Unipolar Mania Over the Course of a 20-Year Follow-Up Study

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Using data from a longitudinal study of the mood disorders, the investigators address the phenomenon of unipolar mania. METHOD: Subjects diagnosed as having Research Diagnostic Criteria mania at intake into the study were prospectively followed for up to 20 years. RESULTS: Twenty-seven subjects had the diagnosis of unipolar mania at the time they entered the study and had no history of major depression before enrolling in the study. Seven of these subjects did not suffer any episodes of major depression during the 15- to 20-year follow-up. CONCLUSIONS: These data support the diagnostic validity of unipolar mania.

Nearly every study of unipolar mania has used retrospective methods. In the one prospective study of unipolar mania to our knowledge that has been published (1), the average length of follow-up was 5.6 years. Findings based on retrospective methods have led some authorities to question the existence of unipolar mania as a separate diagnostic entity.

Method

From 1978 to 1981, the NIMH Collaborative Depression Study—a prospective, longitudinal, observational study of the mood disorders—recruited individuals seeking treatment for major depression, mania, schizoaffective mania, or schizoaffective depression at five U.S. academic medical centers (in Boston, Chicago, Iowa City, New York, and St. Louis). Inclusion criteria included age of at least 17 years, IQ greater than 70, ability to speak English, white race (genetic hypotheses were tested), and no signs of a mood or psychotic disorder secondary to a general medical condition. After the study was completely described to subjects, written informed consent was obtained from all who participated.

At intake into the study, current and past psychiatric history were assessed with the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (2). Diagnoses were then made according to Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC) (3).

A total of 163 patients with bipolar I disorder entered the Collaborative Depression Study, including 14 who enrolled during an episode of mania and who had no previous history of major or minor depression. Sixty-six subjects with schizoaffective disorder, mainly affective subtype, also entered the Collaborative Depression Study, and this group included 13 subjects who were experiencing an episode of mania and had no previous history of major or minor depression. (Subjects with RDC-diagnosed schizoaffective disorder, mainly affective subtype, were included in the present analyses because the RDC definition of schizoaffective mania, mainly affective subtype [3], is nearly identical to the definition of bipolar I mania in DSM-IV.)

For the purposes of the present study, a minimum of 15 years of prospective follow-up was required for each subject. Follow-up assessments using the Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation (4) were completed every 6 months for the first 5 years of the study and annually thereafter. The Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation assesses level of psychopathology on a weekly basis. At each interview, the rater identified chronological anchor points (such as birthdays and holidays) from the time of the last interview to assist the subject in remembering those times when significant clinical improvement or deterioration occurred. Whenever possible, assessments with the Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation were corroborated with data from medical records. The Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation also assesses treatment, which was not randomly assigned by design and not controlled by anyone connected with the study.

Results

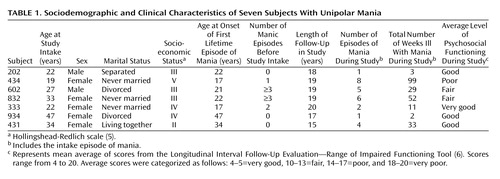

Of the 27 subjects with mania at study intake and no history of major depression or minor depression before enrolling in the study, seven did not suffer any episodes of major depression during prospective follow-up. Of these seven, five did not suffer any episodes of minor depression during follow-up. Table 1 shows the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics for the seven subjects with unipolar mania.

None of the seven subjects had a history of hypomania before enrolling in the study. Subjects 431, 602, 832, and 934 each had a positive family psychiatric history, defined as one or more first-degree relatives with a history of major depression, mania, schizoaffective depression, or schizoaffective mania according to Family History—Research Diagnostic Criteria (7).

One subject (number 202) was enrolled at the New York site, one (number 333) at St. Louis, and the remaining five subjects at the Iowa site. All seven subjects were enrolled as inpatients. Scores on the Global Assessment Scale for the week before hospital admission ranged from 20 to 45, indicating severe symptoms and functional impairment. Five subjects (numbers 202, 434, 602, 832, and 431) had symptoms of psychosis at study intake.

During prospective follow-up, subject 434 suffered eight episodes of hypomania lasting a total of 15 weeks, subject 832 suffered six episodes of hypomania lasting a total of 12 weeks, and subject 431 suffered two episodes of hypomania lasting a total of 5 weeks. Subjects 333 and 934 each suffered a single episode of minor depression.

Psychosocial functioning (work, interpersonal relationships, recreation, and satisfaction) was assessed with the Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation every 6 months during the first 5 years of the study and annually thereafter. For each of these assessments of psychosocial functioning, a single summary score was generated by using the Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation—Range of Impaired Functioning Tool (6). The mean average of these summary scores was then calculated and categorized as shown in Table 1.

For each subject, the percent of follow-up weeks for which the subject was treated with any dose of a mood stabilizer was calculated. Subjects 333, 431, 434, 602, and 832 were treated with a mood stabilizer for more than 90% of the follow-up period, and subjects 202 and 934 were treated for less than 5% of the follow-up period. Two subjects received antidepressants, subject 434 for 11 weeks and subject 832 for 15 weeks.

One subject attempted suicide during follow-up. At this time, all seven subjects remain alive.

Discussion

Although the DSM-IV definition of bipolar I disorder allows for individuals with unipolar mania, DSM-IV does not mention unipolar mania as a longitudinal course specifier. The results of this study provide evidence that unipolar mania represents a valid diagnostic category within bipolar I disorder.

Manic recurrences developed in the five subjects who were treated with a mood stabilizer more than 90% of the time during follow-up, but no manic recurrences developed in the two subjects who got very little treatment with a mood stabilizer during follow-up. This suggests that treatment does not explain the absence of depressive episodes.

Unipolar mania was rare in the present study. This is consistent with Kraepelin’s landmark study (8), which found that unipolar mania is a genuine but relatively rare diagnostic entity.

Five of the seven subjects with unipolar mania were enrolled at the Iowa site. One partial explanation for this may be the rural setting of this site, in contrast to the urban setting of the other four study sites.

The present study does not include any comparisons with bipolar I subjects who had a history of depression. This is due to the small number of subjects with unipolar mania and the focus of the present study on the diagnostic validity of unipolar mania.

The validity of unipolar mania has implications for efforts to understand the biological underpinnings of manic-depressive illness. If unipolar mania is a valid diagnostic entity, any theory that attempts to explain the physiological and anatomical basis of bipolar I disorder will need to account for unipolar mania.

|

Received June 20, 2002; revision received March 27, 2003; accepted April 7, 2003. From the National Institute of Mental Health Collaborative Program on the Psychobiology of Depression—Clinical Studies; the Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior, Brown University, Providence, R.I.; the Department of Psychiatry, Cornell University, New York; the Department of Research and Training, New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York; and the Department of Psychiatry, University of Iowa, Iowa City. Address correspondence to Dr. Solomon, Mood Disorders Program, Department of Psychiatry, Rhode Island Hospital, 593 Eddy St., Providence, RI 02903-4970; [email protected] (e-mail). The National Institute of Mental Health Collaborative Program on the Psychobiology of Depression—Clinical Studies is conducted with the participation of the following investigators: M.B. Keller, M.D. (Chairperson, Providence, RI); W. Coryell, M.D. (Co-Chairperson, Iowa City, IA); T.I. Mueller, M.D., D.A. Solomon, M.D. (Providence, RI); J. Fawcett, M.D., W.A. Scheftner, M.D. (Chicago); J. Haley (Iowa City, IA); J. Endicott, Ph.D., A.C. Leon, Ph.D., J. Loth, M.S.W. (New York); and J. Rice, Ph.D., T. Reich, M.D. (St. Louis). Other contributors include H.S. Akiskal, M.D., N.C. Andreasen, M.D., Ph.D., P.J. Clayton, M.D., J. Croughan, M.D., R.M.A. Hirschfeld, M.D., L. Judd, M.D., M.M. Katz, Ph.D., P.W. Lavori, Ph.D., J.D. Maser, Ph.D., M.T. Shea, Ph.D., R.L. Spitzer, M.D., and M.A. Young, Ph.D. Deceased: G.L. Klerman, M.D., E. Robins, M.D., R.W. Shapiro, M.D., and G. Winokur, M.D. This manuscript has been reviewed by the Publication Committee of the Collaborative Depression Study and has its endorsement.

1. Shulman KI, Tohen M: Unipolar mania reconsidered. Br J Psychiatry 1994; 164:547–549Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Endicott J, Spitzer RL: A diagnostic interview: the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1978; 35:837–844Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Spitzer RL, Endicott J, Robins E: Research Diagnostic Criteria: rationale and reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1978; 35:773–782Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Keller MB, Lavori PW, Friedman B, Nielsen E, Endicott J, McDonald-Scott P, Andreasen NC: The Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation: a comprehensive method for assessing outcome in prospective longitudinal studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1987; 44:540–548Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Hollingshead AB, Redlich FC: Social Class and Mental Illness: A Community Study. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1958, pp 387–397Google Scholar

6. Leon AC, Solomon DA, Mueller TI, Endicott J, Posternak M, Judd LL, Schettler PJ, Akiskal HS, Keller MB: A brief assessment of psychosocial functioning of subjects with bipolar I disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis 2000; 188:805–812Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Andreasen NC, Endicott J, Spitzer RL, Winokur G: The family history method using diagnostic criteria: reliability and validity. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1977; 34:1229–1235Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Kraepelin E: Manic-Depressive Insanity and Paranoia. Translated by Barclay RM, edited by Robertson GM. Edinburgh, E & S Livingstone, 1921, pp 185, 188Google Scholar