Instability of Symptoms in Recurrent Major Depression: A Prospective Study

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Recurrent episodes of major depressive disorder are reported to have similar or stable characteristics across episodes. However, symptoms appear to be moderately stable only in consecutive depressive episodes or if episode severity is considered. The authors prospectively studied major depressive episodes occurring within 2 years to determine whether symptoms in the second episode could be predicted on the basis of symptoms in the first. METHOD: Inpatients (N=78) with major depressive disorder were rated with the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale during two separate episodes. Patients had a baseline assessment at index hospitalization and follow-up visits at 3, 12, and 24 months after discharge. Information regarding the presence of a major depressive episode, its duration, and its severity was documented. Baseline and follow-up data were analyzed by using Pearson correlations with and without adjustments for severity of depression. RESULTS: Subtype of depression appeared not to be stable. The most robust, although still weak, correlations across episodes were for anxiety and suicidal behavior. Only modest correlations were identified for a few depressive symptoms. CONCLUSIONS: The lack of robust consistency of symptoms or depressive subtype across episodes is striking given the requirement of five of nine predetermined symptoms for depression, increasing the chances of finding an association. These findings suggest that there is a superfamily of mood disorders with pleomorphic manifestations across major depressive episodes within individual patients with unipolar depression.

The lifetime prevalence of major depression is 10%–25% for women and 5%–12% for men, and recurrence of mood disorders is a major medical problem (DSM-IV, 1–6). In the United States, 85% of patients with an episode of major depression go on to have a recurrence (3), with an apparent increase in severity with each subsequent episode (5). Although the risk of relapse may decline with time (6), even for those who remain well for 5 years after an index episode the rate of recurrence is 58% (3). Despite the magnitude of the problem of recurrence, little attention has been focused on the symptom pattern in recurrent episodes of major depression.

Some studies suggest that patients experience similar symptoms in recurrent episodes (7–9). However, other work has shown that the stability of symptoms is moderate only in consecutive depressive episodes and low if the episodes are not consecutive (10, 11) or that symptoms are moderately stable if the severity of the episode is accounted for (12).

We prospectively determined the consistency of symptoms across two episodes of major depression occurring within a 2-year period in unipolar subjects to determine whether symptoms in the second episode could be predicted on the basis of the symptoms in the first episode. We predicted that symptoms would be similar from episode to episode in this relatively short time span.

Method

Subjects and Procedure

Inpatients (N=185) admitted for evaluation and treatment of depression to one of two university hospitals (in New York City and Pittsburgh) who met the DSM-IV criteria for a major depressive disorder, according to the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (13), were enrolled in the study. All patients either had severe symptoms interfering with daily functioning or were suicidal enough to warrant inpatient treatment. Exclusion criteria were neurological illness and active medical conditions. All subjects provided written informed consent as required by the institutional review boards of each hospital. Upon hospital admission (baseline), each patient had a physical examination, routine blood tests, and urine toxicology tests. Demographic characteristics and history of previous depressive episodes were documented by interviewers (including A.K.B.) with a minimum of a master’s degree in psychology or nursing. Depressive symptoms were rated with the 24-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (intraclass coefficient=0.94) (14).

After hospital discharge, the patients received treatment in the community and follow-up visits at 3, 12, and 24 months after discharge. At each follow-up visit, the subject was contacted by the same clinician who had conducted the baseline evaluation. Information regarding the presence or absence of a major depressive episode and its duration since the last assessment was documented. The Hamilton Depression Rating Scale was also administered at each follow-up visit. We compared the Hamilton depression scores of the subgroup of patients (N=78) who experienced a recurrence of major depression at any one of the follow-up visits with the scores during the index episode. None of these 78 subjects met the criteria for major depressive episode for at least 2 months before the onset of the recurrent episode. The use of the Hamilton depression scale to assess symptoms across episodes allowed for comparison with data in the previously published literature.

Data Analysis

Clinical and demographic information was analyzed by using Student’s t test for continuous variables and the chi-square statistic for categorical variables. The clinical and demographic data for the subgroup of interest were compared to those for depressed patients who had not experienced a recurrence during the 2-year follow-up period and to those for depressed patients who had a recurrence but were not in a major depressive episode at the time of any of the follow-up visits.

Baseline and follow-up data were analyzed by using four related approaches. First, the relationships between scores on the 24 items of the Hamilton depression scale during the baseline episode and the scores during the first assessed follow-up episode were examined by using Pearson’s correlations. We used correlations in order to detect the presence of an association between symptoms in the two episodes and the strength of the relationship. A Bonferroni correction consisted of dividing the p value by the number of comparisons conducted in each analysis. These correlations were conducted on the raw data and on the data adjusted for severity of depression. We adjusted for severity because of the observation of Young et al. (12) that correlations between symptoms in two episodes were more robust if adjustment was made for episode severity.

The following strategies were used for data reduction and to facilitate clinical interpretation of the statistical analyses. In order to determine whether symptoms of major depression showed stability across episodes, we assigned Hamilton depression scale items to each of the nine DSM-IV symptoms and added a 10th symptom category for anxiety at both the baseline and follow-up episodes (Table 1). The relationships between these 10 symptoms at baseline and at the follow-up episode were examined by Pearson correlations. Both raw data and data subjected to two different adjustments for severity of depression at each time point were examined. In the first strategy used to adjust for severity of depression, each item score was divided by the total sum for the 10 symptoms for each subject. In the second approach, each item score was divided by the total Hamilton score for each subject. We conducted a bootstrap analysis of the Pearson correlations of these 10 symptoms to adjust for multiple comparisons (15). The bootstrap analysis yielded the same significance levels (p values) as were obtained by using a Bonferroni correction. Therefore, for all other Pearson correlational analyses, Bonferroni corrections were applied.

We also analyzed the Hamilton depression scale items by using dimensional categories derived from a discriminant function analysis based on the work of Overall and Rhoades (16). This discriminant function analysis generated five symptom clusters—anxious, suicidal, somatizing, vegetative, and paranoid—based on the item that loaded most heavily onto each category. The five dimensional categories generated for both the baseline and follow-up episodes were then subjected to Bonferroni-corrected Pearson correlations.

The items of the Hamilton depression scale were also collapsed into three clinical subscales measuring atypical symptoms, melancholic symptoms, and psychotic symptoms. The items designated atypical were hypersomnia, increased appetite or weight gain, and feelings of worthlessness. The items designated melancholic were those measuring early, middle, and late insomnia, ability to complete work and activities, psychomotor retardation, psychic anxiety, gastrointestinal somatic symptoms (appetite loss), weight loss, and diurnal variation. The items designated psychotic were paranoid symptoms and any items with ratings of 4 from the measures of guilt feelings, hypochondriasis, helplessness, hopelessness, and feelings of worthlessness. This generated three subscales for each episode, and the three subscales were examined by using Bonferroni-corrected paired t tests. In addition, we calculated kappa coefficients for the concordance of psychotic subtype at baseline and follow-up.

Finally, we conducted a multivariate multiple regression to assess the possible effect of course of illness in the subjects. The baseline scores for each of the 10 symptoms (nine DSM-IV symptoms of depression plus anxiety) and the number of previous depressive episodes were the independent variables, and the follow-up scores for the 10 symptoms were the dependent variables.

Results

The clinical and demographic characteristics of the subgroup with recurrent major depressive episodes (N=78) did not differ from those of depressed patients who had no recurrence during the 2-year follow-up period (N=41) or those of the depressed patients who had a recurrence but were not in a major depressive episode at the time of any of the follow-up visits (N=66) (data available on request). Characteristics of those with a recurrence are shown in Table 2.

Hamilton Scale Items Across Episodes

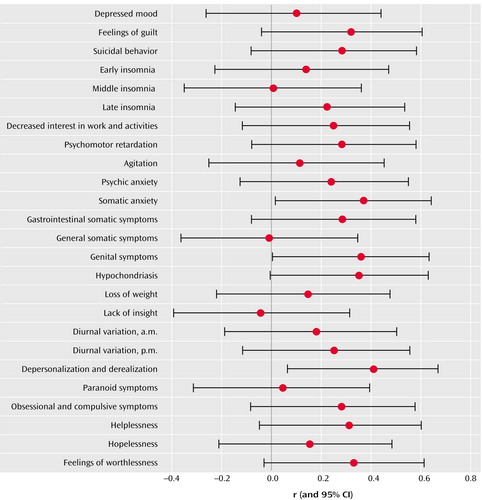

For the patients who were experiencing a recurrence at one of the follow-up assessments, the Pearson correlations between scores on the 24 items of the Hamilton depression scale at baseline and at follow-up did not identify significant correlations between the individual raw items during the two episodes (Figure 1). However, once the ratings were adjusted for severity of symptoms by dividing each item score by the total Hamilton scale score, the correlations between baseline and follow-up ratings became statistically significant for depersonalization and derealization (r=0.41, t=3.77, Bonferroni-corrected p=0.009), somatic anxiety (r=0.37, t=3.33, Bonferroni-corrected p=0.04), and genital symptoms (r=0.36, t=3.22, Bonferroni-corrected p=0.05) (N=78 for all correlations). The range of correlations for the 24 items was from r=–0.04 to r=0.41, with p values from 0.009 to 1.00 (truncated at 1.00 after Bonferroni correction) (Figure 1).

DSM-IV Depressive Symptoms and Anxiety Across Episodes

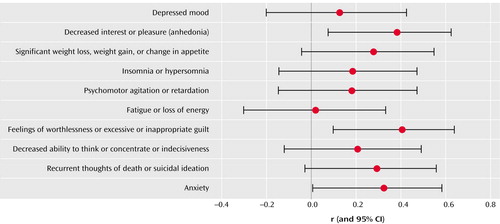

Similar to the analysis of the scores for the 24 items of the Hamilton depression scale, Pearson’s correlations subjected to a bootstrap analysis to adjust for multiple comparisons showed that the raw subscale scores at baseline for the nine DSM-IV symptoms of major depressive episode and the additional symptom of anxiety were not correlated with any scores at follow-up. We also examined the relationship between the 10 symptoms at baseline and follow-up by dividing by the sum of the scores for the 10 symptoms as an adjustment for overall syndrome severity for each subject and subjecting the p values to Bonferroni correction. This produced modest correlations between baseline and follow-up scores that were significant for anhedonia (r=0.39, t=3.58, p=0.006), guilt feelings and feelings of worthlessness (r=0.41, t=3.81, p=0.003), and anxiety (r=0.33, t=2.95, p=0.05) (N=78) (Figure 2). The correlation between episodes for suicidal ideation/behavior did not reach statistical significance (r=0.30, t=2.64, p=0.10). The correlations for these 10 symptoms at baseline and follow-up adjusted for overall severity of depression ranged from r=0.02 to 0.41, with Bonferroni-corrected p values from 0.006 to 1.00 (Figure 2).

A multiple regression analysis with the 10 baseline raw scores and the number of previous depressive episodes as the independent variables and the 10 follow-up scores as the dependent variables showed that the number of depressive episodes did not predict follow-up scores. This suggests that evolution of the depressive illness or progression of illness as measured by frequency of episodes is not a factor affecting the consistency of symptoms across the two episodes studied here.

Hamilton Scale Dimensional Categories Across Episodes

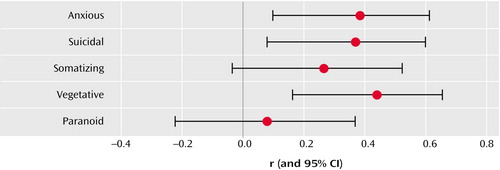

The Pearson correlations of Overall and Rhoades’s five dimensional categories of the Hamilton scale items at baseline and at follow-up revealed that the vegetative (r=0.44, t=4.14, Bonferroni-corrected p<0.001), anxious (r=0.39, t=3.51, Bonferroni-corrected p=0.004), and suicidal (r=0.37, t=3.36, Bonferroni-corrected p=0.006) categories at baseline and follow-up were modestly correlated after correction for episode severity (N=78). The somatic (r=0.27, t=2.33, Bonferroni-corrected p=0.11) and paranoid (r=0.08, t=0.68, Bonferroni-corrected p=1.00) categories were not (Figure 3).

Depressive Subtype Across Episodes

The severity of atypical, vegetative (or melancholic), or psychotic aspects of depression did not appear to be consistent from baseline to the follow-up episode. Paired t tests showed that the scores, tabulated from the Hamilton depression scale at baseline and follow-up, were significantly different for atypical symptoms (t=4.56, df=77, p=0.001), neurovegetative symptoms (t=4.65, df=77, p=0.001), and psychotic symptoms (t=2.93, df=77, p=0.004). These differences remained after Bonferroni correction (multiplying by 3 to adjust for the three comparisons conducted). In addition, the kappa coefficient for the association of psychotic depression at baseline and follow-up was low (kappa=0.08), although it was not statistically significant.

Discussion

The most robust correlations across episodes were for anxiety and suicidal behavior and were confirmed by two separate methods: the five categories of Overall and Rhoades and the DSM-IV symptom criteria for major depressive episode, adjusted for the severity of the episode. However, even with these two methods, the correlations were modest (r<0.45). Although the Overall and Rhoades vegetative category was related in the two episodes, the most heavily loaded item on the Hamilton depression scale was middle insomnia. Weight or appetite changes had only a weak effect. In contrast, analyses of symptoms showed sleep disturbance to be unrelated between episodes. The Overall and Rhoades categories are difficult to interpret, as the factors are based on statistical relationship, not a priori clinical relationships. Also, episodes classified by subtype (atypical, melancholic, or psychotic) showed no relationship between baseline and follow-up.

Consistency of Symptoms

Using an expanded Hamilton depression scale to assess 33 women with relapse of major depressive disorder, Paykel et al. (17) found moderate correlations between baseline and relapse for nine of 28 items: depressed mood, diurnal variation, hopelessness, obsessional symptoms, psychic anxiety, somatic anxiety, anorexia, increased appetite, and irritability. Except for irritability, the product-moment correlations were less than 0.5. A Bonferroni correction would uphold only the correlation of irritability between baseline and relapse. Acknowledging the short interval between measures, the authors nonetheless concluded that some consistency exists in symptom pattern. We found significant, although modest, correlations of symptom ratings between baseline and follow-up episodes for somatic anxiety, genital symptoms, and depersonalization and derealization. Thus, only one correlated symptom coincides. This difference may reflect that study’s restriction to relapses and not new episodes (17).

Concordance in the direction of weight changes across two episodes of major depressive disorder in medication-free patients was found in a study that used both prospective and retrospective data (18). The data for all of our subjects were gathered prospectively, and although we had no data on the subjects’ actual weight, we found no correlation between Hamilton depression scale appetite measures across episodes.

Syndrome severity may explain changes in symptom pattern. Young et al. (12) found that with similar depression severity across two episodes, the stability of 12 nonoverlapping symptoms was moderate (median kappa, 0.53). When severity differed, the kappas were much lower, indicating that episodic concordance of symptoms depends on severity. Moreover, a symptom that was present in the less severe episode was unlikely to be absent in the more severe one (12).

We underscore the modest strength of the correlations that we, and others, have identified and the low number of depressive symptoms for which these correlations hold. Impressions of clinical similarity may stem from an inclination to seek and identify patterns and to downplay variations in individual symptoms, in order to establish diagnoses. The lack of robust consistency is striking in that, by definition, we require subjects to meet criteria for depression and thus have at least five of nine symptoms, increasing our chances of finding an association.

Consistency of Depressive Subtype

We found no relationship between subtypes of depression across episodes. Previous studies of subtype stability across episodes suggest, at best, a weak correlation between subtypes. Winokur et al. (11) found psychotic symptoms less often in subsequent episodes, suggesting that psychosis recurs inconsistently and that the illness evolves into a less psychotic form over time. Coryell et al. (10) found greater subtype stability across contiguous episodes than across noncontiguous ones. The psychotic subtype had the most stability, with a four- to 15-fold increased risk of psychosis at the time of recurrence, although the kappa was only 0.57 (10). Young et al. (19) examined the Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC) endogenous depression subtype and found only a 0.50 probability that subsequent episodes were again endogenous.

Others have reported higher concordance between depression episodes. Nierenberg et al. (9) categorized symptoms as “positive” or typical neurovegetative, such as insomnia and decreased appetite, or “reversed,” such as hypersomnia and weight gain. In 32 patients with major depression, 60% with positive symptoms at baseline had positive symptoms at relapse, while 92% with reversed symptoms had reversed symptoms at relapse. However, patients with both relapse and recurrence were included, and the follow-up time was relatively brief. Nelson and Charney (7) found that 89% of 54 delusional subjects had a prior delusional episode, compared to 12% of 66 nondelusional patients, which, paired with differential treatment response, suggested that delusional depressions are different from nondelusional ones. A study of 61 patients with psychotic unipolar depression indicated that 93% had a psychotic depressive episode either before or after the index admission, although no episode intervals were reported (8). Also, the focus on episodes requiring hospital admission suggests that milder nonpsychotic episodes possibly went undocumented. Moreover, once a patient is identified as having had a psychotic depression, psychotic symptoms may be assessed more vigorously. Our study used semistructured interviews and the Hamilton depression scale to minimize the potential for this type of bias. Leckman et al. (20) ascertained the consistency of depression by examining family concordance for subtype. Among 133 patients with unipolar depression and their first-degree relatives, many patients met the RDC criteria for multiple subtypes: endogenous, autonomous, melancholic, or delusional. The strongest concordance, 37%, was among relatives of delusionally depressed subjects (20), suggesting remarkably low concordance of both subtype and symptoms. This is even more striking in that the episodes were identified on the basis of the presence of a minimum number of depressive symptoms; episodes failing to meet certain criteria were not rated or counted. Thus, despite the identification of episodes on the basis of a relatively small number of depressive symptoms, concordance remained low.

Implications of Symptom Instability

The stability of symptoms or depressive episode subtype across episodes has implications from phenomenological, prognostic, and treatment standpoints. Concordance of symptom presence or subtype between episodes suggests that depressive subtypes are different diseases, possibly with unique psychobiological underpinnings, while variations, or subtypes, of mood disorders in the same subject suggest a single major type of mood disorder that is pleomorphic. This view parallels Bleuler’s observations of schizophrenia (21), as he considered hebephrenic, catatonic, paranoid, and other types of schizophrenia in the same subject at different times as different manifestations of the same illness. Similarly, as different forms of mood disorder can occur at different times in the same subject, they can be conceptualized as constituting part of the same family of illness. On the other hand, if the presentation consistently changes from initially atypical depression to psychotic depression and then to the melancholic type, we might infer an evolution of the illness or a sequential presentation of different phases of the same illness. A longer-term follow-up study over many major depressive episodes is required to determine this.

Consistency of subtypes across major depressive episodes has implications for posited specific treatment response (22). Certain types of depression appear to respond preferentially to specific treatments (22). However, if individuals have consecutive episodes with differing symptoms, maintenance treatment or reinstitution of treatment in a recurrence may not optimally require the use of a medication that was successful in the previous episode.

Comments

This study had some limitations. The requirement that subjects have a recurrence of depression at the time of the 3-, 12-, or 24-month follow-up may have biased the group of subjects analyzed. Not only did we by definition not include those who had a recurrence after 2 years, but also the subjects studied may be different from those having shorter episodes that were not present at any of the follow-up assessments. However, we compared the subjects who did not have an episode at any follow-up point to our study group, and they do not seem to have been generally different demographically or clinically.

Furthermore, the subjects were inpatients, and the findings may not apply to milder forms of depression. In addition, although we recorded atypical and melancholic symptoms, we did not have actual classification of the depressive episode at the follow-up assessment in terms of atypical or melancholic subtype.

In summary, we could not find evidence that the symptoms or subtypes of depression are stable from one episode to another. The absence of such evidence indicates that there may be a single superfamily of mood disorder that is pleomorphic in its manifestations across episodes within individual patients. This conclusion has important potential implications for understanding the basis of classification of subtypes of major depression, for treatment, and for family and genetic studies. Further studies are needed to determine whether the episode form of major depressive disorder evolves according to a consistent pattern over the life cycle.

|

|

Received Jan. 29, 2003; revision received June 11, 2003; accepted June 13, 2003. From the Department of Neuroscience, New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York; the Department of Psychiatry, Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, and the Department of Psychiatry, University of Pittsburgh. Address reprint requests to Dr. Oquendo, Department of Psychiatry, Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, 1051 Riverside Dr., New York, NY 10032; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression, the American Foundation of Suicide Prevention, and NIMH grants MH-46745 and MH-40695.

Figure 1. Correlations Between Scores on Individual Items of the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale During Two Separate Episodes of Major Depression in 78 Patientsa

aCorrelations were adjusted for the severity of the depressive episode. Significance levels were adjusted by the Bonferroni procedure.

Figure 2. Correlations Between DSM-IV Depressive Symptoms Plus Anxiety During Two Separate Episodes of Major Depression in 78 Patientsa

aCorrelations were adjusted for the severity of the depressive episode. Significance levels were adjusted by the Bonferroni procedure.

Figure 3. Correlations Between Depressive Dimensions During Two Separate Episodes of Major Depression in 78 Patientsa

aDimensional categories of the items in the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale were derived from a discriminant function analysis based on the work of Overall and Rhoades (16). Correlations were adjusted for the severity of the depressive episode. Significance levels were adjusted by the Bonferroni procedure.

1. Kessler RC, Crum RM, Warner LA, Nelson CB, Schulenberg J, Anthony JC: Lifetime co-occurrence of DSM-III-R alcohol abuse and dependence with other psychiatric disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1997; 54:313–321Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Weissman MM, Bruce ML, Leaf PJ, Florio LP, Holzer C: Affective disorders, in Psychiatric Disorders in America: The Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study. Edited by Robins LN, Regier DA. New York, Free Press, 1998, pp 1351–1387Google Scholar

3. Mueller TI, Leon AC, Keller MB, Solomon DA, Endicott J, Coryell W, Warshaw M, Maser JD: Recurrence after recovery from major depressive disorder during 15 years of observational follow-up. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:1000–1006Abstract, Google Scholar

4. Frank E, Kupfer DJ, Perel JM, Cornes C, Jarrett DB, Mallinger AG, Thase ME, McEachran AB, Grochocinski VJ: Three-year outcomes for maintenance therapies in recurrent depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1990; 47:1093–1099Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Maj M, Veltro F, Pirozzi R, Lobrace S, Magliano L: Pattern of recurrence of illness after recovery from an episode of major depression: a prospective study. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:795–800Link, Google Scholar

6. Keller MB, Lavori PW, Lewis CE, Klerman GL: Predictors of relapse in major depressive disorder. JAMA 1983; 250:3299–3304Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Nelson JC, Charney DS: The symptoms of major depressive illness. Am J Psychiatry 1981; 138:1–13Link, Google Scholar

8. Helms PM, Smith RE: Recurrent psychotic depression: evidence of diagnostic stability. J Affect Disord 1983; 5:51–54Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Nierenberg AA, Pava JA, Clancy KP, Rosenbaum JF, Fava M: Are neurovegetative symptoms stable in relapsing or recurrent atypical depressive episodes? Biol Psychiatry 1996; 40:691–696Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Coryell W, Winokur G, Shea T, Maser JD, Endicott J, Akiskal HS: The long-term stability of depressive subtypes. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:199–204Link, Google Scholar

11. Winokur G, Scharfetter C, Angst J: Stability of psychotic symptomatology (delusions, hallucinations), affective syndromes, and schizophrenic symptoms (thought disorder, incongruent affect) over episodes in remitting psychoses. Eur Arch Psychiatry Neurol Sci 1985; 234:303–307Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Young MA, Fogg LF, Scheftner WA, Fawcett JA: Concordance of symptoms in recurrent depressive episodes. J Affect Disord 1990; 20:79–85Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. First MB, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV—Patient Edition (SCID-P). Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1995Google Scholar

14. Hamilton M: A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1960; 23:56–62Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Efron B, Tibshirani RJ: An Introduction to the Bootstrap. New York, Chapman & Hall, 1993Google Scholar

16. Overall JE, Rhoades HM: Use of the Hamilton rating scale for classification of depressive disorders. Compr Psychiatry 1982; 23:370–376Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Paykel ES, Prusoff BA, Tanner J: Temporal stability of symptom patterns in depression. Br J Psychiatry 1976; 128:369–374Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Stunkard AJ, Fernstrom MH, Price A, Frank E, Kupfer DJ: Direction of weight change in recurrent depression: consistency across episodes. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1990; 47:857–860Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Young MA, Keller MB, Lavori PW, Scheftner WA, Fawcett JA, Endicott J, Hirschfeld RMA: Lack of stability of the RDC endogenous subtype in consecutive episodes of major depression. J Affect Disord 1987; 12:139–143Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Leckman JF, Weissman MM, Prusoff BA, Caruso KA, Merikangas KR, Pauls DL, Kidd KK: Subtypes of depression: family study perspective. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1984; 41:833–838Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Bleuler E: Dementia Praecox or the Group of Schizophrenias. New York, International Universities Press, 1950Google Scholar

22. Quitkin FM, Stewart JW, McGrath PJ, Tricamo E, Rabkin JG, Ocepek-Welikson K, Nunes E, Harrison W, Klein DF: Columbia atypical depression: a subgroup of depressives with better response to MAOI than to tricyclic antidepressants or placebo. Br J Psychiatry Suppl 1993; 21:30–34Medline, Google Scholar