Factors Contributing to Therapists’ Distress After the Suicide of a Patient

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Factors contributing to therapists’ severe distress after the suicide of a patient were investigated. METHOD: Therapists for 34 patients who died by suicide completed a semistructured questionnaire about their reactions, wrote case narratives, and participated in a workshop. RESULTS: Thirteen of the 34 therapists were severely distressed. Four factors were identified as sources of severe distress: failure to hospitalize an imminently suicidal patient who then died, a treatment decision the therapist felt contributed to the suicide, negative reactions from the therapist’s institution, and fear of a lawsuit by the patient’s relatives. Although one emotion was sometimes dominant in the therapist’s response to the suicide, severely distressed therapists, compared to others, reported a significantly larger number of intense emotional states. CONCLUSIONS: Over one-third of therapists who experienced a patient’s suicide were found to suffer severe distress, pointing to the need for further study of the long-term effects of patient suicide on professional practice.

National surveys conducted in the late 1980s indicated that about one-half of psychiatrists and one-quarter of psychologists had experienced the suicide of a patient (1, 2). These surveys found younger, less experienced clinicians to be especially affected by the experience, and studies of patient suicide in psychiatric residency programs (3–5) confirm this finding.

Our earlier work (6) and that of others (7–15) show that clinicians resemble family members and friends in experiencing shock, grief, guilt, and anger after a patient’s suicide. Although virtually all these studies showed that some therapists become more distressed than others, we know of no systematic investigation to specify which emotional responses distinguish severely distressed therapists from others. We also have found no studies relating therapist distress to situational factors pertaining to the patient’s suicide.

In this report we present findings from an ongoing study of therapists that illuminate why some respond more intensely than others to a patient suicide.

Method

To date, 34 participant therapists, 25 male and nine female, have been enrolled in the study through a variety of sources, including notices in psychiatric publications and mailings to lists of psychiatric association members. Several participant therapists were referred to the study by relatives of patients who died by suicide. Twenty-eight participants were psychiatrists, five were psychologists, and one was a psychiatric social worker. Fifteen therapists had treated the patient in private practice, and 19 had treated the patient in an institutional setting. Nine (26.5%) had been in practice for 15 or more years, seven (20.6%) for 10–14 years, nine (26.5%) for 5–9 years, and nine (26.5%) for less than 5 years. Seven therapists in the last category—four psychiatrists and three psychologists—were still in training when the suicide occurred.

The principal investigators (H.H., A.P.H., J.T.M., K.S., H.R.) fully explained all project procedures to the 34 participants and obtained their informed consent. In addition to completing several semistructured questionnaires about the patient and preparing a detailed patient case narrative, each therapist completed a therapist reaction questionnaire that contained both open-ended and structured items. The therapists rated nine emotional reactions—shock, grief, guilt, sense of inadequacy, anger, anxiety, betrayal, shame or embarrassment, and depression—on an ordinal scale (“none,” “minimal,” “moderate,” “intense”). They also rated the overall degree of distress they experienced, using a scale of 1 (“not at all distressed”) to 10 (“profoundly distressed”). Scale scores of 7 or more were taken to indicate severe distress. In addition, therapists were asked to describe what was most responsible for their distress.

After they completed all written materials, two therapists at a time attended an all-day workshop with us, during which the cases of the two patients were presented and discussed in detail. In several instances, the picture of the therapist’s distress that emerged from this presentation and discussion was different from what the therapist had described on paper, in respect to the rating, the reason for the distress, or both. In such cases, the differences were specifically discussed and a final determination was made by consensus of the therapist and the other workshop participants.

The 34 patients described by the participant therapists ranged in age from 17 to 63, with an average of 37.9 years (SD=13.6). Eighteen were male, and 16 were female. Twenty-three patients, about two-thirds, were outpatients at the time of the suicide, although six of these had begun treatment with the therapist as an inpatient; in two such cases the patient had been released from the hospital shortly before the suicide. The remaining 11 patients were in hospitals or other inpatient facilities when the suicide occurred. Thirteen (38.2%) of the 34 patients had been in treatment less than 6 months before the suicide; five (14.7%) had been treated for 6–12 months, 13 (38.2%) for 13–24 months, and three (8.8%) for 25–60 months.

For most data analyses, the therapists were divided into two groups—those who experienced severe distress after the suicide and those who did not. Data related to the therapists’ specific emotions were dichotomized as intense or not intense, and Fisher’s exact test was used to assess differences between groups. Relationships between severity of distress and other categorical variables were analyzed by using Fisher’s exact test (two categories) or chi-square tests (three or more categories). Relationships between continuous outcome variables were analyzed by means of two-tailed independent group t tests.

Results

Thirteen of the 34 therapists (38.2%) experienced severe distress after their patients’ suicides. Among these 13 therapists, four factors were identified as sources of severe distress.

Failure to Hospitalize a Suicidal Patient

In three cases, the therapist’s severe distress resulted from the failure to hospitalize a patient who then died by suicide. In each of these, the patient had made the suicide intent clear in the final session; all three therapists recognized the suicide crisis, but none was able to take action and insist on hospital admission. One psychiatrist in practice for over 30 years did urge hospitalization; the patient said he would think about it, went home, and killed himself. In all three cases, the therapists’ inability to hospitalize reluctant patients had roots in the therapy itself, in which the patients had controlled what would or would not be discussed, whether and how much medication would be taken, and other matters.

A Treatment Decision

Four therapists, all with 7 to 12 years of practice, were severely distressed about a treatment decision that they felt contributed to the suicide. In one case, a ward psychiatrist allowed the socially prominent uncle of a suicidal inpatient to persuade her to let the patient out on a pass to go to dinner with him. The patient absconded, went home, and shot himself.

Another therapist acknowledged early in treating a suicidal female patient that her power to hospitalize the patient was small in comparison to the patient’s power to kill herself without the therapist knowing. That exchange formed the basis of an alliance that was sustained through more than a year of therapy. When the patient revealed she was feeling suicidal but felt reluctant to discuss it, the therapist threatened to hospitalize her. This prompted the patient to feign improvement for several weeks, while she decided on and planned her suicide. Audiotapes the patient left detailed not only her deception but also her feelings about the therapist’s threat, which she regarded as a betrayal.

In each of the other two cases, the therapist had continued to press the patient to leave an institutional setting in which he was doing reasonably well, despite signs that the patient was not ready to live on his own. One therapist gave in to pressure from the mother of his 39-year-old bipolar patient to discharge him from a group home. As discharge plans were being made, the patient told his housemates he intended to drown himself and showed them ropes and cinder blocks assembled for this purpose. The therapist was summoned and confiscated the materials. He interpreted these preparations as resistance to change and continued to encourage the patient’s move to an independent apartment. Shortly thereafter, the patient weighted himself down and drowned exactly as he had intended.

Negative Reactions by the Therapist’s Institution

In two cases, the therapist’s severe distress stemmed from his institution’s reaction to the suicide. Both cases involved therapists in training who felt blamed by hospital administrators for the patients’ suicides. One therapist, working in a municipal hospital outpatient clinic, had treated a 23-year-old woman with major depression, substance abuse, and suicidal ideation. He had been frustrated by the patient’s apparent lack of commitment to the treatment, reflected in her late arrival at her weekly sessions, unfavorable comparison of the therapist to the patient’s previous female therapist, and continued use of both alcohol and illicit drugs. At one point in the several-month therapy, while the therapist was on vacation, the patient was briefly hospitalized in a suicide crisis. About a month after discharge, she died in her apartment from a drug overdose while her roommates socialized in an adjoining room. At a postmortem conference, the hospital’s clinical director looked squarely at the therapist and said, “[The patient] appears to have died the way she was treated, with a lot of people around her but no one effectively helping her.”

Fear of a Lawsuit

In the last four cases, a potential lawsuit by relatives who blamed the therapist for the suicide was the cause of severe distress. One psychiatrist in his mid-30s lost a 56-year-old female patient to suicide. She had been referred to him by a psychopharmacologist whom the patient’s husband, a prominent local psychiatrist, had consulted. The patient had recently been hospitalized and treated with medication and ECT for severe depression. She remained deeply anguished after her release, with delusions of poverty and abandonment that appeared related to her experience as a young girl of being sent to live in an orphanage for a time when her father could not afford to support the family.

She continued to be markedly depressed and hopeless after 2 months of weekly outpatient therapy, finally revealing, at her husband’s urging, that 2 weeks earlier she had used one of his knives to “nick” herself on the neck. She minimized the incident, denying suicidal thoughts or wishes and refusing to increase her medication, but agreed to talk to her husband about attending a session with her. After discussing this during her next two sessions, she said she would ask her husband to come with her the following week. That evening, while her husband was out of the house at a meeting, she took a taxi to a spot near a river and drowned herself. The husband became enraged at the therapist and refused the therapist’s offer to meet with him and the couple’s adult children. In a note to the consultant who had referred the patient, the husband stated that he held him and the therapist responsible for his wife’s death and threatened to sue them both. Although a lawsuit did not materialize, this therapist, like the other three who were blamed by the patients’ relatives, lived for months fearing he would be made to pay for the suicide, both personally and professionally.

Expressions of Severe Distress

The severe distress of these 13 therapists was expressed in different ways. The psychiatrist with 30 years’ experience who had not hospitalized his suicidal patient had repeated dreams of failing examinations, which he said reflected feelings of inadequacy he had not had since medical school. Another therapist who had not acted to hospitalize an imminently suicidal patient had a flood in her office the day after attending her patient’s funeral. She had the fantasy that the stream of water running down the wall was the tears of the mourners, and she thought of the flood as her punishment for not preventing the suicide. A therapist named in a lawsuit brought by her patient’s wife became consumed by anger, not only toward the wife but also toward the patient for putting her in this position. She was aware that her anger sometimes became apparent in her interactions with other suicidal patients. For 2 years after his patient’s suicide, another therapist jumped up with anxiety when his telephone rang at night. He and another experienced psychiatrist for a time considered giving up their practices.

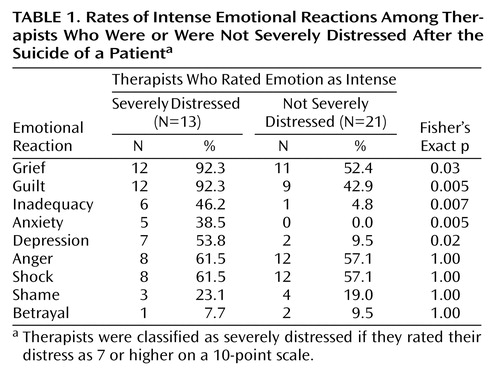

Although one emotion sometimes dominated a therapist’s response, the severely distressed therapists overall reported a significantly larger number of intense emotional reactions, with an average of 4.8 of the nine that were examined, compared to an average of 2.6 among those who did not experience severe distress (t=3.53, df=32, p=0.001). As seen in Table 1, intense levels of grief, guilt, inadequacy, anxiety, and depression were significantly more common among the severely distressed therapists than among the other therapists.

Anger was intense among 61.5% of the severely distressed therapists, including all four of those who were threatened with lawsuits. However, intense anger was also experienced by an almost equal proportion of the therapists who were not severely distressed (57.1%). As shown in Table 1, similar proportions of the two groups also experienced shock, betrayal, and shame.

Characteristics of the Therapists

Certain characteristics of the therapist, specifically gender, training status, and years in practice, appeared to affect vulnerability to severe distress. Female therapists were found to be almost twice as likely as male therapists to experience severe distress (Table 1). Severe distress was also found in over half of the therapists who were still in training at the time of the suicide, compared to one-third of other therapists. Nearly one-half of those with fewer than 15 years in practice were severely distressed, compared to just over one-tenth of those with more than 15 years. As summarized in Table 2, none of these relationships was found to be significant, probably because of the relatively small numbers in some cells. The difference in frequency of severe distress between the less and more experienced therapists approached significance.

Neither the therapist’s professional discipline nor work setting (private practice versus institutional setting) was related to severe distress to any degree. Neither did patient status at the time of the suicide (inpatient versus outpatient) nor patient’s length of time in treatment appear to contribute to severe distress among the therapists.

Discussion

About one-third of the therapists we studied experienced severe distress after the suicide of a patient. This distress was attributed to one of four factors: failure to hospitalize an imminently suicidal patient, a treatment decision the therapist felt had contributed to the patient’s suicide, the negative reaction of the therapist’s institution, or the fear of a lawsuit by relatives. None of the therapists who were not severely distressed had recognized a suicide crisis in a patient’s last session and then failed to hospitalize the patient. None perceived his or her own decisions during the treatment as having significantly contributed to the suicide. None had experienced a blaming reaction from the institution, and none had been threatened with a lawsuit by the patient’s relatives.

Although these situational factors contributed to severe distress, understanding the specific emotional responses of the therapists was crucial to understanding what underlay their distress. Two emotions—grief and guilt—were described as intense by almost all of the severely distressed therapists. In virtually all cases, the therapists’ intense grief was related to the level of their emotional connection to the patients, which appeared to make them vulnerable to feeling other emotions intensely as well. We noted that among the therapists who described the grief following the patient’s suicide as “none” or “minimal,” only one was severely distressed.

Guilt, like grief, often reflected close involvement with the patient, rather than the quality of one’s performance as a therapist. Those who reacted with intense guilt included the two therapists who felt blamed by their institutions, as well as the four who felt blamed by the patient’s relatives and were afraid of lawsuits. In all six cases, neither the therapist nor the project investigators believed the therapist’s actions had contributed to the suicide. In some instances, it was clear that relatives of the patient avoided acknowledging their own feelings of guilt by blaming and suing the therapist. It also seemed that the institutional administrators who blamed the therapists were themselves afraid of being blamed or sued by relatives. Nevertheless, being treated by fearful institutional authorities or angry relatives as if they were guilty appeared to lead therapists to feel they were.

Also among those experiencing intense guilt were three of the four therapists who believed, with some justification, that their treatment decisions had contributed to their patients’ suicides. None of the four, however, was blamed by the institution or the patient’s family or was threatened with a lawsuit.

A similar disconnection between the quality of performance, the therapist’s emotional response, and the responses of others was noted in the cases of the two therapists who considered leaving psychiatry. Neither of these therapists felt that his actions had contributed to the patient’s suicide, and the project investigators agreed. Both were experienced psychiatrists who felt they had had good rapport with their patients and were shocked by the suicides. After a difficult period, which for one therapist was complicated by a threatened lawsuit from his patient’s adult son, both eventually came to terms with the fact that even competent treatment cannot always prevent suicide—or a hostile reaction from the patient’s family. Both continued treating depressed and suicidal patients; one became a successful suicide researcher.

Gender and professional experience may affect therapists’ vulnerability to severe distress. The greater frequency of severe distress among female therapists is consistent with the observation of others that bereavement in general (16) and suicide bereavement in particular (17) is more difficult for women than men.

Consistent also with the findings of others was the greater vulnerability to severe distress among therapists still in training. This seemed to be particularly true, however, among those who were given considerable individual responsibility for their patients, such as the two trainees we have discussed who were blamed for the suicides by their institutions. Trainees who were part of an inpatient team that made collective decisions regarding patients were more apt to feel supported and less apt to be blamed or to feel intense guilt and severe distress. It is also worth noting that, while therapists who were in practice for many years were less likely than others to feel severe distress, experience alone did not protect against an intense emotional response. The highly experienced psychiatrist who failed to hospitalize a patient he knew to be imminently suicidal afterward felt intense inadequacy and self-doubt.

In addition to having had the good fortune to be spared the experience of being blamed or threatened with a lawsuit, therapists who did not respond to the suicide with severe distress sometimes appeared to have been protected by character or temperament. This was most evident in the responses that therapists gave to an open-ended item in the questionnaire that asked whether, in retrospect, there were any things they would have done differently that they thought might have prevented the suicide. All but five of the 21 therapists who were not severely distressed identified at least one change they would have made. Frequent responses included hospitalizing the patient, using more or different medications, using a different treatment technique, being more involved with the patient, involving the patient’s family in the treatment process, and communicating with prior or concurrent treatment providers. The less distressed therapists, compared to those who were severely distressed, had a greater capacity to view their misfortunes as learning opportunities rather than as occasions for self-reproach.

Limitations

The participant therapists in this project were of necessity volunteers, and thus we cannot estimate how typical they are of the greater population of therapists who lose patients to suicide. Those whose cases are reported here had a wide range of professional experience, therapeutic orientations, and personal styles. It is possible, however, that therapists not volunteering their cases may be more troubled about the treatment they provided than those willing to have their cases reviewed. The requirements and procedures of this study may also have served to select a group of more highly involved and motivated therapists. On the other hand, it is also possible that participating therapists may be more than ordinarily disturbed about the suicide of their patients. Our earlier analysis of the reactions of the first 26 of our participating therapists (6) suggested that both possibilities were represented, and our work since that time confirms this observation.

Although in our work to date we have not found the frequency of severe distress to be different among therapists trained in different disciplines, as some earlier surveys (1, 2) have suggested, our participants thus far have included far more psychiatrists than psychologists and other therapists. We will remain alert to possible differences as the study progresses.

Although we did not systematically measure the duration of severe distress, in each of the severely distressed therapists the experience was described as lasting for at least a year following the suicide. We also observed among some therapists a significant lessening of distress about 2 years after the suicide. Other therapists were still severely distressed when we saw them, however, and because we did not follow them after the workshop, we do not know how long their severe distress lasted. Duration may be a dimension of severe distress worthy of separate investigation.

Conclusions

Most clinicians are not prepared for the intense emotional responses that accompany a patient’s suicide or for the reactions of the patient’s family and the institutions in which the therapists work. The finding that over one-third of therapists who experience a patient’s suicide suffer severe distress points to the need for further study of the long-term effects of patient suicide on professional practice.

|

|

Received May 8, 2003; revision received Sept. 24, 2003; accepted Nov. 7, 2003. From the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention; the Department of Psychiatry, New York Medical College, New York; the Department of Health Services, Lehman College of the City University of New York; the Department of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, Boston; and the Department of Psychiatry, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine. Address reprint requests to Dr. Hendin, American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, 22nd Floor, 120 Wall St., New York, NY 10005; [email protected] (e-mail). Funded by grants from the Mental Illness Foundation and Janssen Pharmaceutica.

1. Chemtob CM, Hamada RS, Bauer G, Kinney B, Torigoe RY: Patients’ suicides: frequency and impact on psychiatrists. Am J Psychiatry 1988; 145:224–228Link, Google Scholar

2. Chemtob CM, Hamada RS, Bauer G, Torigoe RY, Kinney B: Patient suicide: frequency and impact on psychologists. Prof Psychol 1988; 19:416–420Crossref, Google Scholar

3. Brown HN: The impact of suicide on therapists in training. Compr Psychiatry 1987; 28:101–112Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Brown HN: Patient suicide during residency training, I: incidence, implications, and program response. J Psychiatr Ed 1987; 11:201–216Google Scholar

5. Ellis TE, Dickey TO III, Jones EC: Patient suicide in psychiatric residency programs: a national survey of training and postvention practices. Acad Psychiatry 1998; 22:181–189Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Hendin H, Lipschitz A, Maltsberger JT, Haas AP, Wynecoop S: Therapists’ reactions to patients’ suicides. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:2022–2027Link, Google Scholar

7. Alexander DA, Klein S, Gray NM, Dewar IG, Eagles JM: Suicide by patients: questionnaire study of its effect on consultant psychiatrists. BMJ 2000; 320:1571–1574Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Gitlin MJ: A psychiatrist’s reaction to a patient’s suicide (case conf). Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:1630–1634Link, Google Scholar

9. Gorkin M: On the suicide of one’s patient. Bull Menninger Clin 1985; 49:1–9Medline, Google Scholar

10. Kahne MJ: Suicide among patients in mental hospitals: a study of the psychiatrists who conducted their psychotherapy. Psychiatry 1968; 31:32–43Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Kolodny S, Binder RL, Bronstein AA, Friend RL: The working through of patients’ suicides by four therapists. Suicide Life Threat Behav 1979; 9:33–46Medline, Google Scholar

12. Litman RE: When patients commit suicide. Am J Psychother 1965; 19:570–576Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Marshall KA: When a patient commits suicide. Suicide Life Threat Behav 1980; 10:29–40Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Menninger WW: Patient suicide and its impact on the psychotherapist. Bull Menninger Clin 1991; 55:216–227Medline, Google Scholar

15. Neill K, Benensohn HS, Farber AN, Resnik HLP: The psychological autopsy: a technique for investigating a hospital suicide. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1974; 25:33–36Abstract, Google Scholar

16. Cleiren MP, Diekstra RF, Kierkof AJ, Van der Wal J: Mode of death and kinship in bereavement: focusing on “who” rather than “how.” Crisis 1994; 15:22–36Medline, Google Scholar

17. Fisher P: Bereavement in the Families of Adolescent Suicide Victims Three Years Post Death of the Adolescents: UMI Microfilm 9970192. Ann Arbor, Mich, Bell and Howell Information Learning Company, 2000Google Scholar