Obstetric Adversity and Age at First Presentation With Schizophrenia: Evidence of a Dose-Response Relationship

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The purpose of the study was to determine if a dose-response relationship exists between obstetric adversity and age at first presentation with schizophrenia. METHOD: The Dublin Psychiatric Case Register was used to identify subjects with schizophrenia. Data on obstetric complications, social class of origin, and family history of psychiatric illness were obtained for those subjects. RESULTS: A total of 409 patients with ICD-9 schizophrenia were identified. Patients with a history of obstetric complications presented earlier to psychiatric services. As the number of complications increased, the mean age at first presentation decreased. This effect was independent of social class of origin and family history of psychiatric illness. CONCLUSIONS: Obstetric adversity exerts an independent influence on the age at first presentation with schizophrenia, in a dose-response manner. This finding supports the existence of a causal relationship between obstetric adversity and age at first presentation with schizophrenia.

Obstetric adversity is associated with early age at first presentation with schizophrenia (1–5). A meta-analysis in which obstetric adversity was treated as a binary variable found that the earlier the age at onset of schizophrenia, the more likely the patient is to have a positive history of obstetric complications (6). The next step in establishing a causal relationship is to demonstrate a dose-response relationship, i.e., to demonstrate that increasing levels of exposure to the risk factor (obstetric adversity) are associated with decreasing levels of the response factor (age at presentation).

We used data from the Dublin Psychiatric Case Register and obstetric data rated at the time of birth to investigate the effect of increasing levels of obstetric adversity on age at first presentation with schizophrenia. We controlled for potential confounders such as gender, family history of psychiatric illness, and social class of origin.

Method

Detailed methods have been presented previously (5). The Dublin Psychiatric Case Register is based on data from an integrated community service serving the population (N=253,000) of west Dublin. The register is maintained by a team of psychiatric specialists who use ICD diagnostic criteria to compile a comprehensive data set on all inpatient and outpatient presentations. The data set includes information on history of psychiatric illness in relatives.

Local maternity hospital labor wards maintain detailed, structured, contemporaneously recorded data on obstetric complications. Similar data relating to home births were also transcribed. For each record of the birth of a subject who later presented with schizophrenia, we obtained data on the previous same-sex live birth as a comparison case (5), so that obstetric complications included in the records could be rated blindly (E.O’C. and M.B.) according to the scale of Lewis et al. (7). Parental social class data were determined through the Office for Registration of Births (8). We combined social classes 1 and 2 because numbers in those classes were low; the combined class was used as the reference group (lower numbers indicate higher social class).

We analyzed data using an accelerated failure time (Weibull distribution) model, which is a form of nonlinear regression that can estimate models with arbitrary, nonlinear relationships between the independent variables (risk factors) and the dependent variable (time to first presentation) (9). We used the BMDP program (release 7) for data analysis (10).

Results

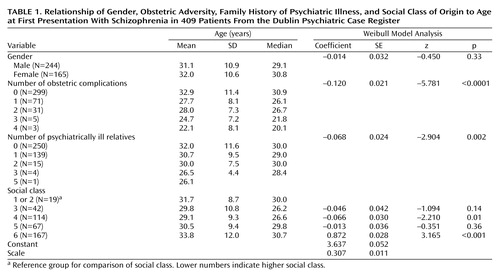

The study group comprised 409 patients (244 male patients and 165 female patients) with schizophrenia. As the number of obstetric complications increased, the mean age at first presentation decreased in a dose-response fashion (Table 1). The mean age at first presentation for patients with no obstetric complications was 32.9 years (SD=11.4), compared to 22.1 years (SD=8.1) for those with four obstetric complications. The number of obstetric complications produced the strongest model coefficient (p<0.0001) (Table 1). The model coefficient for gender was not statistically significantly different from zero, as the difference between the mean age at first presentation of male patients (31.1 years, SD=10.9) and female patients (32.0 years, SD=10.6) was less than 1 year. There was strong evidence of a reduction in the age at first presentation as the number of psychiatrically ill relatives increased (Table 1); this association was reflected in the probability for the corresponding model coefficient (p<0.002) (Table 1). The social class distribution of this group was heavily weighted toward the lower end of the social class scale (Table 1). Age at first presentation was significantly higher in social class 6 (p<0.001) and significantly lower in social class 4 (p=0.01), compared with the reference group (p<0.001) (Table 1).

Discussion

Obstetric adversity is strongly related to age at first presentation with schizophrenia in a dose-response manner and is independent of the effects of gender, family history, and social class of origin. Consistent with previous literature, we found that age at presentation decreases as number of relatives with psychiatric illness increases (11) and is highest in social class 6 (12).

The strengths of this study included selection of all subjects from a defined geographical area, inclusion of both outpatients and inpatients, blind scoring of data on obstetric complications, and use of contemporaneously recorded birth data rather than data based on maternal recall. Weaknesses included our reliance on clinical ICD diagnoses rather than DSM diagnostic interviews; analysis of age at first presentation rather than age at onset; use of the family history method rather than the family study method; inclusion of family history of any psychiatric disorder; and the low number of subjects from social classes 1 and 2, which limits the conclusions that can be drawn about social class.

Dose-response relationships form an important component of the Bradford Hill criteria for causality (13). Obstetric adversity fulfills most of the other criteria in relation to age at first presentation with schizophrenia:

| 1. | The strength, consistency and coherence of the association are supported by this and other studies (1–6). | ||||

| 2. | The temporal sequence of events is consistent with causality. | ||||

| 3. | Although few studies have examined the specificity of the association between obstetric adversity and age at first presentation with schizophrenia, three studies have found no relationship between obstetric adversity and age at first presentation with affective disorders (14, 15). | ||||

| 4. | A plausible biological rationale based on the neurodevelopmental model of schizophrenia can be used to link adverse prenatal experiences with increased risk of schizophrenia (16). The presence of a dose-response type relationship between obstetric adversity and age at presentation further supports the role of obstetric adversity in shaping the clinical features of schizophrenia. | ||||

|

Received July 2, 2003; revision received Oct. 7, 2003; accepted Oct. 9, 2003. From the Stanley Research Unit, Department of Adult Psychiatry, Hospitaller Order of St. John of God, Cluain Mhuire Service; the Department of Psychiatry, University College, Dublin; School of Mathematics, Dublin Institute of Technology, Dublin; the Health Research Board, Dublin; the Department of Psychiatric Epidemiology, University of Lund, Lund, Sweden; and Hamamatsu University School of Medicine, Hamamatsu, Japan. Address reprint requests to Dr. O’Callaghan, Stanley Research Unit, Department of Adult Psychiatry, Hospitaller Order of St. John of God, Cluain Mhuire Service, Newtownpark Avenue, Blackrock, Co. Dublin, Ireland; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by the Health Research Board of Ireland and the Stanley Medical Research Institute.

1. Eagles JM, Gibson I, Bremer MH, Clunie F, Ebmeir KP, Smith NC: Obstetric complications in DSM-III schizophrenics and their siblings. Lancet 1990; 335:1139–1141Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. O’Callaghan E, Gibson T, Colohan HA, Buckley P, Walshe DG, Larkin C, Waddington JL: Risk of schizophrenia in adults born after obstetric complications and their association with early onset of illness: a controlled study. Br Med J 1992; 305:1256–1259Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. McNeil TF, Cantor-Graae E, Nordstrom LG, Rosenlund T: Head circumference in “preschizophrenic” and control neonates. Br J Psychiatry 1993; 162:517–523Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. McCreadie RG, Connolly MA, Williamson DJ, Athawes RWB, Tilak-Singh D: The Nithsdale Schizophrenia Survey, XII: “neurodevelopmental” schizophrenia: a search for clinical correlates and putative aetiological factors. Br J Psychiatry 1994; 165:340–346Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Byrne M, Browne R, Mulryan N, Scully A, Morris M, Kinsella A, Takei N, McNeil T, Walsh D, O’Callaghan E: Labour and delivery complications and schizophrenia: case-control study using contemporaneous labour ward records. Br J Psychiatry 2000; 176:531–536Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Verdoux H, Geddes JR, Takei N, Lawrie SM, Bovet P, Eagles JM, Heun R, McCreadie RG, McNeil TF, O’Callaghan E, Stöber G, Willinger U, Wright P, Murray RM: Obstetric complications and age at onset in schizophrenia: an international collaborative meta-analysis of individual patient data. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:1220–1227{checked}Link, Google Scholar

7. Lewis SW, Owen MJ, Murray RM: Obstetric complications and schizophrenia: methodology and mechanisms, in Schizophrenia: Scientific Progress. Edited by Schulz SC, Tamminga CA. Oxford, UK, Oxford University Press, 1989, pp 56–68Google Scholar

8. O’Hare A, Whelan CT, Commins P: The development of an Irish census-based social class scale. Econ Soc Rev (Irel) 1991; 22:135–136Google Scholar

9. Kalbfleisch J, Prentice RL: The Statistical Analysis of Failure Time Data. London, John Wiley & Sons, 1980Google Scholar

10. Dixon WJ (ed): BMDP Statistical Software Manual to Accompany the 7.0 Software Release, vol 2. Berkeley, University of California Press, 1992Google Scholar

11. Basset AS, Honer WG: Evidence for anticipation in schizophrenia. Am J Hum Genet 1994; 54:864–870Medline, Google Scholar

12. Mulvany F, O’Callaghan E, Takei N, Byrne M, Fearon P, Larkin C: Effect of social class at birth on risk and presentation of schizophrenia. Br Med J 2001; 323:1398–1401Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. van Reekum R, Steiner DL, Conn DK: Applying Bradford Hill’s criteria for causation to neuropsychiatry: challenges and opportunities. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2001; 13:318–325Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Bain M, Juszczak E, McInneny K, Kendell RE: Obstetric complications and affective psychosis: two case-control studies based on structured obstetric records. Br J Psychiatry 2000; 176:523–526Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Browne R, Byrne M, Mulryan N, Scully A, Morris M, Kinsella A, McNeil TF, Walsh D, O’Callaghan E: Labour and delivery complications at birth and later mania: an Irish case register study. Br J Psychiatry 2000; 176:369–372Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. McGrath JJ, Feron FP, Burne TH, Mackay-Sims A, Eyles DW: The neurodevelopmental hypothesis of schizophrenia: a review of recent developments. Ann Med 2003; 35:86–93Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar