Systematic Review of Psychological Approaches to the Management of Neuropsychiatric Symptoms of Dementia

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The authors systematically reviewed the literature on psychological approaches to treating the neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia. METHOD: Reports of studies that examined effects of any therapy derived from a psychological approach that satisfied prespecified criteria were reviewed. Data were extracted, the quality of each study was rated, and an overall rating was given to each study by using the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine criteria. RESULTS: A total of 1,632 studies were identified, and 162 satisfied the inclusion criteria for the review. Specific types of psychoeducation for caregivers about managing neuropsychiatric symptoms were effective treatments whose benefits lasted for months, but other caregiver interventions were not. Behavioral management techniques that are centered on individual patients’ behavior or on caregiver behavior had similar benefits, as did cognitive stimulation. Music therapy and Snoezelen, and possibly sensory stimulation, were useful during the treatment session but had no longer-term effects; interventions that changed the visual environment looked promising, but more research is needed. CONCLUSIONS: Only behavior management therapies, specific types of caregiver and residential care staff education, and possibly cognitive stimulation appear to have lasting effectiveness for the management of dementia-associated neuropsychiatric symptoms. Lack of evidence regarding other therapies is not evidence of lack of efficacy. Conclusions are limited because of the paucity of high-quality research (only nine level-1 studies were identified). More high-quality investigation is needed.

The neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia include signs and symptoms of disturbed perception, thought, mood, or behavior (1). Clinically significant neuropsychiatric symptoms are found in about one-third of dementia patients with mild impairment and in two-thirds with more severe impairment (2, 3) and in an even higher proportion of dementia patients in residential care (4, 5). Neuropsychiatric symptoms contribute significantly to caregiver burden, institutionalization (6), and decreased quality of life for patients with dementia (7).

Psychotropic medications are often prescribed for neuropsychiatric symptoms, but concerns have been raised about the safety and efficacy of these medications (8–10). Psychological approaches may have fewer risks, but little is known about their efficacy. We conducted a systematic review of psychological approaches to neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia with the aim of making evidence-based recommendations about the use of these interventions. The review included studies examining any therapy derived from a psychological/psychosocial model. We considered the effects of the interventions in terms of neuropsychiatric symptoms and related outcomes and assessed whether the benefit was time limited or sustained.

Method

Search Strategy

We searched electronic databases through July 2003, reference lists from individual and review articles, and the Cochrane Library and sought expert knowledge of additional studies, even those published after July 2003. We also hand-searched the contents of three journals published during the 10-year period up to July 2003.

We used search terms encompassing individual dementias and interventions. We included studies with quantitative outcome measures that were either direct or proxy measures of neuropsychiatric symptoms (e.g., care costs, quality of life, institutionalization, and decreased medication or restraint). Studies of people without dementia, dementia secondary to head injury, or interventions that either involved medication or were not based on a psychological model (e.g., aromatherapy, homeopathy, occupational therapy, light therapy) were excluded.

Data Extraction Strategy

We used a tool adapted from a review of checklists (11). Ratings of the level of evidence were assigned to studies according to the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine guidelines (http://www.cebm.net/levels_of_evidence.asp#levels). Levels of evidence grades ranged from 1 to 5, with lower numbers indicating higher quality. Each type of intervention was then given an overall “grade of recommendation” according to the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine criteria. The grades ranged from A (consistent level of evidence grade of 1) to D (level of evidence grade of 5 or troublingly inconsistent or inconclusive studies at any level).

Results

We identified 1,632 references; 1,421 were excluded and 162 were included.

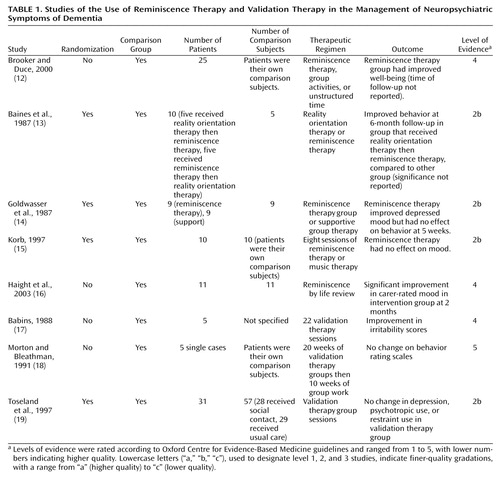

Reminiscence Therapy

Reminiscence therapy (Table 1) uses materials such as old newspapers and household items to stimulate memories and enable people to share and value their experiences. We identified five studies of reminiscence therapy interventions (12–16). Three were small randomized, controlled trials. One had 10 participants and reported behavioral improvements when reminiscence therapy was preceded by reality orientation, but not vice versa (13). The improvement was not clearly significant. The other two studies found no benefit of reminiscence therapy (14, 15). Two level-4 studies had small numbers (12, 16). One reported a significant improvement in mood, although the raters were not masked to participants’ treatment group (16).

| • | • We assigned a grade of recommendation of D to reminiscence therapy. | ||||

| • | |||||

| • | |||||

Validation Therapy

Validation therapy (Table 1), rooted within the Rogerian humanistic psychology premise of individual uniqueness, is intended to give an opportunity to resolve unfinished conflicts by encouraging and validating expression of feelings. We identified three studies of validation therapy. The first, a case series of five individuals, indicated an improvement in irritability after validation therapy (17). The second, which included five patients who served as their own comparison subjects, reported no change in behavior (18). A randomized, controlled trial compared validation therapy to usual care or a social contact group in 88 patients with dementia (19). Although at 1-year follow-up the nursing staff thought the validation therapy group improved, there was no difference in independent outcome ratings, in nursing time needed, or in use of psychotropic medication and restraint.

| • | • Because of the absence of conclusive evidence, we assigned a grade of recommendation of D to validation therapy. | ||||

| • | |||||

Reality Orientation Therapy

Reality orientation therapy (Table 2) is based on the idea that impairment in orientating information (day, date, weather, time, and use of names) prevents patients with dementia from functioning well and that reminders can improve functioning. Eleven studies assessed reality orientation therapy (13, 20–29). The strongest randomized, controlled trial, which had 57 participants, showed no immediate benefit of reality orientation therapy, compared to active ward orientation (24). In a smaller randomized, controlled trial (N=10), patients who received reality orientation therapy followed by reminiscence therapy had fewer neuropsychiatric symptoms, compared to patients who received the treatments in the reverse order (13). The other smaller nonrandomized, controlled trials mostly found benefits in the reality orientation therapy groups in terms of improved mood, decreased neuropsychiatric symptoms, or delayed institutionalization.

| • | • The grade of recommendation for reality orientation therapy is D. | ||||

| • | |||||

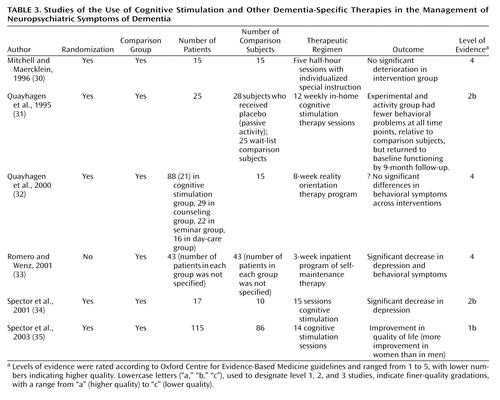

Cognitive Stimulation Therapy

Cognitive stimulation therapy (Table 3), derived from reality orientation therapy, uses information processing rather than factual knowledge to address problems in functioning in patients with dementia. Three of four randomized, controlled trials of cognitive stimulation therapy (31, 32, 34, 35) showed some positive results, although the studies used different follow-up endpoints (immediately after therapy to 9 months after therapy). There were early behavior improvements, relative to waiting list. By 9 months, no significant difference between groups was found. One study showed reduced depression, and another showed improvement in quality of life but not in mood (34, 35). The final study did not report whether the differences in behavior were significant (32).

| • | • Given the mostly consistent evidence that cognitive stimulation therapy improves aspects of neuropsychiatric symptoms immediately and for some months afterward, our consensus is that the grade of recommendation is B, although the evidence is not consistent in all respects. | ||||

| • | |||||

Other Dementia-Specific Therapies

We identified two other dementia-specific therapies (30, 33) (Table 3). The first, “individualized special instruction,” consisted of 30 minutes of focused individual attention and participation in an activity appropriate for each individual (30). The participants in the pilot randomized, controlled trial were their own waiting-list comparison subjects. During the intervention period, their behavior did not deteriorate, compared with deteriorating behavior before the intervention period.

The second dementia-specific therapy was “self-maintenance therapy,” which is intended to help the patient maintain a sense of personal identity, continuity, and coherence (33). This intervention incorporates techniques from validation, reminiscence, and psychotherapy. A 3-week admission of patients and caregivers to a specialist unit in which self-maintenance therapy was provided led to a significant decrease in depression and problematic behavior, compared to baseline. This outcome may have been partly attributable to the environment.

| • | • These level-4 studies support a grade of recommendation of C for both interventions. | ||||

| • | |||||

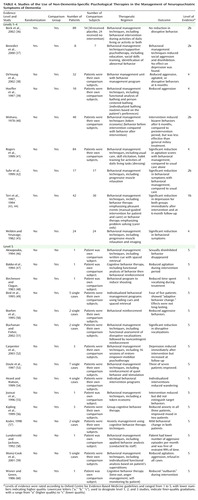

Non-Dementia-Specific Therapies

Twenty-five reports described use of non-dementia-specific psychological therapies for patients with dementia (36–60) (Table 4). Nearly all of the studies examined behavioral management techniques. In one large randomized, controlled trial, participants received either manual-guided treatment for the patient and caregiver or a problem-solving treatment for the caregiver only (43). The two interventions were equally successful in improving depressive symptoms immediately and at 6-month follow-up (43, 44). Two other small randomized, controlled trials also had positive results (37, 42). In one of those studies, participants had significantly fewer neuropsychiatric symptoms 2 months after being taught progressive muscle relaxation. In the other study, the behavior of patients with the dementia of multiple sclerosis improved with “neuropsychological counseling” (a cognitive behavior intervention). There were two other randomized, controlled trials in which behavioral management techniques were used (36, 40); these techniques were ineffective in one of the studies (36). It used a complex, difficult-to-classify intervention that included a variety of techniques (e.g., life review, sensory stimulation, single-word commands, and problem-oriented strategies) (36). The second used a token economy, which was more effective in reducing “bizarre” behavior in patients with severe dementia, compared to a preintervention condition, but less effective than a milieu treatment (40). Several single-case studies are summarized in Table 4.

| • | • The grade of recommendation for standard behavioral management techniques in dementia is B. The findings of the larger randomized, controlled trials were consistent and positive, and the effects lasted for months. | ||||

| • | |||||

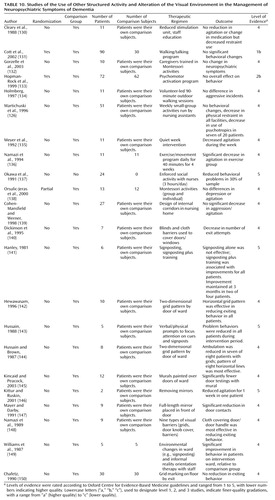

Psychological Interventions With Caregivers

Table 5 and Table 6 summarize 19 reports that describe interventions with family caregivers designed to ameliorate neuropsychiatric symptoms or frequency of institutionalization in dementia (61–79). Seven studies involved training the caregiver to use behavioral management techniques (Table 5). A randomized, controlled trial (65) found no difference in agitation or global outcome in a comparison of treatment with behavioral management techniques, haloperidol or trazodone alone, or placebo at 16 weeks. Behavioral management techniques taught to caregivers did not reduce psychotropic drug use or symptom frequency at 1-year follow-up (67). Exercise and behavioral management techniques led to significant improvements in depression at 3 months but not at 2 years (66). In a smaller randomized, controlled trial, behavioral management techniques based on the progressive Lowered Stress Threshold Model were taught to caregivers with the aim of reducing stimulation in response to specific stressors identified by caregivers (63). Both study groups received the intervention, one in the form of written materials, and the other in a training program. A positive effect for care recipients was found in the second group. The evidence that behavioral management techniques with caregivers and exercise training with patients helps depression is strong, but it is unclear which component was the active component.

| • | • Because the findings of other studies are inconsistent, the grade of recommendation for teaching caregivers behavioral management techniques to manage psychological symptoms is D. | ||||

| • | |||||

Table 6 summarizes the results of nine studies (seven randomized, controlled trials) involving psychoeducation to teach caregivers how to change their interactions with patients with dementia. In one large trial, improvement in neuropsychiatric symptoms at 16 weeks was found, but the difference only approached significance (73). In a second trial, primarily powered to improve mental health in caregivers rather than in patients, improvement in neuropsychiatric symptoms occurred immediately after 12 weeks of training in stress management, dementia education, and coping skills but was not maintained at 3-month follow-up (69). A third, smaller trial examining the effects of an intervention with individual families found significant improvements at 6 months in mood and ideational disturbance (74). In a randomized, controlled trial of an educational program for family carers that included supportive counseling, psychoeducation and training in management strategies, and home visits, the rate of institutionalization of patients was decreased (70). The effect continued for 3 months but not 2 years. A fifth randomized, controlled trial involved psychoeducation, instruction to caregivers in how to change their interactions with the patient, or both (68). Patients’ behavior improved at 6 months, but the difference only approached significance. The researchers attributed the nonsignificant result to the fact that the trial was a pilot study that had limited power. Another study examined the effects of caregiver psychoeducation in working with nursing home residents to enhance social activities and self-care; the intervention resulted in a decrease in agitation after 6 months (77). Finally, a level-1 study investigated a comprehensive support and counseling intervention for spouse caregivers that included problem solving, management of troublesome behavior, education, and increased practical support, followed by long-term support groups (78). Patients’ neuropsychiatric symptoms were not directly measured, but the intervention was found to delay time to institutionalization by nearly a year. The other studies were noncontrolled and showed either improvement that approached significance or significant improvement (71, 72).

| • | • The grade of recommendation for behavioral management techniques in the form of psychoeducation and teaching caregivers how to change their interactions with patients is A, because evidence from level-1, level-2, and level-4 studies consistently supports these interventions, and the effects have been shown to last months. | ||||

| • | |||||

An uncontrolled study suggested that family counseling is helpful in reducing institutionalization of patients (76). In a nonrandomized, controlled trial, a family support group resulted in a decrease in problem behavior but not in depression (75).

| • | • The grade of recommendation for family counseling is C, because the intervention is supported by two level-4 studies. | ||||

| • | |||||

A single controlled study compared the effects of “admiral” nurses—specialists in treatment of dementia who worked in the community with persons caring for patients with dementia—to those of usual treatment and showed no effect on institutionalization of patients (79).

| • | • The grade of recommendation for caregiver support by specialist nurses in the community is D. | ||||

| • | |||||

Psychosocial Interventions

Sensory enhancement

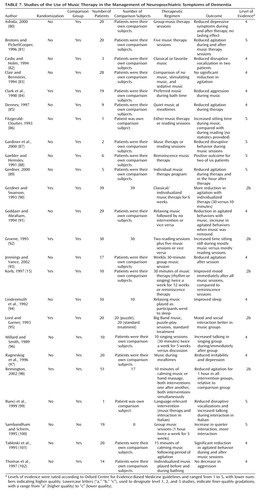

Music/music therapy

Music/music therapy interventions (Table 7) included playing music from specific eras or particular genres, such as Big Band music, as part of activity sessions or at certain times of day, including mealtimes or bath times. Participants also played musical instruments, moved to music, or participated in composition and improvisation sessions. Of 24 music/music therapy interventions (15, 80–102), six were investigated in randomized, controlled trials (15, 84, 89, 92, 95, 98). All were small trials and showed improvements in disruptive behavior. In two, behavior was observed during the music sessions, but there was no evidence that benefit carried over after the sessions (84, 92). In three studies, behavioral change was observed outside of the music/music therapy session. In the first study, patients were significantly less agitated, both during and immediately after music/music therapy in which the music was chosen to fit the individuals’ preference (89). The results of the second study were similar (95). In the third study, which assessed music, hand massage, or a combination of both for 10 minutes, decreased agitation was observed 1 hour after the intervention (98). All but one of the other studies (100) were controlled. Most of them found a benefit, although some did not (83).

| • | • The grade of recommendation for music therapy for immediate amelioration of disruptive behavior is B, because consistent level-2 evidence suggests that music therapy decreases agitation during sessions and immediately after. There is, however, no evidence that music therapy is useful for treatment of neuropsychiatric symptoms in the longer term. | ||||

| • | |||||

Snoezelen therapy/multisensory stimulation

Snoezelen therapy/multisensory stimulation (Table 8), which combines relaxation and exploration of sensory stimuli, such as lights, sounds, and tactile sensations, is based on the idea that neuropsychiatric symptoms may result from periods of sensory deprivation. Interventions occurred in specially designed rooms and lasted 30–60 minutes. Of six trials of Snoezelen therapy/multisensory stimulation, three were randomized, controlled trials. The first was a very small trial with no clear results (103). The other two found that disruptive behavior briefly improved outside the treatment setting but that there was no effect after the treatment had stopped (104, 105). The other reports described studies of individual cases (106, 107) and an uncontrolled trial in which improvements were found but no statistics were provided (108).

| • | • The grade of recommendation for Snoezelen for amelioration of disruptive behavior immediately after the intervention is B, on the basis of consistent evidence from level-2 studies. The effects are apparent only for a very short time after the session. | ||||

| • | |||||

Other sensory stimulation

Of seven trials of other forms of sensory stimulation (Table 8), three were randomized, controlled trials. The first trial compared massage with a comparison condition, music, or a combination of massage and music (98). Decreased agitation was observed 1 hour after the intervention. The second trial examined a sensory integration program that emphasized bodily responses, sensory stimulation, and cognitive stimulation; this intervention had no effect on behavior (112). Similarly, a small randomized, controlled trial found that white noise had no effect on sleep disturbance and nocturnal wandering (114). An “expressive physical touch” intervention (5.5 minutes/day of touching, including 2.5 minutes/day of gentle massage and 3 minutes/day of intermittent touching with some talking) over a 10-day period decreased disturbed behavior from baseline immediately and for 5 days after the intervention (111). White noise tapes led to immediate decrease in agitation (109). A controlled trial of stimulation with “natural elements” while bathing (sounds of birds, brooks, and small animals were played and large bright pictures were displayed) found that agitation decreased significantly only during bathing (115). The other study of single cases found no difference in agitation before and after therapeutic touch or massage (113). In the final two studies, the effects of several forms of sensory stimulation involving touch, smell, and taste were examined. A small randomized, controlled trial reported no change associated with the intervention (110), and the other study found that the intervention was helpful (116).

| • | • The grade of recommendation for short-term benefits of sensory stimulation is C, but there is no evidence for sustained usefulness. | ||||

| • | |||||

Simulated presence therapy

Six studies investigated the effects of simulated presence therapy, in which positive autobiographical memories are presented to the patient in the form of a telephone conversation usually involving a continuous-play audiotape made by a family member or surrogate (Table 9). One randomized, controlled trial found no change in agitated or withdrawn behaviors (117). Staff observations suggested reduced agitation in patients who received the intervention, compared to a placebo group but not compared to patients receiving usual care (117). A small study found improved social interaction and attention (118). Simulated presence therapy used to address agitation led to significant decreases in agitation and improved social interaction but no change in aggressive behaviors (119). When simulated presence therapy was used regularly, problem behaviors were reduced by 91% (119). Finally, in a series of single case studies, Peak and Cheston (120) reported mixed results, with increased ill-being in one participant and reduced anxiety and increased social interaction in other participants. Use of video to provide simulated presence was not associated with significant changes in agitated behavior (121).

| • | • The grade of recommendation for simulated presence therapy is D. | ||||

| • | |||||

Structured activity

Therapeutic activity programs

There were five randomized, controlled trials of therapeutic activities (Table 9). In a small-scale randomized, controlled trial, therapeutic activities at home were associated with significant decreases in agitation (123). Another study found that small group discussion and being carried on a bicycle pedaled by volunteers alleviated patients’ depression but not agitation at 10 weeks (122). The third found no effects of puzzle play on social interaction and mood (95). Similarly, a comparison of games and puzzle play with Snoezelen and another study comparing structured activity with a control condition found no improvements in mood and behavior (104, 129).

The other studies of therapeutic activities were nonrandomized, controlled trials. Ishizaki et al. (124) found no beneficial effects of weekly therapeutic activities on depression. In another study, a combination of group and individualized activity sessions in day care significantly increased agitation over 10 weeks (125). A controlled, nonrandomized clinical trial of weekly activity groups led by nursing assistants found no behavioral changes (126). There was, however, less use of physical restraint generally, and psychotropic medication use was reduced in seven of 20 participants. A specialist day-care program providing structured daily activities for patients with dementia was associated with decreased institutionalization and was more cost-effective than nursing home care (29). Patients who were rocked on a swing did not show a decrease in aggression (128). Three case studies of diverse group activities (games, music, exercise, socializing) found equivocal effects on behavior (127). In two studies that used reading sessions as an intervention, some improvement was seen in wandering (86) and disruptive behaviors were decreased in both patients in the study both during and 1 week after the reading intervention (87).

| • | • Not all therapeutic activity programs used the same interventions, but overall, the study findings are inconsistent and inconclusive. The grade of recommendation is D. | ||||

| • | |||||

Montessori activities

Montessori activities use rehabilitation principles and make extensive use of external cues and progression in activities from simple to complex (Table 10). Three nonrandomized, controlled trials utilized Montessori-based activities and found no change in depression and agitation (132, 135, 138).

| • | • The grade of recommendation for Montessori activities is D. | ||||

| • | |||||

Exercise

Three studies examined the use of exercise/movement/walking as an intervention for neuropsychiatric symptoms (Table 10). A well-conducted randomized, controlled trial found no effects on behavior in a “walk-talk” program in which one caregiver walked with two residents or walked and talked with two residents (131). A randomized, controlled trial of a psychomotor activation program found no behavioral effect (133). The other two studies were nonrandomized, controlled trials. One study, in which 11 patients were their own comparison subjects, found a significant reduction in aggressive behaviors on days when a walking group was held (134). The other study, a small matched, controlled trial of exercise groups, found no significant reduction in agitated behaviors (136).

| • | • The grade of recommendation for exercise is D. | ||||

| • | |||||

Social interaction

A small report of single cases studies showed decreased neuropsychiatric symptoms in one-third of patients who had enforced social interaction with nurses for 3 hours/day for 1–2 months (137).

| • | • The grade of recommendation for enforced social interaction is D. | ||||

| • | |||||

Decreased sensory stimulation

Two small studies investigated decreased sensory stimulation (Table 10). A “quiet week” intervention (turning off the television, lowering voices. and reducing fast movement by staff at a day center) led to an immediate significant reduction in agitation as measured by a nonstandardized scale, compared to the period before the intervention (135). In another study, patients on a specially designed reduced stimulation unit—without television, radio, telephones; with scheduled rest periods and limited access to visitors—had no reduction in neuropsychiatric symptoms as measured by a standardized scale, compared with the period before the intervention, but use of restraint decreased (130).

| • | • The grade of recommendation for decreased sensory stimulation is D. | ||||

| • | |||||

Environmental manipulation

Visually complex environments

Eight studies (no randomized, controlled trials) investigated the effects of changing the visual environment (Table 10). The presence of two-dimensional grids on the floor near doors did not reduce exiting behaviors (150). However, two studies in which a horizontal grid pattern was used reported significant decreases in patients’ attempts to open doors and in patients’ ambulation (142, 144). Similar results were found in a study of the effects of murals on the walls above doorways (145). Blinds and cloth barriers placed over doors/door handles and signs installed to provide a focus of patients’ attention were also effective in reducing time spent attempting to exit the ward (140, 143, 148). Enhancement of the visual environment in a selected area of a residential home was associated with a decrease in agitated behaviors, although the finding was not statistically significant (139).

| • | • Consistent evidence from level-4 studies for changing the environment to obscure the exit indicates a grade of recommendation of C. | ||||

| • | |||||

Mirrors

Two small nonrandomized, controlled trials investigated the effects of mirrors in the patient’s environment (Table 10). In a study with a single case design, one of two patients was less agitated after removal of mirrors from the ward environment (146). Placing a full-length mirror over a doorway led to a significant decrease in exiting during the intervention for nine patients (147).

| • | • The grade of recommendation for use of mirrors is D. | ||||

| • | |||||

Signposting

Three nonrandomized, controlled trials investigated the effects of signposting on neuropsychiatric symptoms (Table 10). Two single case studies found that signposting alone was ineffective, but signposting in combination with reality orientation therapy led to improvements in ward orientation in two of four and five of five patients, respectively (141, 149). In the third study, signposts were placed alongside prompts that served to draw attention to the signs; this arrangement led to a reduction in neuropsychiatric symptoms in all five study participants (143).

| • | • The grade of recommendation for signposting is D. | ||||

| • | |||||

Other environmental manipulations

Group living

Group living is the name given to specially designed nursing homes that encourage a homelike atmosphere (Table 11). In a randomized, controlled trial, no change in neuropsychiatric symptoms was found in those in a group living setting, compared to community-dwelling waiting-list comparisons (155). Two other randomized, controlled trials showed decreased aggression, anxiety, and depression and less use of neuroleptic medication for 1 year in residents in group living settings (151, 152). No differences between group living and comparison subjects were observed 3 years later. Both studies were limited, because residents were selected for admission and were ineligible if they had frontal lobe symptoms, severe dementia, or a severe physical morbidity. A smaller uncontrolled trial of group living reported beneficial effects on neuropsychiatric symptoms at 6 months and reduced use of physical restraints (153). However, in another study, neuropsychiatric symptoms significantly increased in group living subjects, relative to comparison subjects, at 6 months and 1 year (156). In summary, group living may have beneficial or deleterious effects—or no effect—on neuropsychiatric symptoms.

| • | • The grade of recommendation for group living is D. | ||||

| • | |||||

Unlocking doors

One small uncontrolled study examined the effect of unlocking ward doors for 3-hour periods (154) (Table 11). Patients showed fewer neuropsychiatric symptoms and decreased wandering when the door was open (154).

| • | • The grade of recommendation for unlocking doors is D. | ||||

| • | |||||

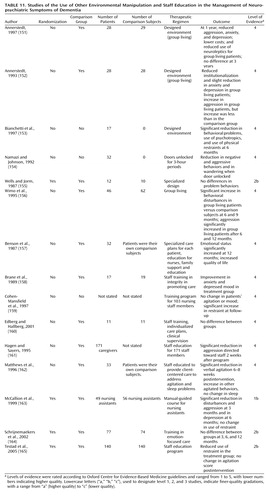

Staff education in managing behavioral problems

Nine studies investigated the effects of staff education in treatment of neuropsychiatric symptoms. Three of the studies were randomized, controlled trials (163–165) (Table 11). A randomized, controlled trial of communication skills training for nursing and auxiliary staff showed significant reductions in patients’ aggression at 3 months and in patients’ depression at 6 months (163). Education of staff to implement an emotion-focused care program (validation, reminiscence, sensory stimulation) did not result in any change in neuropsychiatric symptoms (164). Staff education programs focused on knowledge of dementia and potential management strategies reduced use of physical restraint use (165) and, in a nonrandomized, controlled trial, decreased aggressive behavior toward staff (161). Specialized care programs for individuals in a residential home plus staff education improved emotional status and quality of life for residents 12 months later (157). A similar approach in a controlled trial with only 11 people in each arm led to nonsignificant differences favoring the intervention group (160). The result of a client-centered approach to agitation and sleep disturbance for 33 residents of a nursing home was equivocal. Verbal aggression decreased significantly, but the (less frequent) episodes of nonverbal agitation increased (162). Training staff in integrity-promoting care (staff gave more time, made the environment more homelike, encouraged patients to do more and to wear their own clothes) improved patients’ anxiety and depressed mood in a small controlled trial (158). In a large uncontrolled trial, training for nursing staff in using unstandardized observational outcomes led to an increase in restraint use but had no effect on agitated behavior (159).

| • | • The grade of recommendation for specific staff education programs in managing neuropsychiatric symptoms is B, on the basis of consistent evidence from level-1 and level-2 studies, as well as supportive evidence from level-4 studies. | ||||

| • | |||||

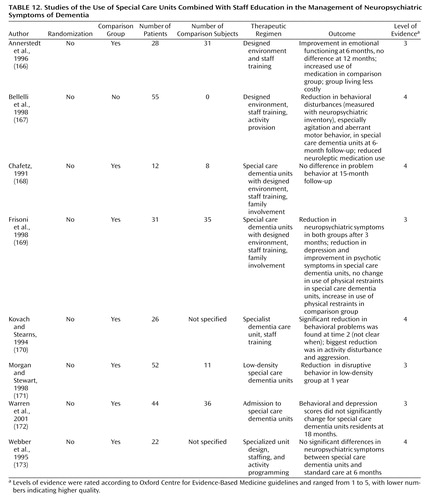

Environmental interventions combined with staff education

Eight nonrandomized, controlled trials investigated the effects of environmental interventions such as special care units designed for patients with dementia and staffed by specially trained workers who received ongoing training (Table 12). In a controlled trial, admission to a “low-density” special care dementia unit, which had fewer residents and larger living areas than standard units, was associated with a decrease in disruptive behavior (171). Similarly, in a controlled trial, a combination of group living and staff training was found to improve patients’ emotional and physical outcomes and was less costly than standard care (166, 167). In other studies, special care dementia units were associated with a reduction in neuropsychiatric symptoms, especially agitation and depression, and with a reduction in use of neuroleptic medication (167, 169). Aggression and activity disturbances were reduced in a small controlled trial of a special care dementia unit care (170). However, three other studies found no effect (168, 172, 173).

| • | • The grade of recommendation for special care units combined with staff education is D. | ||||

| • | |||||

Discussion

We found numerous studies reporting psychological approaches to neuropsychiatric symptoms. We have tried to summarize and classify these studies using evidence-based guidelines in order to help clinicians understand which interventions are efficacious and over what time period. We also tried to distinguish interventions that are ineffective from interventions for which too little evidence is available to judge their effectiveness. Because some interventions are made up of several elements, we could have classified them in different ways. We tried to use the best fit and, by describing the interventions, to make our judgments transparent. Some therapies may require a huge amount of work for very little benefit, and we did not measure this aspect. In addition, some therapies may provide pleasure (either for the patients with dementia or for staff members) and thus may be worthwhile even if the intervention does not alter the patients’ neuropsychiatric symptoms. We did not attempt to judge these differential effects. Similarly, we did not study cognition as an endpoint, although some therapies are intended to have an effect on cognition.

Effective Psychological Therapies

Behavioral management techniques centered on individual patients’ behavior are generally successful for reduction of neuropsychiatric symptoms, and the effects of these interventions last for months, despite qualitative disparity. Psychoeducation intended to change caregivers’ behavior is effective, especially if it is provided in individual rather than group settings, and improvements in neuropsychiatric symptoms associated with these interventions are sustained for months. We therefore recommend these types of interventions.

Music therapy and Snoezelen, and possibly some types of sensory stimulation, are useful treatments for neuropsychiatric symptoms during the session but have no longer-term effects. The cost or complexity of Snoezelen for such small benefit may be a barrier to its use.

Specific types of staff education lead to reductions in behavioral symptoms and use of restraints and to improved affective states. Staff education is, however, heterogeneous, although instruction for staff in communication skills and enhancement of staff members’ knowledge about dementia may improve many outcomes related to neuropsychiatric symptoms. Teaching staff to use dementia-specific psychological therapies for which there is limited evidence of efficacy may not improve these outcomes.

What Interventions Need More Evidence?

Little evidence is available on the effectiveness of reminiscence therapy, but more positive evidence exists for cognitive stimulation therapy. Training for caregivers in behavioral management techniques had inconsistent outcomes but merits further study. The evidence for therapeutic activities is very mixed, and the study findings for these interventions are contradictory and inconclusive. Specialized dementia units were not consistently beneficial, but changing the environment visually and unlocking doors successfully reduced wandering in institutions. These promising interventions merit more study. There is no convincing evidence that simulated presence interventions or reduced stimulation units are efficacious for neuropsychiatric symptoms.

Which Interventions Were Ineffective?

Reality orientation therapy, validation therapy, “admiral” nurses, and Montessori activities had no effect on neuropsychiatric symptoms. In addition, convincing evidence suggests that simple repetitive exercise does not work for neuropsychiatric symptoms.

Conclusions

Overall our conclusions are limited because of the paucity of high-quality research. We found only nine studies with level-1 evidence. However, lack of evidence of efficacy does not mean lack of efficacy. Because the system of rating research assigns the highest ratings to randomized, controlled trials, most published studies of psychological interventions will not be rated as having the highest quality. The literature on behavioral interventions places greater weight on experimental single case studies, particularly in describing individualized interventions. The purpose of publication, however, is to provide evidence that can be generalized for future use. We have, therefore, used the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine’s system for assessing evidence. We encourage the use of standardized interventions (which can be individualized within a context of adherence to basic principles) in future research so that interventions found to be effective can be used in other populations.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Received Nov. 15, 2004; revisions received Jan. 9 and Jan. 24, 2005; accepted Feb. 22, 2005. From the Department of Mental Health Sciences, University College London. Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. Livingston, Department of Mental Health Sciences, University College London, Holborn Union Building, Archway Campus, Highgate Hill, London, UK, N19 5LW; [email protected] (e-mail). The Old Age Task Force of the World Federation of Biological Psychiatry includes John Copeland, M.D., F.R.C.P., F.R.C.Psych., Bob Woods, M.Sc., Linda Teri, Ph.D., Henry Brodaty, A.O., M.B.B.S., M.D., F.R.A.C.P., F.R.A.N.Z.C.P., Pedro Ridruejo, Yong Ku Kim, M.D., Ph.D., Masatoshi Takeda, M.D., Ph.D., Manabu Ikeda, M.D., Ph.D., Dan Blazer, M.D., Ph.D., Carlos Augusto de Mendonca Lima, M.D., D.Sci., and Sirkka-Liisa Kivela, M.D.

1. Finkel S, Costa e Silva J, Cohen G, Miller S, Sartorius N: Behavioral and psychological signs and symptoms of dementia: a consensus statement on current knowledge and implications for research and treatment. Int Psychogeriatr 1996; 8(suppl 3):497–500Google Scholar

2. Lyketsos CG, Steinberg M, Tschanz JT, Norton MC, Steffens DC, Breitner JCS: Mental and behavioral disturbances in dementia: findings from the Cache County Study on Memory in Aging. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:708–714Link, Google Scholar

3. Lyketsos C, Lopez O, Jones B, Fitzpatrick A, Breitner J, DeKosky S: Prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia and mild cognitive impairment. JAMA 2002; 288:1475–1483Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Margallo-Lana M, Reichelt K, Hayes P, Lee L, Fossey J, O’Brien J, Ballard C: Longitudinal comparison of depression, coping, and turnover among NHS and private sector staff caring for people with dementia. BMJ 2001; 322:769–770Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Lawlor B: Managing behavioural and psychological symptoms in dementia. Br J Psychiatry 2000; 181:463–465Crossref, Google Scholar

6. Coen R, Swanwick G, O’Boyle C, Coakley D: Behaviour disturbance and other predictors of caregiver burden in Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1997; 12:331–336Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. O’Donnell B, Drachman D, Barned H: Incontinence and troublesome behavior predict institutionalization in dementia. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 2004; 5:45–52Crossref, Google Scholar

8. Lopez OL, Wisniewski SR, Becker JT, Boller F, DeKosky ST: Psychiatric medication and abnormal behavior as predictors of progression in probable Alzheimer’s disease. Arch Neurol 1999; 56:1266–1272Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Smith DA, Beier MT: Association between risperidone treatment and cerebrovascular adverse events: examining the evidence and postulating hypotheses for an underlying mechanism. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2004; 5:129–132Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Wooltorton E: Risperidone (Risperdal): increased rate of cerebrovascular event in dementia trials. CMAJ 2002; 167:1269–1270Medline, Google Scholar

11. Moher D, Jadad A, Nichol G, Penman M, Tugwell P, Walsh S: Assessing the quality of randomized controlled trials: an annotated bibliography of scales and checklists. Control Clin Trials 1995; 16:62–73Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Brooker D, Duce L: Wellbeing and activity in dementia: a comparison of group reminiscence therapy, structured goal-directed group activity and unstructured time. Aging Ment Health 2000; 4:354–358Crossref, Google Scholar

13. Baines S, Saxby P, Ehlert K: Reality orientation and reminiscence therapy: a controlled cross-over study of elderly confused people. Br J Psychiatry 1987; 151:222–231Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Goldwasser AN, Auerbach SM, Harkins SW: Cognitive, affective, and behavioral effects of reminiscence group therapy on demented elderly. Int J Aging Hum Dev 1987; 25:209–222Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Korb C: The influence of music therapy on patients with a diagnosed dementia. Can J Music Therapy 1997; 5:26–54Google Scholar

16. Haight BK, Bachman DL, Hendrix S, Wagner MT, Meeks A, Johnson J: Life review: treating the dyadic family unit with dementia. Clin Psychol Psychother 2003; 10:165–174Crossref, Google Scholar

17. Babins L: Conceptual analysis of validation therapy. Int J Aging Hum Dev 1988; 26:161–168Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Morton I, Bleathman C: The effectiveness of validation therapy in dementia: a pilot study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1991; 6:327–330Crossref, Google Scholar

19. Toseland RW, Diehl M, Freeman K, Manzanares T, Naleppa M, McCallion P: The impact of validation group therapy on nursing home residents with dementia. J Appl Gerontol 1997; 16:31–50Crossref, Google Scholar

20. Baldelli MV, Piriani A, Motta M, Abati E, Mariani E, Manzi V: Effects of reality orientation therapy on elderly patients in the community. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 1993; 17:211–218Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Brook P, Degun G, Mather M: Reality orientation, a therapy for psychogeriatric patients: a controlled study. Br J Psychiatry 1975; 127:42–45Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Greene JG, Nicol R, Jamieson H: Reality orientation with psychogeriatric patients. Behav Res Ther 1979; 17:615–618Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Greene JG, Timbury GC, Smith R, Gardiner M: Reality orientation with elderly patients in the community: an empirical evaluation. Age Ageing 1983; 12:38–43Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Hanley IG, McGuire RJ, Boyd WD: Reality orientation and dementia: a controlled trial of two approaches. Br J Psychiatry 1981; 138:10–14Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Ishizaki J, Meguro K, Ishii H, Yamaguchi S, Shimada M, Yamadori A, Yambe Y, Yamazaki H: The effects of group work therapy in patients with Alzheimer’s disease (letter). Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2000; 15:532–535Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Johnson CH, McLaren SM, McPherson FM: The comparative effectiveness of three versions of “classroom” reality orientation. Age Ageing 1981; 10:33–35Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Metitieri T, Zanetti O, Geroldi C, Frisoni GB, De Leo D, Dello Buono M, Bianchetti A, Trabucchi M: Reality orientation therapy to delay outcomes of progression in patients with dementia: a retrospective study. Clin Rehabil 2001; 15:471–478Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Reeve W, Ivison D: Use of environmental manipulation and classroom and modified informal reality orientation with institutionalized, confused elderly patients. Age Ageing 1985; 14:119–121Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Panella JJ Jr, Lilliston BA, Brush D, McDowell FH: Day care for dementia patients: an analysis of a four-year program. J Am Geriatr Soc 1984; 32:883–886Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Mitchell LA, Maercklein G: The effect of individualized special instruction on the behaviors of nursing home residents diagnosed with dementia. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 1996; 11:23–31Crossref, Google Scholar

31. Quayhagen MP, Quayhagen M, Corbeil RR, Roth PA, Rodgers JA: A dyadic remediation program for care recipients with dementia. Nurs Res 1995; 44:153–159Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Quayhagen MP, Quayhagen M, Corbeil RR, Hendrix RC, Jackson JE, Snyder L, Bower D: Coping with dementia: evaluation of four nonpharmacologic interventions. Int Psychogeriatr 2000; 12:249–265Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Romero B, Wenz M: Self-maintenance therapy in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychol Rehabil 2001; 11:333–355Crossref, Google Scholar

34. Spector A, Orrell M, Davies S, Woods RT: Can reality orientation be rehabilitated? development and piloting of an evidence-based programme of cognition-based therapies for people with dementia. Neuropsychol Rehabil 2001; 11:377–379Crossref, Google Scholar

35. Spector A, Thorgrimsen L, Woods B, Royan L, Davies S, Butterworth M, Orrell M: Efficacy of an evidence-based cognitive stimulation therapy programme for people with dementia: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry 2003; 183:248–254Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Beck CK, Vogelpohl TS, Rasin JH, Uriri JT, O’Sullivan P, Walls R, Phillips R, Baldwin B: Effects of behavioral interventions on disruptive behavior and affect in demented nursing home residents. Nurs Res 2002; 51:219–228Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Benedict RHB, Shapiro A, Priore R, Miller C, Munschauer F, Jacobs L: Neuropsychological counselling improves social behavior in cognitively-impaired multiple sclerosis patients. Mult Scler 2000; 6:391–396Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. DeYoung S, Just G, Harrison R: Decreasing aggressive, agitated, or disruptive behavior: participation in a behavior management unit. J Gerontol Nurs 2002; 28:22–31Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Hoeffer B, Rader J, McKenzie D, Lavelle M, Stewart B: Reducing aggressive behaviour during bathing cognitively impaired nursing home residents. J Gerontol Nurs 1997; 23:16–23Google Scholar

40. Mishara BL: Geriatric patients who improve in token economy and general milieu treatment programs: a multivariate analysis. J Consult Clin Psychol 1978; 46:1340–1348Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41. Rogers JC, Holm MB, Burgio LD, Granieri E, Hsu C, Hardin JM, McDowell BJ: Improving morning care routines of nursing home residents with dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc 1999; 47:1049–1057Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

42. Suhr J, Anderson S, Tranel D: Progressive muscle relaxation in the management of behavioural disturbance in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychol Rehabil 1999; 9:31–44Crossref, Google Scholar

43. Teri L, Logsdon RG, Uomoto J, McCurry SM: Behavioral treatment of depression in dementia patients: a controlled clinical trial. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 1997; 52:159–166Crossref, Google Scholar

44. Teri L: Behavioral treatment of depression in patients with dementia. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 1994; 8(suppl 3):66–74Google Scholar

45. Welden S, Yesavage JA: Behavioral improvement with relaxation training in senile dementia. Clin Gerontol 1982; 1:45–49Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

46. Alexopoulos P: Management of sexually disinhibited behavior by a dementia patient. Aust J Ageing 1994; 13:119Crossref, Google Scholar

47. Bakke BL, Kvale S, Burns T, McCarten JR, Wilson L, Maddox M, Cleary J: Multicomponent intervention for agitated behavior in a person with Alzheimer’s disease. J Appl Behav Anal 1994; 27:175–176Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

48. Birchmore T, Clague S: A behavioural approach to reduce shouting. Nurs Times 1983; 79:37–39Medline, Google Scholar

49. Bird M, Alexopoulos P, Adamowicz J: Success and failure in 5 case-studies: use of cued-recall to ameliorate behavior problems in senile dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1995; 10:305–311Crossref, Google Scholar

50. Boehm S, Whall AL, Cosgrove KL, Locke JD, Schlenk EA: Behavioral analysis and nursing interventions for reducing disruptive behaviors of patients with dementia. Appl Nurs Res 1995; 8:118–122Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

51. Buchanan JA, Fisher JE: Functional assessment and noncontingent reinforcement in the treatment of disruptive vocalization in elderly dementia patients. J Appl Behav Anal 2002; 35:99–103Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

52. Carpenter B, Ruckdeschel K, Ruckdeschel H, Van Haitsma K: R-E-M psychotherapy: a manualized approach for long-term care residents with depression and dementia. Clin Gerontol 2003; 25:25–49Crossref, Google Scholar

53. Doyle C, Zapparoni T, O’Connor D, Runci S: Efficacy of psychosocial treatments for noisemaking in severe dementia. Int Psychogeriatr 1997; 9:405–422Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

54. Heard K, Watson TS: Reducing wandering by persons with dementia using differential reinforcements. J Appl Behav Anal 1999; 32:381–384Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

55. Jozsvai E, Richards B, Leach L: Behavior management of a patient with Creutzfeldt-Jacob disease. Clin Gerontol 1996; 16:11–17Crossref, Google Scholar

56. Kipling T, Bailey M, Charlesworth G: The feasibility of a cognitive behavioural therapy group for men with mild/moderate cognitive impairment. Behavioural & Cognitive Psychotherapy 1999; 27:189–193Crossref, Google Scholar

57. Koder DA: Treatment of anxiety in the cognitively impaired elderly: can cognitive-behavior therapy help? Int Psychogeriatr 1998; 10:173–182Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

58. Lundervold DA, Jackson T: Use of applied behaviour analysis in treating nursing home residents. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1992; 43:171–173Abstract, Google Scholar

59. Moniz-Cook E, Woods R, Richards K: Functional analysis of challenging behaviour in dementia: the role of superstition. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2001; 16:45–56Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

60. Wisner E, Green M: Treatment of a demented patient’s anger with cognitive-behavioral strategies. Psychol Rep 1986; 59(2, part 1):447–450Google Scholar

61. Bourgeois MS, Burgio LD, Schulz R, Beach S, Palmer B: Modifying repetitive verbalizations of community-dwelling patients with AD. Gerontologist 1997; 37:30–39Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

62. Gormley N, Lyons D, Howard R: Behavioural management of aggression in dementia: a randomized controlled trial. Age Ageing 2001; 30:141–145Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

63. Huang HL, Shyu YI, Chen MC, Chen ST, Lin LC: A pilot study on a home-based caregiver training program for improving caregiver self-efficacy and decreasing the behavioral problems of elders with dementia in Taiwan. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2003; 18:337–345Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

64. Teri L, Uomoto JM: Reducing excess disability in dementia patients: training caregivers to manage patient depression. Clin Gerontol 1991; 10:49–63Crossref, Google Scholar

65. Teri L, Logsdon RG, Peskind E, Raskind M, Weiner MF, Tractenberg RE, Foster NL, Schneider LS, Sano M, Whitehouse P, Tariot P, Mellow AM, Auchus AP, Grundman M, Thomas RG, Schafer K, Thal LJ (Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study): Treatment of agitation in AD: a randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Neurology 2000; 55:1271–1278; correction, 2001; 56:426Google Scholar

66. Teri L, Gibbons L, McCurry SM, Logsdon RG, Buchner DM, Barlow WE, Kukull WA, LaCroix AZ, McCormick W, Larson EB: Exercise plus behavioral management in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2003; 290:2015–2022Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

67. Weiner MF, Tractenberg RE, Sano M, Logsdon R, Teri L, Galasko D, Gamst A, Thomas R, Thal LJ: No long-term effect of behavioral treatment on psychotropic drug use for agitation in Alzheimer’s disease patients. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 2002; 15:95–98Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

68. Burgener SC, Bakas T, Murray C, Dunahee J, Tossey S: Effective caregiving approaches for patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Geriatr Nurs 1998; 19:121–126Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

69. Marriot A, Donaldson C, Tarrier N, Burns A: Effectiveness of cognitive-behavioural family intervention in reducing the burden of care in carers of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Br J Psychiatry 2000; 176:557–562Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

70. Eloniemi-Sulkava U, Notkola IL, Hentinen M, Kivela SL, Sivenius J, Sulkava R: Effects of supporting community-living demented patients and their caregivers: a randomized trial. J Am Geriatr Soc 2001; 49:1282–1287Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

71. Ghatak R: Effects of an intervention program on dementia patients and their caregivers. Caring 1994; 13:34–39Medline, Google Scholar

72. Haupt M, Karger A, Janner M: Improvement of agitation and anxiety in demented patients after psychoeducative group intervention with their caregivers. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2000; 15:1125–1129Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

73. Hebert R, Levesque L, Vezina J, Lavoie JP, Ducharme F, Gendron C, Preville M, Voyer L, Dubois MF: Efficacy of a psychoeducative group program for caregivers of demented persons living at home: a randomized controlled trial. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2003; 58:S58-S67Google Scholar

74. McCallion P, Toseland RW, Freeman K: An evaluation of a family visit education program. J Am Geriatr Soc 1999; 47:203–214Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

75. Droes RM, Breebaart E, Ettema TP, van Tilburg W, Mellenbergh GJ: Effect of integrated family support versus day care only on behavior and mood of patients with dementia. Int Psychogeriatr 2000; 12:99–115Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

76. Ferris SH, Steinberg G, Shulman E, Kahn R, Reisberg B: Institutionalization of Alzheimer’s disease patients: reducing precipitating factors through family counseling. Home Health Care Serv Q 1987; 8:23–51Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

77. Wells DL, Dawson P, Sidani S, Craig D, Pringle D: Effects of an abilities-focused program of morning care on residents who have dementia and on caregivers. J Am Geriatr Soc 2000; 48:442–449Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

78. Mittelman MS, Ferris SH, Shulman E, Steinberg G, Levin B: A family intervention to delay nursing home placement of patients with Alzheimer disease: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 1996; 276:1725–1731Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

79. Woods RT, Wills W, Higginson IJ, Hobbins J, Whitby M: Support in the community for people with dementia and their carers: a comparative outcome study of specialist mental health service interventions. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2003; 18:298–307Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

80. Ashida S: The effect of reminiscence music therapy sessions on changes in depressive symptoms in elderly persons with dementia. J Music Ther 2000; 37:170–182Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

81. Brotons M, PickettCooper PK: The effects of music therapy intervention on agitation behaviors of Alzheimer’s disease patients. J Music Ther 1996; 33:2–18Crossref, Google Scholar

82. Casby JA, Holm MB: The effect of music on repetitive disruptive vocalizations of persons with dementia. Am J Occup Ther 1994; 48:883–889Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

83. Clair AA, Bernstein B: The effect of no music, stimulative background music and sedative background music on agitated behaviours in persons with severe dementia. Activities, Adaptation and Aging 1994; 19:61–70Crossref, Google Scholar

84. Clark ME, Lipe AW, Bilbrey M: Use of music to decrease aggressive behaviors in people with dementia. J Gerontol Nurs 1998; 24:10–17Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

85. Denney A: Quiet music: an intervention for mealtime agitation? J Gerontol Nurs 1997; 23:16–23Google Scholar

86. Fitzgerald-Cloutier ML: The use of music therapy to decrease wandering: an alternative to restraints. Music Therapy Perspectives 1993; 11:32–36Crossref, Google Scholar

87. Gardiner JC, Furois M, Tansley DP, Morgan B: Music therapy and reading as intervention strategies for disruptive behavior in dementia. Clin Gerontol 2000; 22:31–46Crossref, Google Scholar

88. Gaebler HC, Hemsley DR: The assessment and short-term manipulation of affect in the severely demented. Behavioural Psychotherapy 1991; 19:145–156Crossref, Google Scholar

89. Gerdner LA: Effects of individualized versus classical “relaxation” music on the frequency of agitation in elderly persons with Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders. Int Psychogeriatr 2000; 12:49–65Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

90. Gerdner LA, Swanson EA: Effects of individualized music on confused and agitated elderly patients. Arch Psychiatr Nurs 1993; 7:284–291Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

91. Goddaer J, Abraham IL: Effects of relaxing music on agitation during meals among nursing home residents with severe cognitive impairment. Arch Psychiatr Nurs 1994; 8:150–158Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

92. Groene RW: Effectiveness of music therapy, 1: intervention with individuals having senile dementia of the Alzheimer’s type. J Music Therapy 1993; 30:138–157Crossref, Google Scholar

93. Jennings B, Vance D: The short-term effects of music therapy on different types of agitation in adults with Alzheimer’s. Activities, Adaptation and Aging 2002; 26:27–33Crossref, Google Scholar

94. Lindenmuth GF, Patel M, Chang PK: Effects of music on sleep in healthy elderly and subjects with senile dementia of the Alzheimer’s type. Am J Alzheimer’s Care and Related Disorders and Research 1992; 7:13–20Google Scholar

95. Lord TR, Garner JE: Effects of music on Alzheimer patients. Percept Mot Skills 1993; 76:451–455Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

96. Millard KA, Smith JM: The influence of group singing therapy on the behavior of Alzheimer’s disease patients. J Music Therapy 1989; 26:58–70Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

97. Ragneskog H, Brane G, Karlsson I, Kihlgren M: Influence of dinner music on food intake and symptoms common in dementia. Scand J Caring Sci 1996; 10:11–17Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

98. Remington R: Calming music and hand massage with agitated elderly. Nurs Res 2002; 51:317–325Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

99. Runci S, Doyle C, Redman J: An empirical test of language-relevant interventions for dementia. Int Psychogeriatr 1999; 11:301–311Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

100. Sambandham M, Schirm V: Music as a nursing intervention for residents with Alzheimer’s disease in long-term care. Geriatr Nurs 1995; 16:79–83Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

101. Tabloski PA, McKinnon-Howe L, Remington R: Effects of calming music on the level of agitation in cognitively impaired nursing home residents. Am J Alzheimer’s Care and Related Disorders and Research 1995; 10:10–15Google Scholar

102. Thomas DW, Heitman RJ, Alexander T: The effects of music on bathing cooperation for residents with dementia. J Music Therapy 1997; 34:246–259Crossref, Google Scholar

103. Van Diepen E, Baillon SF, Redman J, Rooke N, Spencer DA, Prettyman R: A pilot study of the physiological and behavioural effects of Snoezelen in dementia. Br J Occupational Therapy 2002; 65:61–66Crossref, Google Scholar

104. Baker R, Bell S, Baker E, Gibson S, Holloway J, Pearce R, Dowling Z, Thomas P, Assey J, Wareing LA: A randomized controlled trial of the effects of multi-sensory stimulation (MSS) for people with dementia. Br J Clin Psychol 2001; 40(part 1):81–96Google Scholar

105. Baker R, Dowling Z, Wareing LA, Dawson J, Assey J: Snoezelen: its long-term and short-term effects on older people with dementia. Br J Occupational Therapy 1997; 60:213–218Crossref, Google Scholar

106. Spaull D, Leach C: An evaluation of the effects of sensory stimulation with people who have dementia. Behavioural & Cognitive Psychotherapy 1998; 26:77–86Crossref, Google Scholar

107. Wareing LA, Coleman PG, Baker R: Multisensory environments and older people with dementia. Br J Therapy and Rehabilitation 1998; 5:624–629Crossref, Google Scholar

108. Hope KW: The effects of multisensory environments on older people with dementia. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 1998; 5:377–385Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

109. Burgio L, Scilley K, Hardin JM, Hsu C, Yancey J: Environmental “white noise”: an intervention for verbally agitated nursing home residents. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 1996; 51:364–373Crossref, Google Scholar

110. Kempenaar L, McNamara C, Creaney B: Sensory stimulation work with carers in the community. J Dementia Care 2001; 9:16–17Google Scholar

111. Kim EJ, Buschmann MT: The effect of expressive physical touch on patients with dementia. Int J Nurs Stud 1999; 36:235–243Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

112. Robichaud L, Hebert R, Desrosiers J: Efficacy of a sensory integration program on behaviors of inpatients with dementia. Am J Occup Ther 1994; 48:355–360Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

113. Snyder M, Egan EC, Burns KR: Interventions for decreasing agitation behaviors in persons with dementia. J Gerontol Nurs 1995; 21:34–40Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

114. Young SH, Muir-Nash J, Ninos M: Managing nocturnal wandering behavior. J Gerontol Nurs 1988; 14:7–12Crossref, Google Scholar

115. Whall AL, Black ME, Groh CJ, Yankou DJ, Kupferschmid BJ, Foster NL: The effect of natural environments upon agitation and aggression in late stage dementia patients. Am J Alzheimer Dis 1997; 12:216–220Crossref, Google Scholar

116. Witucki J, Twibell RS: The effect of sensory stimulation activities on the psychological well being of patients with advanced Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Alzheimer Dis 1997; 12:10–15Crossref, Google Scholar

117. Camberg L, Woods P, Ooi WL, Hurley A, Volicer L, Ashley J, Odenheimer G, McIntyre K: Evaluation of simulated presence: a personalized approach to enhance well-being in persons with Alzheimer’s disease. J Am Geriatr Soc 1999; 47:446–452Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

118. Miller S, Vermeersch PE, Bohan K, Renbarger K, Kruep A, Sacre S: Audio presence intervention for decreasing agitation in people with dementia. Geriatr Nurs 2001; 22:66–70Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

119. Woods P, Ashley J: Simulated presence therapy: using selected memories to manage problem behaviors in Alzheimer’s disease patients. Geriatr Nurs 1995; 16:9–14Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

120. Peak JS, Cheston RIL: Using simulated presence therapy with people with dementia. Aging Ment Health 2002; 6:77–81Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

121. Hall L, Hare J: Video respite for cognitively impaired persons in nursing homes. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 1997; 12:117–121Crossref, Google Scholar

122. Buettner LL, Fitzsimmons S: AD-venture program: therapeutic biking for the treatment of depression in long-term care residents with dementia. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 2002; 17:121–127Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

123. Fitzsimmons S, Buettner LL: Therapeutic recreation interventions for need-driven dementia-compromised behaviors in community-dwelling elders. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 2002; 17:367–381Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

124. Ishizaki J, Meguro K, Ohe K, Kimura E, Tsuchiya E, Ishii H, Sekita Y, Yamadori A: Therapeutic psychosocial intervention for elderly subjects with very mild Alzheimer disease in a community: the Tajiri project. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2002; 16:261–269Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

125. Kim NC, Kim HS, Yoo YS, Hahn SW, Yeom HA: Outcomes of day care: a pilot study on changes in cognitive function and agitated behaviors of demented elderly in Korea. Nurs Health Sci 2002; 4:3–7Medline, Google Scholar

126. Martichuski DK, Bell PA, Bradshaw B: Including small group activities in large special care units. Journal of Applied Gerontology 1996; 15:224–237Crossref, Google Scholar

127. Sival RC, Vingerhoets RW, Haffmans PMJ, Jansen PAE, Ton Hazelhoff JN: Effect of a program of diverse activities on disturbed behavior in three severely demented patients. Int Psychogeriatr 1997; 9:423–430Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

128. Snyder M, Tseng Y, Brandt C, Croghan C, Hanson S, Constantine R, Kirby L: A glider swing intervention for people with dementia. Geriatr Nurs 2001; 22:86–90Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

129. Lawton MP, Van Haitsma K, Klapper J, Kleban MH, Katz IR, Corn J: A stimulation-retreat special care unit for elders with dementing illness. Int Psychogeriatr 1998; 10:379–395Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

130. Cleary TA, Clamon C, Price M, Shullaw G: A reduced stimulation unit: effects on patients with Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders. Gerontologist 1988; 28:511–514Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

131. Cott CA, Dawson P, Sidani S, Wells D: The effects of a walking/talking program on communication, ambulation, and functional status in residents with Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2002; 16:81–87Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

132. Gorzelle GJ, Kaiser K, Camp CJ: Montessori-based training makes a difference for home health workers and their clients. Caring 2003; 22:40–42Medline, Google Scholar

133. Hopman-Rock M, Staats PGM, Tak ECPM, Droes R-M: The effects of a psychomotor activation programme for use in groups of cognitively impaired people in homes for the elderly. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1999; 14:633–642Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

134. Holmberg SK: Evaluation of a clinical intervention for wanderers on a geriatric nursing unit. Arch Psychiatr Nurs 1997; 11:21–28Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

135. Meyer DL, Dorbacker B, O’Rourke J, Dowling J, Jacques J, Nicholas M: Effects of a “quiet week” intervention on behavior in an Alzheimer boarding home. Am J Alzheimer’s Care and Related Disorders and Research 1992; 7:2–7Google Scholar

136. Namazi KH, Gwinnup PB, Zadorozny CA: A low intensity exercise/movement program for patients with Alzheimer’s disease: the TEMP-AD protocol. J Aging Phys Act 1994; 2:80–92Crossref, Google Scholar

137. Okawa M, Mishima K, Hishikawa Y, Hozumi S, Hori H, Takahashi K: Circadian rhythm disorders in sleep-waking and body temperature in elderly patients with dementia and their treatment. Sleep 1991; 14:478–485Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

138. Orsulic-Jeras S, Schneider NM, Camp CJ: Special feature: Montessori-based activities for long-term care residents with dementia. Topics in Geriatric Rehabilitation 2000; 16:78–91Crossref, Google Scholar

139. Cohen-Mansfield J, Werner P: The effects of an enhanced environment on nursing home residents who pace. Gerontologist 1998; 38:199–208Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

140. Dickinson JI, McLain-Kark J, Marshall-Baker A: The effects of visual barriers on existing behavior in a dementia care unit. Gerontologist 1995; 35:127–130Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

141. Hanley IG: The use of signposts and active training to modify ward disorientation in elderly patients. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry 1981; 12:241–247Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

142. Hewawasam L: Floor patterns limit wandering of people with Alzheimer’s. Nurs Times 1996; 92:41–44Medline, Google Scholar

143. Hussain RA: Modification of behaviors in dementia via stimulus manipulation. Clin Gerontol 1988; 8:37–43Crossref, Google Scholar

144. Hussain RA, Brown DC: Use of two-dimensional grid patterns to limit hazardous ambulation in demented patients. J Gerontol 1987; 42:558–560Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

145. Kincaid C, Peacock JR: The effect of a wall mural on decreasing four types of door-testing behaviors. J Appl Gerontol 2003; 22:76–88Crossref, Google Scholar

146. Kittur SD, Ruskin P: Environmental modification for treatment of agitation in Alzheimer’s patients. Neurorehabilitation 2001; 12:211–214Google Scholar

147. Mayer R, Darby SJ: Does a mirror deter wandering in demented older people? Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1991; 6:607–609Crossref, Google Scholar

148. Namazi KN, Rosner TT, Calkins MP: Visual barriers to prevent ambulatory Alzheimer’s patients from exiting through an emergency door. Gerontologist 1989; 29:699–702Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

149. Williams R, Reeve W, Ivison D, Kavanagh D: Use of environmental manipulation and modified informal reality orientation with institutionalized, confused elderly subjects: a replication. Age Ageing 1987; 16:315–318Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

150. Chafetz PK: Two-dimensional grid is ineffective against demented patients’ exiting through glass doors. Psychol Aging 1990; 5:146–147Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

151. Annerstedt L: Group-living care: an alternative for the demented elderly. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 1997; 8:136–142Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

152. Annerstedt L: Development and consequences of group living in Sweden: a new mode of care for the demented elderly. Soc Sci Med 1993; 37:1529–1538Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

153. Bianchetti A, Benvenuti P, Ghisla KM, Frisoni GB, Trabucchi M: An Italian model of dementia special care unit: results of a pilot study. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 1997; 11:53–56Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

154. Namazi KH, Johnson BD: Pertinent autonomy for residents with dementias: modification of the physical environment to enhance independence. Am J Alzheimer’s Care and Related Disorders and Research 1992; 7:16–21Google Scholar

155. Wells Y, Jorm AF: Evaluation of a special nursing home unit for dementia sufferers: a randomised controlled comparison with community care. Aust NZ J Psychiatry 1987; 21:524–531Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

156. Wimo A, Adolfsson R, Sandman PO: Care for demented patients in different living conditions: effects on cognitive function, ADL-capacity and behaviour. Scand J Prim Health Care 1995; 13:205–210Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

157. Benson DM, Cameron D, Humbach E, Servino L, Gambert SR: Establishment and impact of a dementia unit within the nursing home. J Am Geriatr Soc 1987; 35:319–323Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

158. Brane G, Karlsson I, Kihlgren M, Norberg A: Integrity-promoting care of demented nursing home patients: psychological and biochemical changes. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1989; 4:165–172Crossref, Google Scholar

159. Cohen-Mansfield J, Werner P, Culpepper WJ, Barkley D: Evaluation of an inservice training program on dementia and wandering. J Gerontol Nurs 1997; 23:40–47Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

160. Edberg A, Hallberg IR: Actions seen as demanding in patients with severe dementia during one year of intervention: a comparison with controls. Int J Nursing Stud 2001; 38:271–285Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

161. Hagen BF, Sayers D: When caring leaves bruises: the effects of staff education on resident aggression. J Gerontol Nurs 1995; 21:7–16Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

162. Matthews EA, Farrell GA, Blackmore AM: Effects of an environmental manipulation emphasizing client-centred care on agitation and sleep in dementia sufferers in a nursing home. J Adv Nurs 1996; 24:439–447Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

163. McCallion P, Toseland RW, Lacey D, Banks S: Educating nursing assistants to communicate more effectively with nursing home residents with dementia. Gerontologist 1999; 39:546–558Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

164. Schrijnemaekers V, van Rossum E, Candel M, Frederiks C, Derix M, Sielhorst H, van den Brandt P: Effects of emotion-oriented care on elderly people with cognitive impairment and behavioral problems. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2002; 17:926–937Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

165. Testad I, Aarsland AM, Aasland D: The effect of staff training on the use of restraint in dementia: a single-blind randomised controlled trial. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2005; 20:587–590Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

166. Annerstedt L, Sanada J, Gustafson L: A dynamic long-term care system for the demented elderly. Int Psychogeriatr 1996; 8:561–574Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

167. Bellelli G, Frisoni GB, Bianchetti A, Boffelli S, Guerrini GB, Scotuzzi A, Ranieri P, Ritondale G, Guglielmi L, Fusari A, Raggi G, Gasparotti A, Gheza A, Nobili G, Trabucchi M: Special care units for demented patients: a multicenter study. Gerontologist 1998; 38:456–462Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

168. Chafetz PK: Behavioral and cognitive outcomes of SCU care. Clin Gerontol 1991; 11:19–38Crossref, Google Scholar

169. Frisoni GB, Gozzetti A, Bignamini V, Vellas BJ, Berger AK, Bianchetti A, Rozzini R, Trabucchi M: Special care units for dementia in nursing homes: a controlled study of effectiveness. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 1998; 26(suppl 1):215–224Google Scholar

170. Kovach CR, Stearns SA: DSCUs: a study of behavior before and after residence. J Gerontol Nurs 1994; 20:33–41Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

171. Morgan DG, Stewart NJ: High versus low density special care units: impact on the behaviour of elderly residents with dementia. Can J Aging 1998; 17:143–165Crossref, Google Scholar

172. Warren S, Janzen W, Andiel-Hett C, Liu L, McKim HR, Schalm C: Innovative dementia care: functional status over time of persons with Alzheimer disease in a residential care centre compared to special care units. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2001; 12:340–347Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

173. Webber P, Breuer W, Lindeman D: Alzheimer’s special care units vs integrated nursing homes: a comparison of resident outcomes. J Clin Geropsychol 1995; 1:189–205Google Scholar