Do Patients With Schizophrenia Consciously Recollect Emotional Events Better Than Neutral Events?

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The influence of the emotional valence of words on conscious awareness was assessed in patients with schizophrenia. METHOD: The remember/know procedure was used to test 24 patients with schizophrenia and 24 normal comparison subjects. RESULTS: Patients’ “remember” responses and conscious recollection were more frequent for emotional words than for neutral words. In contrast, the levels of “know” responses and familiarity were independent of emotional words. CONCLUSIONS: Patients with schizophrenia consciously recollected emotional words better than neutral words.

Conscious awareness associated with recognition memory comprises two distinct subjective states that may be investigated experimentally with the remember/know procedure (1). In a recognition task, subjects are asked to report their subjective state of awareness at the time that they recognize each individual item. They are instructed to give a “remember” response if they consciously recollect something that they experienced when they learned the item—that is, if they mentally relive the learning episode. They are instructed to give a “know” response if recognition is accompanied by feelings of familiarity in the absence of any conscious recollection. In normal subjects, emotions influence the two states of awareness differentially: “remember” responses but not “know” responses are more frequent for emotional than for neutral events (2).

Use of the remember/know procedure has shown that patients with schizophrenia exhibit lower levels of “remember” but not “know” responses (3). Although disturbances of emotion are a major aspect of schizophrenia (4), studies that have used the procedure have been conducted with neutral stimuli, leaving unexplored the states of awareness that accompany memory for emotional events. We used the remember/know procedure to assess the influence of emotional words on conscious awareness in patients with schizophrenia. Results were analyzed according to the mutually exclusive categories of “remember” and “know” responses and in reference to the model developed by Yonelinas et al. (5), which posits that processes of conscious recollection and familiarity underlying the subjective states of awareness are independent. Because patients with schizophrenia remain sensitive to the emotional salience of words (e.g., reference 6), we predicted that despite lower overall levels, “remember” responses and conscious recollection should be enhanced by emotional words.

Method

Twenty-four patients (15 men and nine women) participated in the study. They fulfilled DSM-III-R criteria for schizophrenia. All of the patients were clinically stable. They were receiving long-term neuroleptic treatment, administered in a standard dose. Eleven patients were receiving an antiparkinsonian treatment. The patients were not receiving benzodiazepines at the time of testing. Mean scores on the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale, the Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (7), and the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (8) were 43.3 (SD=14.8), 42.7 (SD=12.0), and 64.1 (SD=14.3), respectively.

The normal comparison group comprised 24 subjects (15 men and nine women). The patients and comparison subjects had no history of traumatic brain injury, epilepsy, alcohol or substance abuse, or other neurological problems, as indicated by a clinical examination carried out by two trained psychiatrists (M.K. and N.K.). They did not differ in age (32.4 years, SD=6.8, and 31.0 years, SD=7.8, respectively) (t=0.51, df=46, p=0.61) or education (11.2 years, SD=5.6, and 11.2 years, SD=2.8) (t=0.88, df=46, p=0.42). All participants provided informed written consent.

Words were selected on the basis of their emotional valence. Two lists of 30 words were used, each composed of 10 positive, 10 negative, and 10 neutral words, and equated according to concreteness, frequency, and length and randomly mixed. In each group of subjects, one-half received one study list and the rest, the other. During the study phase, 30 words were presented on flash cards at the rate of 10 seconds per word. The subjects were asked to read the words aloud, to remember them, and to perform an orienting task that required them to rate the words on a 100-mm visual analogue scale according to their subjective feelings of pleasantness and unpleasantness. For technical reasons, ratings were missing for one patient and one comparison subject.

The recognition test was administered 15 minutes after the end of the learning phase and consisted of all 60 words. The subjects were asked to recognize words from the study list, then they were told to make a “remember” or “know” judgment. The instructions given followed closely those specified by Huron et al. (3). The subjects were asked to give a “remember” response if they could consciously recollect details of the word’s study presentation and a “know” response if the word felt familiar but they could not recollect its earlier presentation.

The proportions of “remember” and “know” responses for the old and new items were computed as a function of word type by dividing the number of responses by the total number of possible responses. “Remember” and “know” responses were also analyzed according to the model of Yonelinas et al. (5) to estimate processes of conscious recollection and familiarity (Fd′). Variables were subjected to separate analyses of variance (ANOVAs), with word type as a within-subject factor and group as a between-subject factor. Whenever the result of an analysis was significant, Student’s t tests and paired t tests were performed to localize differences.

Results

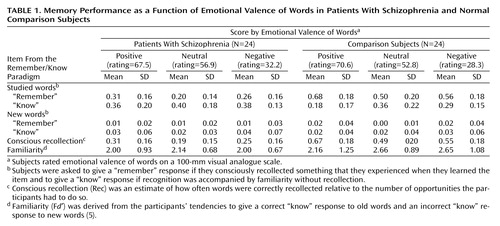

Both groups discriminated among positive, negative, and neutral words (F=91.2, df=2, 88, p<0.0001) and did so to the same extent, as indicated by a nonsignificant group effect and a nonsignificant interaction effect between group and word type (Table 1). An ANOVA performed on “remember” responses yielded a significant group effect (F=55.4, df=1, 46, p<0.0001), with patients giving fewer “remember” responses than normal comparison subjects. There was a significant effect for word type (F=29.1, df=2, 92, p<0.0001) but no interaction between word type and group. In both groups, the proportion of “remember” responses was significantly higher for positive than for negative words, which in turn was significantly higher than for neutral words. For “know” responses, there was a significant group effect (F=5.3, df=1, 46, p<0.03), with patients giving more “know” responses than comparison subjects. There was a significant effect of word type (F=11.4, df=2, 92, p<0.0001) and a significant interaction between word type and group (F=4.32, df=2, 92, p<0.02). This interaction was because for the patients, “know” responses did not vary as a function of word type, whereas for the normal comparison subjects, the profile of “know” responses mirrored that of “remember” responses.

Conscious recollection paralleled the pattern of “remember” responses. There was a significant effect of group (F=53.5, df=1, 46, p<0.0001), with conscious recollection being lower in the patients than in the comparison subjects. There was a significant effect of word type (F=27.8, df=2, 92, p<0.0001) but no significant interaction between word type and group. Familiarity, as indexed by Fd′, showed a different pattern than did the “know” responses. There was a significant group effect (F=4.1, df=1, 46, p<0.05), with familiarity slightly lower in the patients than in the comparison subjects. Other statistical analyses did not result in significant findings.

Discussion

Our patients evaluated the emotional valence of words in a manner similar to that of the normal comparison subjects. Under these conditions, the patients, like the comparison subjects, consciously recollected emotional words better than neutral words. Despite lower recollection levels, their “remember” responses were more frequent for emotional than for neutral words and for positive than for negative words, with parallel variations in conscious recollection. In contrast, the levels of “know” responses and familiarity were not influenced by the emotional words. Similar profiles were observed in the normal comparison subjects, with the exception of the “know” responses, which showed significant variations: “know” and “remember” responses traded off against one another, probably because of a ceiling effect in overall recognition performance. The assumption that “remember” and “know” responses are exclusive, whereas conscious recollection and familiarity are independent, explains why normal comparison subjects exhibited different profiles of “know” responses and familiarity. The impact of emotional words on conscious recollection may be preserved because the evaluation of the emotional valence of words can occur automatically or with minimal strategic processes (5). Whether this impact is preserved with all types of emotional stimuli remains to be established.

Emotions are closely related to adaptive behavior at an automated level. But because emotions enhance conscious recollection, they also offer the flexibility of response based on memory for emotional events from the subject’s personal past. Evidence of a preserved effect of emotional stimuli on conscious recollection therefore suggests that patients may still benefit from such flexibility, at least in some situations. Other clinical implications may be more negative. Since emotion is the consequence of how people construe situations, some neutral events or experiences may become emotional by virtue of false beliefs or delusions. Because these events are more easily recalled later and, hence, more richly and vividly experienced in memory, they could contribute to the persistence and/or the enrichment of delusional experiences.

|

Received July 25, 2002; revision received Feb. 14, 2003; accepted March 6, 2003. From INSERM Unité 405, Département de Psychiatrie, Hôpitaux Universitaires. Address reprint requests to Dr. Danion, INSERM Unité 405, Département de Psychiatrie, Hôpitaux Universitaires, 1 place de l’Hôpital, BP 426, 67091 Strasbourg Cedex, France; [email protected] (e-mail).

1. Tulving E: Memory and consciousness. Can Psychol 1985; 26:1–12Crossref, Google Scholar

2. Ochsner KN: Are affective events richly recollected or simply familiar? The experience and process of recognizing feelings past. J Exp Psychol Gen 2000; 2:242–261Crossref, Google Scholar

3. Huron C, Danion J-M, Giacomoni F, Grangé D, Robert P, Rizzo L: Impairment of recognition memory with, but not without, conscious recollection in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:1737–1742Link, Google Scholar

4. Taylor SF, Liberzon I: Paying attention to emotion in schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry 1999; 174:6–8Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Yonelinas AP, Kroll NEA, Dobbins I, Lazzara M, Knight RT: Recollection and familiarity deficits in amnesia: convergence of remember-know, process dissociation, and receiver operating characteristic data. Neuropsychology 1998; 12:323–339Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Koh SD, Szoc R, Peterson RA: Short-term memory scanning in schizophrenic young adults. J Abnorm Psychol 1977; 5:451–460Crossref, Google Scholar

7. Andreasen NC: Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS). Iowa City, University of Iowa, 1984Google Scholar

8. Andreasen NC: Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS). Iowa City, University of Iowa, 1983Google Scholar