Family Study of Chronic Depression in a Community Sample of Young Adults

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The validity of the distinctions between dysthymic disorder, chronic major depressive disorder, and episodic major depressive disorder was examined in a family study of a large community sample of young adults. METHOD: First-degree relatives (N=2,615) of 30 probands with dysthymic disorder, 65 probands with chronic major depressive disorder, 313 probands with episodic major depressive disorder, and 392 probands with no history of mood disorder were assessed by using direct interviews and informant reports. RESULTS: The rates of major depressive disorder were significantly greater among the relatives of probands with dysthymic disorder and chronic major depressive disorder than among the relatives of probands with episodic major depressive disorder, who in turn exhibited a higher rate of major depressive disorder than the relatives of probands with no history of mood disorder. The relatives of probands with dysthymic disorder had a significantly higher rate of dysthymic disorder than the relatives of probands with no history of mood disorder, and the relatives of probands with chronic major depressive disorder had a significantly higher rate of chronic major depressive disorder than the relatives of probands with no history of mood disorder. However, the relatives of the three groups of probands with depression did not differ on rates of dysthymic disorder and chronic major depressive disorder. CONCLUSIONS: Chronic depression is distinguished from episodic depression by a more severe familial liability. This familial liability may contribute to the more pernicious course of chronic depression.

Over the past two decades there has been growing recognition that depression often assumes chronic forms (1). DSM-IV includes two categories for chronic depression: dysthymic disorder and major depressive disorder, chronic type. Although the former category was designed for mild forms of chronic depression, previous studies have reported that most persons with dysthymic disorder experience episodes of major depressive disorder at some point in their lives (1, 2). These episodes of major depressive disorder are generally superimposed on the antecedent dysthymic disorder, a phenomenon referred to as “double depression” (3), although in some cases no temporal overlap is found between the dysthymic disorder and the major depressive disorder episodes.

The DSM categories for chronic depression enhance the descriptive validity of the nomenclature by capturing some of the variation in the longitudinal course of depression. However, the clinical utility of these distinctions in terms of etiology, prognosis, and treatment response is less clear. In the analysis reported here, we used family study data to explore the distinctions between dysthymic disorder, chronic major depressive disorder, and nonchronic, or episodic, major depressive disorder.

Previous studies have found that dysthymic disorder and double depression differ from episodic major depressive disorder in important respects, although negative findings have also been reported (4, 5). Compared to patients with episodic major depressive disorder, patients with dysthymic disorder and double depression have greater axis I and II comorbidity (6–8), more extreme personality traits (9, 10), more dysfunctional cognitive biases (11), greater social impairment (12, 13), and greater childhood adversity (14). Family studies and family history studies have indicated that the relatives of patients with dysthymic disorder and double depression have significantly higher rates of total depressive disorders, dysthymic disorder, and personality disorders than the relatives of patients with episodic major depressive disorder (10, 15, 16). Finally, in a 5-year naturalistic follow-up, patients with dysthymic disorder and double depression had higher levels of depressive symptoms and higher rates of suicide attempts and psychiatric hospitalizations than patients with episodic major depressive disorder (2).

We are aware of only four studies comparing chronic major depressive disorder to episodic major depressive disorder (5, 17–19). Two of those studies found that patients with chronic major depressive disorder are more likely to attempt suicide (17, 19), and one study reported that patients with chronic major depressive disorder experienced greater chronic stress before the index episode and exhibited fewer neuroendocrine abnormalities than patients with episodic major depressive disorder (19). The findings on age at onset and number of episodes have been inconsistent, with significant differences reported in both directions (17–19). Finally, few differences have been reported on demographic variables, severity, comorbidity, childhood loss and abuse, and family history (5, 17–19).

The literature comparing the various forms of chronic depression is also limited, although the data are consistent in indicating few differences between dysthymic disorder, double depression, and chronic major depressive disorder. A series of papers from two separate studies found virtually no differences between patients with dysthymic disorder and double depression on demographics, comorbidity, personality and coping style, childhood adversity, familial psychopathology, and course (2, 8, 14, 16, 20). Moreover, other studies have reported that up to 94% of individuals with dysthymic disorder eventually develop major depressive disorder episodes (2, 21), suggesting that dysthymic disorder and double depression may be different phases of the same disorder.

Two studies have compared patients with dysthymic disorder and chronic major depressive disorder on demographic, clinical, and family history variables (5, 22). Both studies found few differences, although one (22) reported that patients with dysthymic disorder were more likely to report a family history of bipolar disorder. Finally, two large studies found virtually no differences between outpatients with double depression and those with chronic major depressive disorder on demographics, comorbidity, psychosocial functioning, early adversity, family history, and treatment response (23, 24).

This analysis uses data from the family study component of the Oregon Adolescent Depression Project (25, 26), a longitudinal investigation of a large sample of community-dwelling adolescents, to examine the distinctions between dysthymic disorder, chronic major depressive disorder, and episodic major depressive disorder. Our data extend the existing literature in three respects. First, with one exception (5), no single study has directly compared all three diagnostic groups. Second, most of the available data on the familial aggregation of chronic depression and episodic depression are based on the family history method, which relies on data from informants rather than on direct interviews with relatives. The family history method has low sensitivity (27), can be biased by the informants’ psychopathology (28), and cannot make the subtle distinctions needed to determine whether course-based subtypes of depression exhibit specificity of familial aggregation. Finally, previous studies have all used clinical samples, which are not representative of depression in the general population (29).

Method

Subjects

Selection of probands

Probands were randomly selected from high schools in western Oregon. A total of 1,709 adolescents (mean age=16.6 years, SD=1.2) completed the initial (time 1) assessments. One year later, 1,507 of the adolescents (88%) were reevaluated (time 2). Differences on demographic variables between the sample and the larger population from which it was selected were small (25), and there were few differences on demographic and clinical variables between the time-2 participants and those who declined to participate at time 2.

When they were 24 years old, all probands with a history of major depressive disorder (N=360) or other psychopathology (N=284) by time 2 and a random sample of participants with no history of psychopathology by time 2 (N=457) were invited to participate in a third (time 3) evaluation. Of the 1,101 time-2 participants selected for a time-3 interview, 941 (85%) completed the evaluation at age 24 years. The time-2 diagnostic groups did not differ in their participation rates at time 3.

Selection of relatives

We assessed lifetime psychopathology in the first-degree relatives (≥14 years) of the probands in the time-3 evaluation. Informant data were also collected from probands and/or another relative. Of the 941 probands with time-3 data, family diagnostic data were available for 803 (85%). Of the 2,750 first-degree relatives for whom diagnostic information was collected, 1,744 relatives (63%) participated in direct interviews.

Sample for this report

All probands with data on at least one first-degree relative were included, except for those with a history of a nonaffective psychotic disorder or bipolar disorder. The probands included 30 with a lifetime history of dysthymic disorder, 65 with a history of chronic major depressive disorder, 313 with a history of episodic major depressive disorder, and 392 with no lifetime history of mood disorder.

The probands’ diagnoses were based on DSM-III-R criteria; the relatives’ diagnoses were based on DSM-IV criteria. The DSM-III-R and DSM-IV criteria for dysthymic disorder include a duration requirement of 2 years for adults and 1 year for children and adolescents. To be consistent with this criterion and to maximize the sample size, we shortened the required duration for chronic major depressive disorder to 1 year in the probands. However, the pattern of results was similar when a 2-year duration requirement was used.

Diagnoses were assigned hierarchically on the basis of lifetime history through age 24 years. Probands with a history of dysthymic disorder were included in the dysthymic disorder group regardless of the presence or length of major depressive disorder episodes. Probands were assigned to the chronic major depressive disorder group if they had a history of major depressive disorder, no history of dysthymic disorder, and at least one major depressive disorder episode lasting at least 12 months. Probands were assigned to the episodic major depressive disorder group if they had a history of major depressive disorder, no history of dysthymic disorder, and no major depressive disorder episode lasting 12 months or longer. After complete description of the study to the subjects, written informed consent was obtained.

Consistent with the literature (2, 21), 28 of the 30 probands with dysthymic disorder had developed an episode of major depressive disorder by age 24 years. Five probands with dysthymic disorder had a major depressive disorder episode that lasted 12 months or longer. However, excluding these five probands from the analyses did not change the results.

Diagnostic Interviews

Proband interviews

At time 1, probands were interviewed with a modified version of the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children (K-SADS) (30). At time 2 and time 3, probands were interviewed with the Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation (31) to elicit information about the onset and course of psychopathology since the previous evaluation.

To assess interrater reliability, independent raters reviewed audiotapes of a random sample of interviews (range=166–233 interviews). Kappas for the reliability of a lifetime diagnosis of major depressive disorder at time 1, time 2, and time 3 ranged from 0.75 to 0.86. The number of cases of dysthymic disorder and chronic major depressive disorder was sufficient to calculate interrater reliability only at time 1, for which the kappas were 0.58 and 0.95 for the respective diagnoses.

Interviews with relatives

Parents and siblings age 18 years or older were interviewed with the nonpatient edition of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (32). Siblings between age 14 and 18 years were interviewed with the K-SADS. The interviewers were unaware of probands’ diagnoses. Kappas for the interrater reliability of lifetime diagnoses of major depressive disorder, dysthymic disorder, and chronic major depressive disorder were 0.94, 0.88, and 0.57, respectively (N=184).

Family history data were collected by using a modified version of the Family Informant Schedule and Criteria (33). Kappas for the interrater reliability of lifetime diagnoses of major depressive disorder and dysthymic disorder were 0.90 and 1.00, respectively (N=242). Data on the reliability of chronic major depressive disorder were not available.

Proband interviews at time 3 and interviews with relatives and informants were conducted by telephone. Interviews by telephone have generally been found to yield results that are comparable to those of face-to-face interviews (34). Most interviewers had advanced degrees in clinical or counseling psychology or social work and had several years of clinical experience.

Two senior diagnosticians who were unaware of the probands’ diagnoses provided lifetime best-estimate DSM-IV diagnoses for the relatives. Kappas for the interrater reliability of major depressive disorder and dysthymic disorder diagnoses, based on independently derived best-estimate diagnoses before the consensus resolution of discrepancies, were 0.91 and 0.89, respectively. Data on the reliability of chronic major depressive disorder diagnoses were not available.

Data Analysis

Probands with no history of psychopathology were undersampled in the time-3 follow-up, hence data for probands and relatives were weighted according to the probability of the proband’s selection at time 3. Descriptive features were compared between groups by using chi-square tests for categorical variables and one-way analysis of variance for continuous variables. Rates of lifetime psychiatric disorders in the relatives were analyzed by using Cox proportional hazards models, adjusted for the sex and generation (parent/sibling) of the relative and whether the relative was directly interviewed. In analyses examining the rates of nonmood disorders in the relatives, the corresponding rate of the nonmood disorder in the probands was included as a covariate. Because the data for the relatives were clustered within families and could not be considered as independent observations, the use of standard statistical tests would underestimate the standard errors, increasing the chance of type I errors. Therefore, comparisons were conducted by using Taylor series linearization, which takes the clustered structure of the data into account (35). Due to the small cell sizes for rates of bipolar disorder in the relatives, the groups were compared on this variable by using Fisher’s exact test.

Results

Descriptive Characteristics of Probands and Relatives

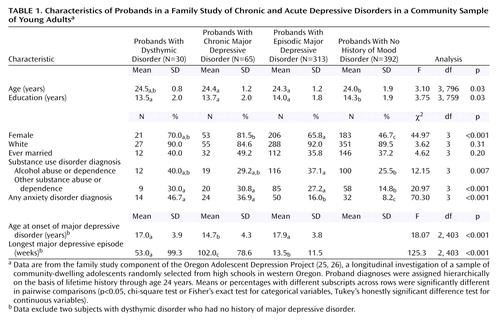

There were small, but significant, differences between the proband groups on age, sex, and education (Table 1). The probands with chronic major depressive disorder and episodic major depressive disorder were older than those with no history of mood disorder. The groups of depressed probands had higher proportions of female subjects than the group with no history of mood disorder, and the probands with chronic major depressive disorder had a higher proportion of female subjects than the probands with episodic major depressive disorder. Finally, the probands with no history of mood disorder had more education than those in the depression groups.

It is not surprising that the proband groups differed on a number of clinical variables. The groups of depressed probands had higher rates of lifetime anxiety disorders and substance abuse/dependence than the probands with no history of mood disorder. In addition, the probands with dysthymic disorder and chronic major depressive disorder had higher rates of anxiety disorders than the probands with episodic major depressive disorder. The probands with episodic major depressive disorder had a higher rate of lifetime alcohol abuse/dependence than the probands with no history of mood disorder. The probands with chronic major depressive disorder had an earlier onset of major depressive disorder than the probands with episodic major depressive disorder and the probands with dysthymic disorder. The mean age at onset of dysthymic disorder for the probands with dysthymic disorder was 13.9 years (SD=4.2). If both dysthymic disorder and major depressive disorder are considered together, the mean age at onset of any depressive disorder was significantly earlier in the probands with dysthymic disorder than in the probands with chronic major depressive disorder, who in turn had an earlier age at onset of any depressive disorder than the probands with episodic major depressive disorder (F=35.85, df=2, 405, p<0.001). Finally, the duration of the longest lifetime episode of major depressive disorder was greater in the probands with chronic major depressive disorder than in the probands with dysthymic disorder who also had a history of major depressive disorder, who in turn had longer episodes than the probands with episodic major depressive disorder.

The groups did not differ in the age of the relatives (mean=40.2 years, SD=13.5) or their relation to the probands (30.5% of the relatives were mothers, 29.8% were fathers, 19.5% were sisters, and 20.2% were brothers). Of the relatives, 63.5% received direct interviews. There was a significant difference between the groups in the proportion of relatives with direct interviews (χ2=11.20, df=3, p=0.01). Pairwise comparisons indicated that a greater number of the relatives of probands with no history of mood disorder (66.6%) than of probands with episodic major depressive disorder (60.3%) were personally interviewed.

Rates of Mood Disorders in Relatives

Rates of mood and nonmood disorders in the relatives of probands are shown in Table 2. The relatives of probands with chronic major depressive disorder had a significantly higher rate of bipolar disorder than the relatives of probands with episodic major depressive disorder (p=0.02, Fisher’s exact test) and no history of mood disorder (p<0.02, Fisher’s exact test).

The rate of major depressive disorder was greater in the relatives of probands with dysthymic disorder than the relatives of probands with episodic major depressive disorder (hazard ratio=1.45, 95% confidence interval [CI]=1.00–2.10, p=0.05) and no history of mood disorder (hazard ratio=2.13, 95% CI=1.47–3.11, p<0.001). Similarly, the relatives of probands with chronic major depressive disorder had a higher rate of major depressive disorder than the relatives of probands with episodic major depressive disorder (hazard ratio=1.41, 95% CI=1.07–1.87, p<0.02) and no history of mood disorder (hazard ratio=2.08, 95% CI=1.56–2.76, p<0.001). In addition, the relatives of probands with episodic major depressive disorder exhibited a higher rate of major depressive disorder than the relatives of probands with no history of mood disorder (hazard ratio=1.47, 95% CI=1.21–1.79, p<0.001).

We also examined rates of recurrent major depressive disorder, a narrower and more familial subtype of major depressive disorder that is defined by a history of multiple episodes, regardless of chronicity (37). The results were similar. The relatives of probands with dysthymic disorder exhibited a higher rate of recurrent major depressive disorder than the relatives of probands with episodic major depressive disorder (hazard ratio=1.93, 95% CI=1.24–3.01, p<0.004) and no history of mood disorder (hazard ratio=3.12, 95% CI=2.00–4.88, p<0.001); the relatives of probands with chronic major depressive disorder exhibited higher rates of recurrent major depressive disorder than the relatives of probands with episodic major depressive disorder (hazard ratio=1.52, 95% CI=1.06–2.18, p=0.02) and no history of mood disorder (hazard ratio=2.45, 95% CI=1.69–3.55, p<0.001); and the relatives of probands with episodic major depressive disorder had a higher rate of recurrent major depressive disorder than the relatives of probands with no history of mood disorder (hazard ratio=1.61, 95% CI=1.24–2.10, p<0.001).

The rate of dysthymic disorder was greater in the relatives of probands with dysthymic disorder than in the relatives of probands with no history of mood disorder (hazard ratio=3.11, 95% CI=1.43–6.77, p=0.004). In addition, the relatives of probands with episodic major depressive disorder had a higher rate of dysthymic disorder than the relatives of probands with no history of mood disorder (hazard ratio=2.15, 95% CI=1.38–3.36, p<0.001).

The rate of chronic major depressive disorder was greater in the relatives of probands with chronic major depressive disorder than in the relatives of probands with no history of mood disorder (hazard ratio=2.30, 95% CI=1.26–4.20, p<0.01). None of the other comparisons of rates of chronic major depressive disorder in the relatives was significant.

We also examined the rates of episodic major depressive disorder in the relatives. Higher rates of episodic major depressive disorder were found among the relatives of probands with dysthymic disorder (hazard ratio=2.06, 95% CI=1.38–6.06, p<0.001), chronic major depressive disorder (hazard ratio=1.91, 95% CI=1.38–2.65, p<0.001), and episodic major depressive disorder (hazard ratio=1.46, 95% CI=1.17–1.81, p<0.001), compared with the relatives of probands with no history of mood disorder. The three groups of depressed probands did not differ in the rates of episodic major depressive disorder in the relatives.

The earlier onset of depression in the probands with dysthymic disorder and those with chronic major depressive disorder, compared to the probands with episodic major depressive disorder, might conceivably account for the differences in rates of major depressive disorder and recurrent major depressive disorder in their relatives (36). Hence, we conducted an additional set of survival analyses using age at onset of the proband’s earliest depressive disorder (dichotomized as before age 12 years versus age 12 years or older) as a covariate. These analyses were limited to relatives of the three groups of depressed probands. The percentages of probands with dysthymic disorder, chronic major depressive disorder, and episodic major depressive disorder who had onset of depression before age 12 years were 42.9%, 21.5%, and 6.4%, respectively. The relatives of probands with chronic major depressive disorder continued to have significantly higher rates of major depressive disorder (hazard ratio=1.39, 95% CI=1.05–1.84, p=0.02) and recurrent major depressive disorder (hazard ratio=1.49, 95% CI=1.03–2.16, p=0.03), compared with the relatives of probands with episodic major depressive disorder. The relatives of probands with dysthymic disorder had a significantly higher rate of recurrent major depressive disorder (hazard ratio=1.88, 95% CI=1.16–3.03, p=0.01) and a higher rate of major depressive disorder that approached significance (hazard ratio=1.41, 95% CI=0.96–2.08, p=0.08), compared with the relatives of probands with episodic major depressive disorder. The proband’s age at onset of depression was not associated with rates of major depressive disorder (hazard ratio=0.90, 95% CI=0.63–1.28, p=0.56) and recurrent major depressive disorder (hazard ratio=0.90, 95% CI=0.58–1.39, p=0.64) in their relatives, although the range of onset ages was restricted, given the relative youth of the sample.

Rates of Nonmood Disorders in Relatives

The relatives of probands with chronic major depressive disorder had a higher rate of anxiety disorders than the relatives of probands with no history of mood disorder (hazard ratio=1.76, 95% CI=1.06–2.92, p=0.03). In addition, there were higher rates of alcohol abuse/dependence among the relatives of probands with dysthymic disorder (hazard ratio=1.73, 95% CI=1.22–2.47, p=0.002), chronic major depressive disorder (hazard ratio=1.51, 95% CI=1.11–2.04, p=0.008), and episodic major depressive disorder (hazard ratio=1.39, 95% CI=1.16–1.66, p<0.001), compared with the relatives of probands with no history of mood disorder. The groups did not differ on rates of other substance abuse/dependence in relatives.

Discussion

We examined the distinctions between dysthymic disorder, chronic major depressive disorder, and episodic major depressive disorder using family study data from a large community sample of young adults. The relatives of probands in all three depressed groups exhibited significantly higher rates of major depressive disorder than the relatives of probands with no history of mood disorder, consistent with the well-established finding that depression aggregates in families (37). However, the relatives of probands with each of the two chronic forms of depression (dysthymic disorder and chronic major depressive disorder) had significantly higher rates of major depressive disorder than the relatives of probands with episodic major depressive disorder. Indeed, the risk of major depressive disorder was more than 40% greater in the relatives of probands with dysthymic disorder and chronic major depressive disorder, compared to relatives of probands with episodic major depressive disorder, and the differences were even greater when the analyses were restricted to recurrent major depressive disorder in relatives. This finding is consistent with, although stronger than, the findings in several previous studies (10, 16). These results indicate that chronic forms of depression are more severe than episodic depression not only because they have a more pernicious course but also because they have a greater familial liability. Moreover, the results suggest that a greater familial vulnerability may increase the risk of chronicity in depression.

There was some limited evidence for the specificity of familial aggregation of these forms of depression. The highest rate of dysthymic disorder was found among the relatives of probands with dysthymic disorder, whose rate of dysthymic disorder differed significantly from that of the relatives of probands with no history of mood disorder. However, none of the comparisons between the three depressed groups were statistically significant. In addition, the higher rate of dysthymic disorder in the relatives of probands with episodic major depressive disorder compared to the relatives of probands with no history of mood disorder suggests only partial specificity of transmission of dysthymic disorder.

The one previous study examining this issue found a significantly higher rate of dysthymic disorder in the relatives of probands with dysthymic disorder than in the relatives of probands with episodic major depressive disorder, while the rate of dysthymic disorder in relatives of probands with episodic major depressive disorder did not differ from that in the relatives of nonpsychiatric comparison subjects (16). One potential explanation for these differences involves statistical power. In both studies, the relatives of probands with dysthymic disorder had the highest rate of dysthymic disorder, followed by the relatives of probands with episodic major depressive disorder, and then by the relatives of comparison probands. However, the dysthymic disorder group was appreciably larger and the episodic major depressive disorder group was considerably smaller in the earlier study, compared to the present study. Hence, the earlier study had greater power to detect differences between the dysthymic disorder group and episodic major depressive disorder group, while the present study had greater power to detect differences between the episodic major depressive disorder group and the comparison group with no history of mood disorder. An alternative explanation involves the heterogeneity of the episodic major depressive disorder group in the current study. We used data from a young, community-dwelling sample that may have included a subgroup with nonfamilial major depressive disorder whose episode of depression represented a relatively mild, transient reaction to stress. If so, the presence of this subgroup could explain why there was a higher rate of major depressive disorder in the relatives of probands with dysthymic disorder and probands with chronic major depressive disorder than in the relatives of probands with episodic major depressive disorder. At the same time, as the probands with episodic major depressive disorder were relatively young, it is possible that another subgroup will eventually develop chronic depressive conditions, which would account for the higher rate of dysthymic disorder in the relatives of probands with episodic major depressive disorder than in the relatives of probands with no history of mood disorder.

Limited support for specificity was also provided by the results showing that the relatives of probands with chronic major depressive disorder were the only group with a higher rate of chronic major depressive disorder than the relatives of probands with no history of mood disorder. Again, however, there were no significant differences among the relatives of the three groups of depressed probands. Finally, there was no evidence of the specificity of familial aggregation of episodic major depressive disorder.

We found that the relatives of both groups of probands with chronic depression differed from the relatives of probands with episodic major depressive disorder in their rates of major depressive disorder and recurrent major depressive disorder. In contrast, the relatives of probands with dysthymic disorder and of those with chronic major depressive disorder did not differ significantly in the rate of any form of mood or nonmood disorder. Although the power of these comparisons was limited because of the small samples, this finding is consistent with previous studies that have used the family history method (5, 23, 24).

Taken together, these findings indicate that the differences between chronic and episodic forms of depression are greater than the differences among the chronic forms of depression (23). Thus, the possibility of simplifying the classification of mood disorders by combining the various forms of chronic depression and introducing a distinction between chronic and episodic depression is worth considering (5). As distinctions in severity are also clinically important, these groups could be subdivided by severity, producing a fourfold classification consisting of moderate-to-severe chronic (double depression and chronic major depressive disorder), mild chronic (dysthymic disorder), moderate-to-severe acute (episodic major depressive disorder), and mild acute (minor depression) depressive conditions (24).

Three other findings are worthy of comment. First, the relatives of probands with chronic major depressive disorder had a higher rate of bipolar disorder than the relatives of probands with episodic major depressive disorder and the relatives of probands with no history of mood disorder. However, this finding conflicts with a previous report that patients with dysthymic disorder were more likely to have a family history of bipolar disorder than patients with chronic major depressive disorder (22).

Second, even after we controlled for the presence of anxiety disorders in the probands, the rate of anxiety disorders was significantly greater in the relatives of probands with chronic major depressive disorder than in the relatives of probands with no history of mood disorder. This difference suggests that there may be a shared liability between chronic, but not episodic, major depressive disorder and at least some anxiety disorders.

Finally, the rate of alcohol abuse/dependence was high in the relatives of all three groups of depressed probands. As our analysis controlled for the presence of alcohol abuse/dependence in the probands, these data suggest that there may be a shared liability between the familial risks for alcoholism and both chronic and episodic forms of depression.

This study had significant strengths, including the use of a large community sample, direct interviews with relatives, multiple assessments of the probands from adolescence to early adulthood, and the inclusion of probands with dysthymic disorder, chronic major depressive disorder, episodic major depressive disorder, and no history of mood disorder in the same study. However, the study also had a number of limitations. First, the number of probands in the two chronic depression groups was small, limiting the power of the statistical comparisons. Second, a depressive episode lasting 12, rather than 24, months was required for a diagnosis of chronic major depressive disorder. Third, the differential diagnosis of dysthymic disorder, chronic major depressive disorder, and episodic major depressive disorder was based on participants’ retrospective reports of the course of depression over long periods of time. The retrospective reporting may have produced some misclassifications, attenuating differences between groups. Fourth, almost all probands with dysthymic disorder experienced episodes of major depressive disorder, hence the results may differ for a sample with “pure” dysthymic disorder. Fifth, five probands in the dysthymic disorder group had major depressive disorder episodes lasting more than 12 months, creating some overlap between the dysthymic disorder and chronic major depressive disorder groups. However, the results were the same when these five probands were excluded. Sixth, the probands were young, hence some of the subjects with no history of mood disorder may develop mood disorders in the future, and some subjects with episodic major depressive disorder may develop dysthymic disorder or chronic major depressive disorder. Finally, we conducted a number of statistical comparisons, hence some differences may be due to chance.

In conclusion, we found that probands with chronic forms of depression (dysthymic disorder and chronic major depressive disorder) exhibit a significantly higher level of familial aggregation of major depressive disorder than probands with episodic major depressive disorder. This finding suggests that chronic depressions are distinguished from episodic depressions by a greater familial liability that may contribute to their more pernicious course. There was also limited evidence that the two forms of chronic depression may exhibit some degree of specificity of familial aggregation; however, this specificity was more evident in comparisons with the comparison subjects with no history of mood disorder than in comparisons among the depressed groups.

|

|

Received April 8, 2003; revision received Aug. 20, 2003; accepted Aug. 22, 2003. From the Departments of Psychology and Psychiatry, Stony Brook University; and the Oregon Research Institute, Eugene, Ore. Address reprint requests to Dr. Klein, Department of Psychology, Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, NY 11794–2500; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by NIMH grants MH-40501, MH-50522, and MH-52858 (Dr. Lewinsohn) and MH-66023 (Dr. Klein).

1. Keller MB, Klein DN, Hirschfeld RMA, Kocsis JH, McCullough JP, Miller I, First MB, Holzer CP III, Keitner GI, Marin DB, Shea T: Results of the DSM-IV mood disorders field trial. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:843–849Link, Google Scholar

2. Klein DN, Schwartz JE, Rose S, Leader JB: Five-year course and outcome of dysthymic disorder: a prospective, naturalistic follow-up study. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:931–939Link, Google Scholar

3. Keller MB, Shapiro RW: “Double depression”: superimposition of acute depressive episodes on chronic depressive disorders. Am J Psychiatry 1982; 139:438–442Link, Google Scholar

4. Miller IW, Norman WH, Dow MG: Psychosocial characteristics of “double depression.” Am J Psychiatry 1986; 143:1042–1044Link, Google Scholar

5. Yang T, Dunner DL: Differential subtyping of depression. Depress Anxiety 2001; 13:11–17Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Garyfallos G, Adamopoulou A, Karastergiou A, Voikli M, Sotiropoulou A, Donias S, Giouzepas J, Paraschos A: Personality disorders in dysthymia and major depression. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1999; 99:332–340Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Markowitz JC, Moran ME, Kocsis JH, Frances AJ: Prevalence and comorbidity of dysthymic disorder among psychiatric outpatients. J Affect Disord 1992; 24:63–71Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Pepper CM, Klein DN, Anderson RL, Riso LP, Ouimette PC, Lizardi H: DSM-III-R axis II comorbidity in dysthymia and major depression. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:239–247Link, Google Scholar

9. Harkness KL, Bagby RM, Joffe RT, Levit A: Major depression, chronic minor depression, and the five-factor model of personality. Eur J Personality 2002; 16:271–281Crossref, Google Scholar

10. Klein DN, Taylor EB, Dickstein S, Harding K: Primary early-onset dysthymia: comparison with primary non-bipolar, non-chronic major depression on demographic, clinical, familial, personality, and socioenvironmental characteristics and short-term outcome. J Abnorm Psychol 1988; 97:387–398Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Riso LP, du Toit PL, Blandino JA, Penna S, Darcy S, Duin JS, Pacoe EM, Grant MM, Ulmer CS: Cognitive aspects of chronic depression. J Abnorm Psychol 2003; 112:72–80Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Hays RD, Wells KB, Sherbourne CD, Rogers W, Spritzer K: Functioning and well-being outcomes of patients with depression compared with chronic general medical illnesses. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995; 52:11–19Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Linzer M, Hahn SR, Williams JBW, deGruy FV III, Brody D, Davies M: Health-related quality of life in primary care patients with mental disorders: results from the PRIME-MD 1000 study. JAMA 1995; 274:1511–1517Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Lizardi H, Klein DN, Ouimette PC, Riso LP, Anderson RL, Donaldson SK: Reports of the childhood home environment in early-onset dysthymia and episodic major depression. J Abnorm Psychol 1995; 104:132–139Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Goodman DW, Goldstein RB, Adams PB, Horwath E, Sobin S, Wickramaratne P, Weissman MM: Relationship between dysthymia and major depression: an analysis of family study data. Depression 1994/1995; 2:252–258Google Scholar

16. Klein DN, Riso LP, Donaldson SK, Schwartz JE, Anderson RL, Ouimette PC, Lizardi H, Aronson TA: Family study of early-onset dysthymia: mood and personality disorders in relatives of outpatients with dysthymia and episodic major depression and normal controls. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995; 52:487–496Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Garvey MJ, Tollefson GD, Tuason VB: Is chronic primary major depression a distinct depression subtype? Compr Psychiatry 1986; 27:446–448Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Rush AJ, Laux L, Giles DE, Jarrett RB, Weissenburger J, Feldman-Koffler F, Stone L: Clinical characteristics of outpatients with chronic major depression. J Affect Disord 1995; 34:25–32Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Sźadóczky E, Fazekas I, Rihmer Z, Arató M: The role of psychosocial and biological variables in separating chronic and non-chronic major depression and early-late-onset dysthymia. J Affect Disord 1994; 32:1–11Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. McCullough JP, Braith JA, Chapman RC, Kasnetz MD, Carr KF, Cones JH, Fielo J, Roberts WC: Comparison of dysthymic major and nonmajor depressives. J Nerv Ment Dis 1990; 178:596–597Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Kovacs M, Akiskal HS, Gatsonis C, Parrone PL: Childhood-onset dysthymic disorder: clinical features and prospective naturalistic outcome. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:365–374Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Cassano GB, Savino M: Chronic major depressive episode and dysthymia: comparison of demographic and clinical characteristics. Eur Psychiatry 1993; 8:277–279Google Scholar

23. McCullough JP, Klein DN, Keller MB, Holzer CE, Davis SM, Kornstein SG, Howland RH, Thase ME, Harrison WM: Comparison of DSM-III-R chronic major depression and major depression superimposed on dysthymia (double depression): validity of the distinction. J Abnorm Psychol 2000; 109:419–427Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. McCullough JP, Klein DN, Borian FE, Munsaka MS, Howland RH, Riso LP, Keller MB: Chronic forms of DSM-IV major depression: validity of the distinctions. J Abnorm Psychol (in press)Google Scholar

25. Lewinsohn PM, Hops H, Roberts RE, Seeley JR, Andrews JA: Adolescent psychopathology, I: prevalence and incidence of depression and other DSM-III-R disorders in high school students. J Abnorm Psychol 1993; 102:133–144Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Klein DN, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR, Rohde P: A family study of major depressive disorder in a community sample of adolescents. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001; 58:13–20Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Cohen PR: The effects of instruments and informants on ascertainment, in Relatives at Risk for Mental Disorders. Edited by Dunner DL, Gershon ES, Barrett JE. New York, Raven Press, 1988, pp 32–51Google Scholar

28. Kendler KS, Silberg JL, Neale MC, Kessler RC, Heath AC, Eaves LJ: The family history method: whose psychiatric history is measured? Am J Psychiatry 1991; 148:1501–1504Link, Google Scholar

29. Costello CG: The similarities and dissimilarities between community and clinical cases of depression. Br J Psychiatry 1990; 157:812–821Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Orvaschel H, Puig-Antich J, Chambers WJ, Tabrizi MA, Johnson R: Retrospective assessment of prepubertal major depression with the Kiddie-SADS-E. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry 1982; 21:392–397Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Keller MB, Lavori PW, Friedman B, Nielsen E, Endicott J, McDonald-Scott P, Andreasen NC: The Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation: a comprehensive method for assessing outcome in prospective longitudinal studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1987; 44:540–548Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JB: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders—Non-Patient Edition (SCID-I/NP), version 2.0. New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1996Google Scholar

33. Mannuzza S, Fyer AJ: Family Informant Schedule and Criteria (FISC), July 1990 revision. New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Anxiety Disorders Clinic, 1990Google Scholar

34. Rohde P, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR: Comparability of telephone and face-to-face interviews in assessing axis I and II disorders. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:1593–1598Link, Google Scholar

35. King TM, Beaty TH, Liang KY: Comparison of methods for survival analysis of dependent data. Genet Epidemiol 1996; 13:138–158Crossref, Google Scholar

36. Weissman MM, Wickramaratne P, Merikangas KR, Leckman JF, Prusoff BA, Caruso KA, Kidd KK, Gammon GD: Onset of major depression in early adulthood: increased familial loading and specificity. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1984; 41:1136–1143Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Sullivan PF, Neale MC, Kendler KS: Genetic epidemiology of major depression: review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:1552–1562Link, Google Scholar