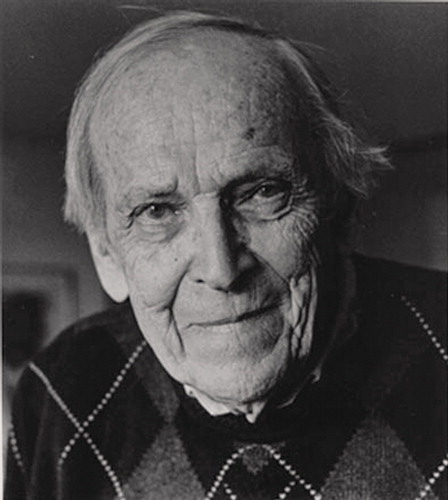

Edmund Engelman, 1907–2000

In 1938, just weeks before Sigmund Freud, his wife, and his daughter, Anna, left Vienna after the Nazi annexation of Austria, Edmund Engelman made an historic set of photographs of Freud’s office and apartment and of the Freuds. Through his work, he created a record of great historical value that brings to life the working and living quarters of Freud. The well-known photographs were published in a now out-of-print book that also contains an important introductory biographical essay by the historian Peter Gay and a brief memoir by Engelman (1). The photographs have been republished with a different introduction (2).

Engelman was an engineer who was also a highly skilled and creative photographer. Because of the Great Depression and anti-Semitism, he was unable to obtain employment in engineering, so he opened what became a well-known photo center and studio in Vienna. His diverse work included experimental cinematography, photographs used in anatomy instruction, and documentation of the 1934 destruction of a worker’s housing complex by the clerical Fascist Dollfuss regime.

At great personal risk, he accepted the request of August Aichorn, the well-known sociologist, to make a secret photographic record of Freud’s living and working environment. Engelman was acquainted with Freud’s work and his antiquities collections. Although generally regarded for their documentary value, his photographs also have artistic merit. They evoke a lost era and culture and have wonderful composition, a savvy blending of natural light sources, and a great tonal range. The portraits are stark and reveal the tension of the final days before Freud left Vienna. They are all the more remarkable considering the difficult circumstances under which they were taken, using only natural light and the relatively light-insensitive materials available at that time. The full richness of the photographs can best be appreciated in enlargements made from the original negatives, some of which are on display at the Freud museums in London and Vienna and are available as a traveling exhibit (Guild Hall of East Hampton, Inc., 158 Main St., East Hampton, N.Y. 11937). In a recent article (3), I discussed new biographical information about the artist and extensive information about the photographs.

Engelman’s own harrowing escape from Europe required bravery and imagination. He left the negatives with Aichorn for safekeeping. His fiancee joined him in France, where they were married before finally making their way to New York, where they established themselves after considerable hardship. During World War II, he worked as an aeronautical engineer, developing several innovative electronic devices. After the war, he established a photo center (Midway Camera Exchange) in Manhattan. After a long search in Europe, Engelman found his negatives in England, where they had made their way and were being held for him by Anna Freud.

He returned to engineering and had a successful career in developing photographic processing equipment. Engelman’s postwar photography was family related. His wife, Irene, became a psychiatric social worker and psychotherapist and is now retired from Hillside Hospital.

Address correspondence to Dr. Werner, Department of Psychiatry, Michigan State University, West Fee Hall, East Lansing, MI 48824-1316; [email protected] (e-mail). Photograph by Arnold Werner.

Edmund Engelman

1. Engelman E: Bergasse 19: Sigmund Freud’s Home and Offices, Vienna 1938. New York, Basic Books, 1976Google Scholar

2. Engelman E: Sigmund Freud: Bergasse 19, Vienna. New York, Universe Publishing, 1998Google Scholar

3. Werner A: Edmund Engelman: photographer of Sigmund Freud’s home and offices. Int J Psychoanal 2002; 83:445–451Crossref, Google Scholar