Clozapine Augmented With Risperidone in the Treatment of Schizophrenia: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The authors evaluated the efficacy and safety of augmenting clozapine with risperidone in patients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia. METHOD: In a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled 12-week trial, 40 patients unresponsive or partially responsive to clozapine monotherapy received a steady dose of clozapine combined with either placebo (N=20) or up to 6 mg/day of risperidone (N=20). Patient psychopathology was assessed at 2-week intervals with the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) and the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS), among other measures. Movement disorders were assessed with the Simpson-Angus Rating Scale. RESULTS: From baseline to week 6 and week 12, mean BPRS total and positive symptom subscale scores were reduced significantly in both groups, but the reductions were significantly greater with clozapine/risperidone treatment. Reductions in SANS scores were also significantly greater with clozapine/risperidone treatment than with clozapine/placebo. The adverse event profile for clozapine/risperidone treatment was similar to that for clozapine/placebo. Simpson-Angus Rating Scale scores were lower with clozapine/risperidone treatment throughout the trial but increased to approach those of clozapine/placebo treatment at week 12. Clozapine/risperidone treatment did not induce additional weight gain, agranulocytosis, or seizures compared with clozapine/placebo treatment. CONCLUSIONS: In patients with a suboptimal response to clozapine, the addition of risperidone improved overall symptoms and positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia. The combination appears to be safe and well tolerated. Augmentation of clozapine with risperidone may provide additional clinical benefit for patients who are nonresponsive or only partially responsive to clozapine alone.

The landmark study by Kane et al. (1) established clozapine as the treatment of choice for severely ill patients with schizophrenia whose psychotic symptoms are refractory to conventional antipsychotic treatment. In the Kane study, 30% of patients with refractory symptoms responded to treatment with clozapine. That finding led to renewed interest in clozapine and an optimistic outlook regarding improved treatment for severely ill psychotic patients. Meltzer (2) reported in an uncontrolled study that 6 months of clozapine treatment yielded a good clinical response in 50% of patients whose symptoms had previously been refractory.

However, a considerable number of patients treated with clozapine are still nonresponsive or only partially responsive. For example, in a double-blind comparative study, Rosenheck et al. (3) reported a lower response rate with clozapine than that reported by either Kane et al. (1) or Meltzer (2) and that the drug was only slightly better than the conventional antipsychotic haloperidol. A double-blind study by Simpson et al. (4) compared three clozapine doses (100, 300, and 600 mg/day) in sequential 16-week randomized crossover phases. Although higher clozapine doses were associated with a greater reduction in symptom severity, overall efficacy was disappointing: only five of 50 patients were judged to be responsive. In a meta-analysis, Wahlbeck et al. (5) found that clozapine was superior to conventional antipsychotics in controlling symptoms in patients with refractory schizophrenia, but only one-third of patients met the criteria for a clinically meaningful treatment response. According to a review of data from clozapine clinical trials by Buckley et al. (6), about half of patients with symptoms refractory to other antipsychotic agents are also nonresponsive to clozapine. These authors estimate that some 325,000 patients in the United States with refractory schizophrenia spectrum disorders are also nonresponsive to clozapine or would be if offered this treatment.

There is little evidence to guide the next treatment steps for patients who do not respond to clozapine monotherapy at recommended doses. To improve response rates, U.S. psychiatrists began to administer clozapine in doses higher than those administered by European psychiatrists, but higher doses did not appear to improve efficacy (7). Others reasoned that the efficacy of clozapine, an agent with broad-spectrum receptor activity but relatively weak dopamine D2-antagonist properties, might be enhanced by augmentation with an antipsychotic that provides high-potency D2 blockade (8).

A limited number of published case reports and small studies have reported the effects of clozapine augmentation with other antipsychotics. Sulpiride, a relatively selective D2 antagonist, showed promise in a placebo-controlled clozapine augmentation trial (9). In this study, eight of 16 patients treated with clozapine and sulpiride, compared with only one of 12 patients given clozapine and placebo, demonstrated a score reduction of 20% or more on the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS). However, in a controlled trial conducted in China, clozapine augmentation with chlorpromazine was not superior to clozapine monotherapy (10). Case reports and a small patient series have suggested promise for clozapine augmentation with loxapine (11), pimozide (12), and olanzapine (13), but rigorous trials of these agents have not been conducted.

Risperidone is, to date, the most extensively documented clozapine augmentation agent. Compared with clozapine, risperidone has greater affinity for D2 and serotonin 5-HT2 receptors. Multiple case reports (14–18) have described a benefit from clozapine augmentation with risperidone, but several others (reviewed by Chong and Remington [19]) have reported negative results. Of greater interest are three uncontrolled prospective treatment studies in larger series of patients. In the first study (20), 12 patients with psychotic symptoms previously refractory to clozapine monotherapy received open-label clozapine augmented with risperidone for 4 weeks. By the end of the trial, 10 of the patients exhibited a 20% or greater reduction in BPRS total scores. In the second study (21), a 12-week trial, seven of 13 patients with symptoms refractory to clozapine demonstrated a 20% or greater reduction in total scores on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale, and four were rated as “much improved” on the Clinical Global Impression (CGI) improvement scale. In contrast, the results of the third trial showed that none of the 12 patients whose symptoms were refractory to clozapine exhibited a response (20% reduction in the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale total score) after they had received 4 weeks of combined treatment with clozapine and risperidone (22).

Although augmentation strategies are poorly documented, they are fairly common in clinical practice, with perhaps one-sixth of patients with psychosis in the United States receiving more than one antipsychotic drug (23, 24). Understandably, this situation has caused some concern (25–28). In addition to their poorly documented efficacy, polypharmacy regimens pose certain risks, including pharmacokinetic interactions, increased risk of adverse events, and, at least theoretically, loss of “atypicality” resulting from higher overall drug exposure, leading to greater liability for tardive dyskinesia. Complex drug regimens can also compromise patient compliance with treatment, and their benefit may not justify their costs. Given the substantial public health burden of clozapine-refractory schizophrenia and the prevalent use of augmentation strategies, rigorous investigation of these strategies is of utmost importance. To that end, we conducted a 12-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the efficacy and safety of clozapine augmented with risperidone in a well-defined group of patients with schizophrenia refractory to clozapine monotherapy.

Method

Patients

Inpatients or outpatients who continued to experience significant psychotic symptoms despite adequate treatment with clozapine were eligible to participate in this trial. Study participants were recruited from a large population of state hospital inpatients and recently discharged patients living in highly structured community settings. Thorough records of psychiatric history and prior antipsychotic drug therapy were available for all patients. Patients were included if they 1) had a DSM-IV diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder; 2) were 20–65 years of age; 3) had, before treatment with clozapine, documented treatment failure after two antipsychotics approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration were administered for an adequate duration in a sufficient dose (6 or more weeks of 1000 mg/day of chlorpromazine equivalents); 4) demonstrated a documented failure to show a satisfactory clinical response to an adequate trial of clozapine (3 or more months of at least 600 mg/day of oral clozapine or a plasma drug level of 350 ng/ml or higher); and 5) had persistent psychotic symptoms, as evidenced by either a total score of at least 45 on the BPRS (on which each of 18 items is scored from 1 to 7) or a rating of moderately ill (4 or more) on at least two of the four BPRS positive symptom items (hallucinatory behavior, conceptual disorganization, unusual thought content, and suspiciousness).

Study Procedures

All patients were fully informed about the benefits, risks, and potential adverse effects involved in participating in this study and signed an informed consent document. They continued to be treated by their primary psychiatrist, who also signed the informed consent. Patients remained in their current living arrangements without any study-related modifications to their daily routines beyond regularly scheduled clinical rating sessions.

A 4-week baseline evaluation and clozapine run-in phase was followed by 12 weeks of placebo-controlled augmentation with risperidone. To initiate the baseline observation period, all patients had to have remained on a stable dose of clozapine for at least 4 weeks. Baseline doses of clozapine were established by treating psychiatrists and remained stable throughout the study. After the run-in period, patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to augmentation with risperidone or matching placebo. Risperidone was started at 1 mg/day, with planned increases to 1 or 2 mg/day on day 4, to 2 or 3 mg/day on day 8, to 4 mg/day on day 21, and to 6 mg/day on day 22. Each patient’s study medication dose was managed by a nonblinded research fellow not involved in any aspect of patient care who acted as intermediary between the study investigators, treating psychiatrist, and pharmacy. The raters, treating psychiatrist, and patient remained blinded throughout the study. At each weekly clinic visit, the treating psychiatrist could instruct the research fellow to either continue or increase the current dose of blinded study medication. Patients judged by their treating psychiatrist to be unable to tolerate the dose escalation schedule because of adverse effects (other than clinical symptoms of schizophrenia) were maintained at their maximum tolerated dose for the remainder of the study.

Patient Assessments

Biweekly systematic evaluations of psychopathology and adverse events were initiated during the 4-week baseline observation period and continued throughout the 12-week randomized treatment phase. These assessments were performed primarily by two senior research fellows, blinded to treatment assignment and not directly involved in patient care. Raters evaluated the same patients throughout the study period; however, a third “back-up” rater was available for times of planned vacations and illness. All three raters took part in regularly scheduled (at least monthly) practice ratings with other patients or videotaped interviews to maintain consistency and to identify any “idiosyncratic” approaches that developed over time.

Efficacy evaluations included the BPRS (29), CGI (30), and Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS) (31). Movement disorders were assessed at 2-week intervals with the Simpson-Angus Rating Scale (32). A full biochemistry test panel, urinalysis, and hematologic studies were obtained before randomization and at the end of the study. Weekly safety and tolerability evaluations included white blood cell counts, temperature, blood pressure, heart rate, and respiration as well as subjective symptoms.

Statistical Analysis

The primary objective was to test the hypothesis of differential clinical efficacy between the two treatment groups: clozapine with placebo and clozapine with risperidone. The a priori planned comparisons used between-group repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) (SPSS 9.0 for Windows, general linear model, SPSS, Inc., Chicago) with group (the two treatment groups) and time (baseline, week 6, and week 12) as main effects. The ANOVA model also included a group-by-time interaction term. The specific two-group efficacy comparisons across time were BPRS total score, BPRS positive symptom score (sum of BPRS hallucinatory behavior, conceptual disorganization, unusual thought content, and suspiciousness), and negative symptom score (sum of global SANS ratings).

Between-group differences on the safety evaluation were determined by using a repeated-measures ANOVA model when appropriate; otherwise, the unmatched t test and chi-square comparisons were performed. Exploratory analyses were performed by using an analysis of covariance model on the efficacy and safety endpoints to examine the influence of age, duration of illness, and dose and duration of clozapine therapy used throughout the study.

All significance tests were performed by using two-tailed probabilities with an alpha level of 0.05.

Results

Forty patients with persistent psychotic symptoms entered the trial and were randomly assigned in equal numbers to receive clozapine combined with either risperidone or placebo. Background characteristics of the two groups were similar (Table 1). The initial clozapine dose was significantly higher and the initial SANS score somewhat lower, although not reaching significance, in the clozapine/risperidone group than the clozapine/placebo group. In general, all patients had severe refractory symptoms that had affected their lives for an average of more than 20 years. They had not responded to at least two and in some cases six or more different antipsychotic drugs. Nine had not responded to a trial of risperidone. Moreover, as required for study entry, they had continued to manifest substantial psychotic symptoms despite having received optimal treatment with clozapine as monotherapy, and their BPRS, CGI, and SANS scores indicated considerable psychopathology. The duration of prior clozapine treatment ranged from 30 to 584 weeks (mean=396.9, SD=174.4), and two patients had received doses as high as 900 mg/day.

All patients completed 12 weeks of treatment in their randomly assigned group. Mean doses of risperidone were 4.1 mg/day (SD=1.4) at week 6 and 4.43 mg/day (SD=1.5) at week 12. Only eight patients received the maximum 6 mg/day dose of risperidone. Of those, two experienced acute akathisia and required dose reduction.

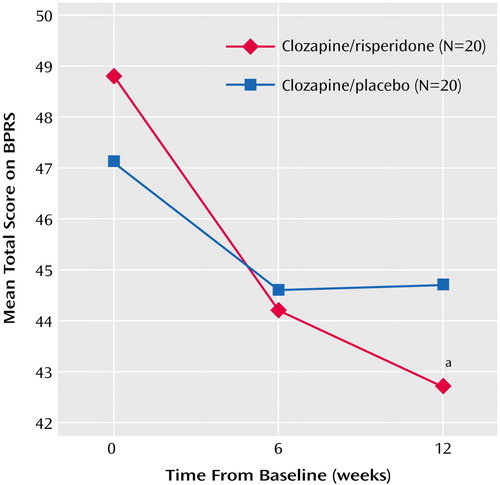

Efficacy

By the end of the 12-week treatment period, a treatment response (20% or greater reduction in BPRS total score) was achieved by seven (35%) of the 20 patients in the clozapine/risperidone group and by two (10%) of the 20 patients in the clozapine/placebo group (χ2=25, df=1, p<0.01). As seen in Figure 1, the BPRS total scores decreased significantly from baseline to week 12 in both treatment groups (main effect for time: F=7.8, df=2, 76, p<0.0001), with a significant group-by-time interaction reflecting a greater score reduction with clozapine/risperidone treatment (F=3.73, df=2, 76, p<0.04). Score reductions from baseline to week 6 were similar in the two groups but were greater with clozapine/risperidone treatment from week 6 to week 12. To determine whether the initial baseline differences contributed to the between-group difference, an analysis of covariance was performed using the baseline BPRS total score as the covariate. With the effects of the baseline differences removed (main covariate between patients effect: F=258.8, df=1, 37, p<0.0001), the main effect of time was no longer significant (F=0.338, df=2, 74, p>0.05). However, the between-group difference at endpoint remained significant (Figure 1).

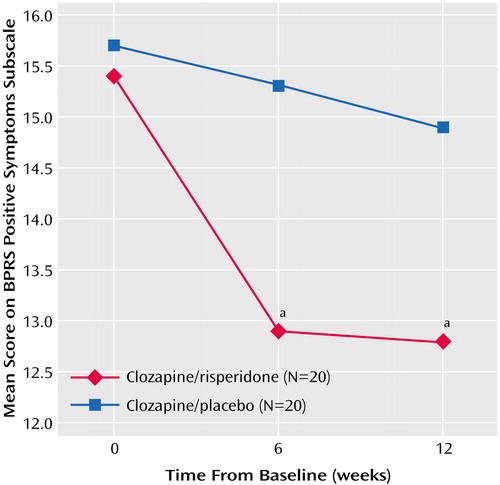

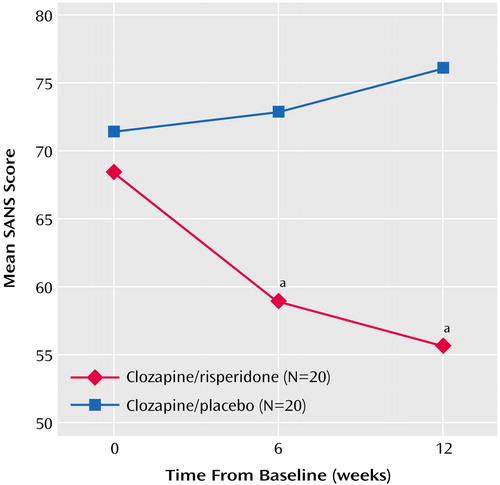

As seen in Figure 2, scores on the BPRS positive symptom subscale decreased significantly from baseline to week 12 in both groups (main effect for time: F=8.3, df=2, 76, p<0.001), but the group-by-time interaction reflected a significantly greater score reduction with clozapine/risperidone treatment than with clozapine/placebo (Figure 2). Negative symptoms (SANS scores) decreased significantly from baseline to week 12 with clozapine/risperidone treatment (main effect for time: F=4.46, df=2, 76, p<0.04), and the between-group difference was significant (Figure 3).

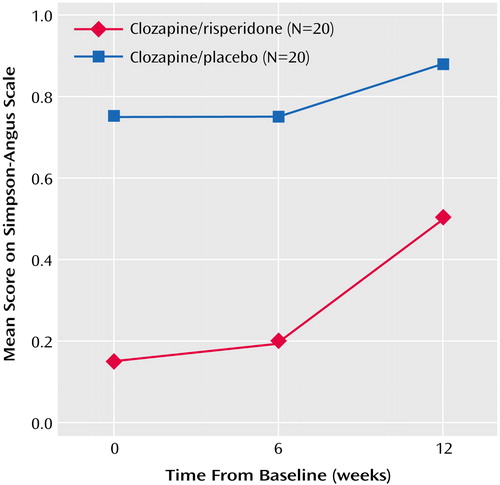

Safety and Tolerability

In general, double-blind augmentation treatment was well tolerated. Both treatment groups had mean initial Simpson-Angus Rating Scale scores below 1.0, indicating minimal severity of movement disorders. The Simpson-Angus Rating Scale scores were lower with clozapine/risperidone treatment throughout the trial, although they increased to approach those of clozapine/placebo treatment by week 12 (Figure 4). The frequency of other adverse events such as weight gain, agranulocytosis, and seizures did not differ between groups.

Plasma clozapine levels did not increase significantly during augmentation treatment, and no changes were observed in white blood cell counts. Absolute neutrophil counts were comparable in the two groups at baseline but significantly higher with clozapine/risperidone treatment at both treatment time points.

Discussion

The efficacy of clozapine augmented with risperidone was superior to that of clozapine combined with placebo in this randomized, double-blind trial in 40 patients with schizophrenia unresponsive to clozapine monotherapy. The beneficial effect of clozapine/risperidone treatment was observed in the mean BPRS total scores and even more prominently in the BPRS positive symptom subscale scores. In addition, negative symptom scores on the SANS improved significantly with clozapine/risperidone treatment relative to clozapine/placebo treatment. Except for mild akathisia, which was observed in two patients and corrected through dose adjustment, risperidone augmentation was not associated with any additional adverse effects and was well tolerated.

To date, only a few controlled trials have evaluated clozapine augmented with an antipsychotic agent of any type, and to our knowledge, this is the first randomized controlled trial involving clozapine augmented with an atypical antipsychotic. Previous trials of this combination include case reports and three open-label, uncontrolled prospective studies that used standardized rating criteria, all involving an approximate total of 50 patients. Inconsistencies in the results of these earlier trials may be attributed to several factors beyond the tendency of small, uncontrolled studies to produce unconfirmed results. The studies differed in the patients’ baseline severity of schizophrenia (two studies focused on outpatients and one on inpatients), prior exposure to risperidone monotherapy (a requirement in one study, undocumented in two studies), duration of augmentation treatment (4 weeks versus 12 weeks), and measures of treatment outcome (BPRS in one study, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale in two studies). Taken together, the results of these studies suggest that perhaps half of patients whose symptoms are refractory to clozapine respond to risperidone augmentation. Our finding of a significant treatment-by-time interaction suggests that studies based on a short (i.e., 4-week) period of observation are likely to produce unreliable results.

Although the double-blind design of our investigation is stronger than that of the others, several methodologic issues raised by Freudenreich and Goff (8), Stern et al. (33), and others must be kept in mind. It is uncertain whether our study is sufficiently powered to identify treatment effects of as yet uncertain magnitude. In one cautionary report, Stern et al. (33) reviewed 13 published trials of antipsychotic augmentation and reported that the likelihood of finding a positive result by chance was 63%. These authors concluded that augmentation trials require 40 to 100 patients, depending on the number and variability of outcome measures and effect size, and our investigation is at the lowest range of acceptable limits. Our study avoided the pitfall of evaluating too many treatment outcomes in relation to the sample size, which could lead to chance findings of statistically significant differences. Nevertheless, our findings must be regarded as preliminary. Although random assignment and blinding are important strengths of our study, definitive conclusions about the efficacy of clozapine combined with risperidone must await future studies with larger sample sizes.

A second important issue relates to the cause of the improvement we observed. If a patient is observed to improve after risperidone is added to his or her clozapine therapy, it cannot be assumed that the effect of clozapine is augmented by risperidone. A substantial improvement occurred over time in both treatment groups, possibly due to patients’ participation in the study and the benefits of weekly clinic visits. On the other hand, this improvement could have been an artifact of the fluctuating course of schizophrenia and the tendency of extreme observations to regress toward the mean over time. However, our patients did seem stable in their lack of clozapine responsivity, as evidenced by the fact that all had received optimal clozapine monotherapy for a considerable time (mean=396.9 weeks, SD=174.4). The improvement associated with risperidone was significantly greater than that seen with placebo, but the observed treatment effect could be due to risperidone alone rather than to the combination. This cannot be completely ruled out with our patient sample; however, nine of the 20 patients in the risperidone augmentation group were unresponsive to prior risperidone monotherapy, and of these nine unresponsive patients, four responded to the combination of clozapine and risperidone. The improvement associated with risperidone could also have been due to the fact that this randomly assigned group entered the study receiving a higher dose of clozapine (528.8 mg versus 402.5 mg). These higher doses of clozapine, acting throughout the course of the study, might account for the significant pattern of effects, although the group mean duration of clozapine treatment was more than 7 years and raises the question of what might cause a treatment effect after such an extensive treatment duration.

The risks of antipsychotic polypharmacy have not been well studied, and information about long-term risks is particularly sparse. Isolated case reports of agranulocytosis associated with the combination of clozapine and risperidone have been reported (34), as well as a pharmacokinetic interaction between the two agents (35). In one study, 20 patients who received clozapine augmented with risperidone had modestly higher serum prolactin levels than did a group receiving clozapine monotherapy (36).

We did not observe an effect of risperidone on serum clozapine levels, nor was such an effect seen in the two open-label studies in which clozapine levels were measured (20, 22). A theoretical concern is that the addition of a potent dopamine D2 receptor blocker to an atypical agent may jeopardize the atypicality of the agent, increasing the risk of movement disorders and tardive dyskinesia. This phenomenon has been observed, although infrequently, with the combination of an atypical and a conventional antipsychotic (8); the implications for combining with atypical agents are unknown. Future studies of antipsychotic combinations should include long-term observation of patients for potential toxic effects, particularly hematologic effects, movement disorders, and tardive dyskinesia.

Our observations, although preliminary, suggest that augmentation with risperidone may benefit patients who are partially responsive or nonresponsive to clozapine monotherapy. Our study population represents both inpatients and those who have recovered sufficiently to live in sheltered community settings, but it is not clear whether our results can be equally generalized to both types of patients. Clozapine augmentation with risperidone appears to be well tolerated and safe, at least for 12 weeks of treatment, but clinicians should approach this augmentation strategy with caution because polypharmacy is associated with potential risks that have not been systematically studied in prospective trials. Additional larger controlled trials are required before firm clinical recommendations can be made about clozapine augmentation strategies. Moreover, in an age in which neurocognitive and functional state measures are becoming central to the discussion of clinical efficacy and effectiveness, a comprehensive assessment that extends beyond psychopathology and side effects would be a welcome addition to the existing literature.

|

Presented in part at the 42nd annual meeting of the New Clinical Drug Evaluation Unit, Boca Raton, Fla., June 10–13, 2002; and at the ninth International Congress on Schizophrenia Research, Colorado Springs, Colo., March 29–April 2, 2003. Received Sept. 5, 2003; revision received Jan. 13, 2004; accepted Feb. 4, 2004. From the Arthur P. Noyes Research Foundation; the Department of Psychiatry, Drexel University College of Medicine, Philadelphia; the Department of Psychiatry, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia; and the Department of Psychiatry, Norristown State Hospital, Norristown, Pa. Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. Josiassen, The Arthur P. Noyes Research Foundation, Norristown State Hospital, 1001 Sterigere St., Norristown, PA 19401; [email protected] (e-mail). This study was funded by Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development.

Figure 1. BPRS Total Scores Over the Study Period for 40 Patients With Refractory Schizophrenia Randomly Assigned to 12 Weeks of Double-Blind Treatment With Clozapine Augmented With Either Risperidone or Placebo

aSignificantly different from the score at 12 weeks for clozapine/placebo treatment per ANCOVA with baseline BPRS total score as the covariate (F=3.15, df=2, 74, p<0.05).

Figure 2. BPRS Positive Symptom Subscale Scores Over the Study Period for 40 Patients With Refractory Schizophrenia Randomly Assigned to 12 Weeks of Double-Blind Treatment With Clozapine Augmented With Either Risperidone or Placebo

aSignificantly greater score reduction at 6 and 12 weeks relative to clozapine/placebo treatment per ANOVA (group-by-time interaction: F=3.18, df=2, 76, p<0.05).

Figure 3. SANS Scores Over the Study Period for 40 Patients With Refractory Schizophrenia Randomly Assigned to 12 Weeks of Double-Blind Treatment With Clozapine Augmented With Either Risperidone or Placebo

aSignificantly greater score reduction at 6 and 12 weeks relative to clozapine/placebo treatment per ANOVA (main effect for group: F=4.08, df=2, 76, p<0.05).

Figure 4. Simpson-Angus Scale Scores Over the Study Period for 40 Patients With Refractory Schizophrenia Randomly Assigned to 12 Weeks of Double-Blind Treatment With Clozapine Augmented With Either Risperidone or Placebo

1. Kane J, Honigfeld G, Singer J, Meltzer H (Clozaril Collaborative Study Group): Clozapine for the treatment-resistant schizophrenic: a double-blind comparison with chlorpromazine. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988; 45:789–796Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Meltzer HY: Duration of a clozapine trial in neuroleptic resistant schizophrenia (letter). Arch Gen Psychiatry 1989; 46:672Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Rosenheck R, Cramer J, Xu W, Thomas J, Henderson W, Frisman L, Fye C, Charney D: A comparison of clozapine and haloperidol in hospitalized patients with refractory schizophrenia. N Engl J Med 1997; 337:809–815Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Simpson GM, Josiassen RC, Stanilla JK, de Leon J, Nair C, Abraham G, Odom-White A, Turner RM: A double-blind study of clozapine dose response in chronic schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:1744–1750; correction, 2001; 158:834Google Scholar

5. Wahlbeck K, Cheine M, Essali A, Adams C: Evidence of clozapine’s effectiveness in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:990–999Abstract, Google Scholar

6. Buckley P, Miller A, Olsen J, Garver D, Miller DD, Csernansky J: When symptoms persist: clozapine augmentation strategies. Schizophr Bull 2001; 27:615–628Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Pollack S, Lieberman JA, Fleischhacker WW, Borenstein M, Safferman AZ, Hummer M, Kurz M: A comparison of European and American dosing regimens of schizophrenic patients on clozapine: efficacy and side effects. Psychopharmacol Bull 1995; 31:315–320Medline, Google Scholar

8. Freudenreich O, Goff DC: Antipsychotic combination therapy in schizophrenia: a review of efficacy and risks of current combinations. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2002; 106:323–330Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Shiloh R, Zemishlany Z, Aizenberg D, Radwan M, Schwartz B, Dorfman-Etrog P, Modai I, Khaikin M, Weizman A: Sulpiride augmentation in people with schizophrenia partially responsive to clozapine: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Br J Psychiatry 1997; 171:569–573Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Potter WZ, Ko GN, Zhang LD, Yan W: Clozapine in China: a review and preview of US/PRC collaboration. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1989; 99:S87-S97Google Scholar

11. Mowerman S, Siris SG: Adjunctive loxapine in a clozapine-resistant cohort of schizophrenic patients. Ann Clin Psychiatry 1996; 8:193–197Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Friedman J, Ault K, Powchik P: Pimozide augmentation for the treatment of schizophrenic patients who are partial responders to clozapine. Biol Psychiatry 1997; 42:522–523Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Gupta S, Sonnenberg SJ, Frank B: Olanzapine augmentation of clozapine. Ann Clin Psychiatry 1998; 10:113–115Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Adesanya A, Pantelis C: Adjunctive risperidone treatment in patients with “clozapine-resistant schizophrenia.” Aust NZ J Psychiatry 2000; 34:533–534Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. McCarthy RH, Terkelsen KG: Risperidone augmentation of clozapine. Pharmacology 1995; 28:61–63Google Scholar

16. Morera AL, Barreiro P, Cano-Munoz JL: Risperidone and clozapine combination for the treatment of refractory schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1999; 99:305–307Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Raju Kumar R, Khanna S: Clozapine-risperidone combination in treatment-resistant schizophrenia (letter). Aust NZ J Psychiatry 2001; 35:543Google Scholar

18. Raskin S, Katz G, Zislin Z, Knobler HY, Durst R: Clozapine and risperidone: combination/augmentation treatment of refractory schizophrenia: a preliminary observation. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2000; 101:334–336Medline, Google Scholar

19. Chong SA, Remington G: Clozapine augmentation: safety and efficacy. Schizophr Bull 2000; 26:421–440Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Henderson DC, Goff DC: Risperidone as an adjunct to clozapine therapy in chronic schizophrenics. J Clin Psychiatry 1996; 57:395–397Medline, Google Scholar

21. Taylor CG, Flynn SW, Altman S, Ehmann T, MacEwan GW, Honer WG: An open trial of risperidone augmentation of partial response to clozapine. Schizophr Res 2001; 48:155–158Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. De Groot IW, Heck AH, van Harten PN: Addition of risperidone to clozapine therapy in chronically psychotic inpatients (letter). J Clin Psychiatry 2001; 62:129–130Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Wang PS, West JC, Tanielian T, Pincus HA: Recent patterns and predictors of antipsychotic medication regimens used to treat schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders. Schizophr Bull 2000; 26:451–457Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Weissman EM: Antipsychotic prescribing practices in the Veterans Healthcare Administration—New York Metropolitan region. Schizophr Bull 2002; 28:31–42Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Marder SR: Can clinical practice guide a research agenda? Schizophr Bull 2002; 28:127–129Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Miller AL, Craig CS: Combination antipsychotics: pros, cons, and questions. Schizophr Bull 2002; 28:105–109Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Stahl SM: Antipsychotic polypharmacy, part 1: therapeutic option or dirty little secret? J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 60:425–426Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Stahl SM: Antipsychotic polypharmacy: squandering precious resources? J Clin Psychiatry 2002; 63:93–94Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Woerner MG, Mennuzza S, Kane JM: Anchoring the BPRS-A: an aid to improved reliability. Psychopharmacol Bull 1988; 24:112–117Medline, Google Scholar

30. Guy W (ed): ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology: Publication ADM 76–338. Washington, DC, US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, 1976, pp 218–222Google Scholar

31. Andreasen NC: Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS). Iowa City, University of Iowa, 1981Google Scholar

32. Simpson GM, Angus JWS: A rating scale for extrapyramidal side effects. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 1970; 212:11–19Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Stern RG, Schmeidler J, Davidson M: Limitations of controlled augmentation trials in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry 1997; 42:138–143Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Godleski LS, Sernyak MJ: Agranulocytosis after addition of risperidone to clozapine treatment (letter). Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:735–736Medline, Google Scholar

35. Tyson SC, Devane CL, Risch SC: Pharmacokinetic interaction between risperidone and clozapine (letter). Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:1401–1402Medline, Google Scholar

36. Henderson DC, Goff DC, Connolly CE, Borba CP, Hayden D: Risperidone added to clozapine: impact on serum prolactin levels. J Clin Psychiatry 2001; 62:605–608Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar