Dissociation, Childhood Trauma, and Ataque De NerviosAmong Puerto Rican Psychiatric Outpatients

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study examined the relationships of dissociation and childhood trauma with ataque de nervios. METHOD: Forty Puerto Rican psychiatric outpatients were evaluated for frequency of ataque de nervios, dissociative symptoms, exposure to trauma, and mood and anxiety psychopathology. Blind conditions were maintained across assessments. Data for 29 female patients were analyzed. RESULTS: Among these 29 patients, clinician-rated dissociative symptoms increased with frequency of ataque de nervios. Dissociative Experiences Scale scores and diagnoses of panic disorder and dissociative disorders were also associated with ataque frequency, before corrections were made for multiple comparisons. The rate of childhood trauma was uniformly high among the patients and showed no relationship to dissociative symptoms and disorder or number of ataques. CONCLUSIONS: Frequent ataques de nervios may, in part, be a marker for psychiatric disorders characterized by dissociative symptoms. Childhood trauma per se did not account for ataque status in this group of female outpatients.

Ataque de nervios (“attack of nerves”) is a culturally defined Latino syndrome usually triggered by acute stress and typically characterized by paroxysms of uncontrollable shouting and crying, trembling, palpitations, and aggressiveness (1, 2). Although it has a prevalence of 13.8% in Puerto Rico and is considered normal by many Latinos, ataque is often associated with mood and anxiety disorders (1). Case reports suggesting that dissociative symptoms are a primary feature of ataque have never been investigated systematically. These symptoms include depersonalization, amnesia, identity alteration, and trance-like states (2). In addition, although ataque has been linked to childhood trauma (3), the relationship between exposure to trauma and dissociation among ataque sufferers has not been explored.

This pilot study examined the relationship of ataque status to dissociation and childhood trauma to help clarify whether ataque de nervios can be understood as a culturally patterned dissociative reaction to stress arising in subjects predisposed by childhood exposure to trauma.

Method

Forty adult Puerto Rican psychiatric outpatients were included in the study. Patients with psychotic, organic, or current substance abuse disorders were excluded.

Lifetime number of ataques de nervios was assessed by using the clinician-rated Explanatory Model Interview Catalogue (4), which elicits key elements of cultural syndromes. Subjects were coded positive if their self-labeled ataque de nervios corresponded to the description in the DSM-IV Glossary of Culture-Bound Syndromes. Five ambiguous codings were reviewed along with five unambiguous codings by blinded independent experts. All unambiguous codings were confirmed. Three out of the five ambiguous cases of ataque were excluded from the data analysis because of idiosyncratic self-labelings inconsistent with typical usage (e.g., “depression attacks”).

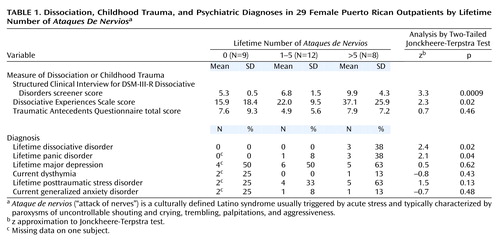

Of the remaining 37 subjects, ataque was coded absent (N=14), present and quantifiable (N=16) (the mean number of ataques was 4.7 [range=1–15]), or present with extreme frequency (N=7) (number of ataques was “too many to count”). By dividing subjects with ataques at the median number of five ataques, three groups were created for statistical comparisons (Table 1). Because only eight men were included in the study, data are presented only for the female patients (N=29).

Psychiatric diagnoses for the mood and anxiety disorders associated with ataque(1) were determined by using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID). Diagnoses of dissociative disorders were determined by using the clinician-rated screening questionnaire of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R Dissociative Disorders (SCID-D) (5), which generates severity scores for five dissociative symptom dimensions and the probability of a categorical diagnosis. Only cases with definite probability were included. Subjects also completed the self-report Dissociative Experiences Scale (6).

Exposure to trauma before age 18 was ascertained with the clinician-rated Traumatic Antecedents Questionnaire (7), which provides the sum of eight trauma categories across three developmental stages. A ninth category of “deaths of offspring and child siblings” was added on the basis of clinical experience. According to standard Traumatic Antecedents Questionnaire practice, culturally accepted corporal punishment and uniform household poverty were coded negative, and recurrent abuse by one perpetrator was coded as a single trauma in each developmental stage.

Blind conditions were maintained across all instruments, except between the two SCID interviews. Instruments were administered in Spanish and translated following standard translation methods. After complete description of the study to the subjects, written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Two-tailed Jonckheere-Terpstra tests (8) were used to analyze the hypothesized ordered relationship between the outcome variables and ataque frequency. This test assesses whether the order of the responses relative to the order of the number of ataques appears random. Demographic variables were analyzed by using analysis of variance.

Results

Linear regression identified a significant interaction between gender and ataque frequency with respect to SCID-D scores (F=7.7, df=1, 31, p=0.009) and Dissociative Experiences Scale scores (F=6.3, df=1, 31, p=0.02), requiring separate analysis by gender. As already noted, data are presented only for the 29 female patients.

All of the women had come from Puerto Rico. Nine had not experienced ataque, 12 had experienced one to five ataques, and eight had experienced more than five ataques. No significant differences were found between the groups in age (mean=47.5, SD=7.8), years of education (mean=7.8, SD=4.9), or age at migration (mean=25.8, SD=10.6).

Dissociative Experiences Scale and SCID-D scores as well as rates of lifetime dissociative disorder and panic disorder showed a significant positive association with number of ataques (Table 1). All three women with dissociative disorder had dissociative disorder not otherwise specified.

Traumatic Antecedents Questionnaire total score (Table 1) and scores for each independent trauma subcategory (data not shown) were not significantly associated with ataque frequency. Exclusion of the added category for child deaths did not affect the analysis.

After Bonferroni correction for nine comparisons in Table 1, only the SCID-D scores showed a significant association with ataque frequency.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first empirical evidence demonstrating a specific relationship between ataque de nervios and dissociation (2). Even after correcting for multiple comparisons, clinician-rated dissociative symptoms increased significantly with lifetime ataque frequency among female Puerto Rican psychiatric outpatients. The fact that the group without ataques also had mood and anxiety psychopathology suggests that this finding is not solely attributable to the association between general psychopathology and dissociation (9). The very elevated Dissociative Experiences Scale mean score for the group with more than five ataques (score=37.1) is similar to scores for patients with dissociative disorder not otherwise specified (score=35.3) (10), validating our finding of a high rate of dissociative disorder not otherwise specified.

In Puerto Rico, ataque is twice as prevalent among women as men (1). Our finding of a gender interaction between dissociative symptoms and ataque frequency is the first suggestion to our knowledge of a gender difference in ataque phenomenology. Future research should explore whether this gender interaction signals a sex-specific relationship between dissociation and ataque.

Contrary to our hypothesis, childhood trauma was not associated with ataque frequency or dissociation. Rather, exposure to trauma was uniformly high across groups (7), suggesting that, in this group of patients, factors in addition to childhood trauma account for ataque status. This contradicts previous findings with a different clinical population and trauma scale that showed an association between ataque and childhood trauma (3) but is consistent with a multifactorial model of dissociation and ataque(10). Exposure to trauma was not sufficient to cause frequent ataques, but whether it was necessary remains unclear.

Before Bonferroni correction, ataque frequency was associated with panic and dissociative disorders among female patients. This confirms the overlap between ataque and panic and also validates the concept that ataque is a more inclusive construct diagnostically (1). In addition, the very high rate of posttraumatic stress disorder among patients with frequent ataques, although statistically nonsignificant, should be investigated in larger samples. Taken together, these findings suggest that frequent ataques are, in part, a marker for psychiatric disorders characterized by dissociative symptoms.

There is no research at present that might inform treatment of this common Latino syndrome. Our study suggests that techniques addressing pathological dissociation might be useful. Future research should continue to investigate the relationship between trauma and dissociation, including cultural factors that might predispose to syndromes such as frequent ataques de nervios.

|

Received May 15, 2001; revision received Aug. 13, 2001; accepted March 19, 2002. From the Anxiety Disorders Clinic, New York State Psychiatric Institute; the Department of Psychiatry, Columbia University, New York; and the Department of Social Medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston. Address reprint requests to Dr. Lewis-Fernández, Anxiety Disorders Clinic, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Unit 69, 1051 Riverside Dr., New York, NY 10032; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by a Harvard Medical School Dupont-Warren Research Fellowship in Psychiatry, the Nathan Cummings Foundation, the MacArthur Foundation Mind-Body Network, and NIMH grants MH-18006 (Fellowship Program in Medical Anthropology) and MH-55165 (Underrepresented Minority Research Supplement, Dr. Lewis-Fernández). The authors thank Peter Guarnaccia, Randall Marshall, J. Christopher Perry, Arthur Kleinman, Byron and MaryJo Good, Mitchell Weiss, David Spiegel, Glorisa Canino, Vivian Febo, Rafael Ramírez, Ana Ortiz, Andrew Schmidt, Deborah Goetz, Pedro Ruiz, Carlos Blanco, and Michael Liebowitz.

1. Guarnaccia PJ, Canino G, Rubio-Stipec M, Bravo M: The prevalence of ataques de nervios in the Puerto Rico Disaster Study. J Nerv Ment Dis 1993; 181:157-165Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Lewis-Fernández R: Culture and dissociation: a comparison of ataque de nervios among Puerto Ricans and possession syndrome in India, in Dissociation: Culture, Mind, and Body. Edited by Spiegel D. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1994, pp 123-167Google Scholar

3. Schechter DS, Marshall R, Salmán E, Goetz D, Davies S, Liebowitz MR: Ataque de nervios and history of childhood trauma. J Trauma Stress 2000; 13:529-534Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Weiss M: Explanatory Model Interview Catalogue (EMIC). Transcultural Psychiatry 1997; 34:235-263Crossref, Google Scholar

5. Steinberg M, Rounsaville B, Cicchetti DV: The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R Dissociative Disorders: preliminary report on a new diagnostic instrument. Am J Psychiatry 1990; 147:76-82Link, Google Scholar

6. Bernstein EM, Putnam FW: Development, reliability, and validity of a dissociation scale. J Nerv Ment Dis 1986; 174:727-735Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Herman JL, Perry JC, van der Kolk BA: Childhood trauma in borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1989; 146:490-495Link, Google Scholar

8. Hollander M, Wolfe DA: Nonparametric Statistical Methods. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1972Google Scholar

9. Mulder RT, Beautrais AL, Joyce PR, Fergusson DM: Relationship between dissociation, childhood sexual abuse, childhood physical abuse, and mental illness in a general population sample. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:806-811Abstract, Google Scholar

10. Van Ijzendoorn MH, Schuengel C: The measurement of dissociation in normal and clinical populations. Clin Psychol Rev 1996; 16:365-382Crossref, Google Scholar