Risk Factors for Suicide in Blacks and Whites: An Analysis of Data From the 1993 National Mortality Followback Survey

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Data on risk factors for suicide in blacks in the United States are needed, given the dramatic increase in the black suicide rate from 1980 to 1997. The 1993 National Mortality Followback Survey represented an unprecedented opportunity to identify risk factors for suicide in blacks and to determine whether race differences (black versus white) in risk factors exist. METHOD: Multiple logistic regression analyses were used to compare cases of suicide (150 suicides in blacks and 1,279 suicides in whites) with cases of accidental deaths (737 cases in blacks and 3,458 cases in whites). Predictors of interest were 18 items tapping four domains: antisocial behavior, substance use/abuse, depressive symptoms, and psychotic symptoms. RESULTS: Four items distinguished suicides from accidental deaths in both black and whites: death ideation, suicidal ideation, bizarre behavior, and making violent threats. Items in two of the four domains discriminated risk for suicide in whites more strongly than in blacks: reports of community complaints and problem drinking. No variable conferred greater risk for suicide in blacks than in whites. CONCLUSIONS: The current study underscores the need for examination of race differences in risk factors for suicide. It is also essential to examine variables that were unavailable in the National Mortality Followback Survey data set, particularly racism, perceived discrimination, and feelings of alienation from the dominant culture.

Suicide is the fifth leading cause of years of potential life lost before age 75 (1) and the 11th leading cause of death (2) in the United States. Historically, whites have had higher suicide rates than blacks, but between 1980 and 1995 the overall rate in blacks increased, driven by a dramatic increase among male adolescents and young adult men (3). Yet suicide among blacks remains poorly understood. Eight published case-control studies of suicide in the United States conducted since 1985 (4–11) have yielded data for only 97 blacks, and only a handful of prospective studies examining suicidal behavior and its correlates have reported data stratified by race (12–14). It is difficult, therefore, to draw meaningful conclusions about factors relevant to suicide in blacks, and the formulation and implementation of suicide prevention programs targeting at-risk blacks have been compromised.

Postmortem, case-control studies of predominantly white samples have established that antisocial behavior (7, 9, 15), substance use/abuse (15–17), mood disorders (15–18), and nonaffective psychotic disorders (15, 16, 18) confer risk for suicide. Only Kung and associates (19) attempted to identify race differences in risk factors. Using the 1986 National Mortality Followback Survey data set, Kung and colleagues reported that use of mental health services conferred risk for suicide in both blacks and whites. Whites who had at least a high school education, lived alone, and held blue-collar jobs were at greater risk; these demographic variables did not distinguish suicides in blacks. Heavy drinking was associated with suicide in whites, but not in blacks. Only 25 suicides in blacks were included in the 1986 National Mortality Followback Survey, so the nil findings for demographics and drinking could be ascribed to the small sample size.

The 1993 National Mortality Followback Survey oversampled black decedents and yielded a sample of 150 suicides in blacks. We used that data set to determine if antisocial behavior, substance use/abuse, depressive symptoms, and psychotic symptoms amplified risk among blacks. We also investigated whether there were race differences in risk factors for suicide.

Method

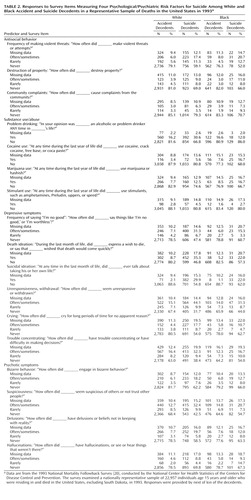

The 1993 National Mortality Followback Survey (20) was conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The National Mortality Followback Survey is a multicomponent survey that examined a nationally representative sample of individuals age 15 years and older who were residing in and died in the United States in 1993, excluding South Dakota. A sample of 22,957 death certificates was drawn for the 1993 Current Mortality Sample. This subgroup is a 10% systematic sampling of death certificates received at the National Center for Health Statistics from state vital statistics offices. Death certificates do not provide data on situational (e.g., place of death) parameters surrounding the death. The 1993 National Mortality Followback Survey oversampled deaths due to homicide, suicide, and unintentional injury. Next of kin, identified on the death certificate, were contacted and asked to participate in the survey. Respondents were asked to provide information by telephone on the decedent’s background characteristics, lifestyle, health, and type of care received in the last year of life. Interviewers provided no clarification or operational definitions. The directions were as follows: “Now I’m going to read a list of behaviors. Please tell me how frequently (name of decedent) engaged in these behaviors during the last year of life. We would like to know if (name of decedent) engaged in the behavior often, sometimes, rarely, or never.”

For our analysis, suicide decedents (N=1,488; 157 blacks and 1,331 whites) were compared with fatal accident decedents (N=4,395; 783 blacks and 3,612 whites). The latter included decedents of motor vehicle accidents (drivers, passengers, motorcycle operators, pedestrians), poisoning, falls, and other accidents (e.g., drowning, choking). The dependent variable was cause of death, suicide or accident. The use of an accident victim comparison group allows for control of sudden death and the subsequent bereavement (21), acknowledging that there may be differences in grief response after different causes of death. Misclassification of suicides by drivers as accidents is infrequent and has a negligible influence on suicide statistics (22, 23).

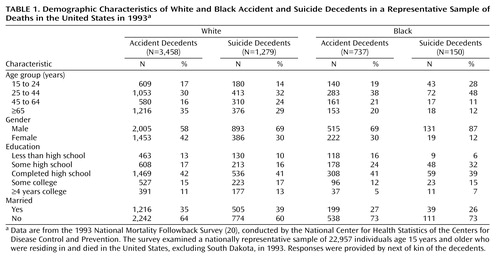

We restricted the sample to white and black non-Hispanics. There were 4,943 white and 940 black accident and suicide decedents. Records for 206 (4.2%) whites and 53 (5.6%) blacks were excluded from the analysis because of missing data for one or more of the following covariates: education, marital status, age, or gender. As for gender, among suicides decedents in the National Mortality Followback Survey, the male-female ratio was 6.9:1 for blacks and 2.3:1 for whites. Demographic information is presented in Table 1. Predictors were grouped into four domains: antisocial behavior, substance use/abuse, depressive symptoms, and psychotic symptoms. The items composing these domains are presented in Table 2.

All statistical analyses were conducted with SUDAAN software (24). SUDAAN uses Taylor series approximation methods to compute variances that allow adjustment for the multistage cluster sampling strategy. Weights were used to adjust for survey oversampling and nonresponse to yield population estimates of suicide. The SUDAAN LOGISTIC procedure uses generalized estimating equation techniques to fit generalized linear models to binary outcomes. All models were adjusted for gender, age group (see Table 1 for breakdown), education, and marital status.

Differences between blacks and whites were examined in a two-step process. First, separate regression analyses were conducted for blacks and whites. Eighteen predictors in four domains (antisocial behavior, substance use/abuse, depressive symptoms, and psychotic symptoms) were tested in separate models containing the baseline covariates. Second, to test whether there were significant differences, models for the overall sample that included an interaction term for race and the individual predictors were run, and the significance of the interaction was tested. Preliminary analyses showed a significant three-way interaction between race, gender, and age group. Therefore, the race-stratified analyses included a term for the interaction of gender and age group, and the analyses that combined data for blacks and whites included a three-way interaction of race, gender, and age group. To guard against type I error, a Bonferroni adjustment was used to set the significance level at 0.003.

Results

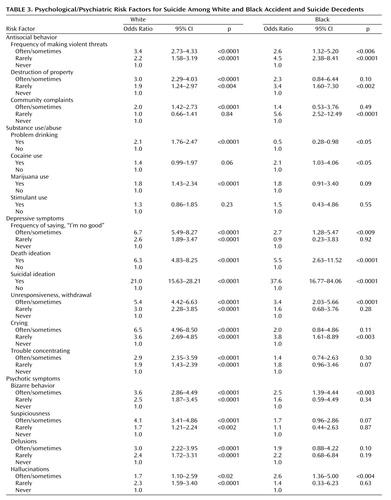

Table 3 shows the results of the stratified analyses. Four items distinguished suicides from accidents in both blacks and whites: death ideation, suicidal ideation, bizarre behavior, and withdrawn behavior. Use of marijuana was found to be a significant risk factor for suicide in whites.

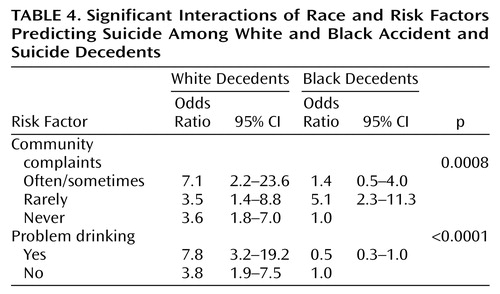

Table 4 shows the results for race-by-variable interactions. Reports of community complaints and problem drinking more strongly discriminated risk for suicide in whites than in blacks. No variable conferred greater risk in blacks than in whites.

Discussion

The 1993 National Mortality Followback Survey provided an unprecedented opportunity to identify risk factors for suicide in blacks and to examine potential race differences in suicide. A number of risk factors for suicide were common to both blacks and whites: withdrawn behavior, death ideation, suicidal ideation, and bizarre behavior. There are important differences, however. Whites who died by suicide were more likely to be problem drinkers, a finding that dovetails with the large literature on suicide and substance abuse (25, 26), and prior data on race differences in suicide risk factors (19). As well, the straightforward linear relationship between antisocial behavior (violent threats, destruction of property, community complaints) and suicide in whites was consistent with studies of predominantly white samples showing that violent behavior (27–29), antisocial behavior (30), and disruptive disorders (30, 31) confer risk for suicide and suicide attempts. However, our data suggest that the association between antisocial behavior and suicide in blacks warrants further empirical scrutiny. Whites who generated “frequent” community complaints, a proxy indicator for antisocial behavior, were at increased risk of suicide by more than sevenfold. For blacks, the association between community complaints and suicide was nonlinear. A low or high level of complaints did not confer risk, but a moderate level did (odds ratio=5.6). This finding may be ascribed to race differences in reporting of community complaints, but similar nonlinear patterns were found for destruction of property and making violent threats. Juon and Ensminger (32) found somewhat similar results.

There were some limitations to the current study. First, the 1993 National Mortality Followback survey, a secondary data set, was used in this study. Consequently, additional information that may have been obtained from practitioners was not available. Second, data collection relied on a phone interview with a proxy respondent. Third, the measures that were used to construct the various domains were brief. In addition, items in the questionnaire that inquired about participation in mental health services in the last year of life and history of emotional/mental health problems were dichotomous. More detailed information about mental health service utilization and mental health history was not available. Fourth, the smaller number of suicides in blacks (N=150) relative to whites (N=1,279) limits statistical power to a greater degree in blacks. These limitations are offset by the uniqueness of the data set, which offered an unprecedented opportunity to examine suicide in blacks and to include a comparison group of accident decedents.

In summary, depressive symptoms amplify suicide risk in blacks and whites, but there may be important race differences in the contributions to suicide risk of antisocial behavior and substance use/abuse. The current study underscores the need for examination of race differences in the relationship between antisocial behavior and suicide. It will also be essential to examine other variables that were unavailable in the National Mortality Followback Survey data set, particularly racism, perceived discrimination, and feelings of alienation from the dominant culture (33–36). Research on the interplay of these culturally relevant variables and established psychiatric risk factors may be warranted.

|

|

|

|

An earlier version of this paper was presented at the annual conference of the American Association of Suicidology, April 13, 2002, in Bethesda, Md. Received Oct. 1, 2002; revision received July 15, 2003; accepted July 24, 2003. From the Department of Psychiatry, Division of Psychology, University of Rochester Medical Center. Address reprint requests to Dr. Castle, Department of Psychiatry, Center for the Study and Prevention of Suicide, University of Rochester Medical Center, 300 Crittenden Blvd., Rochester, NY 14642; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by National Research Service Award Institutional Training grant T32 MH-18911 to the Department of Psychiatry, University of Rochester Medical Center.

1. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control: Years of Potential Life Lost Reports, 1999–2000: WISQARS Years of Potential Life Lost Reports, 2002. http://webapp.cdc.gov/sasweb/ncipc/ypll10.htmlGoogle Scholar

2. Minino AM, Smith BBL: National Vital Statistics Reports: Death: Preliminary Data for 2000. CDC, National Center of Health Statistics, 2000Google Scholar

3. Suicide among black youths—United States, 1980–1995. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 1998; 47:193–206Medline, Google Scholar

4. Shafii M, Carrigan S, Whittinghill JR, Derrick A: Psychological autopsy of completed suicide in children and adolescents. Am J Psychiatry 1985; 142:1061–1064Link, Google Scholar

5. Shafii M, Steltz-Lenarsky J, McCue Derrick A, Beckner C, Whittinghill R: Comorbidity of mental disorders in the post-mortem diagnosis of completed suicide in children and adolescents. J Affect Disord 1988; 15:227–233Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Brent DA, Perper JA, Goldstein CE, Kolko DJ, Allan MJ, Allman CJ, Zelenak JP: Risk factors for adolescent suicide. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988; 45:581–588Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Brent DA, Perper JA, Moritz G, Allman C, Friend A, Roth C, Schweers J, Balach L, Baugher M: Psychiatric risk factors for adolescent suicide: a case-control study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1993; 32:521–529Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Brent DA, Perper JA, Moritz G, Baugher M, Schweers J, Roth C: Suicide in affectively ill adolescents: a case-control study. J Affect Disord 1994; 31:193–202Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Shaffer D, Gould MS, Fisher P, Trautman P, Moreau D, Kleinman M, Flory M: Psychiatric diagnosis in child and adolescent suicide. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996; 53:339–348Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Gould MS, Fisher P, Parides M, Flory M, Shaffer D: Psychosocial risk factors of child and adolescent completed suicide. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996; 53:1155–1162Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Conwell Y, Lyness JM, Duberstein P, Cox C, Seidlitz L, DiGiorgio A, Caine ED: Completed suicide among older patients in primary care practices: a controlled study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2000; 43:23–29Google Scholar

12. Garlow SJ: Age, gender, and ethnicity differences in patterns of cocaine and ethanol use preceding suicide. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159:615–619Link, Google Scholar

13. Morrison LL, Downey DL: Racial differences in self-disclosure of suicidal ideation and reasons for living: implications for training. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol 2000; 6:374–386Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Watt TT, Sharp SF: Race differences in strains associated with suicidal behavior among adolescents. Youth and Society 2002; 34:232–256Crossref, Google Scholar

15. Foster T, Gillespie K, McClelland R, Patterson C: Risk factors for suicide independent of DSM-III-R axis I disorder: case-control psychological autopsy study in Northern Ireland. Br J Psychiatry 1999; 175:175–179Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Cheng A: Mental illness and suicide: a case-control study in East Taiwan. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995; 52:594–603Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Vijaykumar L, Rajkumar S: Are risk factors for suicide universal? a case-control study in India. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1999; 99:407–411Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Beautrais A: Suicides and serious attempt: two populations or one? Psychol Med 2001; 31:837–845Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Kung HC, Liu X, Juon HS: Risk factors for suicide in Caucasians and in African Americans: a matched case-control study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1988; 33:155–161Crossref, Google Scholar

20. National Mortality Followback Survey—Provisional Data, 1993. Hyattsville, Md, National Center for Health Statistics and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1998Google Scholar

21. Clark D, Horton-Deutsch S: Assessment in absentia: the value of the psychological autopsy method for studying antecedents of suicide and predicting future suicides, in Assessment and Prediction of Suicide. Edited by Maris RW, Berman AL, Maltsberger JR, Yufit RI. New York, Guilford, 1992, pp 144–182Google Scholar

22. Ohberg A, Penttila A, Lonnqvist J: Driver suicides. Br J Psychiatry 1997; 71:468–472Crossref, Google Scholar

23. Connolly JF, Cullen A, McTigue O: Single road traffic deaths: accident or suicide? Crisis 1995; 16:85–89Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. SUDAAN User’s Manual, Release 8.0. Research Triangle Park, NC, Research Triangle Institute, 2001Google Scholar

25. Beck AT, Steer RA: Clinical predictors of eventual suicide. J Affect Disord 1989; 17:203–209Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Harris EC, Barraclough B: Suicide as an outcome of mental disorders. Br J Psychiatry 1997; 170:205–228Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Borowsky I, Ireland M, Resnick MD: Adolescent suicide attempts: risk and protectors. Pediatrics 2001; 107:485–493Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. King RA, Schwab-Stone M, Flisher AJ, Greenwald S, Kramer R, Goodman SH, Lahey BB, Shaffer D, Gould MS: Psychosocial and risk behavior correlates of youth suicide attempts and suicidal ideation. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2001; 40:837–846Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Olsson GI: Violence in the lives of suicidal adolescents: a comparison between three matched groups of suicide attempting, depressed, and nondepressed high school students. Int J Adolesc Med Health 1999; 11:369–379Crossref, Google Scholar

30. Sourander A, Helstela L, Haavisto A, Bergoth L: Suicidal thoughts and attempts among adolescents: a longitudinal 8-year follow-up study. J Affect Disord 2001; 63:59–66Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Andrews JA, Lewinsohn PM: Suicidal attempts among older adolescents: prevalence and co-occurrence with psychiatric disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1992; 31:655–662Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Juon HS, Ensminger ME: Childhood, adolescent, and young adult predictors of suicidal behavior: a prospective study of African Americans. J Child Psychiatry 1997; 38:533–563Crossref, Google Scholar

33. Kessler R, Mickelson KD, Williams DR: The prevalence, distribution, and mental health correlates of perceived discrimination in the United States. J Health Soc Behav 1999; 40:208–230Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Gilvarry C, Walsh E, Samele C, Hutchinson G, Mallett R, Rabe-Hesketh S, Fahy T, van Os J, Murray R: Life events, ethnicity and perceptions of discrimination in patients with severe mental illness. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1999; 34:600–608Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Foster M: Positive and negative responses to personal discrimination: does coping make a difference? J Soc Psychol 2000; 140:93–106Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Branscombe N, Schmitt M, Harvey R: Perceiving pervasive discrimination among African Americans: implications for group identification and well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol 1999; 77:135–149Crossref, Google Scholar