Impairment of Olfactory Identification Ability in Individuals at Ultra-High Risk for Psychosis Who Later Develop Schizophrenia

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Previous investigation has revealed stable olfactory identification deficits in neuroleptic-naive patients experiencing a first episode of psychosis, but it is unknown if these deficits predate illness onset. METHOD: The olfactory identification ability of 81 patients at ultra-high risk for psychosis was examined in relation to that of 31 healthy comparison subjects. Twenty-two of the ultra-high-risk patients (27.2%) later became psychotic, and 12 of these were diagnosed with a schizophrenia spectrum disorder. RESULTS: There was a significant impairment in olfactory identification ability in the ultra-high-risk group that later developed a schizophrenia spectrum disorder but not in any other group. CONCLUSIONS: These findings suggest that impairment of olfactory identification is a premorbid marker of transition to schizophrenia, but it is not predictive of psychotic illness more generally.

The ability of olfactory identification, a behavioral probe of circuitry involving the orbital frontal cortex, is consistently impaired in patients with chronic schizophrenia (1) and first episodes of psychosis (2–5); these impairments have been associated with negative symptoms (1, 2). In a recent longitudinal study of predominantly neuroleptic-naive first-episode patients with psychosis (2), olfactory identification deficits were apparent at baseline testing within a few days of commencement of treatment, were stable over a 6-month period, and did not distinguish those with schizophrenia or schizophreniform psychosis from those with other psychotic disorders. In addition, this study showed that olfactory identification deficits could not be attributed to the effects of cigarette smoking or cannabis use, both of which have been reported as high in younger groups with psychosis (2, 6). The results of these studies suggest that olfactory identification deficits are illness related, are apparent at illness onset, and are unlikely to be explained by the effects of medication. In addition, two studies have demonstrated similar (although less severe) olfactory impairments in the relatives of psychotic patients (7, 8), which suggests a genetic basis for the deficit. However, to date, there have been few studies investigating olfactory identification impairments in individuals at high risk for the development of psychosis. While previous studies of high-risk groups (9–11) have been limited by reliance on genetic vulnerability, a long follow-up period (25–30 years), high rates of attrition, and low levels of transition to psychosis, we have adopted an alternative strategy (12) that identifies people putatively at high risk of developing psychosis through a combination of trait and state risk factors (13). Its advantage is in finding a much higher rate of transition to psychosis than family history alone, and it does so within a relatively short follow-up period (41% rate of transition to psychosis within a 12-month period) (14). It has therefore been labeled an ultra-high-risk identification strategy to distinguish it from the traditional high-risk strategy of using family history alone.

In the current study, we examined olfactory identification ability in ultra-high-risk subjects in relation to healthy comparison subjects and compared the ultra-high-risk individuals who became psychotic with those who did not develop psychosis. Consistent with findings regarding first-episode psychosis, we predicted that olfactory identification deficits would be apparent in individuals who developed psychosis, but we did not expect to find differences among specific diagnoses of psychosis.

Method

Subjects

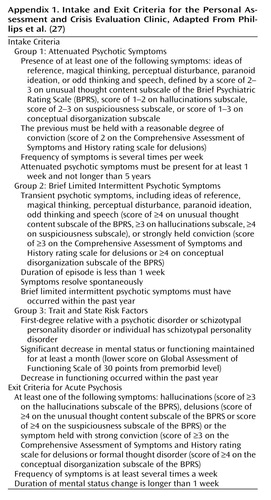

Subjects were recruited between April 1995 and August 1998 and consisted of two groups. The 31 healthy comparison subjects were similar in age and gender, and were recruited from a local technological college, from ancillary staff and their families, or by advertisements in local newspapers. The ultra-high-risk subjects (N=81) (56.7% male) were consecutively admitted to a personal assessment and crisis evaluation clinic. Detailed criteria for the identification of the ultra-high-risk group are described elsewhere (13) and are summarized in Appendix 1. The proportions of ultra-high-risk subjects in each intake group were as follows: attenuated symptoms, 48.1%; brief limited intermittent psychotic symptoms, 11.1%; trait and state symptoms, 13.6%; attenuated and brief limited intermittent psychotic symptoms, 1.2%; attenuated and trait and state symptoms, 11.1%; brief limited intermittent psychotic symptoms and trait and state symptoms, 12.3%; and all three groups of symptoms, 2.5%. In addition to these inclusion criteria, all ultra-high-risk patients were ages 14 to 30 years and had not experienced a previous psychotic episode (treated or untreated). During the 18-month period of the current investigation, 22 (27.2%) of the individuals became psychotic; 59 did not. Twelve (54.5%) of the ultra-high risk patients who became psychotic received a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizophreniform psychosis, while the remaining 10 were diagnosed with either major depression with psychotic features (N=2), schizoaffective disorder, depressed type (N=1), bipolar disorder (N=3), psychotic disorder not otherwise specified (N=3), or substance-induced psychotic disorder (N=1).

The subjects were required to have an adequate command of English. Subjects were excluded from the study based on the following criteria:

| 1. | Documented organic brain impairment | ||||

| 2. | History of head injury with loss of consciousness | ||||

| 3. | Current viral or other severe medical condition, upper respiratory tract disease, cold, sinus problem, or hay fever | ||||

| 4. | A history of nasal trauma | ||||

| 5. | Estimated premorbid IQ of less than 70 | ||||

| 6. | Documented poor eyesight or hearing | ||||

| 7. | The comparison subjects were excluded from study participation if they had a personal or documented family history of psychiatric illness in first- or second-degree relatives. | ||||

Measures

All subjects were assessed for olfaction and cognition with the following. Olfactory identification ability was measured with the University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test (15), a standardized, self-administered multiple-choice scratch-and-sniff test consisting of four booklets, each containing 10 items. This test has been normatively adjusted for Australian samples (16). Estimated premorbid IQ was assessed with the Australian-adjusted version of the National Adult Reading Test (17). Norms were adjusted for years of education. Details of smoking history were also obtained. Diagnosis of psychopathology and ratings of the ultra-high-risk subjects were made with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (18), the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) (19), and the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS) (20).

Procedure

All subjects provided written informed consent, including parental consent for those less than 18 years of age, in accordance with guidelines provided by the local mental health service research and ethics committees and the departments of psychiatry and psychology of the University of Melbourne.

Results

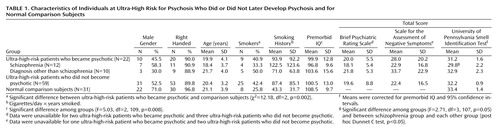

Table 1 lists the baseline demographic, smoking, clinical, cognitive, and olfactory characteristics of the ultra-high-risk and comparison groups. The ultra-high-risk patients who did or did not became psychotic differed from the comparison subjects regarding only National Adult Reading Test estimated premorbid IQ (analysis of variance) and the proportion of subjects who smoked.

There were no significant differences in ability on the smell identification test between the ultra-high-risk subgroups (psychotic and nonpsychotic) and the comparison subjects, after control was added for premorbid IQ (F=2.05, df=2, 108, p=0.133, analysis of covariance [ANCOVA]). However, when the ultra-high-risk group that later became psychotic was divided on the basis of their psychotic diagnosis (ultra-high-risk patients who were diagnosed as having schizophrenia or psychoses other than schizophrenia), an ANCOVA with control for premorbid IQ revealed a significantly lower ability on the smell identification test in the ultra-high-risk patients who later became psychotic (ANCOVA). Post hoc comparisons revealed that the ultra-high-risk patients who later became psychotic had significantly poorer olfaction ability than all other groups.

Individual correlations for the groups between scores on the University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test and other variables were examined, with covariance for premorbid IQ. For the ultra-high-risk subjects who did not become psychotic, a significant association was found between scores on the smell identification test and age, indicating that older subjects had better olfactory identification ability. Data were as follows: ultra-high-risk subjects who did not become psychotic: r=0.37, p=0.005; ultra-high-risk subjects who were diagnosed as having schizophrenia: r=0.03, p=0.94; ultra-high-risk patients who were diagnosed as having psychoses other than schizophrenia: r=0.05, p=0.89; and healthy comparison subjects: r=–0.29, p=0.12. No significant associations were found between global SANS or BPRS scores and olfaction identification ability in any ultra-high-risk group and, for smokers, between pack-years smoked and olfaction identification ability in any group.

To examine further the effects of cigarette smoking on performance on the smell identification test, the patient and comparison groups were divided into smokers and nonsmokers. Smoking had no effect on smell identification ability across the groups (F=0.14, df=2, 45, p=0.71), and no interaction between study group and smoking was found (F=2.76, df=1, 45, p=0.10). Overall, those who smoked had virtually identical mean scores on the smell identification test as the nonsmokers (smokers: mean=32.4, SD=1.1; nonsmokers: mean=32.2, SD=1.2).

Sex differences have previously been found in performance on the smell identification test, such that olfaction ability in the male sex is generally more compromised than in the female sex (21). A subanalysis of our data (ultra-high-risk patients who became psychotic versus those who did not versus comparison subjects) supported these findings (F=16.8, df=1, 105, p<0.001). However, there was no interaction effect (F=1.0, df=2, 105, p=0.37). Of interest, the group effect did approach a sigificant level (F=3.0, df=2, 105, p=0.053). An analysis comparing subgroups of the ultra-high-risk group that became psychotic based on their outcome diagnosis produced similar findings (sex effect: F=10.5, df=1, 103, p=0.002; group effect: F=2.3, df=3, 103, p=0.09; interaction: F=1.2, df=3, 103, p=0.33).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine olfactory identification ability in a group of individuals at ultra-high risk of developing psychosis. Relative to a healthy comparison group, there was significantly lower olfactory identification ability, specifically in the patients who developed schizophrenia or schizophreniform psychosis. Indeed, these subjects also performed significantly worse than all other ultra-high-risk groups. However, there was no evidence of lower olfactory identification ability in patients who later developed other psychotic disorders.

Smoking history did not significantly affect olfaction identification ability, which is consistent with our findings in a group with first-episode psychosis (2). However, unlike the results from that same first-episode cohort, there was no association between olfaction ability on University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test and the age of the ultra-high-risk group that later became psychotic. In contrast, age was associated with olfactory ability in the ultra-high-risk group that did not become psychotic. The latter is consistent with published norms (16), demonstrating that improvement in olfaction ability occurs through early childhood into mid-adolescence in normal populations, although no association was found in our relatively small comparison group. Furthermore, we failed to find a relationship between olfactory ability and negative symptoms, as was previously shown in patients with established illness (1, 2).

In contrast with our predictions and with data in patients with established psychosis (1, 2, 5), olfactory identification deficits were found only in subjects who later developed schizophrenia and not in those who later developed other psychotic disorders. One possible explanation for this lack of association is that the onset of schizophrenia leads to an arrest of normal development in olfactory ability, such that ultra-high-risk patients who later become psychotic do not make the normal gains seen in ultra-high-risk patients who were diagnosed as having psychoses other than schizophrenia and those who did not become psychotic. More specifically, we suggest that the incipient onset of schizophrenia compromises normal frontal lobe development and therefore interferes with the development of neuropsychological functions mediated by these regions. Our previous neuroimaging (22) and neuropsychological (23) data support such a view. In addition, given our previous finding that first-episode patients with psychotic disorders other than schizophrenia also have impaired olfactory identification ability, this may suggest a decline in performance during the transition to frank psychosis in this group. A decline in olfactory identification might be associated with changes involving the orbital frontal cortex, which has been reported to occur over the transition period (22). Although these two explanations are not mutually exclusive (and therefore additional impairments may arise in ultra-high-risk patients who are diagnosed with schizophrenia as they become psychotic), longitudinal data are required to examine the effect of developmental stage at illness onset and the impact of further brain changes with illness progression.

Our subanalysis by gender revealed overall that olfactory identification ability in men was more compromised in test performance than that of the women, although the interaction effect was not significant. Nonetheless, an inspection of the mean scores broken down by gender did reveal that the most impaired performance was seen in the men who later developed schizophrenia, suggesting that our failure to discern an interaction of group by sex was because of the small numbers in each group. Our previous work in neuroleptic-naive patients with first-episode psychosis also found no group-by-gender interaction (2), although that analysis did not distinguish between diagnostic subgroups. Clearly, further investigation of the relationship between diagnosis and gender is required in this population.

A number of issues regarding methods must be considered in the interpretation of the findings of this study. The ultra-high-risk group that later developed psychosis may not be representative of all patients with psychosis, although follow-up studies of the same group suggest that they do not differ from patients with a first episode of psychosis in terms of psychopathology (24). Furthermore, the genetic, behavioral, and functional difficulties that bring high-risk individuals to the attention of our clinic could be a result of some generalized vulnerability that includes a greater risk for psychosis. Ideally, these individuals should be assessed before presentation, that is, before they come in for treatment in vulnerable mental states. However, such prevention strategies are difficult to achieve and require long-term follow-up studies, such as in work by the Edinburgh group (25). Finally, the diagnosis of schizophreniform or affective psychosis can change over time (26), meaning that further studies examining the diagnostic specificity of olfactory deficits in larger high-risk groups are needed.

|

Received Sept. 24, 2002; revision received Feb. 5, 2003; accepted March 14, 2003. From the Department of Psychiatry and the Department of Psychology, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia; the Mental Health Research Institute, Applied Schizophrenia Division, Parkville, Victoria, Australia; the Youth Program, Personal Assessment and Crisis Evaluation Clinic, ORYGEN Youth Health; and the Cognitive Neuropsychiatry Research and Academic Unit, Sunshine Hospital, St. Albans, Victoria, Australia. Address reprint requests to Dr. Brewer, ORYGEN Youth Health, Locked Bag 10, Parkville, Victoria 3052, Australia; [email protected] (e-mail). Funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council, Schizophrenia Research Unit; funded in part by Janssen-Cilag, Novartis, and Myer Melbourne. The authors thank Paul Dudgeon for statistical consultation.

|

Appendix 1.

1. Brewer WJ, Edwards J, Anderson V, Robinson T, Pantelis C: Neuropsychological, olfactory, and hygiene deficits in men with negative symptom schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry 1996; 40:1021–1031Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Brewer WJ, Pantelis C, Anderson V, Velakoulis D, Singh B, Copolov DL, McGorry PD: Stability of olfactory identification deficits in neuroleptic-naive patients with first-episode psychosis. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:107–115Link, Google Scholar

3. Moberg PJ, Doty RL, Turetsky BI, Arnold SE, Mahr RN, Gur RC, Bilker W, Gur RE: Olfactory identification deficits in schizophrenia: correlation with duration of illness. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:1016–1018Link, Google Scholar

4. Seidman LJ, Goldstein JM, Goodman JM, Koren D, Turner WM, Faraone SV, Tsuang MT: Sex differences in olfactory identification and Wisconsin card sorting performance in schizophrenia: relationship to attention and verbal ability. Biol Psychiatry 1997; 42:104–115Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Kopala LC, Clark C, Hurwitz T: Olfactory deficits in neuroleptic naive patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 1992; 8:245–250Crossref, Google Scholar

6. Goff DC, Henderson DC, Amico E: Cigarette smoking in schizophrenia: relationship to psychopathology and medication side effects. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:1189–1194Link, Google Scholar

7. Kopala LC, Good KP, Torrey EF, Honer WG: Olfactory function in monozygotic twins discordant for schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:134–136Link, Google Scholar

8. Kopala LC, Good KP, Morrison K, Bassett AS, Alda M, Honer WG: Impaired olfactory identification in relatives of patients with familial schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:1286–1290Link, Google Scholar

9. Cornblatt BA, Keilp JG: Impaired attention, genetics, and the pathophysiology of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1994; 20:31–46Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Nuechterlein KH, Dawson ME, Green MF: Information-processing abnormalities as neuropsychological vulnerability indicators for schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 1994; 384:71–79Medline, Google Scholar

11. Hodges A, Byrne M, Grant E, Johnstone EC: People at risk of schizophrenia: sample characteristics of the first 100 cases in the Edinburgh High-Risk Study. Br J Psychiatry 1999; 174:547–553Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Bell R: Multiple-risk cohorts and segmenting risk as solutions to the problem of false positives in risk for the major psychoses. Psychiatry 1992; 55:370–381Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Yung AR, McGorry PD: The prodromal phase of first-episode psychosis: past and current conceptualizations. Schizophr Bull 1996; 22:353–370Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Yung AR, Phillips LJ, McGorry PD, McFarlane CA, Francey S, Harrigan S, Patton GC, Jackson HJ: Prediction of psychosis: a step towards indicated prevention of schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry 1998; 172(suppl 33):14–20Google Scholar

15. Doty RL, Shaman P, Dann M: Development of the University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test: a standardized microencapsulated test of olfactory function. Physiol Behav 1984; 32:489–502Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Mackay-Sim A, Doty RL: The University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test: normative adjustment for Australian subjects. Australian J Otolaryngology 2001; 4:174–177Google Scholar

17. Willshire D, Kinsella G, Prior M: Estimating WAIS-R IQ from the National Adult Reading Test: a cross-validation. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 1991; 13:204–216Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MB: The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID), I: history, rationale, and description. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49:624–629Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. McGorry PD, Goodwin R, Stuart G: The development, use and reliability of the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (Nursing Modification): an assessment procedure for the nursing teams in clinical and research settings. Compr Psychiatry 1988; 29:575–587Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Andreasen NC: Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS). Iowa City, University of Iowa, 1983Google Scholar

21. Kopala L, Clark C: Implications of olfactory agnosia for understanding sex differences in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1990; 16:255–260Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Pantelis C, Velakoulis D, McGorry PD, Wood SJ, Suckling J, Phillips LJ, Yung AR, Bullmore ET, Brewer W, Soulsby B, Desmond P, McGuire PK: Neuroanatomical abnormalities before and after onset of psychosis: a cross-sectional and longitudinal MRI comparison. Lancet 2003; 361:281–288Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Pantelis C, Yücel M, Wood SJ, McGorry PD, Velakoulis D: Early and late neurodevelopmental disturbances in schizophrenia and their functional consequences. Aust NZ J Psychiatry 2003, 37:399–406Google Scholar

24. Yung AR, McGorry PD, McFarlane CA, Jackson HJ, Patton GC, Rakkar A: Monitoring and care of young people at incipient risk of psychosis. Schizophr Bull 1996; 22:283–303Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Johnstone EC, Abukmeil SS, Byrne M, Clafferty R, Grant E, Hodges A, Lawrie SM, Owens DG: Edinburgh High Risk Study—findings after four years: demographic, attainment and psychopathological issues. Schizophr Res 2000; 46:1–15Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Fennig S, Kovasznay B, Rich C, Ram R, Pato C, Miller A, Rubinstein J, Carlson G, Schwartz JE, Phelan J: Six-month stability of psychiatric diagnoses in first-admission patients with psychosis. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:1200–1208Link, Google Scholar

27. Phillips LJ, Velakoulis D, Pantelis C, Wood S, Yuen HP, Yung AR, Desmond P, Brewer W, McGorry PD: Non-reduction in hippocampal volume is associated with higher risk of psychosis. Schizophr Res 2002; 58:145–158Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar