Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study of Risperidone for the Treatment of Disruptive Behaviors in Children With Subaverage Intelligence

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The short-term efficacy and safety of risperidone in the treatment of disruptive behaviors was examined in a well-characterized cohort of children with subaverage intelligence. METHOD: In this 6-week, multicenter, double-blind, parallel-group study of 118 children (aged 5–12 years) with severely disruptive behaviors and subaverage intelligence (IQ between 36 and 84, inclusive), the subjects received 0.02–0.06 mg/kg per day of risperidone oral solution or placebo. The a priori primary efficacy measure was the change in score from baseline to endpoint on the conduct problem subscale of the Nisonger Child Behavior Rating Form. RESULTS: The risperidone group showed significantly greater improvement than did the placebo group on the conduct problem subscale of the Nisonger Child Behavior Rating Form from week 1 through endpoint (change in score of –15.2 and –6.2, respectively). Risperidone was also associated with significantly greater improvement than placebo on all other Nisonger Child Behavior Rating Form subscales at endpoint, as well as on the Aberrant Behavior Checklist subscales for irritability, lethargy/social withdrawal, and hyperactivity; the Behavior Problems Inventory aggressive/destructive behavior subscale; a visual analogue scale of the most troublesome symptom; and the Clinical Global Impression change score. The most common adverse effects reported during risperidone treatment were headache and somnolence. The extrapyramidal symptom profile of risperidone was comparable to that of placebo. Mean weight increases of 2.2 kg. and 0.9 kg occurred in the risperidone and placebo groups, respectively. CONCLUSIONS: Risperidone was effective and well tolerated for the treatment of severely disruptive behaviors in children with subaverage IQ.

Disruptive behavior disorders are the most common psychiatric disorders of childhood, occurring in 4%–9% of the pediatric population (1, 2). The prevalence of conduct disorder as well as of other disruptive behavior disorders (e.g., oppositional defiant disorder, disruptive behavior disorder not otherwise specified) is particularly high among children with a below-average IQ (2–9). One study reported that behavioral disturbances were three to four times more common in children with intellectual limitations than in comparison children of the same age (4).

Disruptive behavior disorders are associated with sequelae that may result in serious consequences for both the child and society, including legal trouble, school suspension, substance abuse, and physical injury (2, 10). Many children with intellectual limitations and severe behavior disorders require out-of-home placement (4). The costs of caring for individuals with disruptive behavior disorders, which may include loss of productivity and costs of health care, housing, law enforcement, and security, as well as victim and family costs, are substantial (11). In 1989, the cost of caring for intellectually disabled persons who exhibited destructive behavior was approximately $3 billion (4).

A variety of treatments have been considered for patients with disruptive behavior disorders. Nonpharmacologic approaches include behavior modification, psychotherapy, and cognitive and social interventions and are the subject of ongoing trials evaluating short- and long-term effectiveness. Pharmacologic approaches to disruptive behaviors include the use of mood stabilizers and antipsychotic agents (1, 3, 6, 9, 10, 12, 13). Although antipsychotics are often used in the treatment of severe disruptive behavior disorders, few controlled studies have examined the use of these treatments for this purpose. Furthermore, many studies are limited by the small size of the study group, short duration, and open-label and noncomparative design. The data on treatment of behavior disorders in patients with intellectual limitations are even fewer. One review of treatment with classic antipsychotics in subjects with mental retardation noted reductions in aggression in 11 studies and no effect or worsening of aggression in four studies (14). However, the experimental procedures were considered methodologically sound in only three (20%) of these 15 studies.

Two double-blind, placebo-controlled trials (15, 16) and one open-label trial (17) of risperidone involving children with disruptive behavior disorders (total of 71 subjects) have been conducted. All three studies found that risperidone was associated with significantly greater reductions in aggressive behavior compared with placebo. Moreover, several open studies and case reports have described the successful use of risperidone to control severe behavior problems in a variety of diagnoses (18–42). To our knowledge, the study reported here is the first randomized, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of an atypical antipsychotic involving a relatively large number of pediatric patients with severely disruptive behaviors and mild or moderate intellectual disability or low-normal IQ.

Method

Patients

All enrolled children had a total rating ≥24 (i.e., the 70th percentile for a group of children attending a center for developmental disabilities) on the conduct problem subscale of the Nisonger Child Behavior Rating Form (43, 44). Other inclusion criteria were a DSM-IV axis I diagnosis of conduct disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, or disruptive behavior disorder not otherwise specified; an axis II diagnosis of subaverage IQ (IQ ≥36 and ≤84); and a Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scale (45) score ≤84. Individuals with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder were also eligible if they met all other inclusion criteria. Subjects were also required to be healthy and age 5 through 12 years and to have symptoms sufficiently severe that the investigator felt there was a need for antipsychotic treatment. A responsible person was required to be available to accompany the subject for study visits, to provide reliable assessments, and to dispense study medications.

Exclusion criteria included a diagnosis of pervasive developmental disorder, schizophrenia, or other psychotic disorder; head injury as a cause of intellectual disability; or a seizure disorder requiring medication. A known hypersensitivity to risperidone or neuroleptics, a history of tardive dyskinesia or neuroleptic malignant syndrome, serious or progressive illnesses, the presence of human immunodeficiency virus, and use of an investigational drug within the previous 30 days were also exclusion criteria. Subjects were excluded if they had received risperidone previously. Subjects with laboratory values outside the normal range were excluded unless the investigator determined that the deviations were not clinically relevant. Female subjects of childbearing age were excluded if they were sexually active and not using a medically validated birth control method.

Study Design

The trial was a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, 6-week, parallel-arm comparison of placebo and risperidone conducted at 11 centers. The institutional review board at each center approved the study. After the study was completely explained to each patient and his or her guardian or legal representative, the child (if capable) and the patient’s guardian or legal representative provided written informed consent.

The screening process included a medical history, physical and psychiatric examination, ECG, measurement of vital signs and weight, clinical laboratory assessments, and completion of the Nisonger Child Behavior Rating Form (43, 44), Aberrant Behavior Checklist (46), Behavior Problems Inventory (47), and Child Symptom Inventory (48) by the child’s parent. The Child Symptoms Inventory is a standardized informant scale used to assess all of the major DSM-IV conditions for children. After the parent rated the child with the Child Symptoms Inventory, the Nisonger Child Behavior Rating Form, and the Aberrant Behavior Checklist, the clinician conducted medical and psychiatric histories and completed a direct examination of the child. On the basis of this information, the clinician made a DSM-IV diagnosis. Child psychiatrists, pediatricians, and licensed clinical psychologists made the diagnoses.

In addition, the parent was interviewed with the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scale, and the child was assessed with an IQ test (Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scale or the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, 3rd. ed. [49]). After screening, all eligible subjects received single-blind treatment with placebo for 1 week to rule out placebo responders. Patients whose Nisonger Child Behavior Rating Form conduct problem subscale score was reduced to <24 in response to placebo were removed from the study. The remaining patients entered the 6-week, double-blind phase of the study and were randomly assigned to receive risperidone or placebo. At each study site, randomization was stratified by diagnosis (conduct disorder versus other diagnoses [oppositional defiant disorder or disruptive behavior disorder not otherwise specified]). An intent-to-treat design was used, with the last observation carried forward for any participants who did not complete the trial.

Medication

Risperidone solution was administered at a dose of 0.01 mg/kg per day on days 1 and 2 and was increased to 0.02 mg/kg per day on day 3. Thereafter, the dose was adjusted at weekly intervals as judged necessary by the clinician. Increases or decreases in the dose were made in increments of no more than 0.02 mg/kg per day. The maximum dose was 0.06 mg/kg per day. The entire dose was administered once daily in the morning unless the subject experienced breakthrough symptoms in the evening, in which case the regimen could be changed to twice daily. After day 28, the daily dose remained constant until the end of the study. The two study solutions were identical in appearance, taste, and smell. Study medication was provided by the Janssen Research Foundation.

Concomitant use of other antipsychotics, anticonvulsants, antidepressants, lithium, carbamazepine, valproic acid, or cholinesterase inhibitors was not permitted. Use of consistent doses of psychostimulants (e.g., methylphenidate, pemoline, dextroamphetamine) was permitted if the dose had been stable for at least 30 days before the start of the study. Behavioral therapy was permitted if it was initiated at least 30 days before the start of the study and if subjects still continued to meet the symptom severity criteria for trial inclusion despite the behavioral therapy. No changes to psychostimulant use or behavioral therapy were allowed during the trial. No medications for sleep or anxiety were to be initiated during the trial. Subjects receiving antihistamines, chloral hydrate, or melatonin for sleep before the screening visit could continue this medication unchanged during the trial. Medications commonly used to treat extrapyramidal symptoms (e.g., diphenhydramine, benztropine, trihexyphenidyl) were discontinued at study entry. If extrapyramidal symptoms arose during the study, the dose of study medication was decreased. If this resulted in deterioration of conduct disorder symptoms or failed to improve the extrapyramidal symptoms, antiextrapyramidal-symptom medication could be considered. All concomitant prescription and nonprescription medication use was recorded.

Efficacy and Safety Assessments

After screening, visits were scheduled on day 0 (initiation of double-blind treatment) and on days 7, 14, 21, 28, 35, and 42 (final visit).

The primary efficacy measure was the change from baseline to endpoint on the conduct problem subscale of the Nisonger Child Behavior Rating Form problem behaviors section. Most of the items on the conduct problem subscale correspond with a DSM-IV symptom for conduct disorder or other disruptive behavior disorders. Secondary efficacy measures included change in scores on other Nisonger Child Behavior Rating Form problem behaviors section subscales and on the social competence section subscales. Other secondary measures included the Aberrant Behavior Checklist subscale scores, the investigator’s rating on the Clinical Global Impression (CGI) severity scale, and CGI change scores. Also, change in a visual analogue scale rating of an individual target symptom for each patient (the symptom considered most disturbing for the patient and his/her surroundings) was evaluated.

Adverse events were recorded throughout the treatment period. Routine laboratory tests and measurements of prolactin and growth hormone were conducted. Measurements of leptin, triglyceride, and cholesterol were not obtained. Physical examinations and electrocardiograms were performed at screening and at the end of treatment. Measures of cognitive function included the Continuous Performance Test (50) and a modification of the California Verbal Learning Test, Children’s Version (51), and were performed at baseline and endpoint. Weekly safety assessments included a visual analogue scale rating of sedation, Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale scores for the severity of extrapyramidal symptoms (52), and measures of vital signs and weight.

Statistical Analyses

Determination of size of the study group was based on the assumption that a clinically relevant difference in mean change from baseline to endpoint between risperidone and placebo was at least 8 points (with SD=13) on the conduct problem subscale of the Nisonger Child Behavior Rating Form (43).

All randomly assigned subjects who took at least one dose of double-blind study medication and who had at least one postbaseline assessment were included in the efficacy analyses. All patients who received double-blind medication were included in the safety analysis. An analysis of covariance model (ANCOVA) was used to test between-group differences and included factors for subjects’ IQ, treatment, site, disorder stratum, and baseline score on the conduct problem subscale. A treatment-by-site interaction and the interaction of treatment with the baseline conduct problem subscale score were evaluated in separate ANCOVA models.

For the secondary efficacy variables (except CGI severity and change scores) and the visual analogue scale of sedation, the change from baseline was calculated at each visit and at endpoint. Each was analyzed by ANCOVA with factors for treatment, site, and baseline score. Treatment interactions were evaluated in a separate model. The CGI change score was compared between the treatment groups with the Van Elteren test (53). Use of the Van Elteren test, a nonparametric statistic, allowed for control of the effects of site and diagnosis (conduct disorder versus other disruptive behavior disorder) while testing for the effect of treatment. The Van Elteren test is identical to the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel row-mean test, using modified ridit scoring.

To investigate the effect of somnolence on efficacy, scores on the Nisonger Child Behavior Rating Form, the Behavior Problems Inventory, the Aberrant Behavior Checklist, and the visual analogue scale of sedation were analyzed for the subgroup of subjects who did not experience somnolence (reported as an adverse event) during the double-blind period.

Between-group comparisons of Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale scores were analyzed with a Van Elteren test that controlled for site and diagnosis. For vital signs, ECG, and body weight, within-treatment-group comparisons were assessed with the paired t test. Between-group comparisons were performed by using analysis of variance (ANOVA) with factors for treatment, site, and disorder stratum. For patients who dropped out, last observations were carried forward to all subsequent weeks.

Results

Subjects

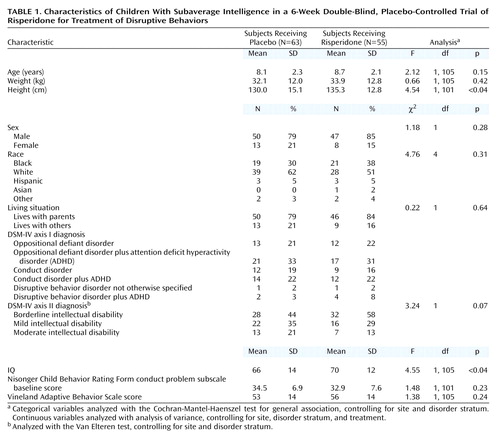

A total of 142 subjects were screened for the study, and 119 were randomly assigned to treatment groups (23 subjects did not meet screening criteria). A total of 118 subjects received double-blind study medication; 55 received risperidone and 63 received placebo. However, no efficacy data were recorded for three patients in the risperidone group, and hence they were not included in any efficacy analyses. Demographic and clinical characteristics of the two groups were comparable at baseline (Table 1), except that the risperidone group was slightly taller and had a slightly higher IQ than did the placebo group. Because of the difference in IQ, the statistical model used to analyze the results controlled for IQ.

Forty-three patients (78%) in the risperidone group and 44 (70%) in the placebo group completed the study. Twelve risperidone patients and 19 placebo patients withdrew prematurely. The reasons were as follows: 1) insufficient response (four patients [7.3%] in the risperidone group and 15 [23.8%] in the placebo group), 2) noncompliance (three [5.5%] in the risperidone group), 3) adverse event (two [3.6%] in the risperidone group), 4) lost to follow-up (three [4.8%] in the placebo group and one [1.8%] in the risperidone group), 5) consent withdrawn (one [1.6%] in the placebo group, and one [1.8%] in the risperidone group), and 6) medication lost (one [1.8%] in the risperidone group).

Exposure to Study Medication

The mean dose of risperidone at endpoint was 1.16 mg/day (SD=0.57) (dose range=0.006–0.092 mg/kg per day; mean=0.037 mg/kg per day). In four cases, deviations from the protocol occurred and study participants received more than the upper dose limit of 0.06 mg/kg per day. The existing database does not make it possible to discern whether these deviations were due to parental noncompliance or physician error. In the risperidone group, 29.1% of subjects received doses less than 1 mg/day, 47.3% received doses between 1 and 1.5 mg/day, and 23.6% received more than 1.5 mg/day. The mean duration of treatment during the double-blind period was 36.1 days (SD=12.5) in the risperidone group and 35.6 days (SD=10.3) in the placebo group.

Efficacy Measures

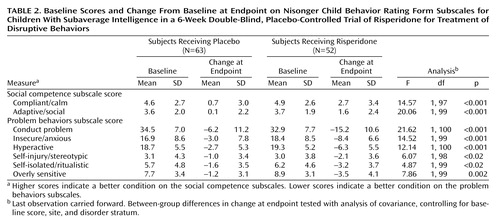

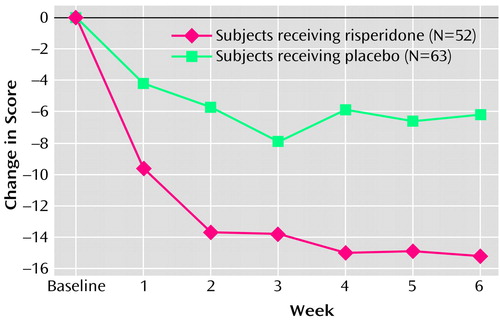

The risperidone group had a significantly greater decrease in the Nisonger Child Behavior Rating Form conduct problem subscale score than did the placebo group at endpoint (change in score of –15.2 and –6.2, respectively) (Table 2, Figure 1). A statistically significant difference between the mean change for the placebo (–4.2) and risperidone (–9.6) groups occurred as early as week 1 (F=7.65, df=1, 97, p=0.007, ANCOVA controlling for baseline score, site and disorder stratum) and was maintained throughout the 6-week study (week 2: –5.7 and –13.7, respectively [F=17.55, df=1, 93, p≤0.01]; week 3: –7.9 and –13.7, respectively [F=7.06, df=1, 87, p=0.009]; week 4: –5.9 and –15.0, respectively [F=10.47, df=1, 78, p=0.002]; week 5: –6.6 and –15.1, respectively [F=7.11, df=1, 69, p=0.01]; week 6: –6.2 and –15.2, respectively [F=9.42, df=1, 63, p=0.003]) (Figure 1).

Compared with placebo, risperidone was associated with significantly greater improvement on all other subscales of the Nisonger Child Behavior Rating Form at endpoint (Table 2). In the risperidone group, prosocial behaviors increased (indicated by higher scores on the compliant/calm and adaptive/social subscales) and problem behaviors decreased (indicated by lower scores on the insecure/anxious, hyperactive, self-injury/stereotypic, self-isolated/ritualistic, and overly sensitive subscales).

The risperidone group had significantly greater improvement than the placebo group at endpoint on the irritability, lethargy/social withdrawal, and hyperactivity/noncompliance subscales of the Aberrant Behavior Checklist and on the Behavior Problems Inventory aggressive/destructive subscale (Table 3).

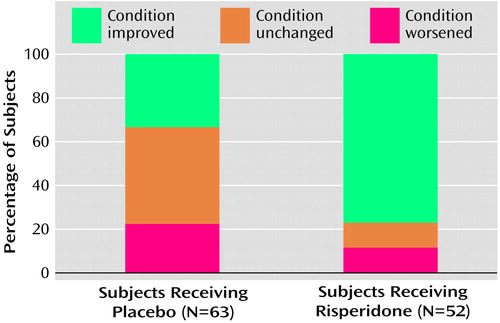

Improvement as measured by the CGI change score was significantly greater in the risperidone group than in the placebo group at endpoint (χ2=20.7, df=1, p<0.001, Van Elteren test controlling for site and disorder stratum) (Figure 2). At endpoint, 40 patients (76.9%) in the risperidone group and 21 (33.4%) in the placebo group were rated as “improved.” This difference occurred as early as week 1 and was maintained throughout the study (χ2>4.3, df=1, p<0.05, from week 1, Van Elteren test controlling for site and disorder stratum). At endpoint, five (7.9%) of 63 subjects in the placebo group and 28 (53.8%) of the 52 subjects with post-baseline data in the risperidone group were rated as “much to very much improved” (χ2=20.74, df=1, p<0.001).

The mean visual analogue scale score (maximum possible score=100) for the most troublesome symptom in the risperidone group improved by a mean of 38.6 (SD=28.7) at endpoint from a baseline mean value of 83.7 (SD=18.7), compared with a mean improvement of only 15.9 (SD=32.1) at endpoint in the placebo group from a baseline value of mean=82.8 (SD=17.4) (Table 3). Significant improvement in the visual analogue scale score for the most troublesome symptom was observed as early as week 1 and was maintained throughout the treatment phase (week 1: F=5.20, df=1, 97, p<0.05; week 2: F=14.35, df=1, 94, p<0.01; week 3: F=7.12, df=1, 88, p<0.01; week 4: F=16.10, df=1, 78, p<0.01; week 5: F=7.45, df=1, 69, p<0.01; week 6: F=5.18, df=1, 66, p<0.05).

The higher rate of somnolence/sedation in the risperidone group (N=28) than in the placebo group (N=6) prompted a subanalysis to assess the influence of somnolence on the efficacy results. Among subjects for whom somnolence/sedation was not reported as an adverse event, those who received risperidone showed significantly greater improvement than those who received placebo in the conduct problem subscale of the Nisonger Child Behavior Rating Form as well as on all other subscales of the Nisonger Child Behavior Rating Form at endpoint (adaptive/social: F=18.6, df=1, 68, p<0.001; conduct problem: F=22.9, df=1, 68, p<0.001; hyperactive: F=12.08, df=1, 68, p<0.001; insecure/anxious: F=11.44, df=1, 68, p<0.001; overly sensitive: F=14.85, df=1, 68, p<0.001; self-injury/stereotypic: F=5.01, df=1, 66, p<0.03; self-isolated/ritualistic: F=5.33, df=1, 67, p<0.03). Moreover, patients without somnolence who received risperidone had significantly greater improvement than those receiving placebo on the total Behavior Problems Inventory score (F=10.78, df=1, 67, p=0.001) and on the visual analogue scale of the most troublesome symptom (F=12.92, df=1, 68, p<0.001) at endpoint in analyses controlling for site, baseline, and disorder stratum. These results indicated that the effects of risperidone were not attributable to sedation.

Safety

Adverse events were reported in 54 patients (98%) in the risperidone group and 44 (70%) in the placebo group. The most common adverse events for the placebo and risperidone groups, respectively, were as follows: 1) somnolence: 10% and 51%, 2) headache: 14% and 29%, 3) vomiting: 6% and 20%, 4) dyspepsia: 6% and 15%, 5) weight increase: 2% and 15%, 6) elevated serum prolactin: 2% and 13%, 7) increased appetite: 6% and 11%, and 8) rhinitis: 5% and 11%. Somnolence was generally mild and transient and did not lead to discontinuation except in two subjects. Most adverse events were mild to moderate, and no serious adverse events were reported.

There were no significant between-group differences in the severity of extrapyramidal symptoms as measured by Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale scores at endpoint (Table 4). Two patients in the risperidone group reported extrapyramidal symptoms as an adverse event. No subjects required medication to treat extrapyramidal symptoms.

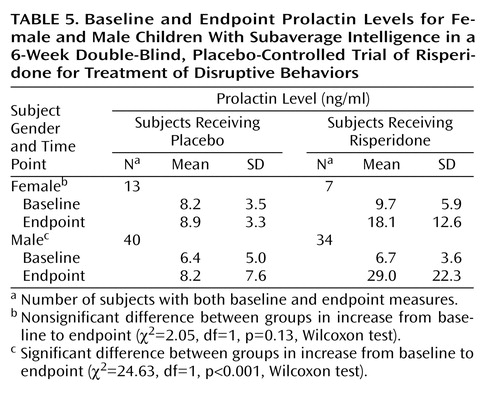

There were no clinically significant between-group differences in mean changes in laboratory values at endpoint, except for prolactin level. For boys, there was a greater increase in mean prolactin level in the risperidone group than in the placebo group at endpoint (Table 5); the difference in increase in mean prolactin level was not statistically significant for girls. The prolactin increase was observed on the laboratory tests and was not associated with clinical symptoms. Gynecomastia, amenorrhea, or other prolactin-related adverse events were not reported.

Risperidone-treated patients had a mean weight increase of 2.2 kg (4.8 lb) (SD=1.8 kg), and patients receiving placebo had an increase of 0.9 kg (2.0 lb) (SD=1.5 kg) (F=12.92, df=1, 96, p<0.001, ANOVA with factors for site and disorder). A temporary 11-bpm increase in heart rate occurred during the first 2 weeks of treatment in the risperidone group, compared with the placebo group (week 1: F=4.62, df=1, 95, p<0.04, week 2: F=7.62, df=1, 95, p=0.006). Thereafter heart rates in the risperidone group were normal, and no significant differences occurred for the remainder of the study. No QTc abnormalities occurred during risperidone treatment.

At endpoint, the mean visual analogue scale score for sedation (higher scores are indicative of sedation) was –2.02 for placebo and 5.90 for risperidone (F=7.43, df=1, 99, p=0.008, ANCOVA with factors for site, baseline, and disorder). Changes were small; there were no drug-related changes on the cognitive tests.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that risperidone was significantly superior to placebo for reducing severe problem behaviors, including aggressive, insecure/anxious, hyperactive, self-injurious, and stereotypic behaviors in children with subaverage IQ. A variety of instruments, including the Nisonger Child Behavior Rating Form, Aberrant Behavior Checklist, Behavior Problems Inventory, and CGI change score, all demonstrated that risperidone provided significantly greater symptom improvement than placebo in this subject group; moreover, the treatment was well tolerated throughout the study.

The subjects were quite symptomatic at study entry, with a mean baseline score of approximately 34 on the conduct problem subscale of the Nisonger Child Behavior Rating Form, which corresponds with the 90th percentile for the normative sample of developmentally disabled children described by Tassé et al. (43). Significant impairment was confirmed by a baseline Vineland Adaptive Behavior score of approximately 55. This score is nearly a full standard deviation below the subjects’ mean IQ of 68, suggesting that their conduct problems were contributing to other significant difficulties in basic survival skills needed to succeed in everyday life.

Although the total number of patients entering this study was not particularly large, the magnitude of effect was quite pronounced, and the medication effect was striking. However, in a new therapeutic area in which no adequate placebo-controlled studies have been conducted, it is difficult to be certain of the clinical significance of the observed results. It may be helpful to examine the efficacy data to evaluate the clinical importance of our findings.

To assess the clinical significance of this differential score change, first the findings of Tassé et al. (43) may be considered. Their investigation established norms from the Nisonger Child Behavior Rating Form among subjects 10–16 years old with developmental disabilities referred to a university-affiliated clinic. The mean conduct problem subscale score was 20 (SD=14); the 70th percentile criterion was 24 points. Thus, the 9-point difference in improvement between risperidone and placebo constituted more than 64% of a standard deviation of change. This magnitude of change would bring a subject who is symptomatic at the 70th percentile criterion to a below-average score (roughly the 50th percentile of all subjects). We consider this change clinically relevant. Second, the investigators’ CGI scores also address clinical significance. Defining a responder as a subject with an endpoint rating of very much or much improved on the CGI improvement scale, the percentage of responders was 53.8% in the risperidone group and 7.9% in the placebo group, a significant difference. Third, the percentage of discontinuations for lack of efficacy from a controlled study is a clinically relevant assessment of efficacy that is independent of any protocol definition. In this study, the rate of discontinuations for insufficient response was substantially higher in the placebo group (N=15, 24%) than in the risperidone group (N=4, 8%). When these three measures of clinical effectiveness are considered, the study shows that the improvements associated with risperidone were of considerable clinical significance.

Another important clinical finding was the rapid onset of therapeutic effect. Significant improvements in behavior occurred as early as 1 week after starting risperidone. This onset of effect is faster than that of either lithium or carbamazepine (but not the stimulants) used in treatment of conduct disorder, for which 2–6 weeks may be required for full therapeutic effect (1). Furthermore, there is no requirement to monitor blood levels with risperidone. The narrow therapeutic index of lithium requires regular monitoring of serum lithium levels to avoid life-threatening toxicity. Thus, risperidone appears to have other clinical advantages over alternative psychotropic agents.

Although sedation was common in this study, the positive effects of risperidone on behavior measures were shown to be independent of the sedative effects. In most cases, sedation was mild and transient and did not lead to discontinuation. This is important, since it has previously been postulated that the efficacy of antipsychotics for aggressive behavior may be attributable to their sedative effect (1). It is possible that some of risperidone’s effectiveness may have been due to ataraxis (emotional calmness), but, as pointed out later, medication appeared to exert other actions as well. Finally, although risperidone caused somnolence in some children, this change was beneficial in some participants. An unknown but sizable proportion of the children entered the study with significant problems sleeping, and (anecdotally) the drug seemed to enhance sleep hygiene in some.

The positive effects of risperidone occurred at a relatively low average dosage of 1.16 mg/day at the end of the study. The dose was administered using a once-daily regimen for most subjects, which may help promote treatment adherence. Only three patients in this study were considered to be noncompliant.

To our knowledge, this study is only the second large, randomized, placebo-controlled trial to examine the use of an antipsychotic in the treatment of pediatric patients with behavioral disorders. Campbell et al. (1) performed a placebo-controlled study with haloperidol and lithium. In a smaller double-blind, placebo-controlled study Findling et al. (15) also observed that risperidone was effective for decreasing aggressive behavior in children with conduct disorder and normal IQ. The findings of this study are also consistent with the findings of Van Bellinghen and De Troch (16) and Buitelaar et al. (17) and with those of multiple open-label studies and case reports describing the use of risperidone in patients with behavior disorders (18–37).

Risperidone was well tolerated throughout the 6-week study. No unexpected adverse events occurred. Although extrapyramidal symptoms are a major concern with the use of many antipsychotics, they were uncommon in this study (Table 4). Also, no ECG abnormalities occurred. Although it has been suggested that the use of lithium or haloperidol for the treatment of conduct disorder may impair cognition (54), no evidence of cognitive impairment was seen in this study. Weight gain may cause concern with the use of most antipsychotics; however, reports suggest that weight gain with risperidone is less than that with other atypical antipsychotics (e.g., clozapine, olanzapine) (55). In this study, a weight gain of 2.2 kg (4.8 lb) occurred with risperidone, compared with 0.9 kg (2 lb) for placebo-treated subjects. Prolactin levels were elevated, but were not associated with clinical sequelae. We conducted a 1-year open-label follow-up to this study and found that prolactin levels declined to near-normal levels within 12 months (unpublished 2001 findings, R.L. Findling et al.). However, the long-term implications of prolactin elevation in children is not known at this time, so clinicians may wish to reconsider use of this or other antipsychotics if prolactin levels remain elevated for significant time intervals.

This 6-week study demonstrated that risperidone was superior to placebo for controlling aggressive, insecure/anxious, hyperactive, self-injurious, and stereotypic behaviors in children with mild or moderate intellectual limitations or IQ in the low–normal range. The 1-year follow-up data (unpublished 2001 findings, R.L. Findling et al.) confirmed the durability of efficacy and the safety of long-term risperidone administration in these patients. Furthermore, the parents’ ratings on the Nisonger Child Behavior Rating Form suggested improvements in social competence with risperidone. This observation is worthy of further research. If confirmed as a true drug effect, this finding may suggest that risperidone actually enhanced prosocial adaptive behavior and reduced disruptive symptoms. Future studies would expand our range of knowledge by addressing effects of risperidone in patients with other behavioral disorders and in patients with behavior disturbances and intellectual functioning outside the range of the subjects assessed here (i.e., in those with normal IQ or severe intellectual disability).

In conclusion, risperidone produced both statistically and clinically significant improvements in these children. The main common characteristic of all subjects in this study was a repetitive and persistent pattern of socially dysfunctional, aggressive, or defiant behavior that was sufficiently severe that the investigators decided that pharmacotherapy was warranted. Like all antipsychotics, risperidone should be used cautiously, especially in children, whose brains are still developing. We recommend that clinicians prescribing risperidone (or any antipsychotic agent) obtain baseline measures of height, weight, and possibly motor movements and that these measures be repeated at appropriate intervals. Although we observed no sexual adverse events in this trial, we also recommend inquiry and, where appropriate, examination for possible prolactin-related sexual side effects.

Acknowledgments

The other authors in the Risperidone Disruptive Behavior Study Group were Randi Hagerman, M.D., Sacramento, Calif.; Benjamin Handen, Ph.D., Pittsburgh; Jessica Hellings, M.D., Kansas City, Kans.; Michael Lesem, M.D., Bellaire, Tex.; Jörg Pahl, M.D., Oklahoma City; Deborah A. Pearson, Ph.D., Houston; Michael Rieser, M.D., Lexington, Kent.; Nirbhay N. Singh, Ph.D., Richmond, Va.; and James Swanson, Ph.D., Irvine, Calif.

|

|

|

|

|

Received Aug. 1, 2001; revision received March 20, 2002; accepted April 3, 2002. From the Nisonger Center UAP, Ohio State University; the Janssen Research Foundation, Beerse, Belgium, and Titusville, N.J.; and the Departments of Psychiatry and Pediatrics, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland. Address reprint requests to Dr. Aman, Nisonger Center UAP, Ohio State University, 1581 Dodd Dr., Columbus, OH 43210-1257; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by the Janssen Research Foundation.

Figure 1. Mean Change in Score on the Conduct Problem Subscale of the Nisonger Child Behavior Rating Form for Children With Subaverage Intelligence in a 6-Week Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial of Risperidone for Treatment of Disruptive Behaviorsa

aLast observation carried forward. Significant differences between groups at weeks 1–6.

Figure 2. Clinical Global Impression of Change in Subjects’ Condition at Endpoint for Children With Subaverage Intelligence in a 6-Week Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial of Risperidone for Treatment of Disruptive Behaviorsa

aLast observation carried forward.

1. Campbell M, Gonzalez NM, Silva RR: The pharmacological treatment of conduct disorders and rage outbursts. Psychiatr Clin North Am 1992; 15:69-85Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Scott S: Aggressive behaviour in childhood. Br Med J 1998; 316:202-206Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Steiner H: American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Practice parameters for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with conduct disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997; 36(suppl 10):122S-139SGoogle Scholar

4. Campbell M, Malone RP: Mental retardation and psychiatric disorders. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1991; 42:374-379Abstract, Google Scholar

5. Lovell RW, Reiss AL: Dual diagnoses: psychiatric disorders in developmental disabilities. Pediatr Clin North Am 1993; 40:579-592Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Dosen A: Diagnosis and treatment of psychiatric and behavioural disorders in mentally retarded individuals: the state of the art. J Intellect Disabil Res 1993; 37(suppl 1):1-7Google Scholar

7. Moss S, Emerson E, Bouras N, Holland A: Mental disorders and problematic behaviours in people with intellectual disability: future directions for research. J Intellect Disabil Res 1997; 41:440-447Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Schaal DW, Hackenberg T: Toward a functional analysis of drug treatment for behavior problems of people with developmental disabilities. Am J Ment Retard 1994; 99:123-140Medline, Google Scholar

9. Santosh PJ, Baird G: Psychopharmacotherapy in children and adults with intellectual disability. Lancet 1999; 354:233-242Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Lavin MR, Rifkin A: Diagnosis and pharmacotherapy of conduct disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 1993; 17:875-885Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Werry JS: Severe conduct disorder—some key issues. Can J Psychiatry 1997; 42:577-583Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Moretti MM, Emmrys C, Grizenko N, Holland R, Moore K, Shamsie J, Hamilton H: The treatment of conduct disorder: perspectives from across Canada. Can J Psychiatry 1997; 42:637-648Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Brestan EV, Eyberg SM: Effective psychosocial treatments of conduct-disordered children and adolescents: 29 years, 82 studies, and 5,272 kids. J Clin Child Psychol 1998; 27:180-189Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Baumeister AA, Sevin JA, King B: Neuroleptics, in Psychotropic Medications and Developmental Disabilities: The International Consensus Handbook. Edited by Reiss S, Aman MG. Columbus, Ohio State University, Nisonger Center, 1998, pp 133-150Google Scholar

15. Findling RL, McNamara NK, Branicky LA, Schluchter MD, Lemon E, Blumer JL: A double-blind pilot study of risperidone in the treatment of conduct disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2000; 39:509-516Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Van Bellinghen M, De Troch C: Risperidone in the treatment of behavioral disturbances in children and adolescents with borderline intellectual functioning: a double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot trial. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2001; 11:5-13Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Buitelaar JK, van der Gaag, RJ, Cohen-Kettenis P, Melman CTM: A randomized controlled trial of risperidone in the treatment of aggression in hospitalized adolescents with subaverage cognitive abilities. J Clin Psychiatry 2001; 62:239-248Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Kewley GD: Risperidone in comorbid ADHD and ODD/CD. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1999; 38:1327-1328Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Hardan A, Johnson K, Johnson C, Hrecznyj B: Case study: risperidone treatment of children and adolescents with developmental disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1996; 35:1551-1556Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Fras I, Major LF: Clinical experience with risperidone (letter). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1995; 34:833Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Carroll NB, Boehm KE, Strickland RT: Chorea and tardive dyskinesia in a patient taking risperidone. J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 60:485-487Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Kleinsasser BJ, Misra LK, Bhatara VS, Sanchez JD: Risperidone in the treatment of choreiform movements and aggressiveness in a child with “PANDAS.” SD J Med 1999; 52:345-347Google Scholar

23. Schreier HA: Risperidone for young children with mood disorders and aggressive behavior. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 1998; 8:49-59Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Simeon JG, Carrey NJ, Wiggins DM, Milin RP, Hosenbocus SN: Risperidone effects in treatment-resistant adolescents: preliminary case reports. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 1995; 5:69-79Crossref, Google Scholar

25. Posey DJ, Walsh KH, Wilson GA, McDougle CJ: Risperidone in the treatment of two very young children with autism. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 1999; 9:273-276Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Horrigan JP, Sikich L: Diet and the atypical neuroleptics. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1998; 37:1126-1127Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Frischauf E: Drug therapy in autism (letter). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997; 36:577Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. McDougle CJ, Holmes JP, Bronson MR, Anderson GM, Volkmar FR, Price LH, Cohen DJ: Risperidone treatment of children and adolescents with pervasive developmental disorders: a prospective, open-label study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997; 36:683-693Google Scholar

29. Demb H: Risperidone in young children with pervasive developmental disorders and other developmental disabilities. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 1996; 6:79-80Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Fisman S, Steele M, Short J, Byrne T, Lavallee C: Case study: anorexia nervosa and autistic disorder in an adolescent girl. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1996; 35:937-940Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Fisman S, Steele M: Use of risperidone in pervasive development disorders: a case series. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 1996; 6:177-190Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Fitzgerald KD, Stewart CM, Tawile V, Rosenberg DR: Risperidone augmentation of serotonin reuptake inhibitor treatment of pediatric obsessive compulsive disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 1999; 9:115-123Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Frazier JA, Meyer MC, Biederman J, Wozniak J, Wilens TE, Spencer TJ, Kim GS, Shapiro S: Risperidone treatment for juvenile bipolar disorder: a retrospective chart review. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1999; 38:960-965Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Findling RL, Maxwell K, Wiznitzer M: An open clinical trial of risperidone monotherapy in young children with autistic disorder. Psychopharmacol Bull 1997; 33:155-159Medline, Google Scholar

35. Vanden Borre R, Vermote R, Buttiens M, Thiry P, Dierick G, Geutjens J, Sieben G, Heylen S: Risperidone as add-on therapy in behavioural disturbances in mental retardation: a double-blind placebo-controlled cross-over study. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1993; 87:167-171Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Nicolson R, Awad G, Sloman L: An open trial of risperidone in young autistic children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1998; 37:372-376Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Horrigan JP, Barnhill LJ: Risperidone and explosive aggressive autism. J Autism Dev Disord 1997; 27:313-323Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Simon EW, Blubaugh KM, Pippidis M: Substituting traditional antipsychotics with risperidone for individuals with mental retardation. Ment Retard 1996; 34:359-366Medline, Google Scholar

39. Khan BU: Brief report: risperidone for severely disturbed behavior and tardive dyskinesia in developmentally disabled adults. J Autism Dev Disord 1997; 27:479-489Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. Cohen SA, Ihrig K, Lott RS, Kerrick JM: Risperidone for aggression and self-injurious behavior in adults with mental retardation. J Autism Dev Disord 1998; 28:229-233Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41. Lott RS, Kerrick JM, Cohen SA: Clinical and economic aspects of risperidone treatment in adults with mental retardation and behavioral disturbance. Psychopharmacol Bull 1996; 32:721-729Medline, Google Scholar

42. Dartnall NA, Holmes JP, Morgan SN, McDougle CJ: Brief report: two-year control of behavioral symptoms with risperidone in two profoundly retarded adults with autism. J Autism Dev Disord 1999; 29:87-91Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

43. Tassé MJ, Aman MG, Hammer D, Rojahn J: The Nisonger Child Behavior Rating Form: age and gender effect and norms. Res Dev Disabil 1996; 17:59-75Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

44. Aman MG, Tassé MJ, Rojahn J, Hammer D: The Nisonger CBRF: a child behavior rating form for children with developmental disabilities. Res Dev Disabil 1996; 17:41-57Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

45. Sparrow SS, Balla DA, Cicchetti DV: Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales. Circles Pines, Minn, American Guidance Service, 1984Google Scholar

46. Aman MG, Singh NN, Stewart AW, Field CJ: The Aberrant Behavior Checklist: a behavior rating scale for the assessment of treatment effects. Am J Ment Defic 1985; 89:485-491Medline, Google Scholar

47. Rojahn J, Matson JL, Lot D, Esbensen AJ, Smalls Y: The Behavior Problems Inventory: an instrument for the assessment of self-injury, stereotyped behavior, and aggression/destruction in individuals with developmental disabilities. J Autism Dev Disord 2001; 31:577-588Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

48. Gadow KD, Sprafkin J: Child Symptom Inventories Manual. Stony Brook, NY, Checkmate Plus, 1994Google Scholar

49. Wechsler D: Manual for the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, Third Edition. San Antonio, Tex, Psychological Corp, 1991Google Scholar

50. Aman MG: Applications of computerized cognitive-motor measures to the assessment of psychoactive drugs, in Assessing Cognitive Function in Epilepsy. Edited by Dodson WE, Kinsbourne M, Hiltbrunner B. New York, Demos, 1991, pp 69-96Google Scholar

51. Delis DC, Kramer JH, Kaplan E, Ober BA: California Verbal Learning Test, Children’s Version, Manual. Orlando, Fla, Psychological Corp/Harcourt, Brace, 1998Google Scholar

52. Chouinard G, Ross-Chouinard A, Annable L, Jones B: Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale (abstract). Can J Neurol Sci 1980; 7:233Google Scholar

53. Agresti A: Categorical Data Analysis. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1990Google Scholar

54. Platt JE, Campbell M, Grega DM, Green WH: Cognitive effects of haloperidol and lithium in aggressive conduct-disorder children. Psychopharmacol Bull 1984; 20:93-97Medline, Google Scholar

55. Taylor DM, McAskill R: Atypical antipsychotics and weight gain—a systematic review. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2000; 101:416-432Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar