Lyness SA, Sobel E, Schneider LS: Extrapyramidal signs and psychiatric symptoms predict faster cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease. Arch Neurol 1994; 51:676–681Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

66. Haupt M, Kurz A, Janner M: A 2-year follow-up of behavioural and psychological symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2000; 11:147–152Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

67. Holtzer R, Tang M, Devanand DP, Albert SM, Wegesin DJ, Marder K, Bell K, Albert M, Brandt J, Stern Y: Psychopathological features in Alzheimer’s disease: course and relationship with cognitive status. J Am Geriatr Soc 2003; 51:953–960Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

68. McShane R, Gedling K, Reading M, McDonald B, Esiri MM, Hope T: Prospective study of relations between cortical Lewy bodies, poor eyesight, and hallucinations in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1995; 59:185–188Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

69. Paulsen JS, Salmon DP, Thal LJ, Romero R, Weisstein-Jenkins C, Galasko D, Hofstetter CR, Thomas R, Grant I, Jeste DV: Incidence of and risk factors for hallucinations and delusions in patients with probable AD. Neurology 2000; 54:1965–1971Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

70. Rosen J, Zubenko GS: Emergence of psychosis and depression in the longitudinal evaluation of Alzheimer’s disease. Biol Psychiatry 1991; 29:224–232Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

71. Stern Y, Albert M, Brandt J, Jacobs DM, Tang M-X, Marder K, Bell K, Sano M, Devanand DP, Bylsma F, Lafleche G: Utility of extrapyramidal signs and psychosis as predictors of cognitive and functional decline, nursing home admission, and death in Alzheimer’s disease: prospective analyses from the predictors study. Neurology 1994; 44:2300–2307Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

72. Sweet RA, Nimgaonkar VL, Kamboh MI, Lopez OL, Zhang F, DeKosky ST: Dopamine receptor genetic variation, psychosis, and aggression in Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol 1998; 55:1335–1340Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

73. Sweet RA, Kamboh I, Wisniewski SR, Lopez OL, Klunk WE, Kaufer DI, DeKosky ST: Apolipoprotein E and alpha-1-antichymotrypsin genotypes do not predict time to psychosis in Alzheimer’s disease. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 2002; 15:24–30Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

74. Wilson RS, Gilley DW, Bennett DA, Beckett LA, Evans DA: Hallucinations, delusions, and cognitive decline in Alzheimer disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2000; 69:172–177Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

75. Forstl H, Besthorn C, Geiger-Kaibish C, Sattel H, Schreiter-Gasser U: Psychotic features and the course of Alzheimer’s disease: relationship to cognitive, electroencephalographic and computerized tomography findings. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1993; 87:395–399Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

76. Zubenko GS, Moossy J, Martinez AJ, Rao G, Claassen D, Rosen J, Kopp U: Neuropathologic and neurochemical correlates of psychosis in primary dementia. Arch Neurol 1991; 48:619–624Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

77. McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM: Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of the Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology 1984; 34:939–944Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

78. Morris JC, Mohs RC, Rogers H, Fillenbaum G, Heyman A: Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD) clinical and neuropsychological assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Psychopharmacol Bull 1988; 24:641–652Medline, Google Scholar

79. Robins LN, Helzer JE, Croughan J, Ratcliff KS: The National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule: its history, characteristics, and validity. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1981; 38:381–389Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

80. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MB: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, version 2.0. Indianapolis, Lilly Research Laboratories, 1996Google Scholar

81. Mezzich JE, Dow JT, Rich CL, Costello AJ, Himmelhoch JM: Developing an efficient clinical information system for a comprehensive psychiatric institute, II: initial evaluation form. Behav Res Methods Instrum 1981; 13:464–478Crossref, Google Scholar

82. Grossberg GT: Diagnosis and treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. J Clin Psychiatry 2003; 64:3–6Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

83. Farlow M: A clinical overview of cholinesterase inhibitors in Alzheimer’s disease. Int Psychogeriatr 2002; 14:93–126Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

84. Absher JR, Cummings JL: Noncognitive behavioural alterations in dementia syndromes, in Handbook of Neuropsychology, vol 8. Edited by Boller F, Grafman J. Amsterdam, Elsevier Science, 1993, pp 315–338Google Scholar

85. Alexopoulos GS, Streim J, Carpenter D, Docherty JP: Expert consensus panel for using antipsychotic drugs in older patients. J Clin Psychiatry 2004; 65(suppl 2):5–99Google Scholar

86. Jeste DV, Eastham JH, Lacro JP, Gierz M, Field MG, Harris MJ: Management of late-life psychosis. J Clin Psychiatry 1996; 57:39–45Medline, Google Scholar

87. Gladsjo JA, Eastham JH, Jeste DV: Cognitive impairment in older schizophrenia patients, in Schizophrenia and Comorbid Conditions: Diagnosis and Treatment. Edited by Hwang MY, Bermanzzohn P. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2001, pp 125–148Google Scholar

88. Berman I, Merson A, Allan E, Alexis C, Sison C, Losonczy M: Effect of risperidone on cognitive performance in elderly schizophrenic patients: a double-blind comparison with haloperidol, in Abstracts From the 35th Annual Meeting of the New Clinical Drug Evaluation Unit. Rockville, Md, National Institute of Mental Health, 1995, poster 93Google Scholar

89. Berman I, Merson A, Rachov-Pavlov J, Allan E, Davidson M, Losonczy MF: Risperidone in elderly schizophrenia patients: an open-label trial. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 1996; 4:173–179Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

90. Cummings JL, Jeste DV: Alzheimer’s disease and its management in the year 2010. Psychiatr Serv 1999; 50:1173–1177Link, Google Scholar

91. McKeith IG, Perry RH, Fairbairn AF, Jabeen S, Perry EK: Operational criteria for senile dementia of Lewy body type (SDLT). Psychol Med 1992; 22:911–992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar